Jugend-Internationale, left-internationalist magazine of the League of Socialist Youth Organisations edited by Willi Münzenberg in Zurich, Switzerland being the war-time home to many exile European revolutionists including Lenin, began a discussion of the ‘disarmament’ slogan engaged in by Swiss, Dutch, and Scandinavian comrades. Lenin intervened in the debate with his usual unusual clarity. The article below written in late 1916 and given this title when it was printed in Jugend-Internationale the following year.

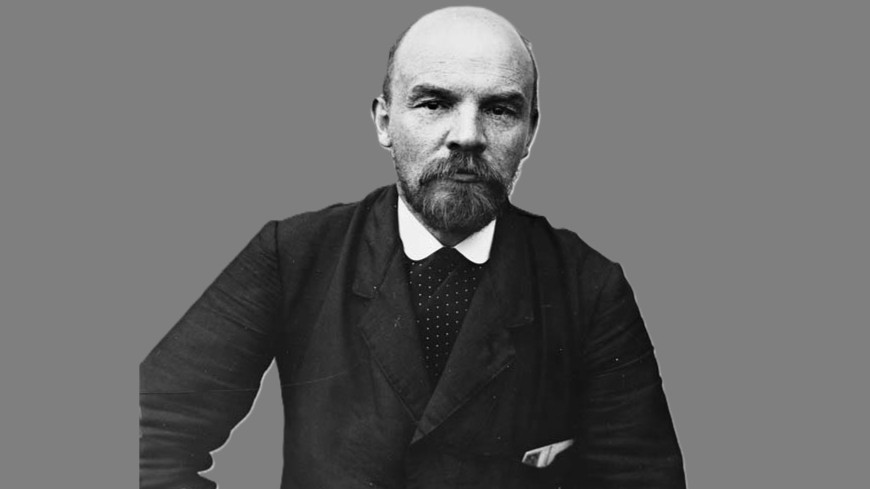

‘The Military Program of the Proletarian Revolution’ (1916) by V.I. Lenin from The Communist. Vol. 14 No. 1. January, 1935.

In Holland, Scandinavia, Switzerland, voices are heard among the revolutionary Social-Democrat—who are combatting the social-chauvinists’ lies about “defense of the fatherland” in the present imperialist war—in favor of substituting for the old item in the Social-Democratic minimum program, “militia, or the arming of the people”, a new one: “disarmament”. The Jugend-Internationale has initiated a discussion on this question and has published in No. 3 an editorial article in favor of disarmament. The theses recently drafted by R. Grimm, we regret to note, also contain a concession to “disarmament” idea. Discussions have been started in the periodicals Neues Leben and Vorbote.

Let us examine the position of the advocates of disarmament.

I.

The basic argument is that the demand for disarmament is the clearest, most decisive, most consistent expression of the struggle against all militarism and against all war.

But it is precisely in this basic argument that the fundamental error of the advocates of disarmament lies. Socialists cannot be opposed to all war without ceasing to be Socialists.

In the first place, Socialists have never been, and can never be, opposed to revolutionary wars. The bourgeoisie of the imperialist “Great Powers” has become reactionary through and through, and we regard the war which this bourgeoisie is now waging as a reactionary slave-owners’ and criminal war. But what about a war against this bourgeoisie? What about a war for liberation, on the part of the colonial peoples, for instance, who are oppressed by and dependent upon this bourgeoisie? In the theses of the “International” group, Section 5, we read: “In the era of this unbridled imperialism there can be no more national wars of any kind”. This is obviously incorrect.

The history of the twentieth century, this century of “unbridled imperialism”, is replete with colonial wars. But the thing we Europeans, the imperialist oppressors of the majority of the peoples of the world, with our habitual, despicable European chauvinism, call “colonial wars” are often national wars, or national uprisings of those oppressed peoples. One of the most fundamental attributes of imperialism is that it hastens the development of capitalism in the most backward countries, and thereby widens and intensifies the struggle against national oppression. That is a fact. It inevitably follows from this that imperialism must frequently give rise to national wars. Junius, who in her pamphlet defended the above quoted “theses”, says that in an imperialist epoch every national war against ore of the imperialist Great Powers leads to the intervention of another imperialist Great Power, which competes with the former, and in this way every national war is converted into an imperialist war. But this argument also is incorrect. This may happen, but it does not always happen. Many colonial wars in the period between 1900 and 1914 did not follow this road. And it would be simply ridiculous, if we declared, for instance, that after the present war, if it ends in the complete exhaustion of all the belligerents, there can be no national progressive, revolutionary wars “of any kind” on the part of, say, China in alliance with India, Persia, Siam, etc., against the Great Powers.

To deny the possibility of any national wars under imperialism is theoretically incorrect, historically obviously erroneous, and practically tantamount to European chauvinism: it amounts to this, that we, who belong to nations that oppress hundreds of millions of people in Europe, Africa, Asia, etc., must tell the oppressed peoples that their war against “our” nations is “impossible”!

Second, civil wars are also wars. One who recognizes the class struggle cannot fail to recognize civil wars, which in every class society represent the natural and, under certain conditions, inevitable continuation, development and intensification of the class struggle. All the great revolutions prove this. To repudiate civil war, or to forget about it, means sinking into extreme opportunism and renouncing the Socialist revolution.

Third, the victory of socialism in one country does not by any means at one stroke eliminate all wars in general. On the contrary, it presupposes such wars. The development of capitalism proceeds very unevenly in the various countries. This cannot be otherwise under the system of commodity production. It inevitably follows from this that socialism cannot be victorious simultaneously in all countries. It will be victorious first in one, or several countries, while the others will for some time remain bourgeois or pre-bourgeois. This must not only create friction, but a direct striving on the part of the bourgeoisie of other countries to crush the victorious proletariat in the socialist State. Under such conditions a war on our part would be a legitimate and just war. It would be a war for socialism, for the liberation of other peoples from the bourgeoisie. Engels was perfectly right when, in his letter to Kautsky, September 12, 1882, he openly admitted the possibility of “wars of defense” on the part of already victorious socialism. What he had in mind was defense of the victorious proletariat against the bourgeoisie of other countries.

Only after we have overthrown, finally vanquished, and expropriated the bourgeoisie of all the world, and not only of one country, will wars become impossible. And from a scientific point of view it would be entirely incorrect and entirely unrevolutionary for us to evade or gloss over the most important thing, namely, that the most difficult task, demanding the greatest amount of fighting on the road to socialism, is to break the resistance of the bourgeoisie. “Social” priests and opportunists are always ready to dream about the future peaceful socialism, but the very thing that distinguishes them from revolutionary Social-Democrats is that they refuse to think over and reflect on stubborn class struggle and class wars that are necessary in order that this beautiful future may be achieved.

We must not allow ourselves to be led astray by words. The term “defense of the fatherland”, for instance, is hateful to many, because the avowed opportunists and the Kautskyists use this term to cover up and gloss over the lies of the bourgeoisie in the present predatory war. This is a fact. It does not follow, however, that we must forget to think about the meaning of political slogans. To recognize the “defense of the fatherland” in the present war means nothing more nor less than recognizing it as a “just” war in the interests of the proletariat, because invasions may occur in any war. But it would be simply foolish to deny “defense of the fatherland” on the part of the oppressed nations in their wars against the imperialist Great Powers, or on the part of a victorious proletariat in its war against some Gallifet of a bourgeois State.

Theoretically it would be thoroughly erroneous to lose sight of the fact that every war is but a continuation of politics by other means, that the present imperialist war is a continuation of the imperialist politics of two groups of Great Powers, and that these politics were generated and fostered by the sum total of the interrelations of an imperialist epoch. But that very epoch must inevitably also generate and foster the politics of struggle against national oppression and the politics of the struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie, and, therefore, also the possibility and the inevitability, first of revolutionary national uprisings and wars, second, of proletarian wars and uprisings against the bourgeoisie, and, third, of a combination of both kinds of revolutionary wars, etc.

II.

To this there must be added the following general considerations:

An oppressed class which does not strive to learn how to use arms, to acquire arms, deserves to be treated like slaves. We cannot forget, unless we become bourgeois pacifists or opportunists, that we are living in a class society, that there is no way out, and there can be no way out, but the class struggle. In every class society, whether it is based on slavery, serfdom, or, as at present, on wage labor, the oppressing class is armed. The modern regular army, and even the modern militia—even in the most democratic bourgeois republics, like Switzerland, for example—represent the bourgeoisie armed against the proletariat. This is such an elementary truth that it is hardly necessary to dwell upon it. Suffice it to recall the use of the army against strikers in all capitalist countries.

The arming of the bourgeoisie against the proletariat is one of the biggest, most fundamental, and most important facts in modern capitalist society. And in the face of this fact, revolutionary Social-Democrats are urged to “demand” “disarmament”! This is tantamount to the complete abandonment of the point of view of the class struggle, to the abandonment of all thought of revolution. Our slogan must be: arming of the proletariat in order to vanquish, to expropriate, and to disarm the bourgeoisie. These are the only possible tactics a revolutionary class can adopt; these tactics follow logically from the whole objective development of capitalist militarism, and are dictated by that development. Only after the proletariat has disarmed the bourgeoisie will it be able, without betraying its world historic mission, to throw all armaments on the scrapheap; the proletariat will undoubtedly do this, but only when this condition has been fulfilled and not before.

If the present war calls forth among the reactionary Christian Socialists, among the whimpering petty bourgeoisie, only horror and fright, only aversion to the use of arms, to bloodshed, death, etc., in general, we must say: capitalist society always was and is an unending horror. And if this most reactionary of all wars is now preparing a horrible end for that society, we have no reason to despair. And in its objective significance, the “demand” for disarmament—or more correctly, the dream of disarmament—at the present time when, as every one can see, the bourgeoisie itself is paving the way for the only legitimate and revolutionary war, namely, civil war against the imperialist bourgeoisie, is nothing but an expression of despair.

We should like to remind those who say that this is a theory divorced from life of two world-historic facts: the role of trusts and the employment of women in factories, on the one hand; and the Paris Commune of 1871 and the December uprising of 1905 in Russia, on the other.

The business of the bourgeoisie is to promote trusts, to drive women and children into the factories, to torture them there, to demoralize them, to condemn them into extreme poverty. We do not “demand” such development. We do not “support” it. We fight against it. But how do we fight? We know that trusts and the employment of women in factories are progressive. We do not want to go back to handicraft, to pre-monopoly capitalism, to domestic drudgery for women. Forward, through trusts, etc., and beyond them to socialism!

This argument, mutatis mutandis, applies also to the present militarization of the people. Today the imperialist bourgeoisie militarizes not only all the people, but also the youth. Tomorrow, it may proceed to militarize the women. In this connection we must say: all the better! The sooner this is done the nearer we shall be to the armed uprising against capitalism. How can Social-Democrats allow themselves to be frightened by the militarization of the youth, etc., unless they have forgotten the example of the Paris Commune? This is not a “theory divorced from life”. It is not a dream, but a fact. It would be really too bad if, notwithstanding all the economic and political facts, Social-Democrats began to doubt that the imperialist epoch and imperialist wars must inevitably bring about a repetition of such facts.

A certain bourgeois observer of the Paris Commune, writing to an English newspaper in May 1871, said: “If the French nation consisted entirely of women, what a terrible nation it would be”! Women and children from the age of thirteen upward fought in the Commune side by side with men. Nor can it be different in the coming battles for the overthrow of the bourgeoisie. The proletarian women will not be passive onlookers while the well-armed bourgeois shoot down the badly armed or unarmed workers. They will take up arms as they did in 1871, and out of the frightened nations of today—or more correctly, out of the present-day labor movement, which is disrupted more by the opportunists than by the governments—there will undoubtedly arise, sooner or later, but with absolute certainty, an international league of “terrible nations” of the revolutionary proletariat.

At the present time, militarization is permeating the whole of social life. Imperialism is the frantic struggle of the Great Powers for the partition and repartition of the world—therefore it must inevitably lead to further militarization in all countries, even in the neutral and small countries. What will the proletarian women do against it? Only curse every war and everything military, only demand disarmament? The women of an oppressed class that is really revolutionary will never agree to such a shameful role. They will say to their sons: “You will soon be big. You will be given a gun. Take it and learn well the art of war. This is necessary for the proletarians, not in order to shoot your brothers, the workers of other countries, as is being done in the present war, and as you are being advised to do by the traitors to socialism, but in order to fight against the bourgeoisie of your own country, to put an end to exploitation, poverty and war, not by means of good intentions, but by a victory over the bourgeoisie and by disarming them.”

If we are to refrain from conducting such propaganda, precisely such propaganda, in connection with the present war, then we had better stop using high-sounding phrases about international revolutionary Social-Democracy, about the Socialist revolution, and about war against war.

III.

The advocates of disarmament oppose the item in the program, “arming of the people” inter alia, because such a demand, they allege, easily leads to concessions, to opportunism. We have examined above the most important point, the relation of disarmament to the class struggle and to social revolution. We will now examine the relation between the demand for disarmament and opportunism. One of the main reasons why this demand is inacceptable is that it, and the illusions created by it, inevitably weaken and devitalize our struggle against opportunism.

Undoubtedly this struggle is the principal immediate problem that confronts the International. A struggle against imperialism that is not intimately linked up with the struggle against opportunism is an idle phrase, or a fraud. One of the main shortcomings of Zimmerwald and Kienthal, one of the main reasons why these embryos of the Third International may possibly end in failure, is that the question of the struggle against opportunism was not even raised openly, much less decided in the sense of proclaiming the necessity of breaking with the opportunists. Opportunism has triumphed—temporarily—in the European labor movement. Two main shades of opportunism have been revealed in all the big countries, first, the avowed cynical, and therefore less dangerous, social-imperialism of Messrs. Plekhanov, Scheidemann, Legien, Albert Thomas and Sembat, Vandervelde, Hyndman, Henderson, et al.; second, a covert, Kautskyist opportunism: Kautsky-Haase and the “Social-Democratic Labor Group” in Germany; Longuet, Pressemane, Mayeras, et al., in France; Ramsay MacDonald and the other leaders of the Independent Labor Party in England; Martov, Chkheidze and others in Russia; Treves and the other so-called Left reformists in Italy.

The avowed opportunism is openly and directly opposed to revolution and to the revolutionary movements and outbursts now beginning, and is in close alliance with the governments, however varied the forms of this alliance may be: from participation in the cabinets to participation in the War Industries Committees (in Russia). The covert opportunists, the Kautskyists, are much more harmful and dangerous to the labor movement because they conceal their advocacy of an alliance with the former under a cloak of euphonious, pseudo-Marxist catch-words and pacifist slogans. The fight against both these forms of predominant opportunism must be conducted in all the realms of proletarian politics: parliamentarism, trade unions, strikes, military affairs, etc. The principal feature that distinguishes both of these forms of predominant opportunism is that they hush up, conceal or treat with an eye to police prohibitions the concrete question as to the relation of the present war to revolution. And this in spite of the fact that before the war the relation of precisely this coming war to the proletarian revolution was mentioned innumerable times, both unofficially, and officially in the Basle Manifesto. The principal defect in the demand for disarmament consists in its evasion of all the concrete questions of revolution. Or do the advocates of disarmament stand for a perfectly new species of unarmed revolution?

To continue. We are by no means opposed to fighting for reforms. We do not wish to ignore the sad possibility that humanity may—if the worst comes to the worst—go through a second imperialist war, if, in spite of the numerous outbursts of mass ferment and mass discontent and in spite of our efforts, revolution does not come out of the present war. We are in favor of a program of reforms which is directed also against the opportunists. The opportunists would be only too glad if we left the struggle for reforms entirely to them, and, saving ourselves by flight from sad reality, sought shelter in the heights about the clouds in some sort of “disarmament”. “Disarmament” means simply running away from unpleasant reality, not fighting against it.

In such a program we would say something like this: “This slogan and the recognition of the defense of the fatherland in the imperialist war of 1914-16 is only a corruption of the labor movement by a bourgeois lie”. Such a concrete reply to concrete questions would be theoretically more correct, much more useful to the proletariat, more unbearable to the opportunists, than the demand for disarmament and the renunciation of “all defense of the father land”! And we might add: “The bourgeoisie of all the imperialist Great Powers—England, France, Germany, Austria, Russia, Italy, Japan, the United States—has become so reactionary and so imbued with the striving for world domination, that any war conducted by the bourgeoisie of those countries can be nothing but reactionary. The proletariat must not only oppose all such wars, but it must also wish for the defeat of ‘its own’ government in such wars, and it must utilize it for a revolutionary uprising, if an uprising to prevent the war proves unsuccessful.”

On the question of militia, we should have said: we are not in favor of a bourgeois militia; we are in favor only of a proletarian militia. Therefore, “not a penny, not a man” not only for the regular army but also for the bourgeois militia, even in countries like the United States, Switzerland, Norway, etc.; the more so that in the freest republican countries (e.g., in Switzerland), the militia is being more and more Prussianized, particularly in 1907 and 1911, and prostituted by being mobilized as troops against strikers. We can demand election of officers by the people, abolition of all kinds of military law, equal rights for foreign and native workers (a point particularly important for those imperialist States which, like Switzerland, more and more blatantly exploit increasing numbers of foreign workers while refusing to grant them rights); further, the right of, say, every hundred inhabitants of a given country to form free associations with free selection of instructors to be paid by the State, etc. Only under such conditions would the proletariat he able to acquire military training really for itself and not for its slave-owners, and the necessity of such training is dictated by the interests of the proletariat. The Russian Revolution showed that every success of the revolutionary movement, even a partial success like the seizure of a city, a factory settlement, a section of the army—inevitably compels the victorious proletariat to carry out just such a program.

Finally, it goes without saying that opportunism cannot be fought by means of programs alone, but only by undeviating efforts to make sure they are carried out. The greatest and fatal error committed by the bankrupt Second International was that its words did not correspond to its deeds, that it acquired the habit of using unscrupulous revolutionary phrases (note the present attitude of Kautsky and Co. to the Basle Manifesto). Disarmament is a social idea, i.e., an idea that springs from a certain social environment and which can affect a certain social environment, and is not merely a cranky notion of an individual. It has evidently sprung from the exceptionally “calm” conditions of life in individual small States which have long stood aside and hope thus to stay aside from the bloody world road of war. To be convinced of this it is sufficient, for instance, to ponder over the arguments advanced by the Norwegian advocates of disarmament. “We are a small country,” they say. “We have a small army, we can do nothing against the Great Powers” (and therefore we are also powerless to resist being forcibly drawn into an imperialist alliance with one or the other group of Great Powers…). “We wish to be left in peace in our remote corner and continue to conduct our parochial politics, to demand disarmament, compulsory courts of arbitration, permanent neutrality” (“permanent” after the Belgian fashion, no doubt), etc.

A petty striving of petty States to stand aside, a petty-bourgeois desire to keep as far as possible from the great battles of world history, to take advantage of their relatively monopolistic position in order to remain in fossilized passivity—this is the objective social environment which secures for the disarmament idea a certain degree of success and a certain degree of popularity in some of the small States. It goes without saying that this striving is reactionary and is entirely based on illusions, for imperialism, in one way or another, draws the small States into the vortex of world economy and world politics.

In Switzerland, for example, the imperialist environment objectively gives rise to two lines in the labor movement. The opportunists, in alliance with the bourgeoisie, are trying to convert Switzerland into a Republican-Democratic monopolistic federation for obtaining profits from imperialist bourgeois tourists and to make this “quiet” monopolistic position as profitable and quiet as possible.

The genuine Social-Democrats of Switzerland strive to take advantage of the comparative freedom of Switzerland and its “international” situation (proximity to the most highly cultural countries), the fact that Switzerland, thank God, has not “its own” independent language, but three world languages, to widen, consolidate and strengthen the revolutionary alliance of the revolutionary elements of the proletariat of the whole of Europe. Switzerland, thank God, has not “its own” language, but three world languages precisely those that are spoken by the neighboring belligerent countries.

If the twenty thousand members of the Swiss Party were to pay a weekly levy of two centimes as a sort of “extra war tax”, we would have about twenty thousand francs per annum, a sum more than sufficient to enable us to publish periodically in three languages and to distribute among the workers and soldiers of the belligerent countries—in spite of the ban of general staffs—all the material containing the truth about the incipient revolt of the workers, about their fraternizing in the trenches, about their hopes to use their arms in a revolutionary manner against the imperialist bourgeoisie of “their own” countries, etc.

All this is not new. This is exactly what is being done by the best papers, like La Sentinelle, Volksrecht, the Berner Tagwacht, but unfortunately it is not being done in sufficient volume. Only by such activity can the splendid decision of the Aarau Congress become something more than merely a splendid decision.

The question that interests us at present can be presented in this way: is the demand for disarmament a fitting one for the revolutionary section of the Swiss Social-Democrats? Obviously not. Objectively “disarmament” is an extremely national, a specifically national program of small States; it is certainly not an international program of international revolutionary Social-Democracy.

***

Written in the autumn of 1916. First published in German in Nos. 9 and 10 of the magazine Jugend-Internationale, September and October, 1917, and now included in Lenin’s Collected Works, Definitive Edition (Russian), Vol. XIX, pp. 323-332. Translated from the Russian by Moissaye J. Olgin.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v14n01-jan-1935-communist.pdf