The editor of Southern Worker travels down the Savannah Highway and meets a family of activist share-croppers as Communism appears in the cabins of the Deep South.

‘Awakening in the Cotton Belt’ by James S. Allen from New Masses. Vol. 8 No. 2. August, 1932.

It was July. The crops were being put by. The cotton plant stood almost a foot high, in long freshly chopped rows. Barefooted Negro men and boys were plowing on the larger plantations. All available hands, not busy with cotton, were on the planters’ vegetable patches chopping the earth that had once been black. The sun was hot. Only those who could neither walk nor toil—the very old or the very young—could be seen about the cabins. The countryside was at work.

On the old Savannah Highway a chain gang was also at work. Two white guards with loaded Winchesters and revolvers at their belts, watched the row of Negro prisoners, in stripes and chains, shovelling dirt from the gully. In the slow steady rhythm of the Southern sun the men and boys shovelled out their sentence.

All is quiet on the domain, you would say, just passing through. You see the peaceful-looking cotton patches and the peaceful-looking Negroes at work on them. The mill at the creek is grinding out meal from last year’s corn. You see X…in the heart of the South Carolina cotton country, a peaceful-looking town—if you would call it a town—with its railroad siding, the one general store and the few cottages. If not for the cabins on the road coming up, you would say that the country looks even prosperous. The crops are progressing fine. Everything is in its place as it should be—the Negroes on the patches, the landowners in their mansions and the chain gang on the road. King Cotton’s beard may be a little grayer, but he still sits on his throne—from the looks of things.

We turn off the highway into a dirt road, pass a field of green cotton plants on which there is still no trace of white, and come within view of a three-room cabin. It is larger than usual, but so are the cracks between the crude white-washed boards that form the walls. No shingles cover the board roof. A sixty-five-year-old Negro cropper, his wife, seven children and three grandchildren call this home.

The unemployed son has come from Greenville, bringing a white man with him. We arrive at the dinner hour, when the old man is resting on the porch and his sons are returning from the plowing. The youngsters venture timidly forth to have a better look at the approaching car and then retreat when they see a white man at the wheel. The old man is outwardly unconcerned and shows no trace of emotion as the car draws near the porch and he recognizes his son. We hid the car in the back of the cabin—a strange car and still more a strange white man arouses suspicion in this country. Everyone stands at a distance as Bill approaches his father. The father eyes the son quizzically. A sudden homecoming can bring no good. And there is a strange white man.

“May God bless you, son.”

The mother stands in the doorway, a thin emaciated woman, with back humped from years of cotton picking and hoeing. A warm smile and a nod to her son, no hugs, no caresses.

Bill introduces me.

“He is one of us.”

I extend my hand. The old man hesitantly, questioningly offers his toiler’s hand. It remains limp in mine. He is not quite certain when to withdraw it. It is probably the first time he has ever shaken hands with a white man.

“Have a seat, boss.”

The son is impatient with his father. Bill has worked in the city for a number of years and partaken of the new vision offered him by the Communist movement, which has found permanent roots among the Negro workers of the South. He is representative of the new Negro worker, with one foot still in the soil, who no longer cringes before the white man, the “boss” and the “master.” It is this new Negro who, aroused to full self respect and unbelievable militancy by the Communist Party, has caused wide-spread alarm among the upper classes.

“He is not a boss, father. Among our people he is a comrade, just like you and me. He is one of us, and that’s what comrade means.”

The old man takes the lesson from his son with an apologetic smile.

“That’s the way we are accustomed here, boss,” he says, “and I reckon it’s hard to break from.”

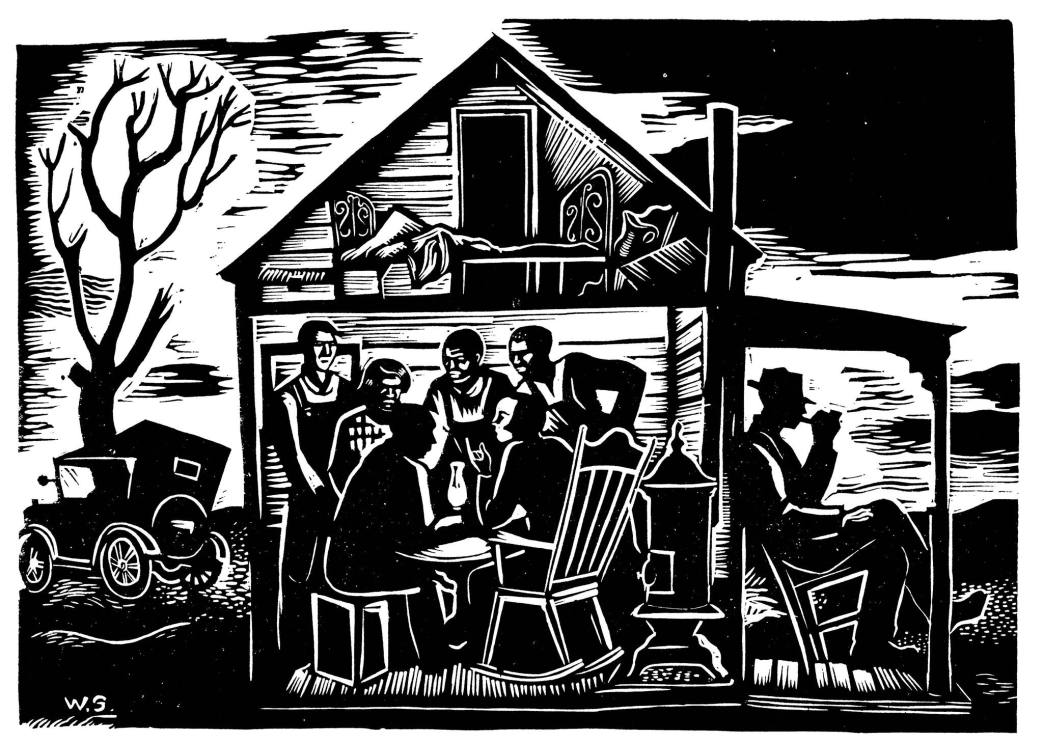

Over the rough board table in the kitchen the words “boss” and “master” begin to wear off. The old man, Bill, the 18-year-old son and myself are having dinner together—from the same table, from the same dishes. There are huge spaces between the floor boards, carpeted with flies. One of the younger daughters, barefooted and in tatters, stands by the table and drives flies from the food with a fan. The meal consists of hot cakes, corn bread, hominy, lard gravy and fatback in honor of the guest. The younger son hesitates to take another piece of fatback, but the old man encourages him.

Old Man Johnson is a cropper. He farms 25 acres of land, 15 to cotton and 10 to corn. By tacit agreement with the landowner, he is to turn over half his cotton and corn at the end of the season for the use of the land. From the remaining half the landowner is to take his payment for the food he has advanced during the season. Johnson may not take his crop to market and sell it himself.

Mrs. Johnson explains from the stove:

“Last year all we had was some corn after the pickin’. We picked our cotton and were cartin’ it in and there was the boss on the road. ‘Bring it all around to my barn where it’s dry,’ he says. We took in the peas and potatoes—we had them last year—and there he was again: ‘Around by this way, Alec, up to my barn. You got no place to keep it.’ If it wasn’t that I just dumped a good part of the corn right in my kitchen before the boss had a chance to see, we wouldn’t have had even that for the winter.”

The old man points to his barn through the doorway. The walls have given way on two sides and the roof forms a crazy triangle with the ground.

“It’s been that way all year and will rest that way next year. The boss says he wont fix it and wont let me neither. It’s that way on all the farms. Then when we’re taking the crops in he can say to bring it all over to his barn, where it will be dry—and we’ll never see it again.”

There is great hatred for “the boss.” He is the son of the owner, and overseer of a dozen of the smaller plantations in the section, each having about five or six cropper families, and of two large plantations employing about 100 farm laborers each. The planter is an old man, suffering from some chronic ailment that does not permit him to get about. His son is the whip in his hand.

Old Man Johnson has neither plow nor mule. He gets the use of plow and mule from a small white landowner down the road, in return for plowing his land. The sons do the plowing, two days on strange soil, one day at home.

The Old Man is chopping peas for Mr. T. All the Negroes, finished with putting their own crops by, are at work on the vegetable patches of the big boss. Old Man Johnson is sick, his back pains him. He chopped peas in the morning, but he fears the afternoon ahead of him under the hot sun. The old lady tells him to sit pretty, to just stay at home. Mr. T. Pays 25 cents a day for chopping peas. If someone does not report, his son stops around to see why. His word is law in this country.

A bell tinkles in the distance.

“They’re off to work,” mutters the old man. “Time for us to be going.”

He trudges wearily away down the dirt road after his two plowmen sons.

“And how do you manage to feed yourself and your children, Mrs. Johnson?”

There are the food advances from the planter. Every week $2.00 worth of food as follows: 12 pounds of flour, two quarts of rye, ten pounds of fatback, a pound of coffee, two pounds of sugar, 2 pounds of lard. This must feed the whole family for a week. There is no money in this peasant economy. Even the 25 cents a day made at chopping peas or cotton is paid in the form of food or credit at the general store in X…which is owned by the big boss. Every so often a cropper will stealthily sell a chicken, if he is lucky enough to have one, or some vegetables, if he was permitted to plant a vegetable patch of his own, and thus obtain a little change.

And for the winter? The part of the crop that is left after the landlord takes his—for the Johnsons the pig that they are trying so carefully to fatten on the limited amount of fodder and refuse. It may be that when winter comes the pig may no longer be theirs but resting in the barn of Mr. T to make up for that part of the debt not paid for by the cotton and corn. Mr. Johnson’s mule went the way of Mr. T’s barn last year when cotton sold at 10 cents a pound.

“And what will you do this winter, Mrs. Johnson when cotton sells at 5 cents a pound?”

The old woman shrugs her shoulders. All the winters of her life she has passed in this county and her mother was a slave to the parents of Mr. T. There were times when at Christmas, there was cash among the tenants, paternally doled out by the planters in a shy lock settlement for the year’s work. But there was none last winter and there will be none this year. Winter hovered like a voracious demon over the cotton country.

Old man Johnson, Bill and I hit over the back roads, away from the white men’s cottages, to visit reliable kinsmen and friends. Whole families of black people, laboring on the soil, many mouths to feed on starvation doles. Up near the mill there is the big plantation worked by laborers—men, women and boys—100 of them, at 25 cents a day for the men and 20 cents a day for the women, huts thrown in, with board at the plantation commissary out of the wages.

There is an ominous murmur among the Black Peasantry. Twenty-five cents an acre for chopping cotton—a full day’s work! And didn’t the three Williams kids chop seven acres of cotton for Mr. T in four and a half days and only get one dollar altogether for it? Can one expect more than 25 cents a hundred pounds for picking cotton, usually a source to be banked upon for some credit and cash for the winter months? And what will the winter be like? And what is to be done?

All this is only whispered after Bill has assured them that I am a different kind of a white man, one of them, a “comrade.” And Old Man Johnson had said:

“Let me tell you something about him. He ate with me at the same table and slept in my house. And we was just comfortable like his color and mine were the same.”

Then the mumbling becomes more intense, with veiled meanings and many questions. I am surprised at the evidence the croppers’ words and especially questions gave of the deep penetration of Communist propaganda into the very heart of the agrarian South, where, I am sure, Communist literature has never reached before.

In the heart of a wooded section we come across the chain gang camp. The gang is still at work on the road and the Negro trusty cook has no objections to our investigation. There is the bunk wagon, a steel cage on wheels, with eighteen steel bunks to which are chained 21 prisoners every night. In the middle of the wagon is a basin for refuse. The human cargo in the cage is wheeled from one place to another in the county to work on the roads. Differ with your landowner and the sheriff will take care of you! The domain of Mr. T is a petty kingdom, embracing some 300 cropper families, with its own courts of justice and laws of servitude.

At dusk, we take Old Man Johnson to see the doctor at X. I drop the old man and Bill down the road a bit, for it would not do at all to have themselves seen in the company of a strange white man. They knock at the back door of a cottage. The doctor, one of the retainers of Mr. T, spends a few minutes examining the old man in the barn—he would not permit a “n***r” into his house. He gives him some drugs and the account of Alec Johnson is charged three dollars for medical service to be taken out of the labor that sends pain shooting through his back.

Old Man Johnson, he of the older generation whose life touches at either end the struggle against an old slavery and the struggle against a new, does not accept his lot complacently. He is silent in the car as we drive him back to his cabin. But that night, in the circle of intense croppers gathered about his kitchen lamp come to meet the black man from Greenville with a new message and the white man who eats from a black table and sleeps on a black bed, he finds new uses for words out of the Bible to simplify the newer language of his son.

Two weeks later, when the crops were all put by, the landowners stopped all food advances to their tenants, until cotton picking time in September. For six weeks the black peasants, and the few white croppers of this vicinity, sat by without the regular weekly food supply while the cotton bolls opened under the hot sun. Is it any wonder that during this time, the Negro toilers of Sumter County found a new standard for the judgment of their fellows—is he with or against the Southern Worker?

When cotton picking time came Mr. T and his associates paid 25 cents a hundred pounds—50 cents for a day’s picking, from sun up to sun down. And Mr. T’s storehouses were overloaded with the bounteous crops and his barns saw many new animals.

When the fields of the cotton country were hardened with frost, Old Man Johnston continued to mix his biblical idioms with the newer language of young Bill, and new methods for fighting starvation were being evolved.

Fearing fraternization the United States War Department disbanded and disarmed the two regiments of Negro infantry and the two regiments of Negro cavalry stationed in the South and distributed the black soldiers among the white camps to act as labor battalions. Counties in the Alabama Black Belt passed new criminal syndicalist laws. The Southern press peddled rumors of “Negro uprisings.” Deep-felt alarm pervades the white upper classes and “Uncle Toms” of the South.

A new spirit pervades the Negro masses of the South, stiffened by a thoroughgoing, although slow, transformation in the attitude of the Southern white workers towards their black brothers. The Georgia crackers are being replaced by revolutionary native white workers and even more rapidly are the “Bills” taking the place of the “Uncle Toms.” Camp Hill—its victories, its defeats, its mistakes—is becoming the property of the rural masses throughout the Black Belt, born and planted in the black soil by the city workers. Bill received his industrial experiences in the period of Gastonia and Scottsboro and returned to his home soil to impart its import to the Negro peasants. He carried back with him a vision of a liberated Negro land, stretching from Virginia to Arkansas like a sickle, and the unalterable conviction that the white revolutionary workers would not only grant their support for this struggle for the right of self-determination but would also be in the leading cadres.

The deep devastating misery of the crisis winter and the starvation summer in the South are engendering major struggles. The widespread boycott of cotton picking by both white and Negro toilers last autumn—they refused to pick cotton for 25 and 30 cents a hundred pounds—foretells new mass struggles at 1932 cotton picking and “settlement” time. Bill, Old Man Johnson, the white cropper down the road are forming a union for common struggle against starvation.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1932/v08n02-aug-1932-New-Masses.pdf