The Second Klan emerges as part of the Red/Black Scare with Art Shields reporting on the assault on Harold Mulks, a lawyer for the Oil Workers’ Industrial Union organizing in Shreveport, Louisiana.

‘The Return of the Klan’ by Art Shields from The Messenger. Vol. 4 No. 2. February, 1922.

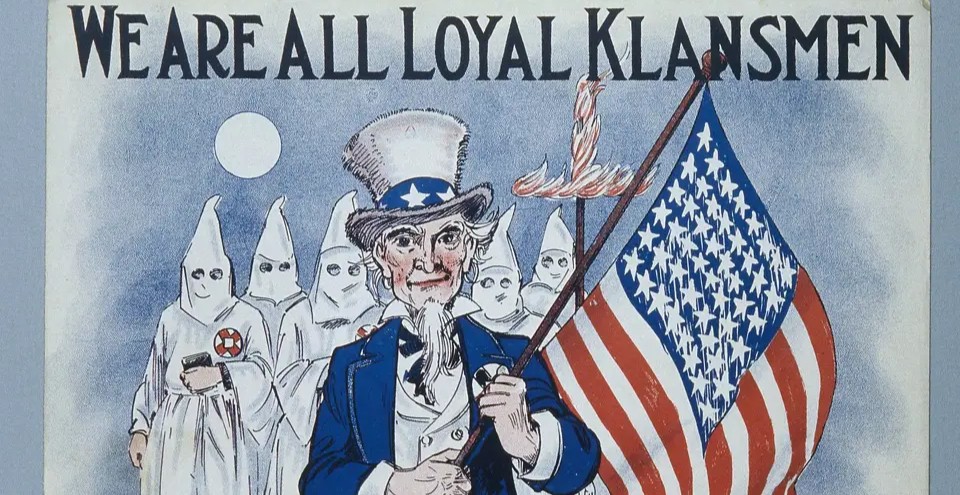

ACCORDING to the monthly survey of the state of civil liberty in the country by the American Civil Liberties Union, the unlawful, savage practices of the Ku Klux Klan are on the increase. Negroes, labor leaders, A.F. of L. and I.W.W., Catholics, Jews and foreigners are being kidnapped, tarred and feathered, flogged and beaten, branded, chased out of towns, lynched, burned and murdered promiscuously, without interference by the local or state authorities. In most cases the local authorities confess their helplessness before this murderous gang of night-riders.

So that the so-called Congressional investigation of the Klan was a fiasco–a mere white-wash! We never had any faith in it. Most investigations fizzle out. Too much deference was shown the “sob” stories of the Imperial Wizard. He threw fits for the fun of it and the naive or hypocritical committee fell for such transparent legerdemain.

We carry the following release from the Federated Press as proof of our charge that the Ku Klux Klan is reviving:

By ART SHIELDS (Federated Press Staff Correspondent) Chicago.

In spite of the frightful rawhide lashing he received from the masked mob near Shreveport, Harold Mulks, the young attorney for the Oil Workers’ Industrial Union looks full of fight as he sits in his office at 111 Monroe Street, Chicago, and lays out plans for a joint investigation by liberals and labor unions of the Louisiana atrocities.

“The Ku Klux Klan reigns unchallenged in that barbarous state,” said Mulks to a Federated Press representative, “and it is doing the will of the great oil interests. The beatings which organizers and their attorney have received are just the beginning of a policy of terrorization unless sharp and vigorous action is taken by lovers of justice.

“I have every reason to believe that the police authorities of Shreveport worked hand in hand with the Klan members in my kidnapping case. The police authorities were the only ones to whom I had given my address–at their request. After I was threatened the Monday night before the kidnapping they refused to give me any protection. I put the case up to Assistant District Attorney Crane. He advised me to see the mayor, but Mayor McCord ridiculed my story and told me I had nothing to fear.

Mulks said that a certain city detective with a checked suit was always in his vicinity, and apparently acted as shadower for the Klan. This man was a witness in the case of the organizers sentenced to the Parish farm, whose case Mulks had come to Shreveport to appeal. The sleuth was standing in front of the car when the kidnappers carried him out of the hotel.

All the extremes of Southern courtesy and brutality were illustrated in the action of supposed Klansmen, said Mulks. When he was first threatened in front of his hotel Monday night, January 9, it was by a well dressed man, with a soft drawling voice. The man, followed by two others quietly told him that they wanted no trouble, and that they and the 2,000 “best people” of Shreveport would all be very much pleased if he would drop the case of the I.W.W. men.

“You know we have some 40 per cent n***s down here, and a lot of Jews,” said the man, “and sometimes we have to just take the law into our own hands in dealing with them.

“Now we know you are a smart man and have traveled around a lot, but we don’t want you to travel around here on this case. There are 2,000 of the best people of Shreveport behind us, and you can’t go ahead with the case.

“Well, I know my rights as a lawyer defending my clients,” said Mulks. “I don’t care if there are two or two thousand. I’m here and I’m going to stay.”

Mulks notified the authorities at once and went ahead with the case, appearing in court next morning. The other side then had the case postponed another week, and Friday night the gang of fifteen masked men suddenly rushed into the lobby of the Hotel Yokem and began beating him with their fists. Thinking they were going to kill him there Mulks knocked one of his assailants down in the effort to break through to the door, but they picked him off his feet and carried him into a large closed door. Five men piled into this car, the rest following in two more machines.

Rushing past the police station, ninety feet away, they went on into the prairie night, cursing and threatening their victim every minute.

“Ah, you dirty–,” they would snarl. “We’ll cut you to pieces. You and your Jew friends, we’ll clean you up and make you wish you had gone back to Russia.”

“Yes,” another would say, “he’s another one of those Catholics–we’ll teach him what the Klan can do.”

Another would denounce him as a friend of the Negroes and another as an I.W.W., all in a confused way that showed their utter ignorance, Mulks said.

The Ku Klux Klan, which Shreveport reports say these men belonged to, hates Jews, Catholics, foreigners and labor unionists impartially.

Twenty miles west of Shreveport the cars stopped and Mulks was taken out and his shirt stripped off, then he was thrown over a log and held by five men, while three others lashed him with rawhide whips over the back and head.

Faint from loss of a quart or more of blood Mulks was helped on to a train that stopped at a junction not far off and put in charge of the conductor, who was ordered to hold him till the borders of Texas on peril of his life.

The conductor proved to be a decent fellow, bathed Mulks’ wounds and told of the spell of terrorism under which the union men of that part of Louisiana lived. The district, he said, was known for its brutality. He himself had seen some twenty lynchings of Negroes who were hanged, burned to the stake and shot.

Some of these Negroes were lynched as the result of economic causes. Unions of skilled craftsmen are frowned on, the conductor said, but the violent persecution comes when unskilled workers, black or white, attempt to better their condition.

After three days in a Dallas hospital, Mulks came on to Chicago to organize support for an investigation of the Louisiana persecutions. He is an unusually sturdy man physically so escaped internal injuries as a result of the flogging, but his back is scarred, and part of his head is shaved and plastered.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both W.E.B. Du Bois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/02-feb-1922-mess-RIAZ.pdf