Freeman remembers first meetings with leading Communist figures Bill Dunne, J. Louis Engdahl, William Z. Foster and Charles E. Ruthenberg in some essential U.S. left history.

‘Some American Communists’ by Joseph Freeman from Partisan Review. Vol. 3 No. 1. February, 1936.

[This is an excerpt from the author’s forthcoming book. An American Testament, which will appear in the spring. This section refers to the narrator’s contacts with the American Communist Party in 1922, when the Liberator was the organ of the revolutionary writers and artists of this country.]

ALTHOUGH The Liberator was in no way officially connected with the organized communist movement, I frequently went to Party headquarters to get material for editorials, or to obtain an article from some member of the Central Committee. In this way I became acquainted with several leading communists, whom I had known only by reputation.

Of Bill Dunne, we had heard a great deal as the hero of Bloody Butte. He was a worker who had come into the communist movement through direct struggle with the exploiting class. For years he had been active in the copper-miners’ union and the Democratic Party of Montana. He played poker with Burt Wheeler and had been elected to the state legislature on the Democratic ticket. For a long time Bill had not seen the disparity between his politics and his trade unionism. The open-shop drive which swept America after the war disillusioned him. He published a paper for the union; when the employers attempted to suppress it, he took the printing press to an abandoned church. The mine-owners sent armed thugs to seize the press by force. But Dunne and his wife Marguerite had taken rifles with them. They kept up a running fire until they drove off their attackers. By the time they left Montana and came east, they were convinced communists. Their experiences, combined with their reading of revolutionary literature, had led them to believe that communism alone offered a solution for the American workers, as for workers in all countries.

This was the story I had heard about Dunne when I began to meet him frequently, in the fall of 1922 and in the following spring, at Party headquarters, at John’s restaurant on East Twelfth Street, at the Liberator office He was short and stocky, with a tremendous barrel-chest, solid as a rock, and a dark, heavy, Irish face. His close-cropped bullet head and thick neck gave him the appearance of great physical power; and his deep, husky voice, pouring out a flood of rhetoric, witty and incisive, revealed a mind that was at once brilliant and too fanciful for a practical politician. His whole body, built like a retired prizefighter’s, shook with repressed laughter when he told an anecdote. Dunne’s reading was wide, ranging from Lenin to Joyce. On the platform he thundered in the style of the nineteenth-century orators, and his articles in the Party press were florid, colorful and full of acid.

Dunne’s chief interest was the trade union movement. The Party was then setting its face against dual unionism and had raised the slogan of “boring from within” the conservative unions. Dunne was carrying out that policy in the American Federation of Labor, of which he was still member.

Occasionally he dined in the Village with the Liberator crowd, with whom he felt a certain affinity as a frustrated man of letters. He had the traditional Irish poetry in him, and wanted to write some day, if only an autobiography. Until then he would content himself with the next best thing—talking about literature. Yet his contempt for the literary trifles of bohemia was boundless. Himself strongly sensuous and full of the love of life, he derided intellects dribbling their power away on the abstractly erotic. Good literature in our day, he said, could arise only out of the class war. He often used the word “intellectual” as a term of contempt, as I had heard Louis Smith use it in the slums a decade earlier. This time, however, I understood that what the communist organizer scorned was not intellect—which Lenin, for example, had to the degree of genius—but the phony arrogance of the bohemian literati who fancied they had a monopoly on brains and knowledge, whereas they actually understood nothing of the essential struggles of our epoch. There was this paradox, too: the intellectuals in the Party pretended to be interested only in the working class; Dunne, himself a worker, was also interested in the intellectual.

I first met William Z. Foster through Louis Smith, and was pleased that he who had first introduced me to communism in boyhood should now introduce me to the chieftain of the great steel strike and an outstanding Party leader. A worker by origin, the product of stockyard, street-car, factory and ship, Foster looked more like an intellectual! than most professors I had met. His thin, wiry body was surmounted by a large head which rose from a round, strong chin to a broad forehead and temples enlarged by baldness. His clear blue eyes were by turns austere and mild, his voice soft. Foster talked only about the class war. His questions about my European life ignored art and literature, Dada, the Rotonde, la vie de bohéme. These did not exist for him. He wanted to know about the trade unions, the growth of the communist movement, international politics. Anything he said about himself was a parenthetical illustration of general law of revolutionary strategy or a trade union principle.

“That’s no good,” he would say about some suggestion. “I tried that in the Chicago stockyards, and it doesn’t work.”

Then, merely to clarify his point, he would tell his experiences in organizing the stockyard workers. More personal characteristics emerged by accident. When we had dinner in a Third Avenue cafeteria, I discovered that Foster neither smoked nor drank, and that he was a vegetarian. But he had no puritanical precepts on these matters. The problems of personal conduct which agitated us in the Village did not interest him. He was ascetic by a standard which determined all his actions. The class-struggle was the most important thing in the world, and for that struggle he wanted to keep physically, mentally and morally fit. A touch of tuberculosis which he had cured by shipping as a sailor for several years, a bad heart which was eventually to incapacitate him, obliged him to be especially careful.

Within the Party, Foster had an engaging modesty; in contact with the enemy-class there emerged a powerful pride in which his person and his class were identical. Once the Newark police broke up a street meeting at which he spoke. The Civil Liberties Union—of which Foster was then a leading member—protested and was told that if Foster would appear in person before the city commission and ask for a permit he would be allowed to speak. Foster took me with him to Newark. We were ushered into a large, smoke-filled room in the city hall, with a heavy oak table in the enter, wooden arm-chairs, and a red plush carpet studded with spittoons. The five commissioners sat around the table sullenly. They were either too fat or too thin; their faces were sallow and smirking, the typical faces of petty machine politicians. One of the commissioners, a tall, gray-haired man with tortoise-shell glasses, politely asked us to sit down. Then, very politely, he asked Foster when he wanted to speak, under whose auspices, on what street-corner, on what subject, what literature was going to be distributed. Foster answered gravely, quietly, respectfully. His views were well-known, he would say what he had said at hundreds of meetings throughout the country, he would distribute the literature which the Newark police had illegally confiscated at his last meeting. Would Foster guarantee there would be no disturbances?

“Any disturbance I’ve ever seen at a workers’ meeting,” Foster said, “was created by the police or the American Legion.” This polite conversation went on for over an hour. Suddenly one of the silent commissioners, a fat, pudgy little object, yelled: “We’re wasting time! We know what you’re here for, Mr. Foster. You’re here to make revolutions! We won’t let you do it, understand? You can’t speak in Newark.”

“I am here,” Foster said, “to exercise my right as an American citizen to discuss publicly economic and political questions. You said if I applied in person for a permit you would grant it. I am applying for it now.”

The commissioners laughed. “You can’t talk in Newark,” the grey-haired man with the glasses said. “Not while we run this town. This conference is over.” The commissioners stood up.

Foster’s face turned white, then very red. He turned to me and said in a strained voice: “Let’s go.”

“No hard feelings, Mr. Foster,” one of the commissioners said.

Foster did not answer. We walked out of city hall and for several blocks neither of us spoke. Then Foster broke out: “Goddam their dirty hides! They can’t even keep a promise. I am the physical, mental and moral superior of any man in that room; I could wipe Newark with all five of them at once; and I’ve got to crawl on my hands and knees before them to beg for permission to speak. A permit to which I’m entitled—which they promised!” Then he quieted down and said gravely: “It wasn’t meant for me. The working class has no rights under capitalism.”

Later, when the Party took over the Liberator, I shared a back room at headquarters with Louis Engdahl, one of the five socialists indicted in Chicago during the war, now editor of the Weekly Worker, official communist organ. Engdahl was a tall, redfaced middle-westerner with greying hair carefully brushed back and heavy glasses. He spoke in a flat monotone and seldom laughed. In conversation, oratory and articles he was a master of cliché; but he worked with the energy and endurance of ten men. No matter how early in the morning you came, or how late at night you left, Engdahl was busy at his desk. He did not leave it even for lunch, but nibbled at a dry sandwich or a piece of chocolate while typing or editing copy. He made up for lack of originality by a boundless loyalty to the cause in which his whole being was wrapped up. I worked by his side day after day for six months, and saw him frequently in subsequent years until his untimely death, and we were friends; yet it was a rare occasion when he referred to the little he had of private life. Everything revolved for him around the movement. If we went for a soda, he would ask the clerk about conditions in the drug-stores; after a movie, he would lecture you about the importance of the film, how it concealed real conditions and bamboozled the masses. His greatest passion, however, was the revolutionary press; to this he gave the best of his enormous energy and loyalty; and as time went on I could not help comparing the permanent results of his devoted plodding with the ephemeral flashes of more brilliant but less disciplined journalists on the fringes of the movement.

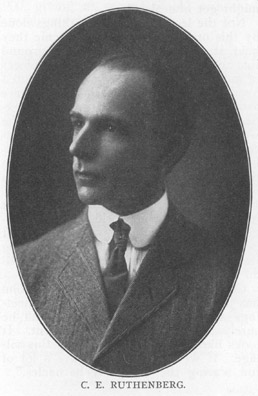

Now and then I had conferences with the Party secretary, C.E. Ruthenberg, a blond, blue-eyed Nordic of German stock, native of Cleveland, son of a longshoreman, accountant by profession. He had given up that profession long ago when he became an organizer for the Socialist Party in his twenty-sixth year. We had heard of him for years as a leader of the revolutionary wing of the socialist movement. When the United States entered the War in 1917, he was among the most vigorous champions of the St. Louis resolution. His active propaganda against the war resulted in arrest; he was sentenced to a year in prison. Released on bail while his appeal was pending, he ran on the Socialist ticket for mayor of Cleveland, basing his campaign on uncompromising opposition to the war. Despite military mobilization, war hysteria, official terror and White House demagogy, Ruthenberg received more than one-fourth of the votes cast in the election. Shortly afterwards, his appeal was turned down by the higher courts and he was imprisoned in Canton for ten months. By the time he was released the War was over. Resuming his activities in the Socialist Party, he organized and led the May Day demonstration in 1919, in which forty thousand Cleveland workers participated, including fifty A.F. of L. unions. Cleveland police and Ohio state troops attacked the demonstration with fire arms and tanks. In the street fighting which followed two policemen were killed. The police retaliated next day by wrecking the Socialist Party headquarters. This demonstration led to an increase of the party membership and of Ruthenberg’s reputation as a clear-headed, courageous leader.

That was the year the Socialist Party split on the question of the Bolshevik Revolution and the Communist International. Out of the Party’s left wing, which Ruthenberg helped to organize, there grew two separate communist parties. The government’s reply to the beginning of the communist movement in America was a series of raids on both parties in all sections of the country. Eventually Attorney General Palmer boasted that ten thousand workers were arrested in those raids; four thousand of them were in prison at one time. Leaders of both communist organizations—among them Ruthenberg, who was now in New York—were indicted under various “criminal syndicalism” and “anarchy” laws. This mass terror against the revolutionary workers launched by the democratic and idealistic Woodrow Wilson in the interest of the propertied classes had its effect: the young communist groups were crippled. They were compelled to organize an underground movement in which Ruthenberg played a leading role. Illegal life cut the two parties off from the mass of American workers; they became sectarian and sterile; their chief activities were internal party propaganda, conflicts between the two parties, debates about abstract theoretical points. Ruthenberg was among those who favored bringing the communists into open contact with the workers. He had begun to elaborate plans in this direction when he was put on trial under his New York indictment, convicted, refused bail and imprisoned in Sing Sing. During his imprisonment, the two underground parties united and by the end of 1921 organized the open Workers (Communist) Party. Shortly afterward, Ruthenberg was released from prison and the legal party made him its secretary.

This was the abstract picture I had of Ruthenberg when I met him in the fall of 1922. I was surprised to find him a tall, suave, handsome man, under forty, dressed in neat grey tweeds and a white starched collar. There was no “proletarian” pose about this proletarian revolutionary, that is, nothing bohemian. His desk, facing a window that looked out on Broadway and Eleventh Street, was orderly, as was the bookcase in which he kept the writings of Marx and Lenin. His long narrow face with its large forehead and prominent nose was fair and pink; when he smiled his bright blue eyes became narrow slits. I never heard him raise his voice in conversation; he always spoke calmly and methodically. On several occasions he explained the Communist Party to me. At my request he wrote an article on the subject which I published in the Liberator, In his article, Ruthenberg said:

“In the three years that have passed since the open Communist convention of 1919, the Communist movement in this country has undergone a transformation…It does not expect to convert the workers to a belief in the Soviets and the Dictatorship of the Proletariat by merely holding up the example of European experience. Its campaigns and programs of action are based upon the actualities of the life of the workers in the United States.”

The Party was becoming realistic. It was a section of the international revolutionary movement operating on the national terrain out of which it sprang, in which it was rooted. Just now it was agitating the slogans of working within the conservative trade unions, of organizing a united front of the workers, a Labor Party in the United States.

Partisan Review began in New York City in 1934 as a ‘Bi-Monthly of Revolutionary Literature’ by the CP-sponsored John Reed Club of New York. Published and edited by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, in some ways PR was seen as an auxiliary and refutation of The New Masses. Focused on fiction and Marxist artistic and literary discussion, at the beginning Partisan Review attracted writers outside of the Communist Party, and its seeming independence brought into conflict with Party stalwarts like Mike Gold and Granville Hicks. In 1936 as part of its Popular Front, the Communist Party wound down the John Reed Clubs and launched the League of American Writers. The editors of PR editors Phillips and Rahv were unconvinced by the change, and the Party suspended publication from October 1936 until it was relaunched in December 1937. Soon, a new cast of editors and writers, including Dwight Macdonald and F. W. Dupee, James Burnham and Sidney Hook brought PR out of the Communist Party orbit entirely, while still maintaining a radical orientation, leading the CP to complain bitterly that their paper had been ‘stolen’ by ‘Trotskyites.’ By the end of the 1930s, with the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1939, the magazine, including old editors Rahv and Phillips, increasingly moved to an anti-Communist position. Anti-Communism becoming its main preoccupation after the war as it continued to move to the right until it became an asset of the CIA’s in the 1950s.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_partisan-review_1936-02_3_1/sim_partisan-review_1936-02_3_1.pdf