The activities of the Blanquist student group at the Universite de France, including a young Paul Lafargue, around the insubordinate, and seditious, journal Candide; their suspension and an early student strike in 1865. Wonderful history this.

‘A Note on Our Tradition’ by Raoul Marin from Student Review (N.S.L.). Vol. 3 No. 5. Summer, 1934.

Our student struggles boast an old, precious tradition.

In the France of the Second Empire, the man who roused students to organization and action was Louis August Blanqui, a most heroic and ambiguous figure. The fiftieth anniversary of his death passed three years ago virtually unnoticed. Today, Blanqui is chiefly remembered for his theory that a small and resolute minority can shock the masses into motion and victory by a sudden opportune stroke. In his own times, that doctrine moved men to action, and high in the Blanqui faith was a remarkable group which received its initial revolutionary baptism as students in the Universite de France. Two of Marx’s sons-in-law, Paul Lafargue and Charles Longuet, began as members of this Blanquist group. What these students were like can best be indicated by retelling the story of what was perhaps the first international student congress on record.

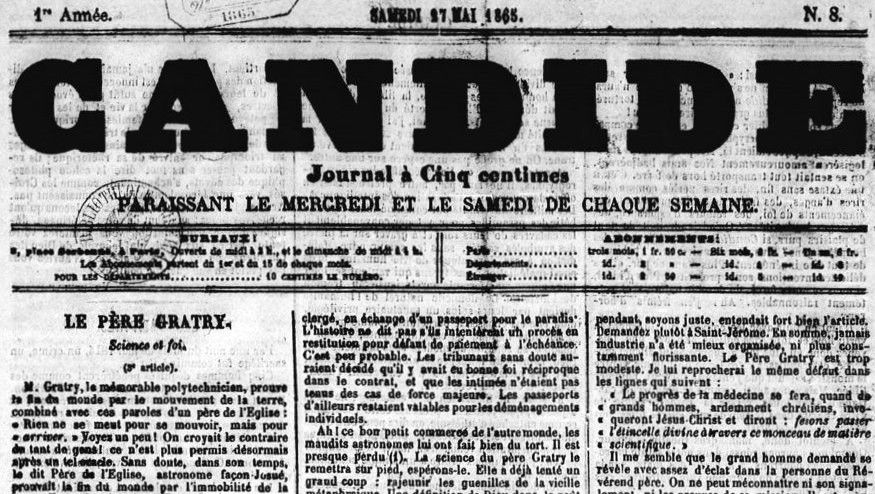

We hear of them first when in May, 1865, some of them undertook a journal dedicated to “the criticism of religion, science and philosophy.” Tongue in cheek, they named it le Candide. Blanqui himself frequently contributed under the signature Suzamel, a telescoped form of his wife’s two Christian names, Suzanne-Amelie. Gustave Tridon, the most famous of the young editors, was destined to write a famous work on the Hebertists.

Candide did not last long. They threw caution to the winds too soon. Too pugnacious treatment of burning social questions earned its suppression after the eighth number. Appearing twice a week, it had lasted just a month. To the Blanquists, however, such suppressions were as inevitable as birthdays. For example, Longuet began publishing a paper called Les Ecoles de France, suffered suppression, was jailed, fled to Brussels, changed the paper’s name to Le Rive Gauche and continued publication in Belgium.

Candide was not so fortunate. Vaissier, the managing editor, Turpin, the printer, Ponnat and Tridon, the editors-in-chief, were sentenced from one to six months in jail, with a stiff fine besides. But the paper had served them well. It helped to clarify their ideas, it gave them courage and the precedent of proclaiming their ideas beyond the limits of garret and cafe; it gained recruits to the cause. Above all, it was this last, the silent organizer in the university. A relatively small but remarkably cohesive group sprang up from nowhere. Blanqui’s call to arms: Atheism! Communism! Revolution! was enough for them.

Soon they were to show their mettle.

In October, 1865, an International Student Congress was called at Liege, Belgium, under eminently respectable auspices. The organizing committee invited the big-wigs of the various French parties, Duruy, Guisot, Thiers, Hugo, Litre and others. None of them came, however, and the congress was composed only of students.

The historian of this episode, Charles De Costa, was himself a participant. What he chooses to relate in his Les Blanquistes, is unfortunately mere outline. The rest must be surmised.

The congress opens with a parade in which the students march behind their national colors. The ceremony is solemn and impressive—except for a detail. All eyes turn on the French delegation. Their national colors are barely peeping out behind the drab black crepe. To all appearances the French delegation is marching behind a flag of mourning.

At the speeches presenting the flags and delegation, Aristide Rey, a medical student, gravely presents the crepe to the assembly, saying, “Coming from our country, France, where freedom is dead, we cannot bring the tricolor into Belgium.” Another student, Albert Regnard, rises to add that the French students felicitate the Belgians on their liberty. He deplores its absence in France where Napoleon III has strangled every semblance of freedom.

At the sessions proper, the congress is converted into a forum. Jaclard acts a biting, cynical piece against God and His deputies, the “black army,” the priests. Germaine Casse repeats as much of Blanqui on materialism as comes to mind at the moment. Lafargue, also a Blanquist at the time, delivers himself of a weighty attack against the money-bags, the usurers, the powers behind the throne.

Naturally, the Belgian press was scandalized. They made much of the flag episode and more of the speeches. Fundamental institutions were threatened, no less.

Under pressure from the Clerical wing of the Chamber of Deputies, the governing board of the Universite de France was hastily called together and the temporary suspension of the Blanquist leaders was voted.

The decision raised hell. The historian of the episode writes at this point not without restraint: “Such a decision naturally provoked the deepest emotions in the scholastic world and for several weeks the whole Latin Quarter seethed with excitement.”

Morning and evening, in campus, lecture room and cafe, meetings were held. Petitions of protest circulated without end. Finally, the word spread: Strike! No student must attend classes until the measures taken against their comrades are withdrawn.

Their strike technique was refreshing. In every class, both in the Law School and in the School of Medicine, as soon as the professor moved to begin work, they greeted him with rowdy applause, shrieks, stamping, whistling, general frenzy. Then a student rose and declared that the demonstration was not directed at the professor but at the Academic Council. The students were determined not to permit any classes until their comrades were reinstated. Familiar words!

The agitation continued for some time. What came of it? Our historian concludes mournfully:

“…it ended by dying out like all the demonstrations of the Latin Quarter. But not without results, principally from the young students just admitted from the Lycee, for by putting the atheistic and revolutionary doctrines of the Congress of Liege on the order of the day, the Congress continued in fact for a long time in the cafes at night.”

It will be seen that the affair was not without effect. It is hard to say why it was not entirely successful from the little we are told. We may surmise that it was at least partially due to the fact that the Blanquists did not undertake the slow, painful work of preparing the ground-swell of student activity and organization. A few brilliant adventures by a few brilliant generals—without armies—will never do.

The flame they handed down still burns. Clarity and program they lacked, but in spirit these Blanquists are surely comrades in arms separated from us only by the years.

‘Student Review‘ was the magazine of the National Student League, first edited by Harry Magdoff. Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/student-review/v03n05-sum-1934-student-review.pdf