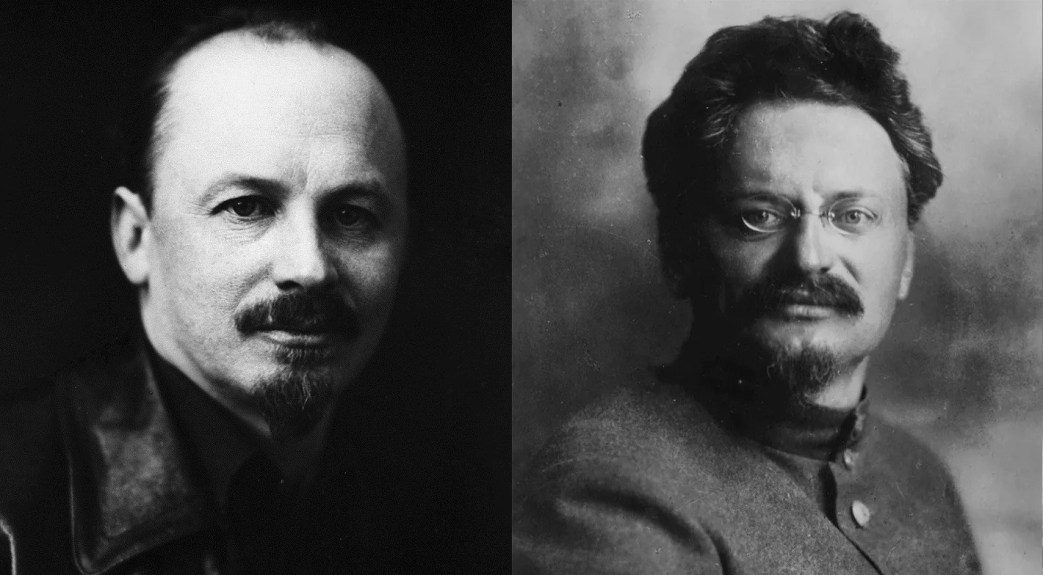

A lengthy, substantial report by Bukharin to his base in the Moscow Committee of the C.P.S.U. on the fierce debates at the Seventh Plenum of the Comintern’s leadership in May, 1927. As part of the factional struggle in the International, Bukharin had taken over from a deposed Zinoviev as the Comintern’s leading figure in the summer of 1926. The main debate at the May, 1927 meeting was over China and the danger of war with the Soviet Union. Zinoviev, Radek, Trotsky, and Vuyovitch were the main figures of the Opposition. The debate was over the most fundamental of questions. What kind of revolution was happening in China, and what kind of revolution was necessary? Are there ‘stages’ in social transformation that must be passed through? What was the ‘stage’ China was passing through? What is a ‘bourgeois-democratic’ colonial revolution in a world economy dominated by imperialism? Is such a revolution necessary before a Socialist revolution can be contemplated? What class leads such a revolution? Is it possible for a combination of classes to lead such a revolution? What is an ‘anti-imperialist’ united front and who can participate when Marxists defined imperialism as ‘capitalism’s highest stage’? Are the peasantry, the overwhelming majority of China, to lead the revolution? Is peasantry a revolutionary class? Can it, or parts of it, become one? And what is the role of the Communist Party and ultimate, and central, aim of a proletarian dictatorship to remake society in their interests? Those debates, because of events on the ground and the Opposition yet to be expelled, peaked in 1927. In April of that year anti-imperialist confrontations in Nanjing and imperialist military intervention signaled both greater strength of the anti-imperialist movement, and imperialist resistance to China’s growing unification movement. Worried over militant and left ascendancy the KMT Right under Chaing-Kai-Shek turned his former allies. In April, 1927 his Nationalist Army approached Shanghai against the militarist clique in control. Communist and Left KMT forces staged an uprising in the city to wrest control before the National Army entered. As it entered, it shot down its former allies by the thousands and the KMT split between Left and Right. The Left KMT regrouped in Wuhan, including members the Communists, and set up a rival Nationalist base. However, on July 15, 1927 the Left KMT Wuhan government, under military pressure from Chang, turned on their Communist allies purging them from the government and outlawing them. The First United Front, a policy central to the Comintern’s larger political perspectives in the mid-1920s was not just over, but a disaster in which thousands of the best Communist fighters in China were killed. As an architect of China policy and an ideological defender of United Front, Bukharin defended that policy at the E.C.C.I. and extrapolates it here–shortly before July’s definitive break with the KMT, and well before the Guangzhou uprising.

‘The Results of the Plenary Session of the E.C.C.I.’ by Nikolai Bukharin from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 7 Nos. 37 & 39. June 30 & July 7, 1927.

Report given at the Plenum of the Moscow Committee of the C.P.S.U. on 4. June 1927.

We append the Stenographic Protocol of Comrade Bucharin’s Speech, with some abbreviations. Ed.

Comrades!

The Plenary Session of the ECCI. just ended, although it has been formally an ordinary regular plenum of the ECCI., is no less important, will prove indeed to be perhaps of even greater importance, than the sessions of the Enlarged Executive. This greater importance arises from the circumstance that the work of the Plenum has been done in the midst of a most extraordinary international situation extraordinary for a number of reasons.

First of all, it was during the session of the Plenum that the rupture of diplomatic relations between the Soviet Union and the British Empire took place. This in itself was an event fully exposing the extreme acuteness of the international situation.

Further, the session has coincided with a new phase in the development of the Chinese revolution, and with this with a new phase in the history of the world. These two events alone suffice to give this Plenary Session, whose main task it has been to deal with these events, a position of unique importance in the history of the development of the Communist movement and in the history of the struggles of the Communist International.

The third factor imparting special importance to this session has been the attitude adopted by the Opposition. It need not be said that I do not think of ranking the attitude of the Opposition in a position of importance to be compared with the great historical events just mentioned. But it is none the less necessary that attention should be drawn to this attitude, the more that the Opposition has never before expressed itself in such a form, in such a tone, or with such purport, Never before has the Opposition taken a stand so brusk, so anti-Party, and at the same time so “decided”, as at the Plenum of the Executive Committee which we have just concluded.

There were three important questions on the agenda. The question of the fight against the danger of war and against war as likely to arise out of the present international situation; the Chinese question; the English question. In the course of the session a fourth question arose: that of the judgment to be formed on the attitude of the Opposition.

On the War against War.

As point of departure we take the incontestable fact that in China a capitalist intervention is going forward against the forces of the Chinese revolution; we base our conclusions for the most part on the assumption which has already almost become an axiom, or will presently become one that the British Government is working systematically, not only to surround the Soviet Union on all sides, but for the preparation of actual war on the Soviet Union. The problems which the Executive Committee of the Comintern set itself the task of solving at this session are the result of the peculiarity of the present international situation, which differs greatly from the situation in 1914, the period which brought us to the threshold of the “great” imperialist war. The tasks confronting us at the present time differ correspondingly from those faced by the organisations of the revolutionary proletariat in 1914. A large number of the problems, slogans, and various tactical tasks, with which we have to occupy ourselves at the present juncture, are bound to differ greatly from the problems, slogans, and tasks falling to the Bolsheviki during the first world war.

The main difference between the events now impending and the events of the year 1914 consists of the fact that this time it is not a question of conflicts among the imperialist powers themselves although such conflicts are in themselves not unlikely but above all of an attack made by the imperialist states against the Soviet Union on the one hand, and against the Chinese revolution on the other. The existence of a Union of proletarian republics, the existence at the same time and under the great influence of this Union of the great Chinese national struggle for emancipation, which has already been able to adopt state forms to a certain extent, and which possesses its organised state centre, the existence of these two mighty historical facts has naturally caused certain questions to be raised by the Comintern, and has influenced its answers.

At the beginning of my report I stated that the existence of the Soviet Republics and of the Chinese revolution changes not only the objective situation, but the whole course of events, and with this the method dealing with the tasks of the proletariat. It need scarcely be said that in the case of a war between imperialist states, it is highly probable that the majority of the working people would take sides with their own government, would once more attempt to solve the question of which side had attacked first, and so forth. But the fact of the Chinese revolution, and of the existence of a Union of Socialist Republics, especially in view of the peace policy which has been pursued, and will continue to be pursued, by this Union of Socialist Republics, are likely to alter the probability of this prognosis a little. For it is easily comprehensible that the greater part of the workers would lend themselves with very heavy hearts to an attack on the Union of Socialist Republics if they can be induced to take part in such an attack at all.

The bourgeois governments will find it increasingly difficult to throw their hirelings and their armed forces against the proletarian republics and their national revolutionary allies in China.

What are the decisions come to by the ECCI. in the question of fighting methods? The ECCI. has decided that the slogan of the general strike, the slogan of insurrection, and the slogan of the transformation of the imperialist war into civil war, are all slogans for the orientation of our Party, and that our main task lies in the preparation for the realisation of these slogans. It is impossible to prophesy when these slogans will emerge from the agitative and propagandist stage into the stage leading immediately to an actual insurrection or strike, when we pass from the propaganda of the general strike or the insurrection to their actualisation. It is perhaps possible to prophesy with a certain amount of certainty that this actualisation will not be possible in the overwhelming majority of states immediately after the beginning of the war. But even today we must face the fact that it may be possible in isolated cases, even if these are exceptional; there can be no doubt that this possibility exists.

The exact moment at which the agitative and propagandist slogans merge into slogans of immediate action will be determined by the situation itself, by the arising of a revolutionary situation, by the strength of the Communist Party, by the degree of fermentation among the masses, by the trends of feeling among the leading strata in a word, by a number of objective and subjective premises. These slogans will merge into slogans of immediate action as soon’ as the proletariat is offered a chance of their realisation.

1. Fighting Methods. General Strike and Insurrection.

I now pass on to the question of fighting methods. When this question is raised, two extremely important documents are generally referred to. Firstly, the resolution passed by the Basle Congress of the II. International, with the well-known amendment to that resolution, proposed by Comrades Lenin and Rosa Luxemburg at Stuttgart and incorporated in the Basle Resolution, and stating that in the case of war it will be necessary: “to make full use of the economic and political crisis caused by the war for the purpose of arousing the people, and accelerating the overthrow of the rule of capital” (Lenin, Complete Works, vol. 13). Secondly, reference is made to one of the last documents dealing precisely with the question of the fight against war–the often quoted instructions issued by Comrade Lenin to our delegation to the congress of trade union, co-operative, pacifist, and other organisations, held at the Hague.

In these instructions Lenin first advances the thesis that we must combat with our utmost energies the foolish and senseless idea that it is possible to “reply” to war with a general strike or a revolution; that in reality the majority of the workers will take sides with their bourgeois government during the first days of a war; that it is of the utmost importance to expose the foolishness of the standpoint of those who imagine themselves in possession of a universal remedy against the “evil” of war; that we must unmask the opportunists, the semi-pacifists, the pacifists, etc., who fancy that they “know” how to fight against war; that we must contend determinedly against the empty phrase of a “reply” to war by means of a general strike or a revolution. These theses are the main import of the instructions drawn up by Comrade Lenin.

Whilst our Commission was working, various interpretations were brought forward with reference to the connection between these instructions of Lenin’s and the Basle Resolution (it must not be forgotten that the formula of the Basle Manifesto was taken from a document which had already been accepted at the Stuttgart Congress. The original wording of the amendment referred directly to revolutionary action, that is to strike and insurrection). The Basle Resolution makes mention of the Paris Commune and of the revolution of 1905, in which the general strike and insurrection formed the “leading forms” of the struggle. The slogan of the general strike and of the armed insurrection was here indirectly presented as a slogan determining our action during preparation for war on the part of the bourgeoisie, and further during the war itself. But on the other hand the Hague instructions state that the phrases on “replying” to a war by revolution are nonsensical; that we have to obey the dictates of common sense, and face the fact that at the beginning of a war the majority of the working people take sides with their bourgeois fatherland.

Various shades of opinion have arisen during the course of our work in the Commission, and we have come to various decisions upon them. One of these may be formulated as follows: The slogans of the general strike and of armed insurrection must stand, without reservation, as rules of action for the Communist Party, both during the period of preparation for war on the part of imperialist states, and during the war itself. Another standpoint: The point of main importance is precisely the exposure of the absurdity of the standpoint that a war can be “replied” to by a general strike, revolution, or insurrection.

What is the right answer to this question? First of all, it is absurd to confront one document with another in this case; it is absurd to confront a document with the demands of the mass struggles of the communards and the revolutionists of 1905, with the “instructions” given by Lenin to the Hague Delegation, dealing with the necessity of forming a careful and attentive judgment of the position, free from all illusions, during the first days or a war.

We must by no means interpret Comrade Lenin’s instructions to the Hague Delegation to be a condemnation of the slogans of the general strike and of insurrection as fighting methods against war danger and war. The sole correct interpretation of Comrade Lenin’s instructions is to realise that they were directed against the mere phrase, the empty phase, of general strike, revolution, and armed insurrection, as “reply” to war. etc. Lenin said no word against these slogans themselves. All that Lenin did was to fight with the utmost political energy against mere phrases, against the empty phrases of reformism.

We know very well that a large number of Social Democratic Congresses, a large number of Trade. Union Congresses, and a large number of the leaders of Social Democratic parties, have repeatedly declared their intention of “replying” to war with a general strike. In the same manner a considerable number of the heroes of the so-called “revolutionary” syndicalism have preached the general strike as the salvation from all evil. But all the same there is no sign to be observed, either in one camp or the other, of systematic preliminary preparation, carried on steadily from day to day, for the actuality of the fight against war.

It need not be emphasised that if anyone were to issue the slogan of revolution and insurrection as “reply” to a war, the single and isolated action of this proclamation would be the vainest of boasts, an utter deception of the masses, unless those issuing the slogan had previously carried through a systematic course of preparation for the organisation of the general strike, the organisation of insurrection, and the organisation of revolution, in accordance with an accurate Marxian analysis of the objective situation.

The point decisive for Lenin–and it must be decisive for the standpoint adopted by the Communist Party–was the orientation of our Party in such manner that our first consideration, our most urgent, important, decisive, and fundamental task, the innermost core of our problem. is to be the proper preparation for the war against war.

This preparation involves the creation of an illegal organisation, it involves work amongst soldiers and sailors, energetic work in the trade unions, the systematic exposure of socialist and opportunist lies, the systematic propaganda of Bolshevist ideas in the struggle against war, and the exertion of every effort for the mobilisation of every possible agitative and propagandist activity, legal and illegal, military and civilian, for the fight against the danger of war. In this manner the question can and must be treated. Those who cry for the general strike as reply to war danger are mere talkers, if not actual betrayers. Those who declare that the working class will “reply” to war by revolution, are mere dealers in words. It is utter nonsense to imagine revolution to be one isolated action, a “reply”. To promise such a “reply”, without a basis of previous work of the intensest nature, is to deceive the workers.

This is the purport of the instructions given by Comrade Lenin to our delegation. The “Hague” instructions do not contain the slightest contradiction of the Basle instructions. These two documents must not be confronted as if one cancelled the other. On the contrary, one gives orientation on certain slogans and fighting methods, whilst the other shows the pivot upon which the whole struggle turns, in order that these slogans may not exist on paper only, but become working slogans leading to corresponding political results.

2. The Central Slogans in the Fight against War Danger and War.

This is the first problem discussed by the Plenum, in its connection with the preparation for war. The second problem is the question of the leading slogan for the Communist Party at the present juncture, under the present given circumstances: An interesting discussion arose sight the question appears perfectly simple, but the course of the discussion showed it to be more complicated, under existing conditions, than in the situation obtaining before the outbreak of the imperialist war. We have to deal with a series of unique situations. First of all, actual war has not yet broken out in Europe, nor has it even actually broken out against the Soviet Union; the main fact is the attack upon the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union represents a factor of extraordinary political importance, and upon its flag the slogan of peace is written.

Let us recall to our memories the manner in which the Bolsheviki dealt with the question of a central slogan at the beginning of the imperialist war, and what differences of opinion existed at that time. The differences of opinion dividing the Bolsheviki from all other ideologies were here very far-reaching indeed. Those of our opponents tending most to the “Left”, including Comrade Trotzky, advanced the slogan of peace as the central unifying slogan, whilst our party and its Central Committee were opposed to the slogan of peace as central slogan, substituting for this the slogan of civil war, the slogan of the metamorphosis of imperialist war into civil war. Here the Party did not advance this slogan as one running parallel to the slogan of peace, not as a slogan compatible with the slogan of peace, but as a slogan excluding the slogan of peace. At that time we contended against all our opponents, including the group “Our Word”, headed by Comrade Trotzky. They advanced the slogan of peace. We advanced the slogan of peace, the slogan of civil war. We regarded this slogan of civil war as the mightiest weapon in the fight against pacifist illusions, including those illusions prevalent in the “left” groups, and claiming to represent a “revolutionary internationalist” standpoint.

Can we, in the present situation, refrain from a recognition of the slogan of peace, at a time when the Soviet Republics, the state organisations of the proletariat, are defending this watchword which their utmost powers, at a time when this watchword actually represents the real and vital interests of this greatest and most important stronghold of the international proletarian movement? And finally, it must not be forgotten that war has not yet broken out in Europe, that an armed attack has not yet been actually made on the Soviet Union, although preparations being made for it with feverish energy. These are some of the considerations which show how complicated the situation has become. On the surface it would appear to be simplest to solve the question as follows: Since there is no war at the present moment, since it is impossible to that the slogans of the proletarian state should contradict the slogans of the Communist Parties, since there is no doubt that enormous masses of the people would support the slogan of peace, and since it is just here that the connection lies between the line of the proletarian republics and the slogan of the broad masses, then the slogan of peace should be made the central slogan for all Communist Parties. It would appear as this method of dealing with the question would be most suitable at the given moment. And yet this is not so. How should we approach the question of the central slogan for all Communist Parties, for the whole Communist International? In order to give an adequate answer to this question, we must find out the hardest knot in the present situation. The knottiest problem of the moment is in the relations between Great Britain and the Soviet Union, and in the attitude taken by the imperialist front towards the Chinese revolution. The driving mechanism actuating all these international entanglements, all the multifarious conflicts, blockades, armed raids, etc., is to be found at the present time in China. The development of the Chinese revolution is the dynamic force throwing out of balance everything upon which our Soviet Union was depending for its pause for breath. The decided advance of constructive socialism in the Soviet Union coincides with a rapid development of the Chinese revolution, a development threatening to overthrow capitalist stabilisation. It is in China and the Soviet Union that the knot of international relations is drawn the tightest.

The Chinese Communist Party is exposed to the direct fire of its antagonists. Can we then put forward the slogan of peace as the leading slogan for the Chines Communist Party? At the present moment the Chinese Communist Party is faced with an emergency demanding a powerful fighting spirit, an offensive spirit, I might almost say, the strongest possible military revolutionary spirit. Should the Chinese Communist Party, the left Kuomintang, the corresponding military organisations, etc., support the slogan of peace, this would be tantamount to a slogan of peace with the traitor Chang Kai-shek, a slogan of peace with the imperialists, etc. And. this at a moment when the military struggle against the feudal regime and the imperialists is a constituent of the revolution still in the initial process of its development.

Should we proclaim the slogan of peace as central slogan, we should thus find ourselves in the position of advancing a slogan supposed to be suitable for all Communist Parties, and especially for the Chinese Communist Party in its present capacity as outpost, and yet having the actual effect of dispersing the forces of one of the most important of the Communist Parties. But the whole political situation demands that precisely this Party should not cry for: “Peace with the feudal lords!”, “Peace with Chang Tso Lin!”, “Peace with Kai-shek”, “Peace with imperialism!”, but rather that it pursues precisely the opposite course, and exerts its utmost efforts to intensify its struggles against these counter-revolutionary forces.

The Chinese Communist Party, at the present political juncture, is not merely one of the Sections of the Comintern, but a Section upon which a political duty of the utmost importance has fallen, a Section which bears upon its shoulders an enormous burden of political responsibility. This Party is under the fire of the enemy, and holds at the moment a place of honour in the field of international revolution.

It goes without saying that a large number of other arguments could be brought forward against the slogan of peace, in so far as it is necessary to contend against pacifism etc. After somewhat comprehensive debates in the commission we held it to be necessary to accept, as central and general slogan, the slogan of the defence of the Russian and Chinese revolution. Everything is included in this slogan: war against war, the transformation of the imperialist war against us into a civil war, the struggle for peace, action taken by the Chinese Communist Party under the slogan of the formation of a front against the imperialists, against Cheng Kai-shek, against the feudal lords, etc. Every action for the pro-motion of the revolutionary struggle can be classified under the heading of this slogan.

These are the most important considerations arising out of the second problem. As you will see, the peculiarity of the decision come to in this question, and the peculiarity of the slogan, which is by no means a simple repetition of the slogans of 1914, arise out of the special peculiarities of the given international situation.

3. Defence and Attack. Defence of Fatherland.

A considerable number of other problems have had to be revised in the same manner. You will all certainly remember that one of the most decisive blows which we dealt against the social patriots was the blow against their “theory” of the defensive and offensive wars of the imperialist states.

At the beginning of a war every single imperialist state involved asserts that it has been “attacked”. The social chauvinists of the different countries have based their policy on the question of this question, the question of who has “attacked” and who “defends”. Our Bolshevik standpoint on the matter has been that this whole definition of the question is nonsense, since in an imperialist war there is neither defence nor attack—every side is attacking. The object of the attack is the colonial countries. Among the imperialist states themselves any attempts to differentiate the “guilty” parties attacking from the innocent who are merely “defending themselves”, is completely absurd.

It is obvious that the existence of the Soviet Union, and of such a factor as that formed by the Chinese revolution, at once set aside any such general definition of the question. For here it is not a question of two imperialist parties, or of state organisations representing different classes.

In our conflict with Great Britain we cannot but maintain the fact that Great Britain has attacked us. We cannot see the situation otherwise, for the truth is that the attack has been made upon us by Great Britain. The policy pursued by the Soviet Union is a true peace policy. Our “attack”, if we may thus express ourselves, has consisted mainly of our economic uplift. But this falls under quite another category.

The standpoint to be adopted in the question of defence of fatherland is even more altered by the latest events. We could not countenance a defence of fatherland among the “great powers” of the first imperialist war, since these powers were imperialist, but in the proletarian republics the situation is entirely reversed, and the defence of the fatherland is the duty of the proletarian parties. Where in the capitalist countries the Communists have been right in adopting the defeatist standpoint, in the Soviet Union our proletarian fatherland must find the fullest support from all sides. There we must reject “defence of fatherland”, here it must be our first thought. This train of thought is rightly applied to the proletarian republics.

But it is equally right when applied to such a government, to such a state organisation, as that represented by the national revolutionary state in China, fighting against imperialism.

Lenin differed from many in dealing with perfect clearness with this question of the defence of fatherland. Whilst conferring with the utmost severity the social patriotic defenders of imperialist fatherlands, Lenin never dealt with the question in such a manner as to assert that if a fatherland is not a proletarian one, there is no reason to defend it. Lenin was very far from such a simplification of the question. He designated the formula of “defence of fatherland” as vulgar and Philistine, as a justification of war, and considered that it had no other meaning whatever.

When we hear of the British defence of the mother country, for instance, this is nothing more than the current expression used to justify a war carried on by the British imperialist government. When we speak of the defence of our fatherland, the question is the justification of a war carried on by us. Lenin did not state that every war is an evil solely because it is a war. War is an evil, and it must be combatted when it is carried on by imperialist states; but we can and must support a war, not when the working class is in power and is defending its state; a war may be supported and justified when it is a national and progressive emancipation war against imperialists, even when the proletariat is not yet its leader. We Communists must therefore stand unconditionally for the support of such a war as that being waged in China for the defence of the Chinese fatherland, for the Chinese revolution.

4. Alliances with Bourgeois States. The Slogan of Fraternisation and of Joining Revolutionary Armies.

The question of the possibility of forming alliances with bourgeois states must be discussed. This question has already been raised at one of the Comintern Congresses, during the debate on the programme. Should such a combination really come to pass that some bourgeois state, under some unlooked for circumstances, and during mighty upheavals, should really take sides with the Soviet Union against the imperialists, then it would be the duty of the Communist Parties to aid the anti-imperialist war being waged by such a state. Should for instance one of the Eastern states, not belonging to the imperialist coalition, be desirous of entering into an alliance with the Soviet Union during a great conflict between Great Britain and the Soviet Union, a conflict into which the whole of Europe would be involved, and the proletarian state had the right, from the Communist standpoint, to enter into this alliance, then the Communists would be bound to aid this alliance.

Here we should not be dealing with an imperialist state, but with a state fighting against the imperialists and on the side of the Soviet Union; this would not simply be a bourgeois state, but a bourgeois state directing its fire against the imperialist regime. Such a state would not be a constituent of the imperialist coalition, but would inevitably, apart from its own volition, as consequence of the objective condition, play the role of a kind of appendage of an anti-imperialist coalition headed by the proletarian republic. One passage from Lenin’s writing contains a direct reference to a revolutionary alliance of India, China, and Persia, without any assumption of the existence of proletarian dictatorship in these countries. You will therefore realise that this question too has its place on our agenda.

I must pass over a number of other questions of lesser significance, and shall turn to a slogan which appears at the first glance to require no alteration conditioned by the development of present events. The elementary and specifically Bolshevik slogan of fraternisation. This slogan was of far-reaching significance for us for our fight against war during the years of the first great international massacre.

Whilst the Executive Committee was working, we asked ourselves whether it would be necessary to undertake any alterations to this slogan as result of the present situation. Can we proclaim this slogan under all and every circumstance, as we could in the years between 1915 and 1918? We came to the conclusion that present situation demands certain corrections in this slogan. We applied the experience gained in our own civil war. The slogan of “fraternisation in the trenches” played a role of enormous importance when the armies of the imperialists, the Tsarist army, or Kerensky’s army, fought against the imperialist coalition headed by Germany. But when the Red Army was fighting against Yudenitsch, against Koltchak etc. did we then proclaim the slogan of fraternisation? No, we did not proclaim it. This is a plain fact which we can all remember.

How did it happen that the slogan of “fraternisation” played so great a part during the imperialist war, but vanished as soon as the Red Army was formed, and this Red Army fought against our antagonists? We came to the conclusion that the slogan of fraternisation is a slogan implying the disorganisation of bath parties thus fraternising, and when two imperialist armies confront one another, the slogan of fraternisation, in so far as it is actually realised, shakes both sides. This being the case, it is clearly comprehensible why we did not proclaim this slogan after we had our own revolutionary army fighting against the enemy. This slogan is a two edged sword, and those fraternising on our side must be really firm in their convictions if the slogan of fraternisation, and the process of fraternisation itself, is not to shake our own revolutionary discipline.

In this question we have adopted the standpoint that in the case of a conflict between two imperialist opponents on the one side, and, let us say, of a proletarian army and a national revolutionary army on the other, our slogan must be a slogan calling upon the soldiers of the hostile forces to come over to us, not a slogan of fraternisation, but a slogan calling upon the others to join us. This does not exclude the process of fraternisation, but it must be very differently organised. We must not induce the whole of our forces to creep into the trenches, but must have our special propagandists, who must be scattered about among the camps of the enemy, and undermine the counter- revolutionary discipline of the enemies of revolution.

Thus the present situation, the existence of the proletarian Soviet state, of the national revolutionary organisation in China, etc., forces us to undertake certain corrections of even such an elementary slogan as that of fraternisation, a slogan apparently perfectly clear and unequivocal.

The Fight against War and the Opposition.

In connection with the war question I must deal with the “platform” of our Opposition with respect to this question. The general estimate of the international situation laid before the Plenum of the E.C.C.I. by the Opposition concludes that at the present time we are weaker than we were before. The comrades of the Opposition have cited a number of defeats: the defeat in Bulgaria, in Esthonia, the defeat in Germany in 1923, the defeat of Chang Kai-shek’s change of front in China, etc. The final result and the final balance is to be summed up in the conclusion that we are weaker than before.

I am of the opinion that in the first place this estimate is entirely wrong. There is of course no thought of denying that there have been defeats, severe defeats. But it is entirely useless to attempt to place these defeats to the account of the so-called “opportunist” majority of the Central Committee, since a large number of these defeats coincided with the culminating point of the leading role played by Comrade Zinoviev in the Com- intern, and of the fairly important part taken in the Political Bureau of the C.C. of the C.P.S.U. by those comrades who are no longer members of this Bureau. I am however not desirous of drawing attention to these matters. I only wish to point out the incorrectness of drawing such wholesale conclusions as the statement that we are weaker at the present time than formerly. There has been a certain regrouping of forces in Europe of late. This phenomenon has received due consideration in the thesis on the “partial stabilisation of capitalism”. The present period is characterised by a temporary firmer footing of European capitalism, especially of central European capitalism.

The utterances denying the partial stabilisation of capitalism are pure nonsense. The economics of European capitalism have become stronger, especially the economics of German capitalism, Enormous amounts of capital have been invested in industry. The fact of an economic uplift is further confirmed by the literary data at our disposal, by the index figures, and by the reports of comrades coming from this country. What will happen later is another question. It is probable that the limited capacity of the home markets will lead to a mighty collapse after the lapse of a certain time, but it is possible that the curve of development may continue to rise for the time being. There is no doubt whatever that German capitalism has a securer footing than before; and there is as little doubt that there is a simultaneous political consolidation of the forces of German capitalism, a co-operation among the agrarian and industrialists belonging to every wing, a firmer establishment of the Fascist organisations, a consolidation of these organisations and their united front, accomplished in the united front in combination with the present German government.

The assertions that Polish capitalism is falling rapidly into decay, are not true by any means. On the contrary, we see that Polish capitalism is passing through a period of incontestable temporary consolidation, both politically and economically. This is based on a number of causes. In the first place, the Polish bourgeoisie was helped by the British strike, and then by a large number of loans and investments, especially from American capitalists.

There is thus no possibility of throwing doubts on the regrouping of forces in the direction of a stabilisation of capitalism, and a consolidation and firmer establishment of its political positions in Central Europe. And there is as little doubt that Zinoviev was in error when he lately stated that the stabilisation had already disappeared.

The greatest peculiarity of the present situation is however the fact that that inequality in the development of capitalism, referred to at the VII. Enlarged Plenum of the Executive Committee, has become more conspicuous than before. The manysidedness, diversity, and inconsistency in the development of the various departments of the world’s economics have found even clearer expression. And though on the one hand we must admit the advancing consolidation of European continental capitalism, on the other hand we observe with equal clearness the rising tempest of the Chinese revolution, which is sweeping through the whole system of international relations in our present state of society, shaking them to their foundations.

When we take into account all these facts of present day against development, and when we duly estimate the immensity of the Chinese revolution and its consequences, and the growing power of the Soviet Union, then we can scarcely arrive at the conclusion “that we have become weaker”. It is true that our antagonist has become stronger (this we admit when we recognise the “partial stabilisation). But a general comparison of forces does not show him to have gained any advantage The formula of our having “become weaker” does not express the actual state of affairs.

The general estimate laid before us by the Opposition is therefore wrong.

Now to the “definite proposals” made us by the Opposition. It must first be observed that all these proposals have been accompanied by unheard of attacks on the C.C. of our Party and on the Comintern. We have never before heard such utterances as these, so rude and insulting, so entirely adventurous, not even during the inner Party and Comintern discussion of the last few years. And yet Comrades Trotzky and Vuyovitch, who have represented the Opposition in the Plenum of the Executive Committee, have literally not brought forward one single definite proposition, not one single word, with respect to the problems which I have touched upon here. And this although I questioned Comrade Trotzky most urgently, in my speech, to deal with the most important questions concerning the preparations being made for war.

During the imperialist war Comrade Trotzky was opposed to the defeat slogan, is he conscious, or is he not conscious, of the error committed by him in the years between 1914 and 1917? Is he conscious of having been in error in rejecting the defeat slogan, and even the slogan of “the conversion of imperialist war into civil war?” Is he conscious of this, or does he acknowledge being in the wrong in advancing the peace slogan as our central slogan?

In asking these questions I am not referring to past times. We are concerned with burning questions of the moment. It is an open secret that we are moving rapidly towards an epoch which will put an end to our “pause for breath”, and are entering on a period involving wars and attacks upon the Soviet Union. We do not know when the storm will break over our heads, but we know that it is approaching, dark and threatening. And now consider carefully! If we take this estimate of our situation seriously, then we must be ideologically prepared for it; fully prepared for it, prepared to hundred per cent. Is it possible to take it less seriously? It is only right to speak of one hundred per cent. We are not dealing with a mere bagatelle; we have to adopt either one definite standpoint, or another; we have to adopt one central slogan, or another. Our decision is of immediate practical importance, and not merely of practical importance for some secondary matter, but for a question of principle, laying down the actual line of orientation for our Communist Parties.

Have such problems as that of “defeatism”, of the peace slogan, of civil war, etc., lost anything of their acuteness? Can we simply pass them by?

Does not the most elementary political conscientiousness demand that Comrade Trotzky either acknowledges that he has been in error in these cardinal questions, or that he is in open opposition to Lenin? Is it so difficult to understand that an attempt to avoid this question at the present time would show utter lack of principle?

And yet, in spite of the open challenge made to Comrade Trotzky, he has uttered no word on all these matters, and we are still in the dark as to what he thinks about “defeatism” and about all his former errors. According to Comrade Trotzky’s conceptions, Bolshevism was “re-equipped” as early, as the spring of 1917, and, having become “Trotzkyfied”, it drew all its weapons from Trotzky’s arsenal. Perhaps Comrade Trotzky advances similar pretensions with regard to the war questions?

Here a definite answer is required. But this definite answer has not been given us.

More than this. We have been given no answer whatever, either definite or indefinite. And this in spite of the unusual energy shown by the comrades of the Opposition, who have let off innumerable quantities of essays, speeches, declarations, explanations, “unheld” speeches, etc. etc. for the benefit of the Plenum. They have placed on this occasion on record documents to the extent of about 500 pages. But in all this voluminous written matter no room has been found for the most important questions of all, no room for a reply to the most fundamental problems, no room for a spark of courage to acknowledge opportunist errors.

In place of this we find Comrade Trotzky touching upon one question only: the question of the Anglo-Russian Committee. To Trotzky this appears to be the sole question worthy of attention, and his reply to it is all he accomplishes in connection with the war preparations! And these are the comrades who pretend to political farsightedness! I too must however devote a few words to this question. Every one of us is able to understand that among the enormous arsenal of defensive weapons at the disposal of the international labour movement, the Anglo-Russian Committee is only one among many. There are other weapons too; there is the Comintern, there is the Red International of Labour Unions, there are about 60 Communist Parties, there is the C.P.S.U., there is the dictatorship of the proletariat, the Soviet Union, there is the Chinese revolution, etc. etc. All these weapons must be mobilised against the danger of war.

But our comrades of the Opposition ignore all these factors with the sole exception of the Anglo-Russian Committee, and have concentrated on this one question the whole of their eloquence, their temperament, their “indignation”, their slanders, and the rest of virtues, with the object of persuading our foreign comrades that the C.P.S.U. has been acting the part of a traitor to the proletariat. It must also be observed that the tone adopted by the Opposition, and by Comrade Trotzky, at this meeting, has been extremely strange. Every word, and every second printed line, contains accusations of “treachery”, of “unfaithfulness”, of “crime”, etc., hurled against the C.C. of our Party and against the Comintern. This has aroused, and is bound to arouse, the greatest indignation among our comrades from abroad. And if a certain amount of sympathy was felt at first, among especially softhearted comrades, for the comrades of the Opposition who have been “pushed aside” and “humiliated”, this sympathy was speedily destroyed, and Trotzky aroused general indignation against himself.

This you may see from the resolutions passed on the attitude taken by the Opposition. The comrades of the Opposition advanced an urgent demand that the Anglo-Russian Committee should be dissolved. We replied that we must not delude ourselves that the British section of the Anglo-Russian Committee would help much during or before a war, but that in the given historical situation, under the given circumstances, it is better to avoid a rupture, since such a rupture would have made an extremely unfavourable impression in view of the various other “ruptures” which we have to record. The Opposition repeated what they said long ago, merely using stronger expressions: You are co-operating with the scoundrels who betrayed the General Strike, etc., and therefore you too are traitors to the working class!

The arguments brought forward here by the Opposition differ solely from their former arguments in being more “de- finite”, more “decided”, and more violent in their attacks on the leaders of our Party and on the Comintern. And yet it is obvious that the problem is not solved by designating both the “Left” and the Right leaders of the General Council as opportunists, reformists, scabs, servants of imperialism, etc. These are sacred and entirely elementary truths. The question is, whether it would have been right to dissolve the Anglo-Russian Committee in the midst of an extremely difficult international situation. We were of the opinion that the situation obliged us to make a number of concessions. This did not by any means signify that our trade unions abandoned their right to criticise. The interview with comrade Tomsky, shortly after the Berlin Conference, showed this plainly enough.

These were the considerations (and not illusory considerations expecting active help) which led to our approval of the tactics pursued by the All-Russian Central Trade Union Council. This does not exclude the possibility that the leaders of the General Council may be induced by our criticism to dissolve the Anglo-Russian Committee themselves. This is not impossible. Our criticism is perfectly necessary. And the English workers will be fully able to realise that our action forces the traitorous leaders to unmask their own treachery, whether they name themselves right or “Left”.

Finally, two further “proposals” were made by the Op- position in connection with the war danger. Both of these proposals are simply ridiculous. One of them was brought forward by Comrade Vuyovitch, with Trotzky’s approval, the other by both Vuyovitch and Trotzky, and is repeated in their speeches, proclamations, etc. The first proposal is that under the given circumstances, and in view of the war danger, our orientation should be in the direction of the anarcho-syndicalist workers. The second proposal is that the group around Maslow, Ruth Fischer, etc., should be readmitted into the Comintern and into the German Party.

A few words must first be devoted to the present “anarcho- syndicalists”. The anarcho-syndicalists count total of 2 1/2. For the most part these are “leaders” without an army. No great anarcho-syndicalist organisation exists anywhere, with the exception of the American “I.W.W.”. It is characteristic that all anarcho-syndicalist organisations still existing in Europe are violently opposed to the Soviet Union, their ideology not differing in the very slightest degree from the Menshevist-social revolutionary ideology. They hold the standpoint that the Bolsheviki have been guilty of threefold treason against international revolution, that our dictatorship is an oligarchy, that our dictatorship is not of the proletariat; they agitate against the Soviet Union with the most despicable methods, etc. And these are the allies to whom Trotzky and Vuyovitch would have us apply, that they may “defend” us! Complete and absolute nonsense!

We have not the slightest leaning towards an “orientation” in the direction of that counter-revolutionary petty bourgeoisie, which is doing its utmost, from day to day, to compete with the leaders of the Social Democrats in the choice of the dirtiest weapons to be used against us. It must be remembered that these elements are not backed up by the masses. This is the rub. In 1914 Trotzky ran accidentally against a anarcho-syndicalists, and stuck there for a time. But now it is no longer 1914. Many regroupings have taken place since then. We have surely no need to light a lantern and go seeking for a handful of anarcho-syndicalists to protect the Soviet Union in an emergency against the imperialists.

Comrades, the idea is perfectly ridiculous, complete nonsense. And it is especially ridiculous at the present moment, when our chief task is to win over the average worker, especially the European average worker, who is, regrettably enough, still in the clutches of the Social Democratic parties and of the Amsterdam International. The problem of winning over the average worker was first raised at the time of the III. Congress of the Comintern, held with the aid of Lenin’s authority, and this problem still confronts as today, more urgently than ever. To create a diversion with respect to this problem would mean substituting Lenin’s slogan, demanding the conquest of the masses, by a slogan calling for the “conquest” of a few counter-revolutionary leaders.

As to Maslow, the proposal with regard to him and his group has aroused extreme indignation among the members of the Executive Committee. You will no doubt recollect that the declaration of repentance made by the Opposition on 6. October, and expressly stated by Comrade Zinoviev to be “meant seriously”, one point was the assurance that the Opposition entirely gives up every connection with the group expelled from the Comintern, the names of Urbahns, Maslow, and others being given. I must here relate a few details on the position of these excluded members. They have their own newspaper, they have already converted this paper into a weekly, and are taking steps towards issuing it daily; they are taking steps towards the formation of a party of their own. There is no doubt whatever that they are in receipt of help from our Opposition, from whom they receive material about our Party life, even to reports on the sessions of the Political Bureau, and information on occurrences in this Bureau.

Steering their course in accordance with the political wind, they direct their attack at times directly against the Soviet Union itself, whilst at other times they adopt a milder tone towards the Union, and direct their efforts to violent attacks on our Party and the Comintern. On one occasion, for instance, they wrote that Stalin does not differ in the least from Noske (Disturbance). I do not understand why you are surprised at that, it is nothing new (A voice: “It is new to us”). Then I am pleased to have been able to inform you of it. (Laughter.) Their newspaper, which has become the organ of our “Opposition” at the present time, dishes up every morsel of gossip or slander in circulation against our Party and the Comintern. These good people will presently arrive at a slogan of “Soviets without Communists”. They have already published an article on war in which they state that, unless the present leaders of the Comintern change their political and organisatory course radically at the last moment, they will play the same role as the leaders of the Second International at the beginning of the great war. (“The Flag of Communism”, No. 12.)

This writes the Maslow pardoned by Hindenburg’s Government, the Maslow who disgraced himself at his trial, about the Parties of the Comintern, and that at time when the Chinese Communists are being strangled, when the French Communists are being thrown into prison, when the Italian comrades are perishing in their dungeons, when the German Communists are organising hundreds of thousands of workers in the struggle against war, when an incredible agitation is being carried on against the Soviet Union, when the whole capitalist world is conspiring together against the Comintern! And these hostile elements (who seek to provoke us further by dubbing themselves “orthodox Marxists”, “Leninists” etc.) are proposed to us as saviours of the German Party.

Our policy in preparing for war, in all that concerns inner Party questions, must consist of ensuring the strength and unity of inner relations in the Party, and of steering a definite course towards winning over the broad masses of the Social Democratic workers.

Our Parties are well aware that they will be plunged into situations in which their lives will be literally at stake if they are to remain true to the Comintern, and to protect with their own bodies the socialist fatherland of the proletariat against the attack of the imperialists. But instead of demanding that our ranks stand closer together than ever, instead of demanding the expulsion of apostates and the winning over of the broad masses, the Opposition proposes that we admit any offal into our Party, the various types of anarcho-syndicalists, the more than suspicious Maslow, the “disciplined” Ruth Fischer, etc., and meanwhile we may forget the Social Democratic workers for the present. We are not in agreement in any single point with this standpoint; not a single comrade has said a word in favour of these “measures”, with the exception of Comrade Vuyovitch, whose fractional interests make him Trotzky’s supporter in all these attacks, sallies, and proposals. Not one single member of the Plenum is agreed with the readmission of Maslow and his group, or with the idea of turning our backs on the broad masses and starting on a search for a few syndicalists to help us to defend the Soviet Union.

The Chinese Revolution.

1. The Regrouping of Class Forces.

It was at the VII. Enlarged Plenum of the E.C.C.I. that a resolution was detailed, and contained an analysis of the econo-International [sic] came into existence, on the Chinese revolution. This resolution was detailed, and contained an analysis of the economics of China and the role played by imperialism, an analysis and estimate of the different class forces in China, an estimate of the relations existing at that time between the various class forces, and a prognosis forecasting the inevitable fresh regroupings arising out of the progress of the Chinese revolution. The VII. Plenum determined the main line of tactics for the Communist Party of China. I begin with the VII. Plenum, in order to emphasise from the beginning that estimate of the Chinese class forces and of the necessary regroupings, which was made by the Communist International long before Chang Kai-shek’s renegacy confirmed this estimate

The VII. Plenum took as point of departure for its resolution the consideration that the growing class antagonism, the development of the agrarian movement and of the labour movement, were inevitably bound to lead the liberal bourgeoisie away from the united national revolutionary front, into the camp of the counter-revolutionists, so that at this point the whole Chinese revolution would enter a new phase of development. During this stage the class forces of the national revolutionary front will have to seek support from the bloc composed of the working class, the peasantry, and the city petty bourgeoisie (artisans, small shopkeepers, small intellectuals, etc.).

Chang Kai-shek’s change of front was nothing more nor less than a crude expression of that transition of the liberal bourgeoisie into the camp of the counter-revolutionists, long prophesied by the VII. Plenum. Chang Kai-shek’s renegacy should not by any means be regarded as the treachery of one isolated general. His traitorous action was merely the military expression of a far-reaching regrouping of the class forces of the country, inevitably resulting from the development of the agrarian movement in the rural districts, and of the labour movement in the towns.

The present Plenum has had to solve the task of observing the lessons to be learnt from the present events, and of deter- mining the tactics to be pursued by the C.P. of China and the Comintern in the new situation. In the first place, Chang Kai-shek’s renegacy has had to be accorded its proper place in the estimate of events. The symbol of the desertion of an extremely large social stratum, a group which played a leading role in that stage of the Chinese revolution from which we are just emerging, and which actually took the part of leader, during the first stage of the development of the Chinese revolution, in the struggle against Imperialism. The liberal bourgeoisie has gone over into the camp of counter-revolution, and the national emancipation movement has consequently been plunged into an inevitable crisis. This crisis has been accompanied by a partial defeat of the Chinese revolution.

At the present time we are up against another combination of social forces, and any line of tactics or strategic measure based on the former distribution of forces would be of necessity counter-revolutionary, and would be condemned to inevitable defeat. Chang Kai-shek’s desertion of the revolution was determined by a number of factors; mainly by the development of the labour movement, the rise of the peasant movement, and the policy of the imperialists. These factors have exercised a mighty pressure on the liberal bourgeois front, and have accelerated the process of desertion of this bourgeoisie from the united national revolutionary front.

2. The Agrarian Revolution and the Peasant Movement.

The E.C.C.I is of the opinion that the central question of the Chinese revolution at the present juncture in so far as its inner driving forces are concerned is the agrarian revolution. It is becoming more and more evident that the peasant movement, the problem of the redistribution of land, of the confiscation of the land in the hands of the small, middle, and large (but few in number) landowners, and all the tasks and problems entailed by these demands, are at the moment the burning questions of the day. It is scarcely necessary to point out here that the peasantry form an exceedingly important section of the Chinese population; nor is it necessary to characterise in detail the social economics of Chinese rural life. I should merely like to emphasise that the course taken by events in China, and the development of the agrarian movement, completely refute the standpoint (as held for instance by Comrade Radek) that there are no remains of feudalism in China, a standpoint which leaves the extraordinary intensity of the peasant agrarian movement in China entirely unexplained.

The agrarian revolution is the pivot upon which events turn. The peasantry of China appear in their overwhelming numbers’ on the stage of history. The peasantry, under the leadership of the working class, will develop into the leading mass force behind the development of the Chinese revolution. The Executive has discussed the solutions to be found for the Chinese agrarian question, and the resolution passed by the Plenum expressly emphasises that, from the standpoint of the development of the Chinese revolution, the most essential step next to be taken is the actual confiscation of the land, the actual overthrow of the old apparatus ruling, the peasantry, the actual redistribution of the land from below, by the peasants themselves, the peasant organisations and peasant committees now springing up in ever increasing numbers.

The importance of these steps cannot be too greatly emphasised, for the illusion still exists, even among the Chinese Communists, and to a much greater degree among the Left Kuomintang, that this agrarian revolution can only be accomplished in the form of an agrarian revolution from above, or must be postponed until China is united. This illusion acts a brake on the development of the Chinese agrarian peasant movement. We only need refer to the last speech made by Comrade Tang Ping Shan, the Minister of Agriculture in the Wuhan Government; this speech did not contain one word on the necessity of the actual confiscation of the lan In the circles around the Wuhan government, and even among certain circles of the Chinese communists themselves, tendencies still exist towards going beyond certain limits of present conditions by means of peaceful enactments, and towards attempting to solve the agrarian problem by means of decrees and similar procedures; and this although civil war has already begun in the country. This is something which has never been accomplished in the history of any revolution, and never will be.

We may further refer to a speech held by another leader of the C.P. of China, Comrade Chen Du Siu, who advanced an even more singular opinion at the Party Conference recently. He stated that we must wait with the agrarian revolution until the Chinese revolutionary troops march into Pekin and drive Chang Tso Lin out of the capital.

And yet it is perfectly obvious that the fundamental premise for the victorious solution of the problems dictated by the Chinese revolution today is the development of the agrarian revolution. From every standpoint the agrarian revolution is the prerequisite from the standpoint of the fight against Imperialism, of the fight against liberal-bourgeois counter-revolution, that is against Chang Kai-shek, from the standpoint of the better self-defence, and further development of the Wuhan Government, from the standpoint of the mobilisation of the most powerful of forces possible in the struggle against counter-revolution.

Not one problem can be solved today unless an agrarian revolution, carried forward by the masses of the peasantry, is an accomplished fact. Even such an elementary problem as the organisation of armed forces leads us inevitably to the necessity of promoting the agrarian revolution, for the simple reason that the Wuhan Government will otherwise not be in a position to win the confidence of the peasants, will not be in a position to gather troops of really reliable soldiers around it, and will not be in a position to give its further successes military security. The central problem, the central task, the central slogan, the slogan of awakening the agrarian revolution. And to accomplish the agrarian revolution the land must be confiscated by the peasants themselves, the ground rents must be abolished, the peasants must rule their own affairs by means of their peasant committees and peasant associations, the masses of the peasantry must be armed, the land taken from the large landowners must be secured by armed defence, etc. etc.

3. The Mass Organisations, the Kuomintang, and the Communist Party.

All this leads us naturally to the problem of organisation. Having seen the necessity of promoting the agrarian revolution to be more important than all else, that is, having recognised the importance of a mass movement, it is obvious that we turn our attention at once to the tempestuously energetic growth of every possible description of mass organisation the peasants unions, the peasants committees, the workers trade unions, the unions of the artisans and small shopkeepers, etc. It need not be said that here the basis must be the mass organisations of the working class and the peasantry.

In connection with this orientation it is natural and com prehensible that the Executive found it necessary to raise the question of the reorganisation of the Kuomintang. The Kuomintang, at the time when it came into being, had an extremely original social and class structure, and at the same time an exceedingly original organisatory structure. It contained not only purely bourgeois elements, forming the social class basis of the so-called right wing, but workers, peasants, petty bourgeois, and intellectuals. The Kuomintang, which was organised in Sun Yat Sen’s time on the basis of the most multifarious military combinations, was an organisation about which almost anything might have been said, except that it was built up on a foundation of inner party democracy. A large number of leaders not only held all power in their hands, but were actually perfectly independent of the local organisations of the Kuomintang. No proper meetings were held nor proper elections organised. This state of affairs will have to be fundamentally changed, the more that the Kuomintang, without a radical alteration in these respect, will never be able to play its part in history, but must inevitably fall into decay.

The split in the national-revolutionary front, the desertion of the bourgeoisie into the camp of counter-revolution, was accompanied by a split in the Kuomintang. This split in the Kuomintang has led to the formation, by Chang Kai-shek, of liberal bourgeois right Kuomintang. The Left Kuomintang now consists of the petty bourgeoisie, the workers, the peasants, and some groups of the bourgeois radical intelligenzia with a few residual elements from the radical strata of the large bourgeoisie; these last play a comparatively secondary role.

What is first to be done, if we are to steer our course towards the agrarian revolution? Our most imperative task is to render proletarian and peasant influence decisive in the Left Kuomintang; not only must this party be a proletarian and peasant party as regards its membership, but this influence must be felt in all its leading organs in town and country.

Yesterday a comrade came to us, a member of the delegation sent to China by the Communist International. He maintained that the relations existing in the leadership of the Kuomintang of the Left Kuomintang do not by any means correspond with the inner structure of the Kuomintang from the standpoint of the real class relations among the masses of its members. He reported that, the Communists exercise a strong influence among the most important mass organisations affiliated to the Kuomintang or formally under its influence.

This means that Communist influence is growing in that mass force which is playing an increasingly important role in the development of the Chinese revolution. And it need not be said that the Chinese Communists are not hundred per cent Bolsheviki; this we must not forget. It would be an illusion to expect even the Communists to be hundred per cent Bolsheviki. Our Party, when it came into being, was a group of intellectuals and workers which had absorbed the whole Marxist experience of the West European Social Democratic movement. The founders of Russian Social Democracy. were thoroughly educated Marxists. In our Party the Marxian principles were ours from the very beginning Our Communist Party in China has been founded on an entirely different foundation. It arose out of Sun Yat Sen’s “Narodnikism” without any knowledge of the principles of Marxism. It is only of late that contact with the Soviet Union and the Communist International has afforded the opportunity for the formation of a Marxist cadres. We must not lose sight of this peculiarity in the history of the C.P. of China.

The necessity of developing the agrarian revolution, the necessity of developing the labour movement and ensuring the growth of the mass organisations, the necessity of utilising the positive traditions of the Kuomintang as an organisation in which the working class comes into immediate contact with the peasantry and the petty bourgeoisie and is able to assume the leadership of these forces, all this has brought the Plenum to the decision that it is most decidedly necessary to reorganise the Kuomintang on the basis of the collective membership of all these forms of mass organisations, that is, the trade unions, the peasants’ union and committees, the soldiers’ organisations, the organisations of the small handicrafts, etc.

In this connection the Executive drew attention to the special tasks falling to the Communist Party, and to the special forms of its relations to the Left Kuomintang. The Executive pointed out that the Communist Party has frequently showed itself afraid of a development of a mass movement, especially of an agrarian movement. This superfluous caution, and the vacillations in the leadership of the Communist Party itself, are closely related to the superfluous “caution” exercised in criticising the vacillations and half-hearted methods of the Left Kuomintang. The resolution of the E.C.C.I. states clearly that the Communist Party, in so far as it forms the vanguard of the proletariat, must assert its claim to independence as the Party of the working class, that it must not hesitate to criticise the vacillations and half-heartedness of the petty bourgeois Kuomintang, that it is indeed its plain duty to criticise the vacillating attitude of the Kuomintang leaders, and that this is the only possible way to push forward the Left radical petty-bourgeois revolutionists in the direction of a consistent mass struggle of the combined peasantry, artisans, and workers.

4. Armed Forces and Revolution.

The problem of the army, and the whole problem of armed forces, is a highly complicated one. It must be admitted that even the Left Kuomintang does not yet represent a bloc of the workers and peasants. It has still a number, of bourgeois radical leaders. The same applies to the Wuhan government. The Wuhan government is still far from being a dictatorship of the workers and peasantry. It can however develop in this direction. It still contains bourgeois radical leaders who may possibly go over to the enemy, and very probably will do so. And if we have to reckon with this possibility in the case of some of the leaders of the Left Kuomintang, and of some of the members of the present Wuhan Government, then we must admit that the possibility is even greater in the case of the army apparatus.

With regard to the Kuomintang, I am not of the opinion that it is liable to any split of appreciable dimensions, likely to cause the falling off of a great many of its members. This is impossible, because the great mass of the Kuomintang (I differentiate between the masses and the heads of Kuomintang) actually represent a bloc of the workers, peasantry, and petty bourgeoisie. But it is characteristic of the present situation that the army, the generals and officers’ staff, do not by any means represent an absolutely reliable force.

The peculiarities of the position must be fully realised. We are of course fully aware that it is possible to make use of the old generals, but only provided certain conditions are fulfilled, that is, provided that the revolutionary power accomplishes a firm establishment of its position, provided that the economic basis of the old regime (feudalism) is undermined, and provided that these generals are deprived of all possibility of an independent political existence.

But all this cannot yet be asserted of the territory under the Wuhan Government. Can it be maintained that the position of even the bourgeois revolution is firmly established here? No, for the landlords and the semi-landlords, with their gendarmerie and police, have not yet been driven away. Generally speaking, even the Wuhan Government is not yet strong enough. And where its military strength is being improved, the footing is by no means secure, since the number of faithful leaders within the army itself is still insufficient. This is very important. In this sense the structure of the Wuhan army has little similarity with the structure of our Red Army. The army in its totality still stands with the Wuhan Government. But no guarantee exists that this will continue to be the case, without more or less considerable conflicts and treachery. Treachery is indeed more than probable, and in a certain sense inevitable.

The Chinese Revolution and the Opposition.

The gist of comrade Trotzky’s utterances is as follows: Chang Kai-shek has caused the Chinese revolution to suffer a defeat, and this has happened because the C.C. of the C.P.S.U. and the leaders of the Comintern have pursued a “criminal”, “treasonable, and “shameful” line of tactics. In Trotzky’s opinion the tactics of the C.C. and of the Comintern deserve these designations, for the C.C. and the leaders of the Comintern have insisted on a Menshevist and not a Bolshevist standpoint with respect to the liberal bourgeoisie. Trotzky reminds us of the attitude taken by Lenin and the Bolsheviki with regard to the liberal bourgeoisie in the bourgeois democratic revolution of 1905, and quotes from Lenin approximately as follows:

The revolution is a bourgeois one, and therefore we must support the bourgeoisie thus speak the Mensheviki; the re- volution is a bourgeois one, and therefore it is necessary to fight against the counter-revolutionary bourgeoisie thus speak the Bolsheviki.

This passage from Lenin is absolutely correct. The differences of opinion between us and the Mensheviki in the revolution of 1905 were along the line of our relations to the peasantry and to the liberal bourgeoisie. We confronted Tsarism and bourgeoisie, including the liberal bourgeoisie then become counter-revolutionary, by a plebian bloc of workers and peasants; the Mensheviki, on the other hand, supported the liberal bourgeoisie, and failed to grasp the importance of the peasantry. This was the main line of schism between us.

If Lenin had written nothing more than this, if China were a part of the Russian Empire of 1905, and if the Chinese bourgeoisie from 1911 to 1926 had been similar to our bourgeoisie, then indeed we would deserve the title of “Mensheviki”. But the truth is that Trotzky and our whole Opposition understand neither Lenin’s standpoint in this question nor the facts, and bring confusion into the whole question.

We must differentiate between a revolution such as the Russian of 1905, and a revolution of an anti-imperialist character Lenin’s in the semi-colonial and “independent” countries. writings point this out with the utmost clearness. Lenin has told us that we may make not only agreements with the bourgeoisie, but may form actual alliances with them (this Lenin wrote and said at the II. World Congress of the Comintern), though of course under the indispensable condition that the independence of our Party, the independence of the workers’ organisations, etc., is secured. Not merely agreements, but even “alliances”. Why? For the simple reason that in such countries the part played by the liberal bourgeoisie is not the same as its re in Russia in 1905. In 1904 the bourgeoisie still opposed Tsarism, but after the October Strike of 1905 the liberal bourgeoisie had become already an openly counter-revolutionary force. The fact that the liberal bourgeoisie had never once lifted a finger against Tsarism, that it was entirely unable to do so, and that it was bound to go over into the counter-revolutionary camp with the utmost rapidity, was the basis upon which we laid down our line of tactics towards the liberal bourgeoisie.

And now, since Chang Kai-shek has betrayed the revolution, has the Chinese bourgeoisie become counter-revolutionary? Yes, it has become counter-revolutionary. But did it play a counter-revolutionary role between 1911 and 1926? Who is in a position to assert this? Now, indeed, it has gone over to the counter-revolutionary camp, but for many years the part it played made it our duty to support it. We were obliged to utilise it, we were obliged to form a bloc with it. The Communist Party had just been born, the labour movement was making its first steps forward, and the liberal bourgeoisie was fighting against the feudal lords and the imperialists, fighting even with arms. A comparatively short time before Chang Kai-shek’s desertion, his troops undertook the “Northern campaign”. The question is: Was it our duty to support the Northern campaign or was it not? Was it our duty to support the Northern campaign, that Northern campaign which Radek has described as a brilliant revolutionary action?

In China the liberal bourgeoisie has played an objectively revolutionary role for many years, and has exhausted itself. It has however been by no means a political mayfly, living one day only, of the type of the Russian liberal bourgeoisie in the revolution of 1905. The fact that the bourgeoisie has played this particular role is due to the special combinations of social forces ruling in China, to the anti-imperialist national emancipation character of the Chinese revolution; it has been due to a number of causes which had no parallel in the Russian revolution of 1905. It is true that Lenin stated the difference between us and the Mensheviki to consist of the fact that the Mensheviki supported the liberal bourgeoisie, whilst we were opposed to any sort of an agreement with them. But when Lenin said this, he was speaking of the Russian revolution of 1905. He spoke very differently of the revolutions in the East.

The Opposition, in advancing the thesis of the unallowability of an agreement with the liberal bourgeoisie in China, is’ therefore guilty of a distortion of Lenin’s teachings. A method is fundamentally wrong which makes no difference between Russia and China, between 1905 and 1927, between the Russian liberals and the Chinese national revolutionary bourgeoisie, etc., and which states categorically that all cats are grey. Here we find no analysis, no comprehension for the peculiarities of Chinese development.