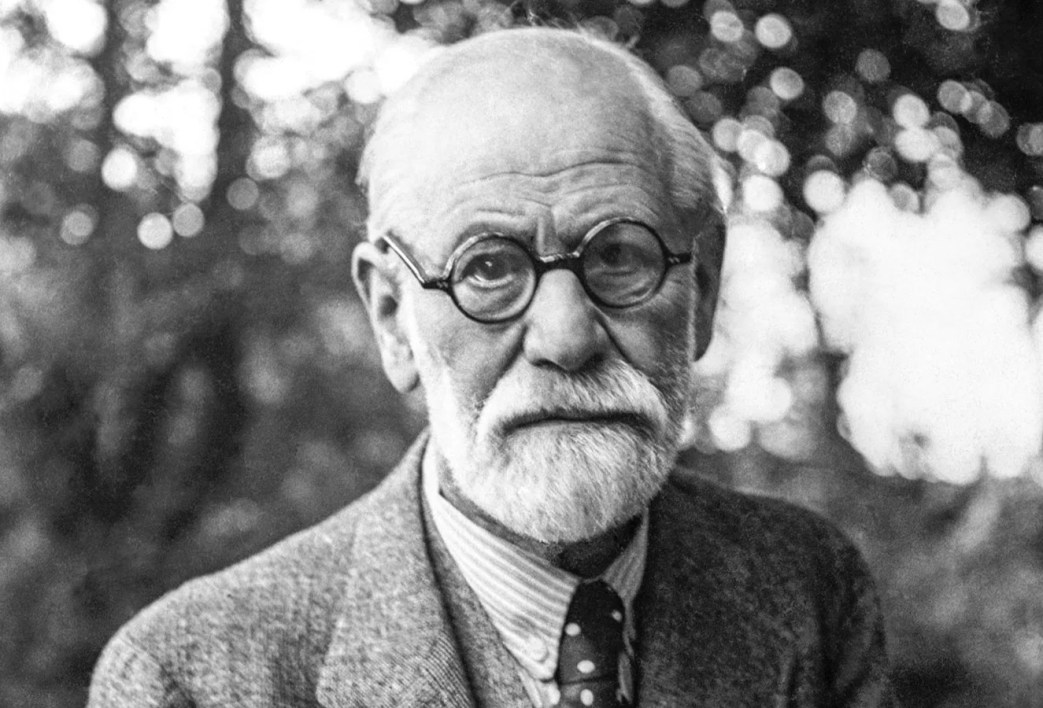

This rare English translation from Frtische sharply criticizes Freud’s approach to art. Fritsche, who died in 1929, was an early Russian Marxist literary critic who played a large and important, if somewhat controversial, role in the world of Soviet literature in its first decade. A leading figure in the Commissariat of Education, Fritsche was the first editor of Literature and Marxism.

‘Freudism and Art’ (1925) by Vladimir Fritsche from Literature of the World Revolution. No. 5. 1931.

In his article, “Freudism and Marxism.” published in the periodical “Pod Znamenem Marksisma” (Under the Banner of Marxism) C. Iurenets pointed but quite justly that it was no accident that Freudism originated in Austria-Hungary.

“Freudism was born in Vienna and Budapest, in a country which lies in the border land of the history of capitalism and which has not been “nourished by the traditions of the heroic epoch of capitalism. Its bourgeoisie has, without making any great efforts, prospered on the backs of the Croatian, Slovenian, Dalmatian and Serbian peasants, who have had their marrows sucked dry Freudism absorbed a great deal of the spirit of that capitalism.”

Futher on C. Iurenets offers a characterization of the spiritual culture of Austria, especially of Vienna, which in some of its peculiar features reflects the special position, the special character of Austrian capitalism.

If we reconstruct somewhat this characterization, if we omit some points, not essential for us at the present moment, and more sharply stress some others sketched in his article, then we may say that the most salient traits in the Weltanschauung of the Viennese bourgeois intelligentsia are: 1) eroticism, 2) estheticism, 3) individualism,—traits proper to every bourgeoisie and to every bourgeois intelligentsia which “prospers” in society “without special efforts.” We may be permitted to illustrate this world-outlook by a few passing examples.

First of all, eroticism.

It was in Vienna that O. Weininger lived and wrote. He wrote “Sex and Character” that was quite a sensation in its time. Here flourished a host of similar writers, working on analogous themes and publishing bulky “investigations,” for example on the “Three Degrees of Eroticism” (Liska). Here, in Vienna, was resurrected an image of the feudal epoch, which seemed to have passed away forever,—Don Juan in Wassermann’s novel, “Masks of Ervin Reiner.” Here in Vienna was the second fatherland of an other erotic type, that XVIII century adventurer, Casanova. His memoirs were published there in luxurious and popular editions, and his image came to life again in the poetry of Schnitzler and Hofmannsthal.

Side by side with eroticism, estheticism.

The Viennese bourgeois intelligentsia is always eager in search of new esthetic sensations. As personified by Herr Bara, he burrows through out the world and popularizes the decadents, then impressionism, then expressionism. He approaches life with an esthetic measuring-stick.

Life for him is either play,—(“all life’s a play, he who has comprehended that is wise,” says the magician Paracelsus in Schnitzler), or in a dream, as in the play of old Grilparzer, “Marriage of Sobeida.” Art, for him, is a self-sufficient realm, elevated above life—“art for art’s”—as in Hofmannsthal’s play, “Titian’s Death.” The artist stands like a sorcerer above life, apart from life.

And, finally, individualism.

It will be sufficient to point out that in Austrian-Viennese literature, social problems are extremely rare and fortuitous and are always overshadowed by the motive of the sovereign personality, which is often Solitary, sometimes unsocial.

All these traits, so characteristic of the Viennese bourgeois intelligentsia, appear plainly also in the teachings of the Viennese school of art.

Although it aims at applying the psycho-analytic method to the interpretation of the phenomena of artistic creation, Freud’s school, however, has by no means subjected all forms of art to analysis. Neither music nor architecture—arts predominantly formal and “contentless”—naturally have not entered their field of vision. As for painting, their chief contribution is Freud’s work on Leonardo da Vinci. They have devoted more attention to poetic creation.

“Poetic productions, more than any other artistic productions, are subject to psychological analysis” (Rank and Sax: “Significance of PsychoAnalysis in the Science of Mind”).

In this field one is especially struck by the voluminous work of O. Rank, who has investigated layers of world literature, significant from his point-of-view, from hoary antiquity to our own times, especially in great work: “The Incest-Motive in Saga and Poetry”, and likewise in his articles on “Myth and Fairy-Tale” and “Double-gangers” (in the anthology “Psycho-analitische Beitrage zur Mythenforschung”). Here belongs likewise Neufeld’s book on Dostoievsky. Here are mentioned those works of the Viennese school in which a number of poems are illuminated and explained from the viewpoint of psycho-analysis.

The erotic foundation of the Weltanschauung of the Viennese school is plainly expressed in its explanation of the origin and essence of the from the viewpoint of psycho-analysis.

According to their opinion, art made its appearance together with culture. Culture begins from the moment when marriage between near relatives, such as son with mother or brother with sister, and as a complement to that enmity of son to father and brother to brothers—was recognized to be incestuous or criminal, from the moment that this form of marriage and the complexity of feelings connected with it were removed from ordinary life by methods of coercion, and consequently thrust into the subconscious, and finding an outlet first in religious creativeness, then in poetic.

Rank has the floor:

“The beginning of genuine culture must be related sociologically to the moment when certain barriers are set up against incest. From that moment these primitive instincts, with all the complexes of feelings connected with them, are subjected to repression and there begins at the same time the striving of the imagination, reflected over and over again in myth, religion and poetry, to fulfil these infantile wishes, which even now so strongly resist repression that they lead to neurosis, crime or perversion, unless there is an especially favorable predisposition to sublimate these experiences in the form of artistic creation.”

Thus, in the distant past, artistic creation and art became possible only thanks to the presence of two conditions: on the one hand, of certain sexual cravings, recognized as incestuous and as such repressed from life and consciousness; on the other hand, of a special gift for reworking in a certain way in the imagination these cravings which were repressed into the subconscious, for sublimating them. Thus, art grows up, at the dawning of its life, from the sex principle, apart from which, apparently, it would have been impossible.

Such an assertion contradicts all we know of art on the lower levels of human culture. Ethnologists and investigators of pre-historical archaeology indicate with remarkable unanimity that among the tribes of hunters, whether palaeolithic or contemporary, neither music, nor plastic arts, nor poetry has, in its first stages, any relation to the sexual factor. Grosse asserts this categorically as regards music, Hoernes, as regards the Plastic arts.

Art is content artistically formed. It is absolutely clear that before this or that experience, even sexual, could receive form by artistic means it was necessary for the feeling for form to have been crystallized in the psyche of primitive man, and that feeling for form—the quintessence of art—arose, beyond a doubt, in the labor process, as a by-product of the rhythm of work.

How the primitive hunter of palaeolithic times became an artist of the plastic arts has been splendidly shown by Fairburne in one of his articles:

“The adaptation of a long splinter of flint, by means of oblique blows directed upon it, was bound, after arousing the feeling of form, to arouse a desire to impart greater regularity to the separate hollows. Hence, the creation of a rhythmical disposition. Like every other regularity, this rhythm was bound to be easily stamped on the memory. The developing feeling of form very rapidly heightened this rhythmical disposition into an ideal which was there for the hunter whenever he was working stone, and it was soon transferred to the working of bone.”

Thus, in the process of labor was born the plastic form (first, in the form of geometrical and linear ornament) just as from the rhythms of work, as Bucher showed, arose the musical and poetic form. And just as at the dawning of its life artistic form in no degree owes its origin to sexual feeling, so that which took form in this stage of development, that is, content, also had no relation to the sexual factor, for the content of art of the hunting peoples, both in the palaeolithic age and today—whether it is a hunter of the Madlen epoch or a Bushman of today—is first of all not sexual feeling, but hunting and the experiences connected with that.

If the artistic act presupposes, as the Viennese school teaches, the repression of certain sexual feelings, recognized as incestuous, then, from this point-of-view, how shall the art of the palaeolithic hunter—those splendid representations of deer, mammoths, bison, etc.—be explained?

When the hunter of the Madlen epoch drew these images on the walls of caves or on bone, did he have to sublimate certain “incestuous” sexual cravings? May these animals be regarded as representations of totems? As is well-known, a totem-group used to select one beast or another as pro-patron, but according to the teaching of the Viennese school the totem is nothing other than the sublimated father, that father who used to be killed by his sons and whom later, at a higher stage of culture, as a sign of tardy repentance, it was forbidden to kill (Freud, “Totem and Taboo”). However, such an interpretation is contradicted by the fact that some of these animals are pictured wounded in the side by an arrow or dying from a wound, whereas it was regarded as a sin to kill a totem.

In the same way, from the viewpoint of the Viennese school one can neither understand nor explain the ornamental art of the following period in the development of humanity: the ornamental style is the style of primitive agrarian communism, when, evidently, matriarchate was supreme, when, consequently, that complex of feelings which the Viennese school regards as the fundamental and principal- material of artistic creativeness had not yet been repressed from life and consciousness into the subconscious, when, consequently, if the latter’s position is correct, there could have been no art at all. However, artistic creation at this stage too is to be seen.

On the highest stages of culture the artist, according to the Viennese school, in no way differs from the artist of hoary antiquity.

There are three types of psychic organizations.

The normal person in the period of sexual maturity represses the sexual attachment for the mother, which is proper to every child, accompanied by enmity for the father and brothers (or attachment for the father accompanied by enmity for the mother and sisters) into the subconscious. There these cravings, henceforward unnatural and pernicious, slumber peacefully, without violating the equilibrium of the organism, for some sort of Kind sentinel or censor stands at the threshold of consciousness, refusing them admittance. And only in sleep, when the censorship of consciousness is weakened, do these cravings come to life in confused or brilliant phantasies of dreaming, which, however, are immediately forgotten when the man awakens. The second type is the neurotic.

In him these repressed cravings of the infantile period break into consciousness, become real, enter into conflict with reality, provoke the need for different kinds of self-defense against them, lead to psychical trauma, to neurosis.

The third type is the artist.

The cravings of the infantile period, which work in his subconsciousness, provoke from him efforts to repress them, and these efforts in some marvelous manner pass them over into the sphere of the imagination in the form of symbols, so that the artist without suffering eliminates these cravings by overcoming them in imagination, not in real life.

Rank has the floor:

“Artistic creativeness is a solution of the conflict which allows the individual, while avoiding real incest, to be saved from neurosis and perversion.”

Or in another place:

“The artist, who is forced to exert intense repression, overcomes his strong instincts in imagination, just as primitive humanity, in the primitive repression of those same cravings, became freed from them by transferring them from reality into myth and religion.”

Thus, the artist who is in the power of infantile (and at the same time, pre-historic) cravings represents, in Rank’s words:

“Despite his high intellectual ability of sublimation as regards affects as well as in essence (ontogenetically) and also from the viewpoint of the progress of the human race (philogenetically), a throwback, a halt at the infantile stage.”

That is how the Viennese school represents every artist and every writer.

Freud does not merely claim that Leonardo da Vinci became an artist at the very time when, by forcibly repressing his sexual attachment for his mother, he eliminated it in imagination by creating his first artistic experiments, the heads of laughing women (that is, his mother). According to Freud there was a long decline in his artistic giftendess (which, by the way, contradicts facts known to us) and he again came to life as an artist when he was some fifty odd years old, precisely because at that time he was invited to paint the portrait of Monna Lisa and at the sight of her again became subjected to his subconscious craving for his mother (Monna Lisa is the artist’s mother). Freud goes further, he tries to prove that the very artistic act was for Leonardo, an asexual person who had absolutely repressed all sexuality into his subconscious, nothing other than the sexual act itself. His “real sexual life” says Freud, was reflected, in his creative activity, with its passing from passion to calm and pauses. Neufeld pictures Dostoievski as such an “eternal child,” sublimating in his artistic productions the incest (Oedipus) complex; his patricidal cravings he embodied not only in the brothers Karamazov, but also in Raskolnikov, in which case the father is replaced by the old hag of a usuress.

In his “Incest Motive in Poetry,” Rank has collected a vast mass of material from all the literature of the world, from Ancient Greece to our own times, in confirmation of his thesis that European poets of all times and nations, in their productions have done nothing at bottom except to emancipate themselves by the help of imagination from the incest or Oedipus complex.

There can be no quarrel as to the motive of love of the son for his mother, of enmity of brothers for each other, of enmity of son for his father, in fact extremely often forming the content of these productions. But, firstly, this incest complex is far from exhausting, as far as subject is concerned, the entire wealth of poetry and even less the entire wealth of the plastic arts of European humanity. And, secondly, it is beyond dispute, likewise, that the Viennese school often sexualizes in a tendentious manner various literary images and also the creator of these images, for, according to their teachings, a poet may reflect in his productions only himself, only his own desires.

One example is sufficient.

Shakespeare’s Hamlet is of course not a very clear figure, but yet a certain amount of agreement regarding him does exist. Hamlet represents for us first of all, an intellectual nature, comparatively unerotic, while the duty which was incumbent on him overshadowed all in his soul and finally he loves his father with a tender and inspired love.

Rank offers us a different Hamlet.

Hamlet is a sexual type, he is sexually attached to his mother; if he loves his father, it is only in so far as in his subconscious the consciousness of enmity to him and a desire to do away with him are at work. He learns that his father is murdered, and his desire is fulfilled. According to the principle of blood-revenge he must take vengeance on the assassin, he must kill his uncle, but he is not capable of it. He may slay Polonius (according to the play, he thought it was his uncle), he may despatch to the other world Rosencrantz and Gilderstern, but not his uncle. Why?—Because he does not consider himself entitled to kill a man for that which he himself wanted to do (in his subconscious). His melancholy comes from his sexualness, from his attachment for his mother, from his unconscious enmity for his father, from the impossibility of killing his uncle for that which he himself had wanted to do. The Hamlet with his doubts has disappeared, with his waverings between religion and pantheism, with his hatred for the base world of the court,—there is left an erotic, the victim of an Oedipus complex, the Viennese Hamlet of the XX century.

And, for the sake of a parallel, here is an analogy from the artistic workshop of a Viennese poet.

The myth of Oedipus undoubtedly contains an echo of that hoary antiquity (the age of the matriarchate) when the son could marry his mother and set aside his father, but the myth itself took form in the age of the patriarchate, when such phenomena and feelings had been recognized as pernicious and, therefore, in the myth the hero is overcome by Fate’s punishment. Sophocles made use of this old myth merely in order to give the Athenian democracy a lesson on the necessity of obedience to the civil and moral laws of the city-state. In any case, in his interpretation Oedipus is anything but an erotic type. His marriage to his mother is left in the shade. The Viennese poet Hofmannsthal limns another Oedipus—depicted in strong sexual colors, and his play (Oedipus and the Sphinx) culminates in a scene of passionate love-declaration between son and mother, who, it is true, do not know who they are, though that is perfectly well known to the spectator, it stands to reason.

Both of these images—Rank’s Hamlet and Hofmannsthal’s Oedipus—issued from one and the same Viennese workshop.

The excessive preoccupation of the Viennese school with the sexual factor is nowhere so plainly expressed as in its interpretation of the psychology of the tyrannicide.

It is well known that in general the Viennese school sees in mass political movements nothing other than expressions of the libidinous cravings of the infantile and pre-historic periods. This is no place to deal which this question which has been explained by Freud in his “Mass Psychology” and by Rank in the same spirit in his article, “Myth and Fairy-Tale.”

In this we are concerned with the political declarations of these writers and literary productions dealing with the theme of regicide.

Every revolt against the monarch is nothing other than a certain transformed phenomenon of enmity of son for father, which at bottom has its root in the sexual factor of the mother-fixation.

If Dostoievski entered the circle of the Petrashevski, it was because in his subconscious he was moved by a yearning for patricide, which formed the leitmotiv of all his artistic works. In his study of Dostoievski Neufeld says:

“An attempt on the life of the tsar was patricide, to which the writer was urged unconsciously by an incestuous attachment”2

If Shakespeare creates his play “Julius Caesar,” it, too, like “Hamlet,” is nothing but an artistic projection of his own patricidal cravings. However, granted a rather sharp censorship of consciousness, at a certain stage of culture these cravings came to be regarded as incestuous and criminal, and the artist is compelled to deform them in some way and veil them over; that is why Hamlet consciously loves his father and murders not his father, but his uncle and step-father, that is, a dummy-father.

Julius Caesar is merely another variation of Hamlet.

Rank cannot help confessing that Shakespeare’s Roman drama is, properly speaking, a political tragedy, “a drama of men,” in which there is not one word on love, in which there is neither father nor mother. Nevertheless, he asserts:

“The tragedy represents a classic example of poetry, which, while not containing any references to sex, nevertheless draws its moving forces in infantile, unconscious sexual impressions.”

Brutus, who rebels against Caesar, is the poet who in imagination frees himself of his enmity to his father. Cassius, who is consumed by the thought of suicide, is that same poet who beforehand kills himself for that criminal enmity. If on the eve of battle Brutus is confronted by Caesar’s ghost, that is the same as the father’s shade which rises up before Hamlet. Both warriors, Brutus and Cassius, fall, not by the hand of the enemy, but by their own sword,—they both kill themselves voluntarily because of their rebellion against their father. If such is the case it may appear strange why the poet, when he took as the basis of his political tragedy the biography of Brutus written by Plutarch, did not make use of the detail offered by Brutus, that Brutus was Caesar’s illegitimate son. Why, he should have seized upon this detail with both hands; by hiding behind it, he could have deceived the watchfulness of the censor of his consciousness and more plainly have put on the stage his own patricidal cravings. However, explains Rank, a work of art is artistic precisely because the poet does not say everything he wanted to and had to.

But when the question is put as to why, two hundred years later, another poet, the Italian Alfieri, made Brutus precisely the illegitimate son of Ceasar, who killed in Ceasar both father and monarch, the reason for this is absolutely plain and has no relation to the sexual factor; the fighter for political liberty could not have better been covered with glory than by forcing him, in the name of an ideal, to sacrifice even his beloved father, just as another hero of the same poet (Brutus the Elder) sacrifices his monarchist sons in the name of his political ideal, the republic. Then why did Shakespeare leave out this detail? That is perfectly simple. Shakespeare was a monarchist, and if he, who always and in everything glorified the monarch’s power (for which there were historical causes) nevertheless depicted in his “men’s” drama a rebellion against the monarch, that is because the play was nothing other than the rebellion, artistically depicted, of Essex and his friends against the English Ceasar—but this Ceasar was not a monarch, not a sublimated father, but a woman Queen Elizabeth.

In the interpretation of the Viennese school a sexual significance is imparted, not only to motives and images such as the warrior for political liberty, but to every other sort of concept and symbol with which the artist of writer works, and in this they often fall into shrieking contradictions. One instance:

In his Study of Leonardo da Vinci Freud says: “In the complex connected with father and mother we see the root of religious needs: the omnipotent god and beneficent nature appear to us the greatest sublimation of father and mother.”

Thus, according to Freud, the father is sublimated in the form of god (religion, the church, the authority of religion and the church), while the mother is sublimated in the form of the opposite of all these concepts, in the pas of nature (scientific investigation, scientific and artistic naturalism).

Taking this thesis as his point of departure, Freud goes on to prove that Leonardo, who spent his childhood fatherless, as an illegitimate son growing up without a father’s authority, in consequence was not religious, did not obey religious and ecclesiastic authority, but, since from childhood had a fixation for his mother, his mother became transformed for him into nature which he studied with devotion and enthusiasm both as artist and as scientist.

Thus, we are supposed to believe that at all times, in all countries, the father is always sublimated in the form of religious-ecclesiastical authority, but the mother in no case. On this subject Neufeld holds a different opinion. Pointing out that toward the beginning of the seventies Dostoievski had freed his psyche of the obtrusive, subconscious cravings for incest by sublimating them in the form of artistic images, Neufeld gives a characterization of the writer as a publicist, and once we are talking, not of artistic creation, but of political ideas, it would seem that here at least there would be no sexual lining,—but no!

“The eternal melody of Oedipus is audible even in such a remote sphere. Love for Mother-Earth, for Russia, veneration of the order ordained by god-father-tsar, devotion to Mother Church, the Orthodox Church, this melody sounds forth in many variations.”

Thus Leonardo sublimated his father in the form or religious and ecclesiastical authority, but Dostoievski, just the opposite, his mother. Whether the reason for this difference has its root in the fact that in the first case we have an Italian artist of the XV century, and in the second case a Russian writer of the XIX century, or in something else, Freudism gives no answer.

Besides eroticism, in the teachings of the Viennese school on art, another trait, characteristic for the Viennese bourgeois intelligentsia of the era of decadence comes to the fore,—estheticism.

While the followers of Darwin, who likewise deduced the source of art from the sexual instinct, saw in it a phenomenon highly useful, not only in a biological sense but in the social sense, as a means for bringing the sexes together, it has lost all serious social significance in the interpretation of the Viennese school. The primitive savage singing an erotic song or staging an erotic dance,—similar erotic art is to be found, of course among tribes at a low stage of development, but is not the beginning of art,—was a social being, for the instinct of race and the instinct of the collectivity spoke in him.

The artist, as he appears to the Viennese school, is a being essentially unsocial. Wracked by subconscious desires, he sublimates these individual wishes of his in artistic images. Art, for him, is merely a means for restoring the equilibrium of his organism. Essentially he is just as unsocial as the neurotic. It is true that insomuch as, in distinction to the neurotic, he creates a work of art which others may also enjoy, he accomplishes involuntarily and indirectly a social work, but the social significance of this work created by him is minimal. Just as the artist himself in am absolutely individual way, eliminates his incestuous feelings in imaginative images, the spectator of a play or the reader of a novel, in just as individual a way, again experiences the cravings of the infantile and prehistorical period which have grown dull in him, as a normal type. In this, art does not serve as a means for welding and uniting people, it does not form means of organizing individual consciousness and social life. Its only social function amounts to rendering somewhat less pernicious certain feelings harmful to culture, which, moreover, as we shall see below, from the viewpoint of that school, become more and more atrophied with the growth of culture.

Art is an esthetic play, art for art’s sake. In our society it is a vestige of the past, not only because in essence it is the incarnation of the experiences of the infantile and pre-historical world, but also because in it alone we find, at our stage of development, the faith, native to the people of hoary antiquity, of the period of animism, in man’s omnipotent thought. In it there is an element of magic.3 This faith in the omnipotence of its thought is later, in the progress from animism to religion, in part renounced in favor of gods, says Freud (“Totem and Taboo”) but now, when science is supreme, mankind, “filled with self-renunciation,” has submitted to reality, “acknowledging its weakness.”

“And only in one sphere has the omnipotence of thought been preserved in our culture, in the sphere of art. In art alone does it still occur that man, wracked by desires, creates something similar to their satisfaction and that this play, thanks to the artistic illusion, awakens affects as if it represented something real.”

But this is not that socially utilitarian magic which was created by the paleolithic hunter when he drew images of animals and thus subordinated nature and life to his hunting-group, not that magic which was accomplished by the neolithic agriculturalist when she modelled a vessel and decorated it with a pattern, to the sound of her song, while both the ornament and song were intended to guarantee the soundness of her household; in the interpretation of the Viennese school, art is purely individual magic and play, deprived of social significance, an esthetic illusion of experiencing instincts and wishes unnecessary culturally and even harmful.

Side by side with eroticism, in the teaching of the Viennese school om art, its absolutely individualistic approach to it comes into relief.

It thinks of the artist as a self-sufficient personality, whose creative work is not determined by any external factors.

It is only on the lowest stages of culture, in which collective creation prevails, that it is conditioned by external, even economic and social causes,—so much of a concession Rank is forced to make under the influence of anthropological research. In pursuing in one interesting article, the transformation of myth into fairy-tale, he cannot help seeing that the fairy-tale proceeded from the myth in a definite economic setting, that is, in a setting of acute material need, for only by taking into account this circumstance can we understand why the fairy-tale so often talks of poverty, of material deprivations, while side by side with this there reigns in it a naive rapture with “super-wealth, super-grandeur, super-power, knowing no limits”. Ii analyting several fairy-tales, Rank further comes to the conclusion that the fairy-tale was born from the myth, not only in a setting of “crushing material need,” but at a certain stage of social development, namely when the rule of the father (the horde of hunters) gave way to the “union of brothers” (matriarchate).

“The fairy-tale represents that stage of culture at which the rule of the father gave way to competition between brothers…The fairy-tale which grows up out of these conflicts and this struggle makes use, for their representation, of the traditional mythical forms of the patriarchal period but now on a different social and cultural level.”

One step more and we should have a sociological interpretation of the passage of fairy-tale into myth; and Rank is ready to take this step, but not in the text, but in a foot-note, in which he declares, though quite unconfidently, that “the psychic factor” which gave birth to the fairy-tale “seems to have its parallel in the fact of communal ownership of mother earth during the era of the passage of the primitive European tribes from hunting and herding to sedentary agriculture.”

But, firstly, that only “seems” so, and, secondly, there is merely a certain “parallel”, and finally, primacy belongs obviously to the “psychic factor” which gave birth to the fairy-tale and not to the material factor of the replacement of one economic form by another.4

But what is to a certain degree acknowledged on the lower stages of culture is denied at its heights.

In “cultured” society the artist is a self-sufficient personality, subject to no external influences, while his productions are, in Rank’s expression, “personally, individually conditioned phenomena of his own peculiar spiritual life.”

In order to comprehend the creation of an artist there is no need to know either the epoch in which he lived, or his environment. For Freud, Leonardo da Vinci is not a Florentine artist of the XV century, but merely the illegitimate son of a lawyer and a peasant woman, who spent his childhood without knowing paternal authority. From this one circumstance, which could have occurred in any country and epoch you like, he deduces all his creative activity, both artistic and scientific, i.e., his veneration for nature, his naturalism and his scientific approach to art, whereas all these traits are characteristic of the majority of typically Florentine artists (see Berenson, “Florentine Artists”), who were of course not illegitimate children, but all of whom, like Leonardo, were nourished upon the spirit of Florentine bourgeois culture of the XV century,—a culture intellectual, realistic, scientific, irreligious,—which, translated into the language of artistic creativeness, gave us the Florentine naturalistic artist.

In tearing the artist and writer away from their historical environment which predetermined their creative activity, the Viennese school is at the same time powerless to explain the varied and peculiar appearance of the same psychical predisposition. The essential thing is not that Leonardo and Dostoievski were perpetual children gripped by an Oedipus complex, but the question why this complex,—if only it is not a myth,—gave in one case “laughing women’s heads” or the portrait of Monna Lisa or sketches of the most various engines, and in the other case such projections as the Raskolnik family or the brothers Karamazov.

And just as the artist or writer, as a self-sufficient individual, is wrenched out of his historical setting, and, of course, from his class, he is likewise freed from literary tradition.

While collecting a huge amount of material from the literature of the European people to confirm the fact of the “universality of the incest motive among the greatest poets,” Rank at the same time emphasizes that these “constantly recurring images of the poetic imagination” cannot be attributed “to conscious plagiarism or to literary influence.

But still—if we limit ourselves to a single example from the mass of material presented by him—on the one hand, it is strange why in the German literature of the XIX century the “tragedy of fate” flourished, in which the theme of incestuous love was treated in various tones, while this theme afterward disappeared for a long time in the same German literature (in other words, the sexual nature of the poet had changed!); on the other hand there is no doubt that Grillparzer, author of the “Ancestress,” was acquainted with analogous productions of his predecessors, Mulner and Huwald.

In taking its stand on such an individualistic viewpoint, the Viennese school naturally rejects the idea of the historical development of art and literature. If there exists from their point of view a certain development of literature, this consists, not in the social conditioned evolution of literary and artistic styles, genres, forms, but merely in the gradual triumph, as reflected in literary works, of the conscious over the subconscious. To illustrate this process, Rank deals with three plays built, in his opinion, around the same subject, that is, on the Oedipus complex—in Sophocles, the son still kills his father and marries his mother, without knowing who they are (first censorship of consciousness); the Shakespearean Hamlet consciously loves his father, warring with him only in his subconscious, and murders not him, but his step father—stronger censorship of consciousness; Shiller’s Don Carlos wars against his father, not for his mother, but for his step mother—she had been his betrothed—and he does not murder his father, his father executes him (still stronger censorship of consciousness).

It is absolutely plain that this gradual distortion by consciousness of the original pattern of the incest complex forms merely an insignificant part of the evolution of the subject itself and the same time has absolutely no relation to the evolution of form and style.

Moreover, this triumph of consciousness over the subconscious, by Which literary development is exhausted, is itself very problematical. In the last chapter of his work “Incest Motive in Poetry,” Rank has collected considerable material from the modern literature of the West, which proves irrefutably that in it the Oedipus complex is flourishing in its most naked form—the subconscious is again triumphing over consciousness—development has gone backward.

But if we grant that consciousness really triumphs over the subconscious as culture develops, does this not signify that in the future art must die? Rank, himself, makes such a prognosis:

“If the capacity for artistic creation may for a certain length of time survive the process of repressing sexuality without loss for the artistic effect, on the other hand, in view of its being predominantly conditioned by the unconscious, it is unable in the long run to adapt itself to the progress of consciousness. As certain phenomena in our contemporary poetry permit us to surmise, there is a growing feebleness, first of all, in the capacity for artistic creation capable of influencing wide circles and then, evidently, in the capacity to perceive and enjoy works of art.”

The question whether art is possible on a higher stage of consciousness Rank raises in the last pages of his book, while leaving it open however. In restricting the evolution of art and literature to the reflection in it of the triumph of consciousness over the subconscious, the Viennese use reduces the history of art to the succession of individual great artists.

“The history of literary development,” says Rank, “consists in the consequential appearance and personal development of individual great poetic personalities.”

The Viennese school, thus, restores us to the pre-historical period of our science. While we think of the history of art and literature as an impersonal and nameless process, governed by natural law, of literary and artistic development, the Viennese school, faithful to its individualistic position, reduces it as Sainte Beuve once did, to a portrait-gallery of artists and writers.

In setting to one side the problem of the history of art and literature, the Viennese school concerns itself, in Rank’s words, not with the history of art, but with the “psychology of the artists”, but it is incapable of solving the final problem which arises in this sphere, what is meant by artistic giftedness? If the artist, as distinct from the neurotic, by strong repression of his affects sublimates them in the form of images or symbols, then the question remains unsettled:

“Why he is capable at all of curbing these affects by means of art? Why he does not do so like a normal person? Or why is he not compelled to resort to the symptoms of self-defense characteristic of the neurotic? (Rank).

Thus, Freud as well, in finishing his work on Leonardo da Vinci, admits that, if he succeeded in explaining the psycho-analysis of the entire artist, yet “his extraordinary tendency to repress his cravings and his unusual capacity for sublimating them” remained unexplained:

“Here is the last point which psycho-analysis can attain. From this moment it makes way for biology. Both tendency to repression and capacity for sublimation must be attributed to the organic foundations of character upon which the psychical superstructure is afterwards reared.”

In leaving to the historian and sociologist the problem of the development of art, the Viennese school leaves to the biologist the last word in solving the problem of the artist (provided “organic foundation of character” is not rather a metaphysical concept).

We have not touched on all aspects of the teaching of the Viennese school on art. We have not dealt with their conception of the mechanics of artistic creation, their teachings on the origin of the hero, on humor, on the reflection of Narcissism in artistic creation. The works of the Russian Freudians have been left to one side. Our task amounted 1) to showing how certain characteristic traits of the “Weltanschauung” of the Viennese bourgeois intelligentsia have laid a definite imprint on the teachings of the Viennese school on art, and 2) to prove the following theses:

1. In deducing the artistic act, when all is said and done, from the sexual feeling, at times even identifying them, the Viennese school contradicts what we know of the origin of art and of art in early stages of civilization.

2. In regarding the artistic act as a sublimation of the incest complex it makes erotic packages of certain literary images, just as the Viennese poets turn out their heroes in erotic garments.

3. The excessive preoccupation of the Viennese school with the sexual factor has made itself especially obviously felt in their interpretation of the psychology and the image of the regicide.

4. In sexualizing other concepts or symbols with which artists work, they contradict each other downrightly.

5. In their interpretation art is deprived of its character as a principle active in organizing society, and its social significance is reduced to rendering more or less harmless affects which are culturally unnecessary.

6. While admitting the determination of artistic creativeness by external causes on the lower stages of culture, the Viennese school regards the artist on higher levels of culture as free from all social, cultural and literary influences.

7. In examining artists apart from their historical environment, it interprets wrongly their creative work and is absolutely incapable of explaining the peculiarity of their themes and forms.

8. By seeing in the history of art only the succession of great artists, the Viennese school, by that very fact, denies the idea of a science of art as a regular process of development.

9. In dealing, not with the history of art, but the psychology of the artist, it has not divined the ultimate secret of the artist, his capacity for sublimation.

And finally, although we have not spoken of this, it is plain from all that has been said:

10. The entire teaching of the Viennese school about art, as exposed by us here, bears the stamp of an interesting, but obvious, dilettantism.

Notes

1. All quotations in this article are translated from the Russian.

2. The idea of regicide did not play any great role in the Petrashevstki circle, as is well known; “on the other hand Neufeld asserts that Dostoievski was driven to patricide not only by incestuous attachment,” but also by “his father’s miserliness,” a motive which obviously has nothing in common with the Oedipus complex.

3. Freud confesses that in all probability art pursued tendencies among which “may have been magical purposes as well,” but if art arose as magic (and it actually did), then the entire structure intended to deduce all art from sublimation in the incest complex, crumbles away.

4. Such an idealistic interpretation of evolution fully corresponds to the idealistic sociology laid down by Freud in his “Totem and Taboo.”

Literature of the World Revolution/International Literature was the journal of the International Union of Revolutionary Writers, founded in 1927, that began publishing in the aftermath of 1931’s international conference of revolutionary writers held in Kharkov, Ukraine. Produced in Moscow in Russian, German, English, and French, the name changed to International Literature in 1932. In 1935 and the Popular Front, the Writers for the Defense of Culture became the sponsoring organization. It published until 1945 and hosted the most important Communist writers and critics of the time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/subject/art/literature/international-literature/1931-n05-LWR.pdf