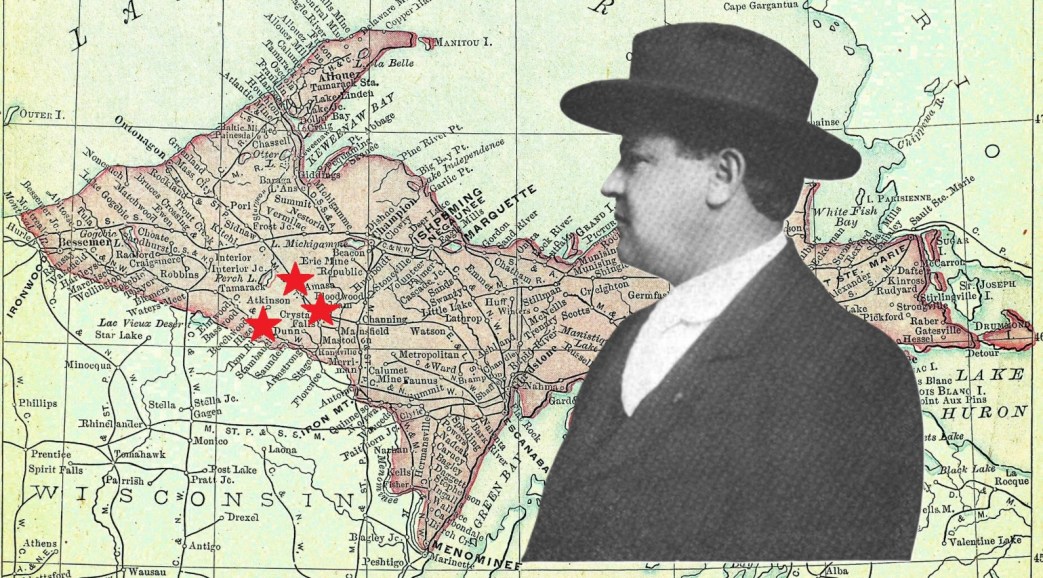

Haywood had a power. Here he breaks through in Michigan’s western Upper Peninsula towns of Iron River, Amasa, and Crystal Falls, becoming the first English-speaking Socialist to have public meetings in the mining villages; all of which would develop into Socialist and Communist strongholds over the next two generations.

‘Haywood’s Work Brings Results’ from The New York Daily Call. Vol. 3 No. 166. June 13, 1910.

Breaks Through Mine Owners’ Exclusion Wall for Agitators in Michigan. Good Werk for Socialism.

AMASA, Mich. June 11. The mine owner’s exclusion wall in Michigan, built for the sole purpose of preventing labor and Socialist organizers from entering mining and mill towns has at last been penetrated and torn down.

William D. Haywood, acting on the request of local Western Federation and Socialist organizations, entered the thus far forbidden fields, and in spite of plots and threats on the part of mine owners and subservient authorities, held rousing meetings in the following forbidden mining towns: Crystal Falls, Amasa, Iron River.

In Crystal Falls the cockroach businessmen and politicians, goaded on by the all-powerful mine owners, threatened to run Haywood out before he had time to draw a breath. This, in view of the fact that Stirton, Kalu, Corpi and Bertelli, organizers, had been run out of the town, and threatened with hanging if they came back, looked pretty serious, but Haywood, accompanied by Robert Dvorak, entered the town where Frank Altonen, organizer for the Western Federation of Miners, had arranged for a meeting in the Opera House, and were there greeted by almost the whole town.

Every person, including the mayor, marshal, and nearly all of the town police, and some of the mine owners, had paid admission to the hall to hear what the terrible Bill Haywood had to say. They heard a burning indictment of themselves and their tactics, and saw almost every person applaud and buy pamphlets on Socialism.

Amasa is a little mining and hunting town of about 2,000 people. Here, again, the labor and Socialist organizer, is an undesirable person. Deliberate preparations were made to spoil the meeting. The mine owners did their very best to breed a sentiment against Haywood among the people of the town.

A plan was afoot to run the fire engine out to the St. Paul depot, where the meeting was to be held in the open air, and douse the speaker with a stream of water. The plotters, however, figured without the people. As a result the engine was left in the fire house, the marshal was warned, too, against interfering with Haywood in any unfair manner.

In the evening almost the entire town turned out, and sat in the prairies near the depot until 10 o’clock listening first to Haywood and then to Frank Altonen, who spoke to his countrymen in Finnish.

During the meeting, which was interrupted with applause for the Socialist and Industrial program with jeers for the mine owners, who were present, the enthusiasm among the people of Amasa, who had never before heard an American Socialist speaker, was so high that $14.60 worth of literature was sold that evening.

A deep and well-planned conspiracy greeted Haywood in Iron River, another mining town of about 3,000 people. Here the mine owners discussed Haywood in the council, and by a vote of 4 to 2 decided against allowing the miner to speak in the town hall, which had already been paid for.

The aldermen took the lease away from the man who had rented the Socialists the town hall, and asked the Young Men’s Club to give a dance there on the night after the meeting. The young men claimed they could not let Haywood speak in the hall because they would have to decorate that night. Haywood agreed to hire two decorators, but arguments brough no result.

Investigation later showed that the council had held a hot session on hearing of Haywood’s intention to speak in the town hall. Mayor Quisy and Hartley, an alderman and tailor in the town, stood for allowing the meeting. The meeting might have been allowed had not Woodwarth, the alderman and the mine owner, called the mayor a fool and demanded that the meeting be not allowed.

Woodwarth is a political power in the town and the hall was denied the Socialists. Oberg, a retail gents’ furnisher, showed his great friendship for the workingmen in Iron River who bring him money for his wares by obstinately refusing to compromise in any way with Haywood regarding the meeting. He is the leader of the Young Men’s Club, and had authority to do as he pleased.

The result of the plot was that the mayor was cornered by Haywood and he agreed to allow a street meeting, providing no attempt was made to incite the citizens to murder or incendiary acts.

The street was jammed with citizen miners who were indignant over the treatment accorded Haywood by the council. The Socialist local strengthened and many new members were secured to the Western Federation of Miners.

The meetings held in Amasa and Iron River are the first ones ever held there in English, and are the wedge to a complete series of others. Socialist locals now have been established or strengthened in in each of them and literature scattered–all of it being purchased by the people in the audience.

Haywood makes it a point to give every boy in the audience a booklet on Socialism, and it is a grand sight to see the boys listen attentively as he tells them in their boys’ tongue what Socialism stands for.

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1910/100615-newyorkcall-v03n166.pdf