I never imagined doing this page would begin an interest in avant-garde 1930s dance, but it has. Get acquainted with the now, sadly, lost art of revolutionary solo dance with Steve Foster as he reviews the Workers Dance League of New York City’s fall, 1934 performances.

‘The Revolutionary Solo Dance’ by Steve Foster from New Theatre. Vol. 2. No. 1. January, 1935.

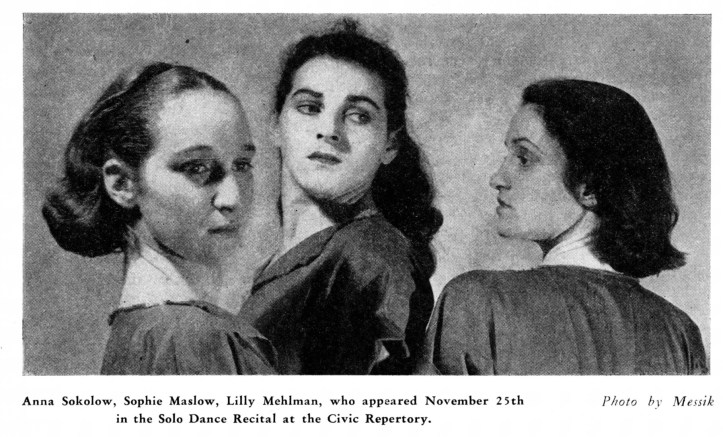

SURELY, in America there is maturing a new revolutionary art. In two performances at the Civic Repertory and Ambassador theatres on November 25th and December 2nd, young dancers from the Workers Dance League gave stirring evidence of their progress in the dance. Their dance is unhampered by an outmoded tradition, is flexible and broad in its forms and realistic in its approach to social and artistic problems. It is a dance presenting new aesthetic values and a variety of creations superior to the limited, false and artificial products of the day. Mass audiences participate in this dance in that they demand the dancers present significant, creative expressions of the social milieu in which they live. They test the performer by this rigorous and difficult standard, and inspire her by their ready response and appreciation of her achievements. The audiences at these two performances were very enthusiastic, and the dancers were talented and praiseworthy.

Lillian Mehlman, in her solo offering, Defiance, was a genuine spitfire on the stage. Her dynamic tempo was sustained from the first to the last gesture. Defiance was surcharged with energetic rhythms and direct, forceful, electric movements. Her dance composition was the spirited challenge and expression of a defiant rebel.

By comparison Awake by Miriam Blecher, March by Nadia Chilkovsky, and Challenge by the dance trio, Sophie Maslow, Anna Sokolow, and Lillian Mehlman, were less forceful. The composition of the March was more original and imaginative than Awake, which was little more than a well-performed cliche. The choreography of Challenge was interesting and varied but the dance lacked the spirit and force of Defiance. The upward thrust and leap of the central figure between the two crouched dancers did not convey its intended challenging and explosive character.

With true lyricism, Sophie Maslow, in Themes From a Slavic People, danced a composition of fine rhythmical patterns and gracefully captured the spirit of the folk dance.

Miriam Blecher’s three dances to negro poems were her most successful efforts. She made effective use of her recitations, which accompanied and harmonized with her movements. In brief, staccato motions, she presented synoptic dance dramas that expressed her convictions and sympathies. Her composition, The Woman, though well-performed, was too vaguely conceived and not fully visualized. It dealt with a generality, and emphasized sybaritic, feminine features instead of depicting a specific type or working-class character. In contrast, Nadia Chilkovsky’s portrayal of a homeless girl was much more realistic.

Nadia Chilkovsky’s dance, Parasite, was a perfectly conceived study of the duplicity behind the well-bred leisure-class mask of gentility. Gestures of refinement and grace were subtly emphasized and then contrasted to the barbaric, grasping, greedy actions that motivate the capitalist. When the over-reaching, bloated creature burst with his own greed, fell and died, there was no need of explanation; the symbol was clear and the contrast vivid. The artist created in the best and most precise manner possible.

The wit, liveliness and humour of Anna Sokolow’s compositions are rarities in the dance. She is the most professional performer. She is in command of her technique, aware of what she can accomplish and the effects she can produce.

The satire in Parasite appears heavy handed besides the deft, humorous touches Anna Sokolow employs. The Romantic Dances, performed with fine balance and grace, are parodies that rip the pretense from the romantic poseur. In Histrionics, there is the same verve and laugh-provoking wit and humour. But there is a tendency towards the superficial, an emphasis on the droll gesture. Histrionics, instead of a caricature of theatrical affectations, could well have been a study in hysteria. The same frenetic, affected, madly exaggerated qualities could have been adapted to a portrayal of the duality of an hysterical character and the frustration that lies behind such hysterics. Instead of a one-sided parody, a sober, understanding study of such a character could have been woven into a more profound dance.

Death of a Tradition, danced by the Maslow-Mehlman-Sokolow trio, in its exaggerated posturing of solemnity, its caricature of pompous and empty ritual, is magnificent mockery and burlesque sustained to the last, expiring, ridiculous gesture of a senile and meaningless tradition.

The opening stance typifies and sets the mood for Jane Dudley’s The Dream Ends, but the composition is not entirely effective. The dance is too vague, the exposition too lengthy. What is dreamed? Why does the dreamer awake? What disturbs and upsets his dreams? The dance is not fully realized. If the dancer sustained her movements to a cinematic slow-motion a greater effect of dreaminess and unreality would be obtained. Such unnatural tempo would be effectively utilized. The abrupt, swift awakening would have greater effect and would stand out in sharper contrast.

The work of Jane Dudley and Nadia Chilkovsky is similar in that both reveal a greater interest and insight into the social scene than their fellow-artists. In Chilkovsky’s Homeless Girl and Song of the Machine, and in Jane Dudley’s Life of a Worker, the two dancers experiment with machine and labor rhythms. In Time is Money, danced to a poem, Jane Dudley makes the most effective use of these rhythms. It is her finest dance composition and one of the best in the repertoire. There is no attempt, as in the disappointing, backward efforts of Edith Segal, to act the poem. The poem is imaginatively interpreted and acts as a dramatic accompaniment to the dance. The dance contains its own logic and composition. Work movements are designed and their tiring, maddening effects are conveyed. The conclusion, however, fails. It is not developed as part of the dance composition. Whereas he is a logical outcome of the idea of the poem, in the dance the financier is not brought out as a figure in opposition to the worker. The straight, inexpressive figure of the financier reveals that Jane Dudley was unclear and undecided as to his portrait. Some gesture or stance designed to typify the financier would help to clarify and perfect the final movement. Sound accompaniment, the well-timed, bizarre noises of machines, would add dramatic power to the dance. Time is Money also has excellent theatrical possibilities as a group dance.

With the exception of Edith Segal’s offerings, the dances were much superior to the previous work of the dance groups and solo performers in the Workers Dance League. The Workers Dance League is establishing an excellent repertoire. It’s young and talented dancers are developing themselves as mature artists of the new, revolutionary dance. They have already become an important force in the new theatre and the working-class cultural renaissance.

The annual International Theatre Week, sponsored by the International Union of the Revolutionary Theatre, takes place February 15 to 25. This occasion serves to acquaint the American public with the achievements and activities of the workers’ theatre arts in all lands. The League of Workers Theatres and the Workers Dance League are joining forces for this event, and the National Film and Photo League and Workers Music League are also expected to. Activities will include performances, lectures, and symposia. Plans are to send speakers out that week to any mass organization, trade union local, dramatic association, etc. that requests it. A special button for mass distribution will be issued. Material on the history and program of the international organization is being prepared, and will be available to all groups.

The New Theatre continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v2n01-jan-1935-New-Theatre.pdf