In the decades-long struggle to bring the union into the rubber industry, every strike was a learning experience for the bosses who developed one of the most refined anti-union machines in capitalism.

‘What About Rubber?’ by H.E. Keas from Labor Herald. Vol. 2 No. 5. July, 1923.

“THESE are stirring times in the rubber industry, times of rapid progress and change calling for initiative, imagination, foresight, knowledge, judgment and poise on the part of all engaged in it. Conditions and methods no sooner become established than they are revolutionized by altered conditions of supply and demand, improved processes and machinery, and the application of rubber to new uses.” So reads the opening statement on the “publicity page” of the India Rubber World, for May, 1923. And the rubber barons, for whom this journal speaks, may well call these stirring times, especially as regards the profit side of the ledger. The golden pots at the end of the rubber rainbow are open for them. But what this means for the thousands of workers employed in the “gum shops” is a vastly different story.

A billion dollar industry! So reports A.L. Viles, General Manager of the Rubber Association of America, Inc., the “One Big Union” of the rubber barons, in a statement to the trade issued from New York, April 2:

“Statistics based upon reports to the Rubber Association from manufacturers in this country show that the sales value of rubber products in 1922 amounted to $906,178,000. This volume of business indicates not only the remarkable recuperation of the rubber industry since the nation-wide depression of 1920-1921 but further the great development and importance of the industry today.”

Rubber Barons’ Strong Organization

In line with the general upward curve of business conditions, a comparison of the two six months’ periods of 1922 shows an increase in the number of workers employed in this industry from 110,104 to 146,330 and an increase in sales of approximately $90,000,000. And then, with unprecedented profits in sight, living in the luxury the ancient kings of Babylon, Greece or Rome never knew, these rubber barons in their West Hill palaces in Akron, Ohio and other rubber centers have not only the unmitigated gall to cut the wage rates of the workers slaving for them, but threaten further cuts and offer them a bonus! Speed, evermore speed! For more production and greater profits! Speed-up until the workers break under the terrific strain–to fill the coffers of their masters.

These rubber barons are no pikers when it comes to organization. Their “Rubber Association of America” is so highly departmentalized and so efficiently supplied with committees that it would warm the heart of the most enthusiastic industrial unionist who ever drew a breath, could he turn such organization over to the workers who made it possible–but the rubber barons beat him to it, for under the inevitable pressure of economic evolution and through fear of the rising power of the working class, capital usually takes the first step. But this, in turn, will compel the workers to organize likewise.

Sweating the Rubber Workers

Although there are hundreds of rubber plants making different products located in various parts of the country, the chief rubber center of the United States is Akron, Ohio, where there is produced 60 per cent of the rubber goods of the country. In this city of 208,000 people, there are approximately 40,000 workers engaged in thirteen rubber manufactories. The census of the Akron Chamber of Commerce for 1922 gives the total number of workers employed in Akron factories as 49,708. One can easily understand gained the appellations “Rubber City” and “one the reasons why this northeastern Ohio city industry town” when one compares the figures cited above.

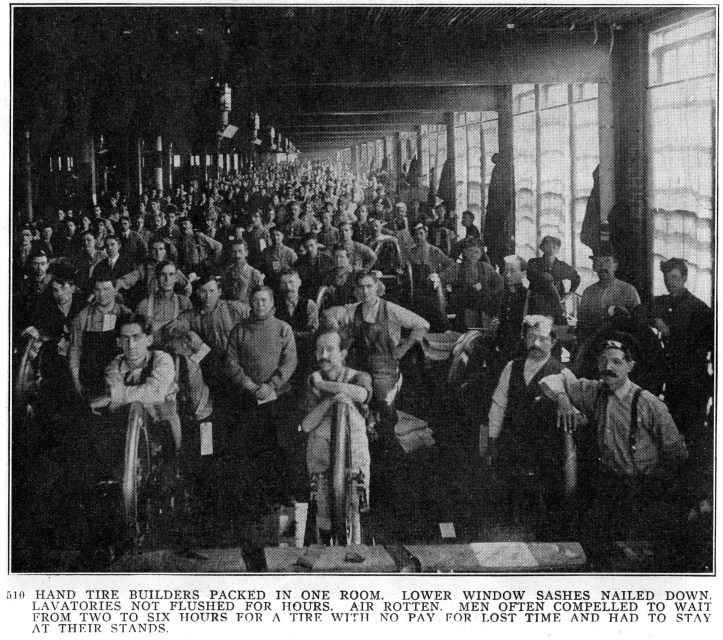

Among the big companies located here are the Firestone, the Goodrich, the Goodyear and the Miller; one of them, the Goodyear, alone employs 15,000 workers. This latter company is the headliner when it comes to speeding up the workers. On one day in April, the Goodyear Akron plant turned out 48,592 automobile tires. The previous Akron record had been 35,780 tires on April 1, 1920. The 1920 record was made by 31,000 employes, while it took the work of only 14,950 to set the 1923 mark. These figures need no further comment!

While it is true that the Akron rubber workers can earn as much as $7.00 per day in some departments, it is only by working at nerve-racking pace that they can do it. Formerly two-men machines were used but at the present time machines manned by only one operative are doing the work which used to require the attention of two. Under the speed-up system now in use, seven men are now compelled to do the work that nine men did but a short time ago. Wage cuts have been made in several departments, but a bonus of 10%, out of the goodness of heart of the fatherly rubber barons, have been given the poor deluded workers instead. It is required of them that they must increase the number of pieces on production in ever-multiplying ratio to get that 10% bonus “lolly-pop.” Meanwhile the dear rubber barons are advertising widely in small-town newspapers all over the land for young girls, who when they arrive will take the places of the suckers who are smacking their lips over that 10% “lolly-pop.”

How They Fight the Unions

Another scheme put over on the workers is the “pooling system.” Workers are occasionally started in different departments at the lowest rate as inexperienced employes, then worked up as they gain more experience to where they can earn about $6.50 to $7.00 per day. When they reach this point they are transferred to another department, under the subterfuge that there is a slackening up in demand for the work they had been doing, and must again start at the lowest rate in the new department as an inexperienced operative on that particular task. Verily, Machiavelli had nothing on his modern counterpart, the rubber baron!

Chloroform! This one word aptly expresses why the rubber workers are as yet practically unorganized, why they are misled by bonus and speed-up systems with hardly a vestige of class-consciousness as a wage-earning group, producing untold profits for their employers while they accept the crumbs. One of the many subtle schemes engineered by the rubber companies to keep their workers from organizing labor unions and trying to do things for themselves, is the “Industrial Representation Plan” of the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company, its chief exponent being Paul W. Litchfield, Vice President and Factory Manager for this concern. Established in March of 1919, it was hoped such a plan would forever sidetrack the attempts which their employes might make toward real workers’ organization. The “Industrians” are those employes who have reached 18 years, are American citizens, understand the English language and have had a six months’ continuous service record in the Goodyear factory immediately prior to election. Note the subtly-injected division of native worker as against foreign-born so carefully fostered by the American employing class and “open shoppers” who hope that such artificial devices will keep their wage-workers divided.

Within the scope of this article it is impossible to go into details regarding the various ramifications of this company union. Suffice it to say that the rubber barons in the Goodyear keep it well oiled and working so smoothly that the worker has no real voice as to the conditions under which he works. The court of last resort is the management and above them the arbitrary will of the owners. Lolly-pops! The word is more apt the further one analyzes the various smooth schemes of these West Hill parasites and their menials who carry them out.

The rubber barons learned a lesson from the Akron strike of 1913. Although short in duration it was bitterly fought out by the workers and for a considerable time seriously crippled production in the rubber industry. And what did these students of “hocus pocus” devise to prevent a possible second occurrence? Nothing less than a “Flying Squadron!” In a Goodyear pamphlet under date of March 1, 1913, they briefly survey the extent of the strike and issue an appeal for the support of their “loyal” employes to again build up their personnel. Under date of April 15, 1913, less than two months after the termination of the strike, there appeared in a small paper published for the employes in the plant, an editorial notifying their employes of the formation of an organization of specially skilled workers who were to be trained to do work in any of the departments so as to “balance up the production” and keep it “uniform.” Only the so-called “best” men were to be taken into the “Flying Squadron,” a strike-breaking force which is available at all times and for any department. From a few hundreds when it was first organized, this squadron now comprises several thousands of “loyal” workers ready to do the bosses’ bidding in case of trouble.

Rubber Workers Must Organize

The Akron rubber workers have little or no organization worthy the name. Although a few hundreds joined the A.F. of L. in an organization drive conducted during the walkout of the Goodrich workers in the cord tire department in January of this year and who have been given a Federal charter and an additional few scattered workers organized in the machinists’ union, electrical workers, stationary fireman and oilers, etc., there is absolutely no organization in the shops.

Of late, the Akron workers have become discouraged and disgusted with the methods of the leaders in the Central Labor Union and the special A. F. of L. organizer stationed there, so it is said, “to keep the radicals from getting control,” and they are beginning to demand action toward efficient organization for the rubber workers and an immediate breaking away from the pussyfoot policy of the reactionary leadership now in control. What the developments will be will depend upon the courage and energy of the rank and file and their determination to fight it through.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v2n05-jul-1923.pdf