Two years later saw still the ‘wave of indignation growing in volume and power’ as Boston, Philadelphia, New York, and Chicago observe the second anniversary of the Haymarket executions on November 11, 1889. Some remarkable primary-source radical history here.

‘November Eleventh’ from Workmen’s Advocate (New Haven). Vol. 5 No. 46. November 16, 1889.

THE WAVE OF INDIGNATION GROWING IN VOLUME AND POWER.

Ten Thousand People at the Doors of Cooper Union–A Great Celebration at Waldheim Cemetery–The Day in Boston and Philadelphia.

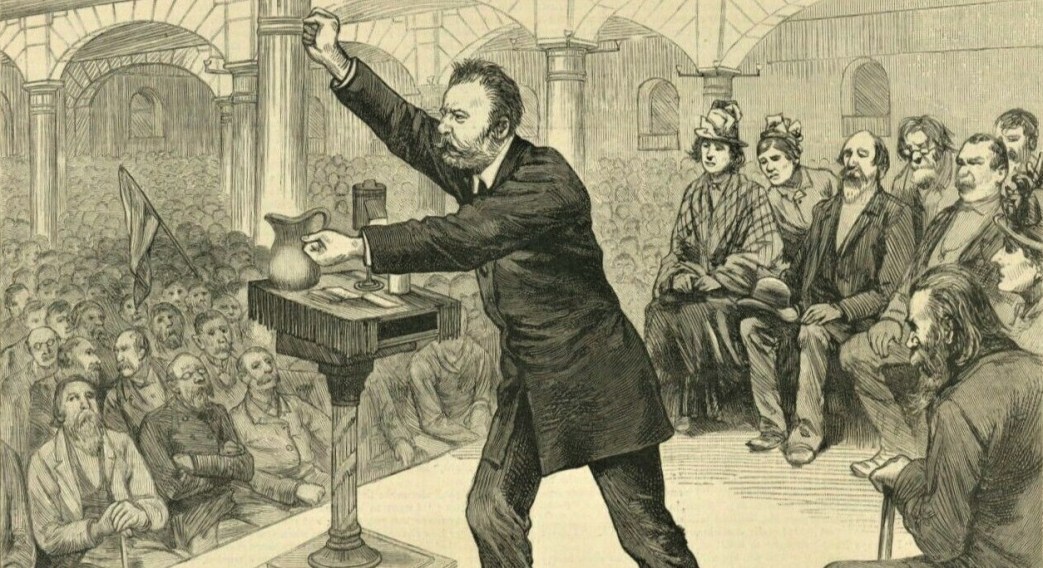

Contrary to its well-known habit of minimizing every demonstration of workingmen, the press of New York did not attempt this time to make it ap- pear that the memorial meeting in honor of the Chicago martyrs at Cooper Union last Monday was an insignificant affair.

We quote from the Herald:

“The big hall was filled to overflowing, and standing room, even in the corridors, was impossible to obtain. It was estimated by the police, of whom very few uniformed members were in sight, that over two thousand people were turned away from the doors.”

The Sun says:

“The law that forbids the crowding of aisles and exits in places of amusement or public gathering, was suspended for the occasion by the police. Not a policemen in uniform was inside the big hall, where thousands were treading on each other’s toes. It was impossible for a strong man to force his way in after 8 o’clock, and it was impossible for the weaker to get out…Five policemen, under the command of a sergeant, were outside the hall. One of them admitted that it was a violation of the law to allow the aisles and exits to be crowded, but said that an order had been issued forbidding them to go inside or to interfere with the meeting in any way unless actual violence occurred.”

The Morning Journal’s estimate of the number of people who surged about the doors of Cooper Institute is “over ten thousand.” We quote:

“The streets for blocks around the entrance were black with men and women, struggling to attend the great demonstration in memorial of the martyrs of the working people, murdered at Chicago.”

At 8.30 a reporter of the Times, a square-shouldered, powerfully built man, was seen elbowing his way through the crowd in the hall. It had taken him twenty minutes to come down from the street, and it took him twenty minutes more to reach the reporters’ enclosure. After all these efforts he had the mortification of seeing is elaborate report thrown by his chief into the waste basket. The editor of the Times, struck dumb with astonishment or fear at the magnitude of the demonstration, concluded to say nothing whatever about it. The World, who of all the New York papers was the most bloodthirsty advocate of the Chicago murder, appears to have been as badly thunderstruck as the Times.

It concedes that 5,000 people at least were in the hall and the corridors, but its report of the proceedings fills only thirty lines of type, under the deceitful title, “Insulted the Stars and Stripes.”

The stage was draped in mourning and between red flags covered with black crape hung the pictures of Spies, Lingg, Parsons, Engel and Fisher. The mottos on the walls were terse quotations from the utterances of the victims during their trial and shortly before their execution. The platform was crowded by musicians and singers respectively furnished by Progressive Musical Union No. 1 and the Socialistic Sængerbund. Comrade Henry, of Cigarmakers’ Union No. 90, presided, After the Dead March had been played by the band, S.E. Shevitch took the floor. He said in part:

“Fellow Murderers: The press of this so-called free country says that all of us here and about here, ten thousand in number, and all who to-night in every great city throughout the civilized world have assembled for the same purpose, are murderers, because we sympathize with murderers. Therefore I address you, workingmen of New York, with this title, Fellow Murderers. [Great laughter and loud cheers.] One of the papers of this city, edited by the Rev. Colonel Shepard, says I must remember that to incite to arson and murder is a crime [Laughter). I will certainly not incite to arson, because I am not a member of the Standard Oil Trust. I will not incite to murder, because I am not a Kentucky politician or a Pinkerton detective. We have not come here to murder, or to incite to murder, or to honor murderers, but to brand murder as it deserves.” [Great cheers.]

Amid the most impressive silence, interrupted from time to time by ominous exclamations of disgust when the names of Grinnell, Garry and Bonfield were spoken, Shevitch reviewed the events preceding and following the arrest of the five Chicago Anarchists. He showed how prejudiced the jury was, how the prosecution had forged evidence, how witnesses had perjured themselves, how, in spite of all this, it was impossible to trace the bomb, or the knowledge of it, to any of the accused men, and how they had been sent to the scaffold as a bloody offering to the frightened divinity of capital by its cowardly ministers.

“These,” said be, “either must have known that they were using the forms. of law to commit a crime, or they were unutterable fools and idiots. Great cheering. But if it was their purpose to strike terror unto the hearts of the working class, what a mistake they made, as we see here to-night! Can such movements, can any movement of ideas be stopped by hanging a few men? Was the movement for the abolition of chattel slavery stopped by the hanging of John Brown? No; such movements cannot be stopped by a million of bayonets. [Prolonged applause.].

“Again,” continued the speaker, “it is customary for those who would arrest progress in this country by persecution, to arouse, or attempt to arouse a false feeling of patriotism by representing that the advocates of modern ideas here are ignorant foreigners, who contemplate the overthrow of the American Republic. In the first place, they should answer this question: Is this country a republic? Can a country claim to be a republic, where the office of President is bought and sold by a plutocracy; where money is the standard of respectability; where the masses of the people, dependent for the means of life upon gigantic monopolies, must vote according to the dictates of their employers, and where the women of the highest classes prostitute themselves for the lowest coronets of Europe? [Hisses.] Are not such women as bad as the unfortunate, on the Bowery who sells herself for fifty cents? Worse, much worse; for the low prostitute is driven by starvation to make an infamous trade of her body, whereas the wealthy daughters of our monopolists, enriched by the labor of American workingmen, is driven to the same shameful deed by a vile anti-republican ambition.”

The speaker here showed what a progress the modern ideas had made of late years among the native born citizens. They have taken deep roots in the American mind and the cry of “Foreigner” has lost its power. Here is,” said he, “Mr. Hugh O. Pentecost. [Cheers.] As long as he was a minister and drew a salary of $5,000 a year he was respectable, but now he is looked down upon. Yet he is not a foreigner, nor is he found discussing anarchistic principles in saloons with a glass of beer in his hand.

“As to the charge that we want a bloody revolution, the answer is, that, taught by history, we merely predict it. Social revolutions are never peaceful. Was the first shot of the American Revolution from the ballot box? No, a gun. Did Washington free this country with a ballot-box? No, with a sword. Were the slaves liberated by ballots? No, by bullets. Organize unions, political parties, anything to promote the movement, and the end–well, the ruling class will be the first to shed blood.

“Two years ago the police of New York dispersed by force in the most unexpected and brutal manner, a peaceful and lawful meeting of the Progressive Labor Party in Union Square. It was all a mistake, they said. We determined to vindicate the right of free speech by holding another meeting at the same place a few days later. Fearing another Mistake, two thousand at least of the fifteen thousand workingmen present at this great demonstration came armed with pistols. I knew it, and had there been a row, I suppose I would have been hanged. Evidence would have been manufactured to show that not the police, but the committee of arrangements had caused the riot.

“Curse on every prosecutor,” concluded the speaker. “Curse on every so-called labor leader who withdrew like a coward two years ago. Curse on the man who, the year before, had pretended to represent the workingmen and then endorsed the Chicago murders. Curses on the hypocrites and sycophants, and curses on the whole social system that produces such things!” [Prolonged applause.]

John Most followed with a speech in German, dealing chiefly with the history of the Chicago tragedy and predicting the triumph of the working class and the abolition of capitalism.

Between the speeches the Socialistic Sængerbund and the band delighted the vast audience with magnificent music, and, at 11 o’clock the crowd slowly wended its way to the street singing the Marseillaise.

THE MEMORIAL CELEBRATION IN CHICAGO.

Although the sky was very cloudy and rain was threatening all day, the two long trains chartered for Waldheim were full of passengers and at half past two o’clock about four thousand persons were assembled in the cemetery to honor the five men who, two years ago, died for the emancipation of mankind. The administration of the cemetery, although they had threatened to have the demonstration prevented, had not dared to do anything in this direction. Neither had the talk of the police that they were going to break up the gathering, nor the shameful articles of the capitalistic press deterred the people from coming. The demonstration was equal in numbers to that held on the same spot last year. The celebration began at half past two with a “Trauermarch” by the Central Music band; this was followed by the United singers, who, two hundred strong, sang “Ueber allen Wipfeln ist Ruh.” Then C.G. Clemens, a lawyer of Topeka, Kansas, was introduced as the English speaker of the day. He said that he took the same view of present social conditions as Bellamy did in “Looking Backward.” He was not here, however, as a Nationalist, a Socialist, or an Anarchist, but as a citizen of the United States. He was not advocating force or dynamite, but freedom of thought and freedom of speech. Spies and his friends had been hanged, not because they were Anarchists, but because they advocated freedom. Mr. Clemens then drew a very able parallel between the present times and the times immediately preceding the abolition of chattel slavery, and he showed, by reading some sections of old Southern statutes, that the same laws had been enacted against the Abolitionists and their so-called conspiracies as are now in force against the working class and its defenders. He reviewed the Anarchist trial from a legal point of view and concluded with a warm appeal to the people, entreating them to educate themselves by reading “Looking Backward.”

As Mr. Clemens spoke for nearly an hour and only those could hear him, who stood very near the speaker, the audience grew somewhat restless during the later part of this oration. At its close a song was rendered. Then Paul Grottkau came forward and delivered in German the most eloquent speech that he ever made. In his opening remarks he commented severely upon the administration of the cemetery, who had done everything they could to prevent his great memorial demonstration. “Nevertheless we had all come, and we would. continue to come and our children after us, and the workingmen of Chicago would celebrate the Eleventh of November long after the names of the present administrators of the Waldheim cemetery were forgotten.” He then asked the question, “What had those five men done? By what means had they become immortal and dear to the hearts of all the oppressed?”

“Many people, to be sure, have done and are still doing as much as they ever did for the cause of mankind, yet were and would remain unknown. These five men were dear to every heart, they were immortal because they were the first victims in the war for the emancipation of the white slaves, and because the day of their murdering marked the beginning of a new epoch in the world’s struggle for freedom. And although they had committed no crime they did not regret life, they did not give way to a feeling of awe in the presence of death, but they met their doom without a tremor. They showed by their behavior that our cause was so noble, so grand, that it could fill its apostles with the greatest courage and sustain them, unflinching, upon the gallows. And for this, said Grottkau, we must be grateful to them.” Grottkau then made a striking comparison between the murderers of Cronin and the murderers of our brethren. He said, “There is an organization in this country consisting mostly of Irish workingmen. These poor fellows and their poor Irish sisters in domestic service save up their nickels, their dimes, and their quarters and contribute them to a fund for the emancipation of old Ireland. But this money, so hard to get yet so freely given, was stolen by a gang of thieves known as the “Old Triangle.” Then there came a man, and his name was Cronin, and showed to the poor Irish workingmen and servant girls now they were robbed. And the robbers said: “Why, this fellow is going to spoil the whole business; he must be done away with.” And he was murdered. The Anarchists did exactly what Cronin did. They showed the people how they were robbed, and the Capitalists said: “Why, those fellows are going to spoil the whole business, we must hang them.” And they were hanged. There is, however, a characteristic difference between the Garys and the Grinnells on one side, and the murderers of Cronin on the other side. The latter are at least ashamed of their foul deed, but the murderers of the Anarchists boast of theirs and erect a monument to celebrate it.”

An immense burst of applause greeted this conclusion of Grottkau’s speech, after which a song, entitled “Am Orabe unserer Freunde,” was rendered by a chorus of two hundred singers. The last speaker was Jacob Mikolanda who addressed the audience in Bohemian.

THE DAY IN BOSTON.

Paine Hall was filled with an enthusiastic audience, composed of all nationalities. On the walls, which were draped with red flags and streamers, were large pictures of the eight victims, framed in evergreen. At the left of the platform was the picture of a gibbet, from which a body dangled, and around this was the inscription: “The cross of the new crusade. In hoc signo vinces.” Above was the American flag, union down.

Other cards in different parts of the hall bore the following words: “To kill is not to reply”; “The United States Government monopoly’s efficient weapon”; “The holy trinity of monopoly–pulpit, press and forum”; “What evil hath he done? Why crucify him?”

“We mourn labor’s martyrs, and pledge ourselves to their principles”; “The John Browns of the industrial war”; “To proclaim the truth, now as ever, is punishable by death.”

The proceedings were opened at 7.30 P.M. by the Arbeiter-Liedertafel, who sang the Marseillaise in German. J.W. Badger, who presided, then read letters from S.E. Shewitch, Hugh O. Pentecost, Rev. John C. Kimball and others, who had been invited as speakers, but were unable to attend. He said this gathering to honor the martyrs who died in Chicago was a more eloquent answer than words to the flimsy commentaries of the press. The workingmen are awakening to the fact that the Chicago martyrs died for the freedom of labor, and, as a result, more than twice as many were present to-day as there were at the memorial meeting a year ago.

Mr. C.S. Griffin made an eloquent speech, frequently interrupted by applause, in which lie described the men who had been executed, their trial, their fortitude, and their hope in the near triumph of the cause for which they died.

After he had resumed his seat the Arbeiter-Liedertafel sung the “Freiheit” chorus, and resolutions were adopted demanding the release of Neebe, Schwab and Fielden from imprisonment, and Mrs. Merrifield read a poem written by her for the occasion. Then Victor Yarro–a Russian journalist of ability, urged the audience to continue the work of social education, which the Chicago agents of capitalism hail vainly tried to stop by murder. He was followed by A.H. Simpson, who in the course of his address observed that Paine Hall was the only hall that could be obtained for the meeting; but it was very appropriate that it should be held there, since we are trying to carry out the principles set forth in Paine’s ” Rights of Man.” Mrs. M. Merrifield made the last speech, vigorously exhorting her hearers to be true to the principles of Socialism.

THE DAY IN PHILADELPHIA.

We have no direct report of the memorial celebration in the Quaker city, but from the special despatch published by a New York contemporary of the blackest capitalistic hue it appears that there as here the public sentiment against the murderous methods of Capitalism has grown to tremendous proportion. We quote from the Herald:

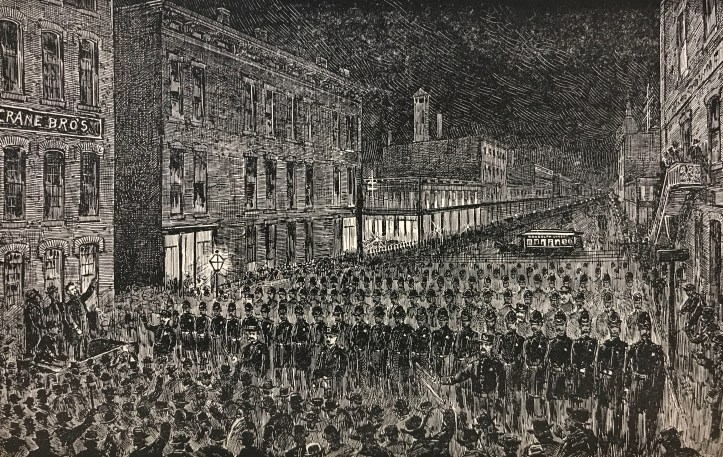

“Philadelphia, Nov. 11, 1889. The anarchists outwitted the police to night and their celebration of the anniversary of the Chicago Haymarket tragedy came off with great eclat in the obscure hall at No. 808 Marshall street The police were in total ignorance of the place of meeting, and therefore the shouters and their audience were not molested. Not since the memorable riots of 1877 had the police made such extensive preparations to preserve the peace. Early in the day Director Stokley was in consultation with Superintendent Lamon. “The anarchists must not meet.” Said the director. “The trustees of Odd Fellows’ Hall, Third and Brown streets have agreed to our request not to open the hall.”

It was decided to place six hundred policemen at the disposal of the superintendent. Of this number live hundred were to be held in readiness to be called at two minutes’ notice. The rest were assigned to preserve order. The greatest precaution was taken to prevent any attempt to force an entrance into Odd Fellows’ Hall. Lieutenant Albright was assigned with several policemen to stay on the outside while in the hall a squad of policemen were to be kept in readiness to repulse the anarchists should they happen to secure an entrance. Lieutenant Albright and his squad took their position at half-past one o’clock this afternoon with instructions to remain until midnight.

The news that the police were to prevent the meeting had spread, and at eight o’clock fully five thousand people had gathered about Odd Fellows’ Hall. A great procession arrived a little before eight o’clock, and being informed by the justice that the meeting was prohibited they quietly dispersed, but only to gather quickly at No. 868 Marshall street, where a crowded meeting was harangued by Julius Mitkiewiez and Martin Kleimer in glorification of the Chicago “martyrs”.

The Workmen’s Advocate (not to be confused with Chicago’s Workingman’s Advocate) began in 1883 as the irregular voice of workers then on strike at the New Haven Daily Palladium in Connecticut. In October, 1885 the Workmen’s Advocate transformed into as a regular weekly paper covering the local labor movement, including the Knights of Labor and the Greenback Labor Party and was affiliated with the Workingmen’s Party. In 1886, as the Workingmen’s Party changed their name to the Socialistic Labor Party, as a consciously Marxist party making this paper among the first English-language papers of an avowedly Marxist group in the US. The paper covered European socialism and the tours of Wilhlelm Liebknecht, Edward Aveling, and Eleanor Marx. In 1889 the DeLeonist’s took control of the SLP and Lucien Sanial became editor. In March 1891, the SLP replaced the Workmen’s Advocate with The People based in New York.

Access to PDF of full issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90065027/