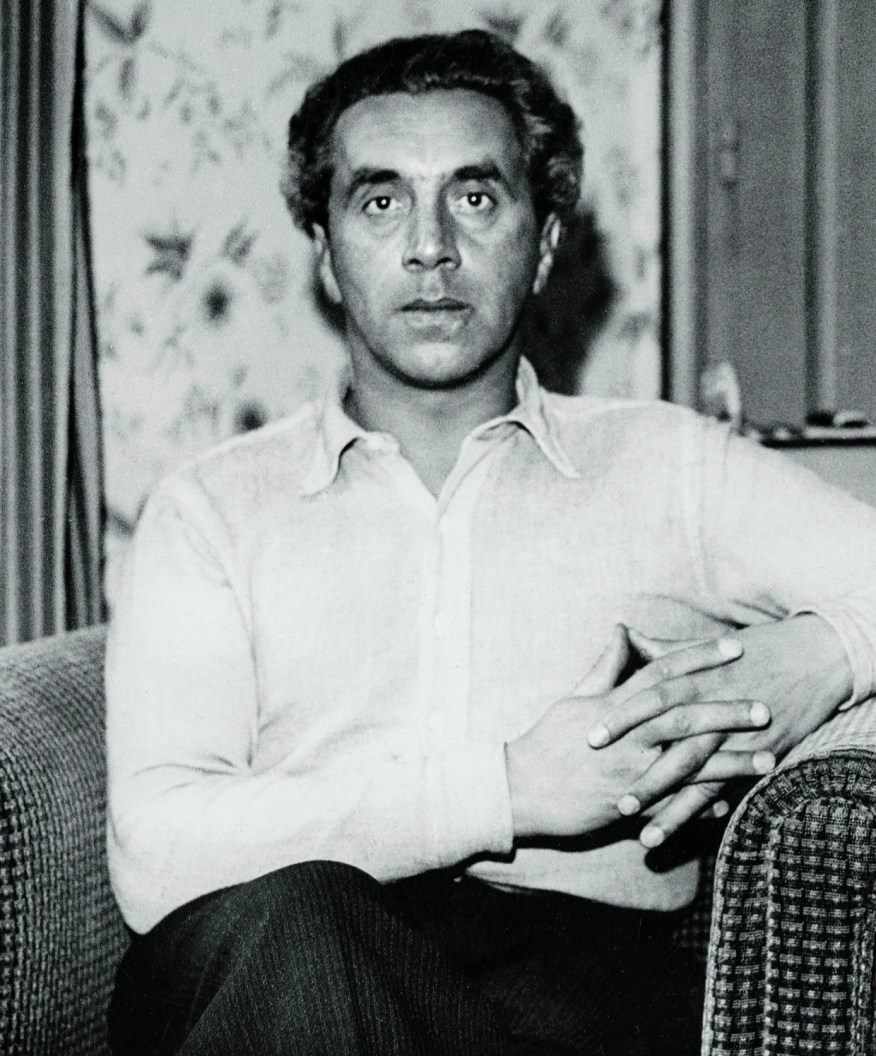

Ernst Toller, the great German expressionist playwright and revolutionary–the president of Bavaria’s six-day Soviet Republic in 1919–was an exile in New York City from Nazi barbarism when he took his life on May 22, 1939. Less than two weeks before he sent this anti-fascist defense of culture and human dignity to the New Masses.

‘The Last Testament of Ernst Toller’ from New Masses. Vol. 31 No. 11. June 6, 1939.

Less than a fortnight before his death, the great German anti-fascist writer gave to New Masses his last challenge to fascism in the following words.

WE, VICTIMS and witnesses of a flood already devastating Europe and threatening the other parts of the world, are asked: “How can emigrants do their share to defend the threatened culture?”

By culture we mean not only the amount of great creative productions of art, literature, and science; we mean as well the features of everyday life, the relations within the community and the nation and the moral ideals regulating them.

Though they may differ nationally in language and expression, in custom and habits, there is one root common to all the cultures of the occident: humanity.

Humanity is pouring from the sources of religions, it has grown from the perceptions of the sages, from the feelings of those who loved deeply. But its law did not come to universal prevalence until centuries and millenniums passed by. Today the dictators deny this prevalence in favor of the glorification of one tribe.

To us dignity meant: freedom of the individual; justice; his claim to a suitable development; compassion–the capacity to be susceptible to his fellow creatures’ sufferings. Fascism, however, is the foe of freedom, justice, and compassion. The martial fitness of man decides his usefulness, justice becomes club-law, compassion contemptible and ridiculous. Fascism makes the lie truth, hatred virtue, murder a necessity. For it does not respect anything, neither man’s happiness nor his sorrows.

Those men and women who resist dictators, and who are striving to keep intact the legacy of their culture and to enrich it by new perceptions and new creative productions, are persecuted and extinguished. Through exile they save themselves and their dignity. The German emigrants of 1933 are the successors of those fighters of independence, those Heines and Boernes, Wagners and Marxes, Herweghs and Schurzes, who in the nineteenth century–1819, 1830, 1840, and 1848–had to flee from Germany to escape tyranny and who, in exile, as representatives of their country enriched not only the culture of their fatherland which had ousted them, but also the culture of their guest-countries.

Richard Wagner’s The Ring of the Nibelungs, Heine’s most beautiful poems, Marx’s most important work were created beyond the German borders, in exile.

No matter if his name be King Frederick William IV or Adolf Hitler, the dictator’s eternal hatred gives evidence of clear and justified fear of the intellect. For the intellect is fearless and therefore a dangerous opponent. He who has overcome fear has overcome the dictator. That is true for the individual, today it is also true for states.

The democratic countries have received the emigrants with hospitality for which we feel profound gratitude and which proves that human solidarity is strong and alive. The same ideas, dear and sacred also to us, live and work in these countries. We have known and loved the work of their great men before they gave us shelter. The works of Shakespeare, Moliere, Tolstoy, Whitman, Zola, Ibsen, Byron, to name only a few, we have always considered our legacy of culture, riches belonging to all of us.

Such mutuality, though it does not relieve exile of its hardship, eases its bitterness. It is hard for writers to live in countries where their language is not spoken; they, who necessarily should listen to the audible and inaudible words of their people, hear only foreign sounds, the finest inflections of which remain inaccessible to them. Not to mention their difficulties in making both ends meet, pressing hard on so many of them. (Let me thank here our American friends who enable the American Guild for German Culture to assure the existence and thus the capacity for creative work to numerous writers, both known and young ones.)

Comparing the emigration of the nineteenth century to the emigration of today, we see one striking difference: in those times the emigrant could fight his dictatorship as poet and as soldier, as George Herwegh did at the head of a German legion. Nowadays the dictator is very often, even outside his country, so very powerful that booksellers no longer dare to offer books written by the exponent of the spirit banished by the dictator, theaters to perform his works, art galleries to exhibit a free painter’s pictures.

However, our emigrants as opponents are equal in rank to the German tyrants. Let Mr. Goebbels attempt a thousand times to offer the world an enslaved literature written in German, the world is reading the productions of the emigrants, because it has an inkling of these emigrants’ battle to save the Germany of humanity, which has been so great and admirable a part of the Western culture–and will be so again one day.

In spite of his hangmen Mr. Hitler cannot prevent a dangerous specter going about in Germany: the voice of the outlawed writer. This voice is so powerful that Hitler cannot drown it by the screams of his rage; sometimes it overpowers him, when the “Fuhrer” is telling his fettered people what we free ones are thinking and writing.

How can emigrants do their share to defend the threatened culture? The dictator was able to burn their books, to sequestrate their goods, but he could not rob them of the language of Goethe and Hoelderlin. Also, he could not rob them of their belief and their certainty that there are millions inside Germany who are conscious of their degradation.

The threatened culture can only be defended if all those who were fortunate enough to escape slavery devote themselves faithfully to their language, brand courageously and truthfully the treason against humanity, and fight barbarism wherever it threatens.

But this is not enough.

The threatened culture can be saved only if the subjugated nations keep alert the desire for freedom, justice, and human dignity and if this desire becomes so elementary that the desire turns into will and will into action.

ERNST TOLLER.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1939/v31n11-jun-06-1939-NM.pdf