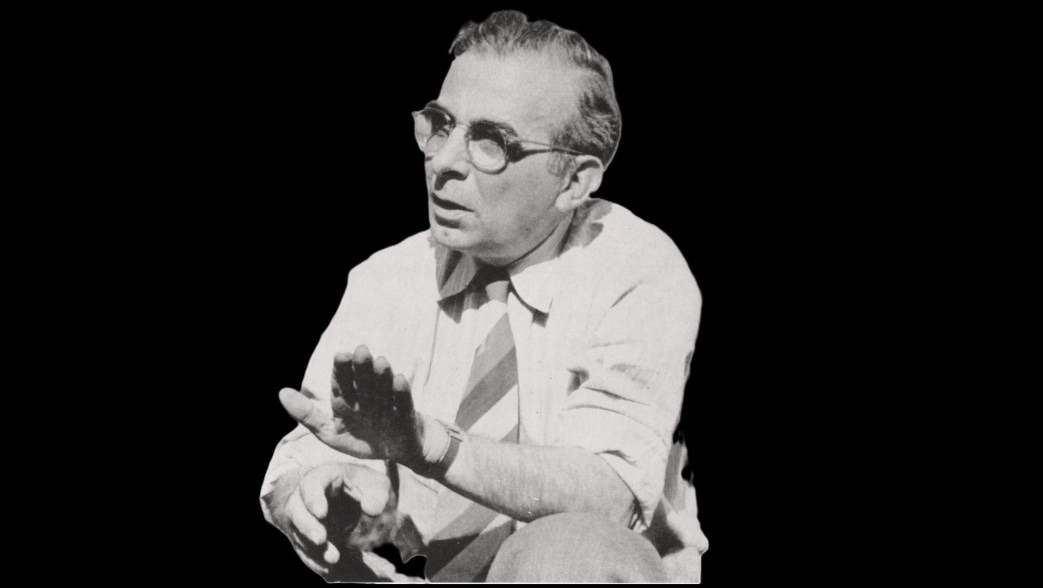

An important piece from U.S. Communism”s founding figure. Written a few months after the beginning of the First World War and collapse of the Second International, Louis C. Fraina firmly and cogently voices an anti-war, internationalist critique of capitalism and socialism, becoming a leader for the new International that would be formed five years later.

‘The Future of Socialism’ by Louis C. Fraina from New Review. Vol 3. No. 1. January, 1915.

There was no collapse of Socialism in Europe. It was a collapse of Socialist illusions—a logical and necessary collapse. Socialism remains intact, to take thought, clarify its theory and tactic, and recommence its journey toward its goal. The only ominous thing about the future of Socialism is the blind stupidity of those who refuse to recognize this collapse and its reasons, and who mumble the same phrases that in a tragic crisis proved utterly illusory.

Socialists may well vision progress towards Socialism as a consequence of the Great War. But if that progress is to be achieved, the Socialist movement must adapt itself to transformed conditions and new requirements. This is what makes the attitude of many Socialists alarming. Instead of courageously facing the future they turn to the past. It shows lack of intelligence and adaptability, energy and character. Why insist on the guilt of Capitalism? That doesn’t absolve Socialism. Why prate of the International? The “International” was dominantly nationalistic, and has collapsed. Why insist on the supreme utility of parliamentary action when parliamentary action showed itself impotent in the European crisis? Why ascribe the German Socialist collapse to the movement being “non-revolutionary” and run by “politicians”? We must look for the social forces which produced these facts. Above all, why speak of “revolution” in the glib fashion customary in the past? After the war new conceptions of reform and revolution must be developed, and new conditions of revolutionary action prevail. Let us cease indulging in the illusions and phrases which frequently pass muster as Socialist thought and Socialist propaganda.

REVOLUTIONARY SOCIAL TRANSFORMATIONS

Incidentally, another discouraging thing is the kind of arguments generally used to show how the war is making for Socialism. One of these arguments runs this way: The warring governments are making “ciphers” of the capitalists; the capitalist “is not even consulted as to the use to be made of ‘his’ property”; the privately-owned railroads of England are being operated “exactly the way the military authorities think necessary, without the least regard for the ‘owners’,” and this proves “the collapse of the profit system”! But in what way does all that make for Socialism? Are military dictatorships and Socialism synonymous? Property has always been at the arbitrary disposal of governments in time of war; Benjamin Franklin expressed the matter tersely: “Property is the creature of society, and society is entitled to the last farthing whenever society needs it.” That is not Socialism. The actions of the warring governments in Europe are at the most giving an impetus to State Capitalism and State Socialism. The war is not making for Socialism because governments are trampling on the “rights of property”; nor because Guesde and Vandervelde are members of bourgeois cabinets; nor because people are going to revolt against the governments “responsible” for the war and its horrors. For the hope of progress toward Socialism one must look deeper—deep into the social process itself. The Great War is making for Socialism in the sense that its consequences mean a new and better basis for the Socialist struggle against Capitalism.

The war has unloosed tremendous forces which are bound to revolutionize bourgeois society. We shall see a new era of Capitalist development, of industrial expansion—not “the collapse of the profit system”; the rise of a new and mightier Capitalism; and this should mean Socialist progress; Marx repeatedly called upon Socialists to assist the political and economic development of Capitalism. Beaten or victorious, Germany will be transformed: industrial Bavaria ascendant and not Junker Prussia; profound political transformations imminent, if not actually achieved, at the close of the war,—on the march to political democracy and non-feudal Capitalism. In all probability, France will emerge with State Socialism dominant in its government; the restoration of Alsace-Lorraine with its large coal and iron resources would mean a mighty impetus to industrial development. An industrialized Russia, with Capitalism making gigantic progress, will achieve what the social-revolutionary martyrs did not—just as the Napoleonic regime, and not Robespierre and Marat, accomplished the fundamental work of the Revolution. With this clearing out of pre-capitalistic conditions, and the emergence of a higher and more definite Capitalism in Europe and other sections of the world, class groupings and class antagonisms become simplified and intensified; and clarity of social divisions makes easier the task of revolutionary Socialism. Socialism is the expression of definite social conditions, and does not develop equally under any and all conditions. All of which means a clear-cut revolutionary movement and Socialist progress, providing Socialists do not assume fatalistically that the process will go on beautifully of itself to the desired end.

The war has shaken, should shake, us out of the rut. Social development alone is not going to do our work. Our own ineptitude may undo things. Our own actions are the determining factor in the future of Socialism. We must become more fearless in action and in thought—particularly in self-directed thought. We must use Socialist theory to analyze our own actions as well as those of our foes. The Socialist movement must become humanized, concern itself more with human emotions and the spiritual reality of life. Theory is not all. Socialism must identify itself with psychology. A thorough reconsideration of Socialist principles is the order of the day. Marx should be translated into terms of modern social conditions. On the basis of Marx, Socialist propaganda has erected an unreal, metaphysical structure of theory and tactics which must be destroyed,1 and it matters not whether the structure is “revolutionary” or “revisionist.” Marx gave us the general principles to be used intelligently, progressively.

SOCIALIST ILLUSIONS

In spite of our scientific claims we are not sufficiently scientific in our methods of thought. Instead of considering the social process as a whole, as Marx did, we tend to emphasize particular, isolated facts,2 to not consider in our theoretical and tactical conclusions all the facts of the social process; and generally to square facts with theory where we do not ignore the facts entirely. This produces a multiplicity of illusions, confusions and compromises.

A pervasive Socialist illusion expresses itself in the concept that proletarian interests are now determinant in social progress. They are not. Marx foresaw that these interests would become determinant. His disciples, however, proceeded to emphasize the determinant character of proletarian interests, and to deny other social groups and economic interests their due importance. But these groups and interests asserted themselves. Instead of recognizing their social value and drawing an emphatic distinction, Socialists practically and often theoretically identified these non-proletarian interests with the interests of the proletariat itself. Being the more determinant, these non-proletarian interests assumed dominance in the Socialist movement.

That was precisely the colossal error of the German Social-Democracy. Fundamentally, the Social-Democracy has been a bourgeois Republican movement. The reaction in 1848 crushed the revolutionary middle-class in Germany; national unity was achieved with the feudal Junkers’ power intact, and bourgeois democracy still a thing of the future. Instead of concerning itself exclusively with the interests of the proletariat, the Social-Democracy assumed the task of finishing the work left undone by the bourgeois revolution,—a necessary task in the social process, but one which should not have been identified with Socialism. The task of bourgeois revolution itself was hampered by this combination of Socialism with bourgeois reform. Many people who desired reform were frightened away by the Socialist phrases; a clear-cut bourgeois Republican movement would have accomplished the reforms infinitely easier. Socialism was warped in its theoretical and practical activity, denied its own normal development, allied with social groups and interests alien to the proletariat. Within recent years the Social-Democracy has made it clear that its fundamental task was to secure constitutional, Republican government in Germany. Bourgeois Republicans are necessarily and intensely nationalistic; and the Social-Democracy’s support of the Kaiser on a national crisis was a logical result of its bourgeois character, hence nationalistic spirit.

Organized Socialism in all lands has been nationalistic, although not to the extent it has in Germany. The war has proven this conclusively. French and Belgian Socialists justify their going to war almost wholly on nationalistic grounds. Italian Socialists are indulging largely in nationalistic sentiments. British Socialism is intensely nationalistic; while the American Socialist Party’s antiimmigration policy is essentially nationalistic. Organized Socialism has denied Nationalism any utility and necessity while itself strongly nationalistic.

This problem of Nationalism is a crucial one in a discussion of the future of Socialism. The propaganda of Socialism has been based on the assumption that Nationalism is an anachronism—a prejudice of the past—an entirely useless survival in the process of social evolution. The Great War has shaken this assumption; the developments consequent upon the war will smash the assumption completely.

The Great War proves, if it proves anything, that Capitalism is still dominantly national. This shatters another Socialist illusion—the illusion that Capitalism is actually international. Truly, capital roams the world over seeking new fields of endeavor; continually expanding, expansion is a necessity of modern Capitalism. But the impulse behind this expansion is still national. Nations with a highly-developed Capitalism acquire colonies and protectorates to serve national ends. Capitalism, accordingly, is not international economically; much less is Capitalism international in consciousness and aspirations. Undoubtedly the trend is toward internationalized Capitalism; in the meantime, however, national Capitalism being still dominant, Nationalism functions in the social process.

A NEW ERA OF NATIONALIST DEVELOPMENTS

Nationalism was an active cause of the Great War, and one of its larger consequences now visible is a new and mightier series of nationalistic developments. Current recognition of this assumes the form of demanding new national groupings in Europe and the integrity of small states. But the subject is much deeper than that; and its thorough analysis is of vital importance in that Nationalism may modify substantially many phases of Socialist tactics.

The history of Western Europe since the close of the Middle Ages is intimately identified with the history of Nationalism. Ascending Capitalism develops the nation-state, which plays a vital part in the overthrow of feudalism and the establishment of Capitalism. Ascending Capitalism requires freedom of trade within as large a territorial unit as possible, national markets exclusively for national capital, a common system of coinage, weights and measures, a strong central government to protect capital, the development of a sentiment of solidarity among the people of a particular national group. The nation-state develops the illusion of common interests among its people, awakens a sense of solidarity, produces national institutions and national culture, and provides the necessary conditions for Capitalist progress. The mercantile City-State evolves into the Nation-State. The unit of the Nation-State is determined racially, not economically; Capitalism not being powerful enough to make the unit economic, yet sufficiently powerful to arouse and transform the sense of racial solidarity into national unity. The sense of racial solidarity alone does not create national unity—economic interests assume a racial character; in spite of an intense racial consciousness, Turkey never became a real nation because there was no ascending Capitalism in Turkey to provide the necessary economic stimulus. As a consequence Turkey decayed, as Italy decayed when the City-States that were creating a necessity and sentiment for national unity in the thirteenth century waned in power with the shifting of the centre of commercial gravity to northwestern Europe. While an expression of Capitalist development, Nationalism may become an independent factor in the social process, much more dynamic and dominating in a particular situation than its economic basis.

Progress in the Balkans was inconceivable while alien rule impeded freedom of economic, political and cultural activity. National unity in the Balkan states was given impetus by the growing needs of agriculture and commerce; and since national unity was partially achieved through the help of European diplomacy, these economic needs have become larger and more aggressive. The Balkans aspire to a deeper racial, political and economic autonomy—indispensable for the progress of national Capitalism. The assertion of Nationalism meant a struggle of liberty against the feudal tyranny of Turkey and Austria-Hungary. Servia, Bulgaria, Rumania sought to include within their national states territory and people still under foreign domination; this would have meant greater freedom of trade and larger national markets—an impetus to ascending Capitalism. These aspirations were threatened by the military power of Turkey and the policy of economic coercion systematically pursued by Austria-Hungary.3 To nullify this economic coercion, M. Pasitch, the Servian premier, organized in 1904 a customs-union among the Balkan states, which led directly to the Balkan League that crushingly defeated Turkey. This might have prepared the way for the national unity of all the Balkan states (identically as the victory of Prussia in 1870 consummated German unity) had not the intrigues of Austrian diplomacy precipitated the second Balkan War and the League’s collapse. The hope of the Balkan future lies in a Greater Servia and Rumania, and in the federative or national unity of all the Balkan states.

The utility of Nationalism is not restricted to the Balkan stage of social development. Nationalism is necessary, and potently necessary, in Italy and Portugal. Still partly feudal and an agricultural expression, Italy is economically divided against itself, without organic economic and national cohesion; North and South are economically hostile, and each seeks control of the government. This antagonism retards economic growth—much as the antagonism between North and South prior to the American Civil War retarded our own economic growth. Italian unity and the Italian government have not yet taken deep root among the people and institutions of Italy. But there is a strong nationalist movement and nationalist party; the Socialist movement itself is largely democratic and republican, while one section of it is avowedly nationalistic. The task of Nationalism in Italy is the identical task of Nationalism in Spain and Portugal, and even more necessary.

Bearing in mind the historic function of Nationalism, it is immediately obvious that Nationalism has a tremendous role to play in Russa. With Capitalism forging into being, ascending, Nationalism will become a vital factor in cultural and political activity. Indications are many that one of the war’s consequences in Russia is a new Nationalism, not temporary and jingoistic, but the expression of the interests of the Russian bourgeoisie.

Consider a map of the world, and you immediately perceive how preponderant is the part thereof not developed capitalistically. South America is still “on the make.” There is a powerful nationalist agitation in Egypt and India, aiming at the overthrow of British rule; an agitation equally indispensable in Persia. One useful result of protectorates and colonialism among “effete” civilizations is the stimulus given to the spirit of Nationalism by the introduction of partial Capitalism. The problems of China and Mexico are largely identical, national: creating a free peasantry, shaking off the clutch of foreign Capitalism, developing a homogeneous national bourgeois class which shall establish bourgeois institutions and bourgeois democracy; that is, national Capitalism. Foreign financial and economic penetration in China and Mexico is a danger to normal, fundamental progress, which only the rise of a strong national bourgeoisie can avert. Unless national Capitalism assumes dominance, China and Mexico will decay as Turkey decayed.

At this point an important query suggests itself: Is Nationalism necessary in fully-developed Capitalist nations? It is an illusion to conceive now of fully-developed Capitalism. Capitalism still has to complete its cycle of development; and in this completion Nationalism plays an important part.

In completing its development Capitalism passes through the phases of State Capitalism and State Socialism. State Capitalism means the political synthesis and economic conservation of all sections of the Capitalist class nationally; the rise of a more intensely national Capitalism with national egoism at its nth power. International Capitalist interests become more completely, though temporarily, subordinated to national interests. The basis and animating spirit of State Socialism is fundamentally nationalistic, imbued with race prejudice and nationalist hatred of immigration. State Capitalism and State Socialism imply a large measure of social reform; and as social reform prospers and the interests of larger social groups are conserved by government, the sentiment of Nationalism acquires deeper power and reality because more actually identified with the well-being of the people. “State Capitalism and State Socialism are necessarily nationalistic…for when private industrial enterprise and competition have become insignificant, and the privileged classes include a majority of the population, a large part of the energies of the nation will be thrown into the competition of the governmental industries with those of other nations. There will be competition of nations instead of competition of individuals.”4 American Progressivism is intensely nationalistic; and its attitude in many ways suggests a sort of international piracy in favor of narrow national interests.

SOCIALISM AND NATIONALISM

The end of the Great War will see a new era of nationalist developments, not created by the war, but given a tremendous impetus by it. Capitalistically undeveloped countries will have an opportunity for larger industrial activity and develop a higher capitalism. State Capitalism and State Socialism will be given a powerful impetus by events in Europe. This means, of course, new and stronger national antagonisms; but this does not necessarily mean a new era of armament and war. As governments cease to represent merely a section of the ruling class which profits by war, and through State Capitalism represents the interests of the whole ruling class, war loses its inevitable character and frequency. The dangers of the new Nationalism are of a different sort and more directly affecting Socialism.

Socialism must cease doing the ostrich act. It must recognize the potency and social reality of Nationalism, and while recognizing Nationalism as a fact organize on a strictly non-nationalistic basis. A new series of nationalist development being inevitable in the social process, Socialism cannot set itself in opposition. But we must assume no responsibility for it. Nationalism will perform its function without us. We must concern ourselves with other and more revolutionary things. Considering the insistent influence of progressive nations upon the less progressive, and the rapid rate of progress in modern society, these new nationalist developments will rapidly perform their function, undoubtedly within our own generation. This means that Socialism must prepare itself for the revolutionary task of the immediate future,—the fundamental task of Socialism.

But while not participating in the impending social changes, we should not detach ourselves from living conditions. The “intellectual” and platonic revolutionist is useless, and ridiculous. Socialism must identify itself with a vital social force,—a developing, aggressive force. We must emphasize a new culture, the spirit of the future; and develop a conception of life more vital and revolutionary than State Capitalism and State Socialism. But all this must be done as an expression of the activity and interests of a class ascending to power.

Social reform being an integral part of the new Nationalism, the temptation will be strong to many Socialists to participate therein. Many will distinguish between reformism and Nationalism, denying that in this connection reformism is nationalistic in spirit and scope. But that distinction will have to be made; and we should not forget that reformism was an important factor in the German Socialist collapse. Ours is a deeper cause than that of social reform; and all the more must we avoid reformism considering that social reform is being organized by progressive Capitalism. While the new Socialism recognizes the social process as a whole, it cannot express all phases of that process; it can express only a particular phase, that which is most potent of the Socialist revolution.

As the new Capitalism consequent upon the Great War develops, the unskilled proletariat becomes more numerous, more powerful and homogeneous; “organized by the very mechanism of Capitalist production itself” (Marx). These unskilled workers are the pariahs of the new Capitalism. But simultaneously they become our revolutionary class, dynamic agency of the revolution which must climax the nationalist developments. The unskilled proletariat expresses those final class interests the triumph of which means the end of all class rule, and in this sense becomes the instrument of revolutionary Socialism.

The immediate task of revolutionary Socialists after the war, however, will be an uncompromising fight against “Nationalistic Socialism.” The collapse of the International being due to Nationalism, the natural conclusion should be, “Drive Nationalism out of the Socialist movement!” The tendency among conservative Socialists, however, is to justify and even glorify Nationalism. This tendency is general. In the American Socialist party it is expressed by Morris Hillquit. According to a New York Call report, Hillquit in his second Cooper Union lecture on the war said: “If there is anything the war can teach us, it is that when national interest comes into conflict with any other, even class interest, it will be the stronger. National feeling stands for existence primarily, for the chance to earn a livelihood. It stands for everything that we hold dear,—home, language, family and friends. The workman has a country as well as a class. Even before he has a class.” The implications in these utterances are obvious, and menacing. If the workers have a country before they have a class, then national interests are superior to proletarian interests, and the chief purpose of Socialism becomes the conservation and development of national interests—all of which is good State Socialism.

The lines of the struggle against “Nationalistic Socialism” are now visible in the German Party,—a struggle within the party of the revolutionary minority against the nationalistic majority. It is immaterial which triumphs; the struggle is bound to end with one group on top, the other out—unless compromise prevails, and that would be suicidal. A “split” is necessary; and this “split” will allow “Nationalistic Socialism” to gradually coalesce with bourgeois Progressivism, State Socialism being their objective. This coalition compels Socialism to become more and more revolutionary, and Socialism appears stripped of its illusions and non-proletarian characteristics. It is at this stage alone that the fundamental revolutionary problems of Socialism, economic, political and cultural, particularly the role of the unskilled, receive adequate consideration and expression.

Our fight against “Nationalistic Socialism” must be a fight against all its manifestations. “Nationalistic Socialism” involves a multiplicity of non-proletarian and non-revolutionary characteristics. Militarism is one of its dangers. Socialism is against militarism. On this point there can be no equivocation. Socialism is international or it is not. If it is not, then Socialist legislators may vote military appropriations, encourage mightier armaments, prepare for universal carnage. If it is international, then under no circumstances can Socialists vote military appropriations, and we must unflinchingly carry on our anti-militaristic and anti-patriotic propaganda. But that is not all. Socialism may be against militarism and remain nationalistic; pacifist Socialism is not necessarily international Socialism. While the fight against Nationalism in our movement necessarily rages around the Socialist attitude to militarism, we must fight to crush “Nationalistic Socialism” itself, and not a particular manifestation alone.

A NEW INTERNATIONAL

In re-organizing the International, it is not sufficient to exclude militaristic Socialists and “Nationalistic Socialism.” A more drastic re-organization is indispensable. The new International should rigidly exclude all Socialist elements tainted with Nationalism; dynamically emphasize its opposition to militarism and deny admission to all parties and groups in any way militaristic. But after that is done, the task of re-organization will have just begun. And one of the first problems which will then press for solution will be, “A Socialist International or an ‘International of Labor’?” The old International, indulging the illusion that any part of the working class fighting Capitalism was ipso facto class-conscious, admitted trades-unions and labor parties that repudiate the class struggle, and the policy of which is indistinguishable from bourgeois liberalism. Because of this policy, and other factors, the old International gradually lost its Socialist stand-point. The new International will have to base itself on a recognition exclusively of groups, economic and political, that are Socialist—abandon the ambiguous criterion “labor” as a test of admission.

Another necessary thing is that decisions of the International shall have more binding power than in the past. The International cannot legislate for the whole international movement; but if it is to have no power at all, and if its decisions can be repudiated, as the American Socialist party repudiated the Stuttgart resolution on immigration, then the International becomes useless and meaningless. National autonomy is necessary; but it is just as necessary that the national groups shall be coordinated into an International with power to act in an international crisis and in matters of international policy. An indispensable condition for a real International will be the willingness of a particular national group to forego its national interests and autonomy in favor of the larger interests of the International as a whole.

As the International loses its overwhelmingly European complexion and the new world-developments proceed, the International will see the necessity of formulating a policy concerning the “backward races.” And what shall be our attitude to this problem, the most formidable issuing out of the Great War? Largely one of insisting that these races must be left alone to develop their own economic and cultural resources. European and American interference must be courageously and consistently opposed. Workers of the “backward countries” are not to become the vassals of the Capitalist Class and Aristocracy of Labor in Europe and America. The rapid development of the “backward races” will shortly produce movements to shake off alien domination; and this means new antagonisms between the East and the West. Should not the policy of the International stand by the East in order to avoid race-war, and stimulate progress and international comity?

ANTI-IMMIGRATION AND RACE-WAR

The American-British doctrine of racial exclusion is a menace now, and bound to become more menacing as the great East awakens to independence and power. Anglo-Saxons demand the “open-door” in China, exploit India, but shut the door tight against the Hindoos, Chinese and Japanese in America, Canada and Australia. Here in America this stupid prejudice and anti-immigration propaganda is growing stronger. The East has no racial quarrel with the United States or England, unless Anglo-Saxon prejudice provokes a quarrel. A book just published, Japan to America, composed of representative Japanese opinion on the relations between Japan and the United States, makes it clear that the danger lies in the unfriendly attitude of Americans: “Japan is desirous of being friendly with the United States, but feels hurt that there is prejudice against her civilization and her ideals because her people have yellow skins.” The Japanese are human and won’t meekly accept insults.

American race prejudice, by arousing racial enmity and denying the mobility of labor, may instigate race-war. The American craft unions are working to this end with their reactionary anti-immigration attitude which illusorily seeks to protect craft interests. And the American Socialist party, dominated by the ideals of the craft unions, cravenly echoes their anti-immigration stupidity.

Socialism cannot tolerate race prejudice and anti-immigration. Its internationalism must be real. Surely Socialism may not adopt a policy inferior to the views of Viscount Kaneko voiced in Japan to America: “If, therefore, there is anything Japan has to teach the white nations, it is the fact that mankind is a one and indivisible whole, that the yellow race is not inferior to the white, that all the races should co-operate in perfect harmony for the development of the world’s civilization.” Upon Socialism rests a tremendous responsibility. The danger of potential race-war is a call to action, and demands a revolutionary international Socialist policy.

PARLIAMENTARISM AND ECONOMIC ACTION

Parliamentarism showed itself utterly futile in the European crisis. The supreme utility attached to parliamentarism was a strong factor in destroying the morale and taming the fighting energy of the German Socialist movement. Marx bitterly satirized those who consider parliamentarism creative and dynamic. Even had the German Socialists had the will to oppose the war, what effective means could they have adopted? Parliament had no control over events; all the Socialist parliamentarians could have done was to vote against the war credits, which would not have averted war. The unions had no initiative, the political movement having always played the dominant role. A General Strike? But a General Strike implies virile economic organization, conscious of its power and aware of its decisive utility, accustomed to playing a leading part and not acting in obedience to a parliamentary-mad bureaucracy. The German Social Democracy has always denied the unions any vital function, conceiving them as an auxiliary of minor importance with no revolutionary mission to perform.

Parliament—political government—is essentially a bourgeois institution, developed by the bourgeois in their fight against feudalism, and expressing bourgeois requirements of supremacy. Socialism, of course, cannot ignore political government; it is an expression of class war in capitalist society, and political action becomes a necessary form of action. But the proletariat must develop its own fighting expression, its own organ of government,—the revolutionary union. Socialism seeks not control of the State, but the destruction of the State. The revolutionary union alone is capable of dynamic, creative action.

Economic action assumes dominance in our tactics as the Socialist movement becomes more definite and aggressive; political action becomes an auxiliary. Revolutionary unionism develops the initiative and virility of the proletariat, unites the proletariat as a fighting force. It organizes the proletariat not alone for every-day struggles but for the final struggle against Capitalism. Revolutionary unionism prepares the workers for their historic mission of ending political government and establishing an industrial government—the “administration of things.” Revolutionary unionism, finally, can secure for the workers all necessary immediate reforms through their own efforts, without the action of the State. In this process Revolutionary Unionism develops itself as the means for the overthrow of State Socialism.

These are the larger outlines visible in the future of Socialism. The Great War will simply produce new conditions for new Socialist action—not the Revolution. Socialists have believed that a universal war such as that now in progress would end in Revolution. In a letter I received recently Lucien Sanial says: “The present European War is pregnant with a mighty revolution.” Engels prophesied revolution as a consequence of the Great War which “must either bring the immediate victory of Socialism, or it must upset the old order of things from head to foot and leave such heaps of ruins behind that the old capitalistic society will be more impossible than ever and the social revolution though put off until ten or fifteen years later, would surely conquer after that time all the more rapidly, and all the more thoroughly.” But it is now clear that the Great War does not mean Revolution; all it will do is provide the necessary factors for new Socialist action productive of ultimate revolution. Let us direct our efforts accordingly.

NOTES

1. “We will have to go back twenty years and pick up the broken threads of the revolutionary movement where both the leaders and the rank and file of the German Socialists laid them down so long ago, and understand the principles which will permit a re-birth of the movement.”—Frank Bohn, in the International Socialist Review, December, 1914. That is our task; but not all of it. We must rescue Socialist principles out of the muck of compromise and confusion, and then fearlessly apply them to contemporary conditions to develop the new tactics of Socialism.

2. Chief among the aspects of Capitalism neglected by Socialists are its economic elasticity, the new vigor yielded Capitalism by the tremendous untapped resources of pre-capitalistic countries, and the necessity of nationalism as an instrument in the industrial and political development of these precapitalistic countries.

3. Socialists who monotonously intone, “Capitalism caused the war,” and interpret “Capitalism” as meaning the profits of industrial capital or the “capitalist mode of production,” should consider that agrarian interests were largely responsible for Austro-Servian antagonisms. The Hapsburg monarchy is run by the feudal agrarian caste, which to make big profits prevented low prices by imposing prohibitive tariffs on agricultural products. These tariffs were aimed at the Balkan states, particularly Servia, whose exports consist almost wholly of agrarian products. Among other factors, ascending Capitalism requires a free peasantry, free in the non-feudal sense. At this epoch problems of Capitalism are largely translated into terms of agrarian interests. Napoleon was an instrument of ascending Capitalism, yet his regime was predicated upon the peasant class recently freed from feudal vassalage. Stolypin’s agrarian reforms in 1906 by destroying the remnants of feudal agriculture in Russia provided one of the indispensable factors of Capitalist development, which since then has been rapid. An independent farmers class is necessary for national Capitalism in Mexico.

4. William English Walling, Progressivism and After, p. 293. The war lends a new and deeper interest to this book. It throws light on the collapse of German Socialism, and is tremendously suggestive of the new tactics Socialism should adopt. The chapter on “Nationalistic Socialism” is perhaps the most valuable in the book, and particularly illuminating at this time. One need not accept Walling’s sharp distinctions and peculiar emphasis on what may be called “social automatism.” One must draw the conclusion Walling does not—that the existing Socialist party has no Socialist function to perform unless completely transformed in theory and tactics.

New Review was a New York-based, explicitly Marxist, sometimes weekly/sometimes monthly theoretical journal begun in 1913 and was an important vehicle for left discussion in the period before World War One. In the world of the Socialist Party, it included Max Eastman, Floyd Dell, Herman Simpson, Louis Boudin, William English Walling, Moses Oppenheimer, Walter Lippmann, William Bohn, Frank Bohn, John Spargo, Austin Lewis, WEB DuBois, Maurice Blumlein, Anton Pannekoek, Elsie Clews Parsons, and Isaac Hourwich as editors and contributors. Louis Fraina played an increasing role from 1914 on, leading the journal in a leftward direction as New Review addressed many of the leading international questions facing Marxists. The journal folded in June, 1916 for financial reasons. Its issues are a formidable archive of pre-war US Marxist and Socialist discussion.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/newreview/1915/v3n01-jan-1915.pdf