To show U.S. union militants the possibilities of industrial unionism, Paul Hoyer details what was among the largest and most important workers’ organizations on the planet, the German Metal Workers Union. Though reformist-led, with 1.6 million members is had a strong left wing and was a center of much militant activity. The union was dissolved and its property confiscated by the Nazis on May 2, 1933.

‘Deutscher Metallarbeiter-Verband–The German Metal Workers’ Union’ by Paul Hoyer from Labor Herald. 2 No. 6. August 1923.

Editor’s Note: The immense organization described below is still dominated by the conservative Socialist elements, and follows their general policies. This leaves its potential strength largely undeveloped. The left-wing forces are constantly increasing their strength within it, however, and promise soon to make of it a most powerful and militant weapon of the workers. The point of this article is to indicate the structure and workability of industrial unionism.

ТHE metal workers of Germany justly lay claim to being the greatest industrial union in the world. Consisting of 1,600,000 organized toilers, and representing 35 major crafts or trades in the metal industry, it is proud of several other things besides the fact that it brought virtually a whole industry under its jurisdiction. Among these are the following:

1. No trade that has given up its independent organization and amalgamated with the Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband has ever withdrawn, or even threatened to withdraw. No matter how large or small the trade, it has found that its interests were better taken care of in the large industrial organization than they were in the independent craft union.

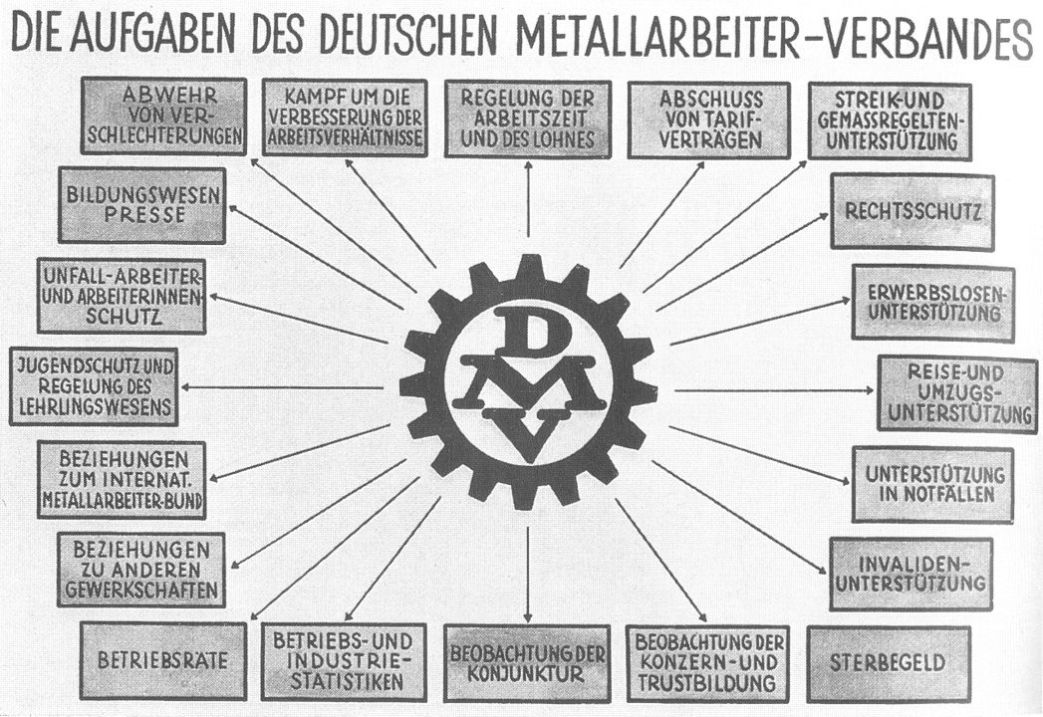

2. Thanks to the strength that comes from union and numbers, the Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband is able to furnish to its members special facilities–legal aid, library service, special courses for works council delegates, unemployment, strike and death benefits, and a research bureau–such as no other union in Germany or perhaps in Europe can supply.

3. Though Germany is not a Soviet state, yet the beginnings of the Soviet idea have been put into effect, in some faint degree at least, in all the plants controlled by the union through the application of the works councils law.

4. While amalgamating practically all the numerous trades that enter into the metal industry into one big union (Only two trades still remain outside the organization–the coppersmiths and the machinists and firemen. These two bodies, numbering respectively 7,000 and 90,000, will probably join the larger unit shortly) every possible concession is made to the craft feeling and to the desire for local autonomy in that all the trades still hold their craft meetings, both local and national, and discuss their individual problems.

Structure of the National Body

Let us trace the structure of the union from the top down through the smallest local and see just how it works organizationally:

The highest legislative body is the national convention which meets at least every two years, and which is composed of delegates chosen by referendum on the basis of one delegate for each 4,000 members. Only members who have been in the organization for three or more years can be elected as delegates.

To conduct the work of the organization, this national convention elects a general executive board of 22 members, consisting of 4 presidents, 2 treasurers, 5 secretaries, and 11 associates. The 11 associates must live at the seat of the national body (Stuttgart), and must be men active in their trade–in other words, actual metal workers. (The annual meeting also elects two editors of the national organ, the “Metallarbeiterzeitung,” but these men have only an advisory voice in the General Executive Board.)

A second body chosen by the national convention is the Control Commission of 5 members, which has its seat at some city other than that of the national offices, and which acts as a sort of watchdog of the treasury and of the General Executive Board.

The Advisory Boards

But, though the G.E.B. is the main executive branch of the national union, it is not supposed to venture upon important situations without consultation. The constitution provides for two consultative bodies, the so-called Narrower Advisory Board (Engerer Beirat), and the Extended Advisory Board (Erweiterter Beirat). On less important matters, and whenever in its opinion such advice is necessary, the G.E.B. calls together the smaller board, which is made up of the various district organizers, of the two presidents of Local Berlin (which because of its size of the first editor of the Metallarbeiterzeitung occupies a special position in the organization) and of the chairman of the Control Commission.

More important is the Extended Advisory Board. It is called together on all important occasions. It decides upon programs of action and questions of tactics, attends to the re-districting of the membership geographically, and approves of collective agreements. It is composed as is the Narrower Advisory Board, but in addition the various districts (see below) in the country elect one member each to this Extended Advisory Board for every 50,000 members, with a limit of 3 members for any one district. The Extended Advisory Board must be called whenever the Control Commission so desires, or whenever one-half of the representatives of the districts so demand.

The above are the various bodies with national jurisdiction that deal with affairs of the whole industrial union. Membership in any of these bodies is dependent, not upon the particular trade of the individual, but upon his record as a worker in the metal industry. The trade or craft feature is taken care of in another way: the various trades as such also hold their national conventions and maintain national and local organizations for purely professional reasons. Once a year, as a rule, each of the 35 trades amalgamated in the Metallarbeiterverband holds a national convention and, as such questions as wage agreements, working conditions, social policy and the like are taken off its shoulders through the larger body of which it is a part, each trade can devote the national conventions to intensive discussion of professional problems. Thus, the argument of people who object to the industrial union idea on the ground that the feeling of trade solidarity is weakened falls to the ground: on the contrary, professional interests receive even more attention in the large industrial union than they do in the purely craft union. And even the smallest trade can afford to hold such a convention, as the Metallarbeiterverband as such foots the bills.

Subdivisions of the National

We now come to the subdivision of the amalgamated national body. The G.E.B. and the Extended Advisory Board together divide up the country into districts, of which there are now 17. At the head of each district the G.E.B. places a Bezirksleiter, or district organizer, who might be compared to an A.F. of L. national organizer stationed in a given locality. The G.E.B. cannot, however, simply put any favorite it wants into such a place. It must choose him from a list of candidates selected on a competitive basis and certified to, with recommendations, by the Extended District Commission, a body whose relation to the district administration is similar to that of the Extended Advisory Board to the G.E.B.

The district organizer with his assistants has two consultative bodies placed over or beside him, the Narrower District Commission of 4 members (whose principal function is that of checking up on the finances), and the Extended District Commission of II members (which checks up chiefly on the business efficiency of the district organizer). These district commission members are chosen by a body whose relation to the district administration is parallel to the relation of the national convention to the G.E.B.–namely, the district conference.

The district conference, like the national convention, is a delegate meeting. There is one delegate for every 1,000 members in the component locals, with the proviso, however, that no local can have more than three delegates. The district conference meets at least once a year, and voting is done on the basis of the number of members represented. In other words, if a delegate represents 1,025 workers, he casts 1,025 votes. Thus no large local suffers from the fact that it can have only three delegates.

The district conference, as already alluded to, elects the district commissions that act as checks and balances upon the district organizer. They also choose the district representatives on the Extended Advisory Board of the national organization.

The Locals

We come now to the locals, from which are chosen the delegates to the national convention, and from which are elected the delegates to the district conferences. It is in the locals that one sees best the grouping according to trades, and that one learns to understand the relationship of the works councils to the organization as such. As an example I take the largest of the locals, Berlin, with a membership of 150,000, or about one-tenth of the entire membership.

In the local, the members are divided in two ways according to trades and according to the shop or subdivision of industry in which they work. Of the trades within the federation, there are, as already stated, 35. To mention but a few of them: enamelers, locksmiths, plumbers, engravers, mechanicians, smiths and tool makers. The members in each of these trades elect their own Branchenleiter–branch or trade organizer (administrator).

Secondly, the members are classified according to the shop in which they work. The whole industrial area of Berlin is divided into 25 districts, with a district organizer in charge of each district. This organizer is chosen in the following manner: in each plant the workers are organized in a works council. These works council choose from their midst certain delegates (Betriebsrate), or shop stewards, who represent the workers in their dealings with the bosses. These delegates also select the district organizers, the works council delegates in each district choosing the organizer for that district.

Thus there is a sort of dual organization: the branch or craft administrations, of which there are 35 in Berlin, and which function as professional organizations irrespective of where the man works; and the district administrations, of which there are 25 in Berlin, in which people are grouped together by whole industries in the different sections of Greater Berlin.

The dual character appears in connection with the general meeting of the local: both the districts–that is, the industrial units and the branches that is, the craft units–send delegates to the general meeting on the basis of 3 delegates for each branch and district, plus the branch and district organizers. In addition, a general meeting of all works councils delegates is held, from which delegates not exceeding 50 in number are sent to the general meeting. In other words, not only are delegates chosen by crafts and geographical location, but also by virtue of their being in a particular shop or plant. And finally, the numbers at large, irrespective of trade or shop, choose a delegate-at-large in the general meeting on the basis of one delegate for every 300 members.

The general meeting in turn elects the Narrower, or Inner Administration, consisting of 2 chairmen with equal powers, 2 treasurers, 5 “revisors” and 3 associates. The latter eight work without pay. The general meeting also elects such employes as secretaries, editors, etc. Finally, besides the Inner Administration there is a Mittlere Verwaltung or Middle Administration, composed as follows: the members of the Inner Administration, the secretaries, the 25 district and 35 branch organizers, and one representative each of the 7 main industrial groups into which the work councils delegates are classified for this purpose (foundries, vehicle industry, machinery construction, metal manufacture, electro-industry, delicate mechanisms industry, small trades). This Middle Administration, it will be observed, combines all the features of the metal workers’ union-industrial, trade, and geographical organization.

Wage Agreements Concluded by Industry

One of the most obvious manifestations of the power inherent in the industrial union idea comes in connection with the conclusion of wage agreements.

There the union functions as a whole. Wage agreements are made, not for this or that trade, but for the entire industry. No matter how small or weak the group, it has the combined strength of the entire organization behind it.

The union deals with the industrials by cities and localities, and not as a national unit. This is due to the fact that living conditions, conditions of work, etc., are different in a city like Berlin than they are in a much smaller city like Halle, or in the country districts. Union leaders explained to me that if a national wage scale were to be adopted, this would naturally have to be in the nature of a compromise, and many cities where living costs are exceptionally high would fare badly. Under the present arrangement, every district concludes its own agreements, with the result that local conditions can be duly observed.

Within the locality, however, the agreements are uniform for the entire city and for all workers in the industry. All workers, of whatever trade, are divided into five groups, depending upon length of service, ability, technical skill required, etc. The union speaks of three kinds of workers–skilled workers (Gelernte), workers who came from another trade into their present trade and are now doing skilled work in it (Angelernte), and unskilled workers (Ungelernte). The Gelernte and the Angelernte usually fall within the first three classes, and the Ungelernte unskilled–within classes IV and V. The works council in each plant decides into which of the five wage categories the member is to be put, and when he is to be advanced from a lower to a higher class.

The wage agreement, then, that is made with the bosses collectively calls for such and such wages for all workers in Class I, such and such for workers in Class II, etc. The bosses accept the classification into which the works council puts each worker, or else refer the case to arbitration.

Other Advantages of Industrial Unionism

One reason why the Metallarbeiterverband has been so eminently successful in conducting its wage negotiations is the fact that so large an organization can afford to maintain an adequate staff of statisticians and economic experts who can match the experts of the employers. The union experts obtain mastery of all details of the trade, and it is next to impossible to “put anything over” on them. Supposing an employers’ representative argues that his firm cannot give higher wages because of such and such adverse conditions: the experts of the metal workers’ union are in a position immediately to analyze the facts and figures upon which this assertion is based, with the result that the bluff is usually called.

The strong financial condition of the large union further makes it possible to conduct a regular school, or college, for works council delegates. The delegates are sent there at the expense of the union, and they learn cost accounting, analysis of balance sheets, labor legislation, and a thousand and one other things.

Just as the wages are divided into five classes, so also are dues and insurance benefits. Here, again, a uniform basis obtains for all the trades within the Verband. Thus a worker’s dues are assessed, not upon the basis of what particular trade he belongs to, but rather what class of worker he is (I-V), irrespective of the trade.

On the question of strikes, the greatest possible autonomy is provided for the individual localities and crafts. According to the constitution, strikes must be sanctioned by the G.E.B. But the constitution also provides that “the authority to call strikes may be delegated to locals of more than 3,000 members.” In practice, the G.E.B. has acted largely in an advisory capacity in purely local strikes, and has reserved its energies for the fights of state or national scope. Likewise the greatest possible freedom is left to a craft to conduct a local strike. The industrial unit takes a hand only when other interests beside the one craft are involved.

Historical Retrospect

In conclusion, a few words about the history of the union, especially as concerns the gradual amalgamation into one organization of all the trades in the metal industry.

Before the advent of Bismarck’s notorious anti-Socialist law of 1878, Germany witnessed the usual guerilla warfare between the various groups of theoreticians in the labor movement, with the result that the organized workers, instead of advancing by a united front against the common enemy, capital, preferred to waste their strength in internal rows. But after Bismarck had put all organized workers under the ban, these bethought themselves of their folly and worked together more harmoniously.

Among the first to realize the necessity of organizing the whole industry were the metal workers. By 1888 the Allgemeine Metallarbeiterverband Berlins und Umgegend was formed, despite the fact that a number of the older officials of the craft unions opposed the idea. It led a struggling existence, however, and embraced only relatively few trades and few members within these trades. Constant knocks by the bosses then drove home to the metal workers with ever greater emphasis that they could never succeed if they remained mere craft unions. Some form of amalgamation seemed imperative.

There were two currents of thought as to how to bring this about. One group believed that it was sufficient to bring all the trades in the metal industry together into one federation, much as all the internationals in the United States are brought together in one A.F. of L. The others argued that this was not enough–that in modern industry all the various trades work together under a common boss in one industry, and that therefore the worker, too, must be organized according to industry. Therefore, while the various trades might still maintain their professional organizations, yet they must give up to the larger unit certain prerogatives, such as concluding wage agreements, determining social policy, calling strikes, etc. Twelve trades were ready to take this step, and together they founded the Metallarbeiterverband of Berlin in 1897. on its present basis.

Meanwhile nationally, too, the same idea had been gaining ground, and during the same year the powerful Berlin organization joined the Deutscher Metallarbeiterverband.

After that progress was rapid. Slowly but surely the Metallarbeiterverband swallowed up the smaller trades in the metal industry until today, as stated at the beginning, but two trades remain outside the fold.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v2n06-aug-1923.pdf