Patterson reports on the meaning of the Profintern’s Fifth International Congress for Black workers.

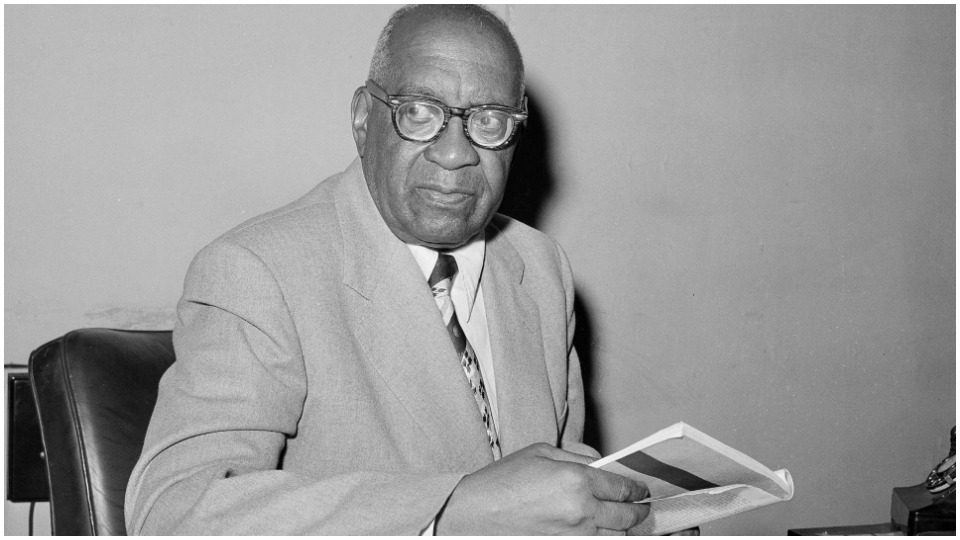

‘The Fifth Congress of the R.I.L.U. and the Black Colonial Masses’ by William Wilson (William L. Patterson) from Negro Worker. Vol. 3 No. 11. November 1, 1930.

The Vth Congress of the Red International of Labour Unions met at a moment of tremendous international importance. The great economic crisis of the capitalist world reflected itself in a series of extremely disastrous panics on the stock exchanges in the great financial centers, in numerous bankruptcies of “reliable” business houses, in the complete closing down of many industrial plants and the operation of others on a part time basis, the ruination of tens of thousands of “comfortably fixed” middle class people, mass unemployment, reduced wages, the lengthening of the working day and general worsening of the living conditions of the working class. The industrial crisis is enormously aggravated by the great agrarian crisis with it tremendous drop in the prices of agricultural products which resulted in terribly increasing the misery of the colonial peoples. The relations between the ruling class and the exploited and oppressed masses was changing. Nowhere was this more clearly to be seen then in the colonial world where the millions of colored toilers of many races and nations existed under conditions of extreme poverty and unhuman exploitation. Here the full weight of the crisis was felt. Here the offensive of the strickened bourgeoisie was most intense and the defensive power of the exploited masses weakest, but here too, the revolutionary temper of the masses flamed high.

The revolutionary upsurge of these oppressed masses had reached in many places the stage of armed conflicts in Chins; it was expressing itself in numerous economic and political struggles in India, and in a series of spontaneous revolutionary outburst in Africa.

The ruling class was confronted with conditions which made it an absolute impossibility to go on ruling in the same old manner as before. The mask of democracy with which it had cloaked its savage dictatorship had to be thrown aside. The “white man’s burden” was shown to be the blotted money-bags filled with the loot stolen from the native masses. Boot and spurred he sat upon the backs of the miserably degraded colonials whose efforts to free themselves from the ever-increasing burden of taxation and slavery were now and then drowned in blood, under the direct guidance or full support of the leaders of the “Labour” and “Socialist” parties. This in brief was the picture of the world situation which filled the eyes of the 571 representatives of the 17 million of fighters who have enlisted under the revolutionary banners of the R.I.L.U. This was the picture which for the first time was presented without any attempt at veiling its horrors, of lynching, pass laws, poll tax, head tax, forced labor and slavery to an international delegation of Negro workers’ representatives and the black representatives of the toiling masses of Africa. The representation of the Negro masses was international,–from Africa, from the United States, from the Carribes and from South America, it had been elected by the toiling masses themselves

There was only one place in the world where such a picture could have been shown: a country free from the terrors of the capitalist economic and agrarian crisis, free from the dangers of political strikes, of mob violence and white terror, a country where hundreds of once oppressed nationalities now stand together in a free federated union of Soviet Republics; a country where the working class is master of all that it produces and all that it surveys, a liberated working class linked in an indissoluble alliance with the poor and middle peasants; a country free from all save the threat of war by the imperialist powers.

One of the important questions discussed at the Congress was the linking up of the proletarian struggle in the metropolitan centers with the struggles against imperialism in the colonies. The weakness of the proletariat in the ranks of colonial and semi-colonial countries was exhaustively analysed; the methods to be employed to secure proletarian hegemony in the colonial movement and to utilise this as a unifying contact tact between them and the fighters for the proletarian revolution and dictatorship in capitalist countries was outlined.

For the first time the representatives of the exploited millions of Black Africa saw their revolutionary liberation struggles posed in correct relation with the proletarian revolutionary struggles in capitalist countries. Certainly the liberation struggles of the Negro peoples had always been an inseparable part of the world revolutionary movement against imperialism but the isolation of the African peoples, their unfortunate lack of direct contact with the European revolutionary movement or with the revolutionary struggles of the Chinese and Indian peoples had deprived them of the benefits of the knowledge of the experiences gained in these struggles.

For the first time the representatives of the proletarian masses of the “mother” countries came face to face with those who could describe in detail the concrete struggles of the African colonials against imperialism. The struggles of these peoples lost much of its “abstractness”, the underestimation of the importance of the struggles of the Negro peoples to the world revolutionary struggles was dealt a smashing blow. The imperialist utilisation of the exploitation of the black peoples to undermine the standard of living of the “home” workers and consequently to intensify the degree of their exploitation and oppression was clearly drawn. The use of these natives peoples for purposes of imperialist wars was unfolded.

For the first time representatives, of the masses of black Africa saw a world advancing toward socialism; saw a freed working class, an emancipated peasantry linked together in a common struggle to construct a new world on the ruins of the world of capitalist exploitation and oppression which had been theirs before. This could not fail to have great effect upon them all. Nor was it unexpected when these African delegates one after, another pledged the support of those whom they represented to the toilers of the Soviet Union; pledged their support for unity of struggle with the enslaved wage workers of the metropolitan areas, pledged their support of the struggle against the coming armed attack upon the Soviet Republics. A concrete and tangible program was formulated. The revolutionary trade union movement pledged itself to support the struggle for the emancipation of the colonies in a real and serious manner. The establishing of closer contacts between the workers of the imperialist countries and those of the colonies was a leading plank in the program.

The entire world revolutionary movement must hold each and every section of that movement to the letter of that piece. The workers of the black colonies still to a large extent regard the workers of the imperialist countries as part and parcel of the machinery of exploitation. These white workers have many a time participated in the lynching mobs, in the attacks perpetrated upon the black and colonial peoples, therefore the fears of these toilers are not unnatural. To overcome this mistrust, the unity of all the exploited and the oppressed must be strengthened for this unity alone can bring the victory over the exploiters and oppressors. Long live the revolutionary solidarity of workers of the capitalist countries and of the colonies!

First called The International Negro Workers’ Review and published in 1928, it was renamed The Negro Worker in 1931. Sponsored by the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers (ITUCNW), a part of the Red International of Labor Unions and of the Communist International, its first editor was American Communist James W. Ford and included writers from Africa, the Caribbean, North America, Europe, and South America. Later, Trinidadian George Padmore was editor until his expulsion from the Party in 1934. The Negro Worker ceased publication in 1938. The journal is an important record of Black and Pan-African thought and debate from the 1930s. American writers Claude McKay, Harry Haywood, Langston Hughes, and others contributed.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/negro-worker/files/1930-v3-special-number-nov-1st.pdf