Wonderfully detailed reports on the literature, theater, photography, theory, agit-prop, music, and cultural work of the Japanese Federation of Proletarian Art.

‘Activities of the Japanese Federation of Proletarian Art’ from Literature of the World Revolution. No. 2. 1931.

ECHOES OF THE KHARKOV CONFERENCE

The February, 1931, issue of the Japanese magazine “NAPF” contained material on the International Conference of Revolutionary Writers, held in Kharkov. The resolution adopted on the report of Comrade Matzuyama on proletarian literature in Japan, was printed in full as well as articles by Auerbach, Béla Illés and others, and also Selivanovsky’s “Results of the Second International Conference of Revolutionary and Proletarian Writers.”

“NAPF” and the magazine “SENKI” published the protest of the Kharkov Conference against the persecution by the police of “SENKI” (organ of proletarian literature in Japan) and the arrest of leading Japanese proletarian writers. Other protests were also published: those adopted by the delegations from Germany, America, England and China.

IN DEFENCE OF “SENKI”

At the beginning of this year the Association of Proletarian Writers of Japan conducted a wide campaign in defense of the “SENKI” (Fighting Banner) the very existence of which was threatened as the result of police persecution and the treachery of certain members of the editorial-staff. As a part of this campaign, the Central Committee of the Association of Proletarian Writers of Japan sent out a number of Writers “brigades” to various cities for the purpose of unifying local protests and organizing support of the working masses for the magazine. The first writers brigade went from Tokio to Kioto. It consisted of seven well-known writers: Tokunaga, Gakeda, Gyudzo, Kourogzima, Hasegaba, Tanabe and Kubokava. On the next day this group held a mass meeting in one of the largest halls of Kioto, which was attended by over 800, and this in spite of the repressive measures taken by the police (such as compelling all who entered the hall to fill out a form giving name, address, etc.). The speakers were subject to ceaseless interruption on the part of the police, who prohibited “sore” spots being touched upon. The writer Tagi, a member of the local branch of the Association, was arrested. The audience, many of whom were Kioto students, conducted itself orderly, holding itself in hand so that there could be no grounds on which the police could provoke undesired collisions and thus disperse the meeting. But when “SENKI’S” Declaration was read, the whole audience arose as one and in thunderous and prolonged applause expressed its willingness to give all possible assistance to the magazine.

The next day this ”brigade” arrived in Osaka and another well-attended meeting was held in one of Osaka’s large halls, and addresses were made before an enthusiastic audience which had braved a heavy downpour of rain in order to attend the meeting. Half of those present were workers. Three members of the “brigade” were arrested for their speeches (Tanabe, Kurogzima and Hasegaba) but were freed a few hours later owing to the pressure of a big street demonstration organized by participants in the meeting.

IN THE STRUGGLE FOR RAISING THE QUALITY OF THE COUNTRY-PRESS

The Secretariat of the Association of Proletarian Writers of Japan through its organ “NAPF” has issued a circular to all worker-peasant organizations. The association states its willingness to give all possible assistance to the newspapers and magazines published by these organizations, offering to provide them with literary works, to organize literary consultations, etc. The editors of numerous local workers’ and peasants’ publications have warmly hailed the initiative taken by the Japanese Association.

PERSECUTION OF THE “NAPF” MAGAZINE

The Japanese Federation of Proletarian Art (“NAPF”) has appealed to its readers among the workers and peasants to support the Federation’s organ, the monthly magazine “NAPF,” by creating their own agencies for distributing the magazine. It is pointed out that out of the four issues from September to December, two were confiscated. The toiling masses of town and country are called upon to fight for the freedom of the proletarian press.

The February issue of “NAPF” devotes much space to Soviet literature and questions of international politics. There is translation of a story by the Soviet-writer Gorbunoff, and a lengthy article entitled “The Five-Year Plan and Soviet Art” by the authoress Gudso Uriko who lived a long time in the U.S.S.R. There are also excerpts from the Soviet press testifying to the indignation shown by the working-class when the counter-revolutionary plots of the Promparty were exposed, and an article by Kitazoka called “Questions of Proletarian-Realism in Soviet Literature.” International relations were dealt with in a number of articles on the revolutionary literature of the West.

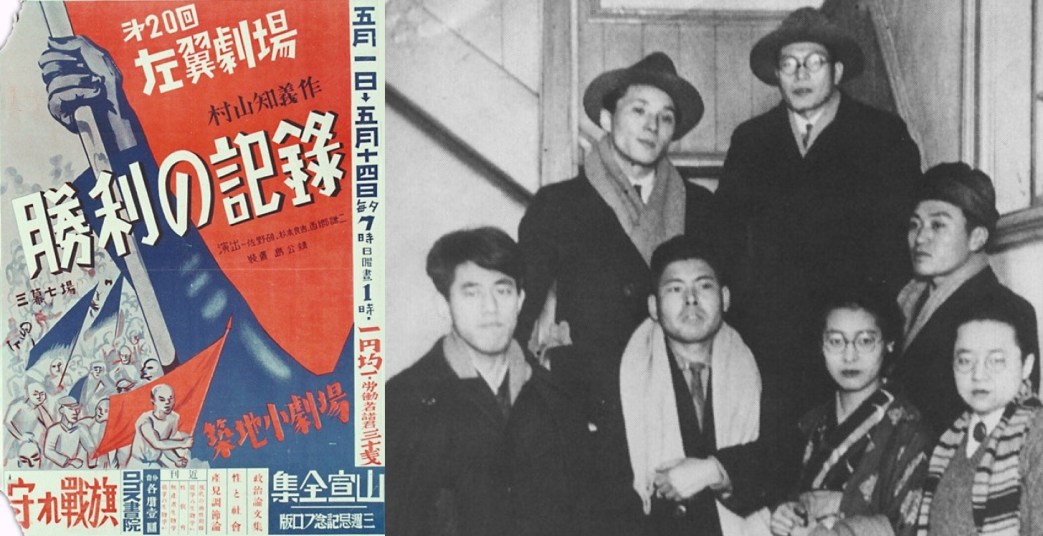

FOR A PROLETARIAN THEATRE

A society for the study of Japanese proletarian drama has been organized, which is composed not only of members of the Japanese Association of Proletarian Writers, but also of workers in the “left” theatrical groups and the “New Tsukidzi” theater. This society has issued the following declaration:

“The proletarian-theater movement has been developing rapidly during recent years. The theatrical associations affiliated to the “Association of the Proletarian Theater”: The “New Tsukidsi” Theater, the Masses Theater, and some few other theatrical societies, have played an important part in the proletariat’s struggle for liberty, notwithstanding severe persecution by the police directed against travelling-troupes.

“Now, when the question faces us of making the theatrical movement a mass movement, and of giving it a firmer basis, all proletarian dramatic societies feel very keenly the lack of a suitable repertoire.

“We call upon all playwrights and dramatic critics that accept our program to join us.”

THE PROLETARIAN THEATER AND THE VILLAGE

The Proletarian Theater “Matsue” has organized a travelling-troupe to tour the villages. The first performance was held in the village of Sakayot. There was an audience of over a 100, composed almost entirely of the poor peasants and their families. Three small plays were performed, together with fill-ins of poems and revolutionary songs. The police, as usual continually interfered, prohibiting everything they took exception to, and finally dispersed the assemblage by force. Strong indignation was shown by the peasants as the result of this overhand act.

The Tokio “Left” Theatre likewise sent out a travelling-troupe to perform before the peasants and workers of the countryside around Tokio. Their first performance, before leaving for the tour, was given in Tokio, and its working-class audience gave it a warm reception.

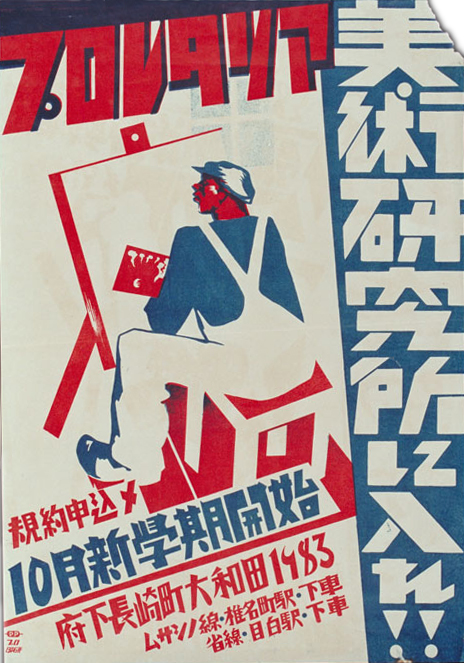

PROLETARIAN FINE ARTS TO THE MASSES

The Japanese Association of Proletarian Artists, which is affiliated to “NAPF” (Japanese Federation of Proletarian Art) is carrying out its slogan: “Proletarian Art to the Masses!” It recently published a third series of artistic post-cards calling them “Proletarian Post Cards.” This series contains eight post-cards drawn by proletarian artists, dealing with acute political questions of the day, such as for instance: “A Demonstration of the Street Car Strikers” by the artist Olodsova, “Against Unemployment” by Kida, “Out of the Factories and Mills” and “Against the Social-Democrats” by Koyama, “The Komsomol Girl” by Taradsima, and others. There were six other post-cards but these were banned by the police authorities.

This Association of Proletarian Artists has appealed to all Japanese artists to keep active in creating distribution agencies for broadcasting proletarian literature and art under the guidance of the “SENKI” magazine (“Fighting Banner”). In a leaflet the Society stresses that the purpose of these post-cards is to serve as illustrative material for organizers in mills and factories, and as a means of ridding proletarian families of the opium of bourgeois pictures and post-cards, and also to fan the burning militant spirit of the worker-peasant masses.

The publishing-department of the Association recently acquired a lithographic machine and thus is enabled to organize its own lithotypography for the printing of proletarian artists’ pictures. The second and third series of post-cards are already printed in this new shop.

NEW REVOLUTIONARY SONGS

As a supplement, the “NAPF” magazine has published two revolutionary songs issued by the Japanese Association of Proletarian Musicians. These songs are: “Against Harvest Confiscation” and “Our Spring.” The words of both are written by the poet Tagaki.

The issuing of these splendid songs shows that the Association of Proletarian Musicians which up to now had been the weakest trench in the firing line of proletarian art, is at last taking up its work seriously.

EXHIBITION OF PROLETARIAN PHOTOS

The photo-department of the Proletarian Cinema Society of Japan has recently organized an exhibition of proletarian photos. This exhibition covers a year’s work of the photo-department. In it are represented scenes depicting the life and struggles of the Japanese and foreign proletariat, photos of revolutionary leaders, mountings from films and theatrical-scenes.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

There has just been issued a new book by Yamada Saysbouro: The Development of the Theory of Proletarian Art in Japan. The author is a member of the Japanese Association of Proletarian Writers and a celebrated literary critic and theorist. Last year he published a well-known book “The History of Proletarian Literature in Japan.”

The author divides the development of the theory of proletarian literature in Japan into three periods. The first period covers from 1917 to 1925—1926; the period is that of the origin of the theory of proletarian literature, which brought forward the slogans “Popular Art,” “Literature of the Fourth Estate,” etc.

The second period is from the second half of 1926 until the beginning of.1928. It marked a turning point in the history of the Japanese literary movement. This period was marked with sharp theoretical differences of opinion, and during it “ukoumotism” (Right tendency within the Communist Party of Japan) was finally defeated.

The third period covers from 1928 to the present day, and is characterized by a most severe internal struggle for theoretical unity in proletarian art and for the hegemony of communist ideology.

Recently there was published a new book by the authoress Gudso Uriko Through New Siberia. This is her first book since her return from the U.S.S.R. and is devoted entirely to the grandiose construction of Socialism in the Soviet Union, to the life and struggle for Socialism of the many national-minorities living in the U.S.S.R. The writer was in the U.S.S.R. for three years and during that time was able to see fully and investigate the building-up of Socialism in the Soviet Union. Thus this book of Gudso Uriko’s will serve as a most appropriate answer to the campaign of lies and mud-slinging which the Japanese press is persistently carrying on against the USSR. Uriko, after her return from the U.S.S.R. immediately jumped into the work of explaining to the laboring masses of Japan the achievements of the Soviet Union, publishing a series of articles about the U.S.S.R. in Japanese newspapers and magazines. In the “SENKI” magazine her article “Why There is No Unemployment in the Soviet Union” was published, and is richly illustrated with photos of the giant enterprises being built in the U.S.S.R.

ACTIVITIES OF THE SECTION OF ART, LITERATURE AND LANGUAGE OF THE JAPANESE INSTITUTE OF PROLETARIAN SCIENCE.

The Japanese Institute of Proletarian Science which is similar to the Communist Academy of the U.S.S.R. draws together all the genuine Marxist forces of Japan for the purpose of the study and theoretical investigation of Marxist problems in various fields of science and art. The work of the Institute is carried on by the various sections: the section of Soviet literature; the section of the History of capitalism in Japan: the section of Art, Literature and Language etc.

At the beginning of 1930 the Section of Art, Literature and Language formulated its policy as the statement of Marxist theory in the study of art and Marxist investigation of the history of world art and of proletarian art. It was decided to form for this purpose the following subsections: 1) Sociology of art; 2) Modern Art; 3) History of World Literature; 4) History of Literature of the Meidzi epoch; 5) Proletarian art; 6) Proletarian cinematography; 7) Unification of transcription in translations. Of the 7 subsections, however, only 4 have been more or less active during the past year; the subsection of the Sociology of Art and those of Modern Art of the History of Russian Literature and of Proletarian Cinematography.

The Sociology of art subsection organized wide discussions based on Fritche’s Sociology of Art. A member of the subsection, the well-known proletarian critic Kurahara (now imprisoned on the charge of belonging to the C.P.J.) made a public report on “Imperialism and Art.” The Modern Art subsection has organized a number of lectures,—on the Soviet Theatre, on collective art, on surrealism. The subsection of Russian Literature discussed at its closed meetings three reports on the history of Russian literature beginning with the study of ancient folklore down to the beginning of the period of romanticism and realism. The report called forth a lively discussion.

A report was made by Kitaoko on the recent activities of the Russian Association of Proletarian Writers. The subsection of Proletarian Cinematography also organized several lectures dealing with various theoretical problems connected with proletarian cinematography.

Besides this, the section of Art, Literature and Language organised a number of public lectures: “On Bringing Art nearer to the Masses” (by Jamada); “Children’s Literature” (by Jemoto); “Problems of Proletarian Cinematography” (by Ivadzaki); “the NAPF and the RAPW” (by Kitaoka).

Not one of these lectures was continued to the end owing to the interference of the police.

The second series of lectures dealt with Soviet culture. These were: “The process of development and growth of proletarian literature in the U.S.S.R.” (Kitaoka); “Soviet Cinema Art” (Matsudzaka); “The reality of Soviet Cinematography” (Fukuro Innei); “The Soviet theatre” (Kumodzava). All the lecturers mentioned are members of the NAPF.

Besides these lectures the members of the section have published many works (essays, articles and shorter items) on various problems of the theory of Art and literature in “Proletarian Science,” organ of the Institute. There were 23 of them published during the past year. Among them were: “The Japanese proletarian literary movement in 1926” (Jamada); “The present problems of the proletarian Drama” (Sugimoto); “Literature, art and language” (Kurahara); “Left flank rationalisation of the social-democratic literature” (Kitaoka); “The antiproletarian character of the Literary front group” (Komia); “A critical view of the social-democratic literature” (Nagai); “Maiakovski’s funeral” (Sugimoto) etc.

In the work of the sections, covering a period of a year, numerous defects were noticed, and steps were taken to rectify them. One of the principal of these lay in the insufficient organization of the given problems. In most eases the articles, appearing in “Proletarian Art,” were in no way connected with the study of the problems under discussion in the section itself. The discussion of problems at public meetings of the different subsections was often dull, even though at their private meetings the same problems provoked a very lively discussion. Up to now 22 themes have been fixed for study during 1931. Among these are: “Historical study of Japanese proletarian literature” (Jamada); “Theory of proletarian cinematography” (Ivadzaki); “Theory of proletarian plastic arts” (Okamoto); “History of Soviet theatrical art” (Sugimoto); “Discussion in Soviet literary science” (The Pereverzev and the “Na Postu” group) etc.

The section of Art, Literature and Language is widely developing its publishing activities and in addition to the magazine Proletarian Science the section proposes to make use of the symposiums Art and Marxism published every six months; the “Library of the Theory of proletarian art,” in which the following works will appear in 1931: Kitaoka; “Modern Soviet literature”; Karagut; “Theory of proletarian literature”; Sogimoto: “Problems of proletarian cinematography”; and finally the quarterly magazine Studies in the Sociology of Art.

The subsection of the History of Russian literature has changed its name to Subsection of Soviet Literature, and in 1931 proposes to publish the following works: “Soviet Proletarian Authors’ Series” (14 works of Soviet proletarian authors will be issued at first); Soviet Dramatical Series (in 5 volumes); Marxist History of Art series (translations of works of Soviet Marxists, dealing with the history of Art). The first works to be published in this series are Fritche’s History of European literature, History of Russian Art etc.

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1931-n02-LWR.pdf