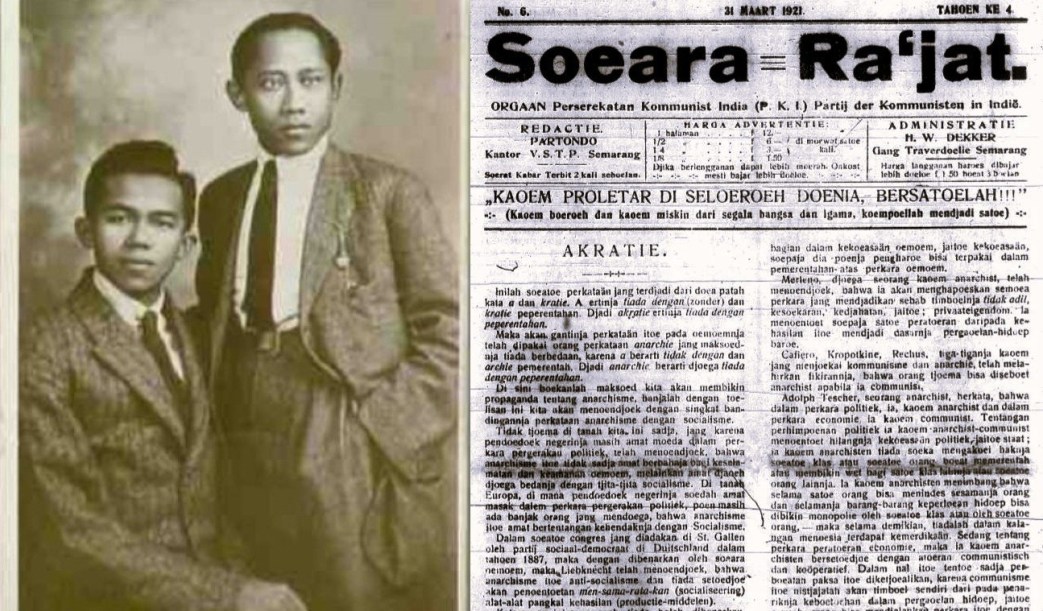

Indonesia, with the first, and for much of the 1920s, largest Communist Party in Asia, was also involved in genuine revolutionary struggle, complex and consequential. As such the country featured in 1928’s substantial World Congress discussion of the revolutionary movement in the colonies and semi-colonies. Kjai Semin, Darsono (Sami) delivered a valuable history of the movement, detailed and concise, co-report on what was learned, while Louis de Visser of the Dutch delegation spoke on the question from the metropole, while Indonesian delegates Musso (Mauawar) and Padi (I am unsure who comrade ‘Padi’ was) also added to the report. The PKI was among the most vital and influential of the early Communist Parties in a colonial country, or any country. Working in, and partially leading, the popular Islamic party Sarekat Rakyat, the PKI played a leading role in the mass rebellion that broke out against Dutch imperialism in 1926. In the aftermath of the insurrection, a mass wave of terror hit the Indonesian workers’ and anti-imperialist movement. The Communist International’s most substantial discussion of anti-imperialist colonial revolutions was held at the Sixth World Congress in 1928 shortly after those events and different, but similar events in China. I hope to transcribe the bulk of these informative and important discussions.

‘The Indonesian Revolution at the Sixth Comintern Congress’ from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 Nos. 74, 76, & 78. October 25, 30, & November 2, 1928..

29th Session August 14, 1928. Afternoon.

Co-Report of Comrade SAMIN:

Comrades, the Communist Party in Indonesia succeeded up to the rebellion in November 1926 to win the leadership in the national movement and to diminish very considerably the influence of the various national parties. The first mass proletarian attack upon Dutch imperialism in Indonesia, the general railway strike in May 1923, was led by Communists. The uprising in November as well as the uprising in West Sumatra in January 1927 were also led by the Communists. No other Party had such authority and influence among the broad masses of the people as the Communist Party.

This was by no means an accident and was not of a merely transitional character, as the reformists and Indonesian nationalists declare. I am sure that the good revolutionary traditions that prevail among the masses about our Party will be revived, notwithstanding the defeats we have suffered, and that our Party will once again be able to lead the masses against Dutch imperialism and next time to lead the struggle to a victorious conclusion.

Comrades, I think it will be difficult to find another country in which there is such a large number of various stages of development as will be found in Indonesia. Each one of the islands comprising what is known as Indonesia is on a separate stage of development. In New Guinea, where about 3000 comrades are in banishment, the ordinary population still lead a nomadic life and among them cannibalism is a common practice.

For imperialism and for the Communist movement the following islands represent the most important: Java, Sumatra, Celebes and Borneo. Of these Java is the smallest island and the most densely populated. In area Java represents only one-thirteenth part of Indonesia, but in 1920 the population was 35 millions out of a total population of 50 millions for the whole of Indonesia. According to present estimates the population of Java has risen to 40 millions. This density of population renders a rapid economic development of Java possible. The shortage of labour which hinders the rapid development of the “outer territories” as Sumatra, Borneo and Celebes and the other islands are called does not exist in Java. Another reason why Java has forged ahead of the other islands in her economic development is that, for example, in the year 1924 the exports of produce from the large agricultural enterprises in Java was three times as much as the combined exports of those of the other islands. The enormous rise in the price of rubber in the years 1925, 1926 and even in 1927 has changed the situation somewhat in favour of the outer territories.

In Java a tendency is observed for the exports of produce of native enterprises to diminish, whereas in the outer territories a tendency is for the time being observed towards an increase. In Java it is the big capitalist enterprises that predominate whereas in the outer territories, for example in Sumatra, peasant economy has still a future before it. Nevertheless, there are symptoms showing that even in Sumatra the position of the native farmers will be seriously menaced by the rapid increase in the development of foreign capital.

In 1925 the total exports of the outer territories exceeded that of Java. This was due to the heavy exports of rubber. In that year the price of rubber was extraordinarily high. This year, however, the price of rubber has fallen considerably, and it must be expected that Java will again occupy first place in the economics of Indonesia.

The disintegrating influence of the rapidly increasing investments of foreign capital in Java is affecting the system of the communal ownership of land.

From 1882 to 1922 the number of villages declined from 29,518 to 21,539 as a result of the merging of small villages with larger villages. Notwithstanding this merging of villages, the diminution in the number of the villages with purely communal land ownership and the increase in the number of villages with purely individual landownership can be taken as a clear expression of the great change that is taking place in the rural districts. This change is naturally accompanied by a process of differentiation among the peasantry, which means the impoverishment of the majority and the enrichment of a small minority of the peasantry. Between 1892 and 1902 the number of villages with purely communal landownership declined from 11,136 to 7885. This period marked the entry of the period of imperialism, of export of capital.

The development of foreign capital in Java has caused widespread impoverishment. Writing in “Handelsberichten”, H.L. Haigton, a representative of the Dutch importers in Indonesia, says the following about the impoverishment of the Indonesian population:

“In order to have a clear idea of the unfavourable conditions that prevail for imports account must be taken of the low purchasing capacity of the natives employed on the plantations, whose daily wage is about equal to the hourly wage of a Dutch worker. With a few exceptions there are hardly any native capitalists. The conditions of life of the Javanese might be described as an hand to mouth existence!”

After the uprising “De Courant”, a liberal Dutch newspaper, in an article entitled “Unrest and Prosperity” had to admit that the so-called poll-tax, which the population regarded as very unjust, would now be repealed. But even the other taxes that the Javanese peasants had to pay were very heavy burden upon them. The paper wrote:

“A section of the rural population of Java (we hope that it is only a small section) is so overburdened with taxes and is therefore compelled to live on such a small income that, in the event of a revolt against the State, it has nothing to lose, except the life of poverty, care and deprivation, a life that the majority of us would attach little or no value to. It is no wonder, therefore, that the Communist leaders have won thousands of adherents, particularly in the rural districts, who were prepared to conduct armed warfare against the representatives of the State.”

This means that the masses of the Javanese people live under conditions that the European comrades could hardly conceive of. An official report of an investigation into the burden of taxation of the population of Java showed that the taxation per head in Java represented 42.86 gulden, or 71 marks per annum. Although the cost of living is not very high in Java, nevertheless, the amount left to the peasants after this sum has been paid is not sufficient to cover the barest needs. And yet the above figures rather understate the case than otherwise.

It is quite impossible to expect that the conditions of life of the masses of the Javanese people can be improved under the capitalist system. On the contrary, we must expect that their conditions will become worse, because the government is placing the overwhelmingly greater part of the taxes upon the impoverished population. This is shown from the following figures. In 1927 private export amounted to 809,234,745 guldens and private import amounted to 563,016,432 guldens, so that exports are about half as much again as imports. The import duties in that year, however, amounted to 28 times as much as the duties on exports. This means that an extraordinarily heavy burden of indirect taxation is imposed upon the masses of the people, for the taxes are imposed almost exclusively upon goods consumed by the people whereas no duties are imposed on imported machinery, etc. The exports of the produce of big capitalist enterprises are duty free.

This ruthless taxation policy inevitably leads to the impoverishment of the people in Java and compels them to migrate to the other islands like Sumatra and Borneo where, owing to the shortage of labour power, the development of big capitalist plantations is not so rapid. About 60,000 Javanese peasants emigrate yearly in this way.

The process of class differentiation set in only after the outbreak of the war. This differentiation proceeds in one direction towards the creation of a growing landless and, therefore, radically minded peasantry, and in the other direction towards the creation of a thin stratum of prosperous peasants, who, however, are not sufficiently strong ideologically to influence the other sections of the population.

The process of mass impoverishment is, in the final analysis, the result of the policy of Dutch imperialism which is commonly known as the policy of the “Open Door”. This policy means that foreign capital is allowed to enter Indonesia as freely as Dutch capital, i.e., no protection is given to Dutch capital. The object of this policy is to play off the big powers against each other and in this way to make Holland’s possession of Indonesia more secure. But the effect of it is that Indonesia is becoming industrialised with exceptional rapidity, particularly in the case of Java, which in its turn results in the rapid rise of a proletariat which literally has nothing to lose but its chains and is therefore very revolutionary.

Sumatra. This island has an area 3.6 times that of Java, and has a population barely amounting to 6 millions. Sumatra is the land of the future for capital in Indonesia. Peasant farming and small industry predominates here. The “Open Door” policy will have the same effect here as it had in Java. In 1925, owing to the high price of rubber, a small section of the population in Southern Sumatra rapidly became rich. The rubber plantation industry has excellent chances for expansion because there is plenty of free land, but labour power is insufficient. But capital attracts labour power from Java, China, and partly also from India. On the plantations about 300,000 indentured labourers are employed, working under most horrible conditions. For years already the politicians have been striving to introduce a law prohibiting indentured labour, because the conditions of these plantation coolies are no better than that of slavery. So far, however, these efforts have not met with success.

In addition to plantations there are coal and gold mines in Sumatra as well as modern industries for the winning of oil. Railways and roads are being laid down in order to accelerate the economic development.

In Sumatra the Communist Party has considerable influence among the peasantry, because the peasants are discontented with the government’s taxation policy. Owing to the shortage of labour power, the peasants, in addition to their heavy burden of taxation, are compelled also to put in a period of enforced labour on road building.

In Indonesia political power is in the hands of big capital. Consequently, everything that is unsuitable for big capital can be removed in à “legal” way. The exports of the outer territories, i.e., Sumatra, Borneo, Celebes, etc. were smaller than that of Java. This applies to the exports of the produce of the big plantations. The exports of the produce of the peasant plantations are still very considerable on this island. In 1927 import duties on imports in the outer territories amounted to 26,490,759 guldens, and export duties to 12,779,434 guldens. Thus, in that year import duties in the outer territories were only twice as much as the export duties, whereas in Java import duties amounted to 28 times as much as export duties. This shows the enormous burden that is borne by the peasants in the so-called outer-territories.

As is the case in Java, it will be impossible under these conditions for a strong native peasantry to arise in the outer territories. The policy of the “Open Door” will have the same effect on these islands as it did in Java, namely, the oppression of the overwhelming majority of the peasantry and their transformation into proletarians (coolies) which are so necessary for the development of big capitalist plantations.

The export duty on the produce of the native producers is all the more brutal for the reason that no such duties are imposed on the exports of the produce of the big plantations with the result that the latter can far more successfully compete on the foreign markets with the native producers.

The development of Indonesia is proceeding very rapidly, and the peasantry know from the impoverishment that goes on in Java whither capitalist development is leading. Hence, the discontent of the peasantry with the Dutch Government and its sympathy for the Communist Party; for they know that the Communist Party is the only Party that takes up a consistent struggle against the government. In Java the process of class differentiation has gone the farthest. But this does not mean that the other Indonesian islands are of less significance; the peasant movement in the outer territories is of extreme importance for the movement in Java. In order to weaken the power of Dutch imperialism, we must mobilise the peasants against foreign domination in the outer territories, i.e., in Borneo, Celebes and the other islands also.

In Java there are large modern enterprises owned by a few banks, and for that reason the Communist ideas can be far better understood in Java than in those districts were no such large enterprises exist. In Java we not only have large agricultural enterprises, but also other branches of industry, such as the oil industry, printing, modern docks, metal works, railways, etc., which employ wage workers. The class enemy stands out in a much more palpable farm in Java than in the other islands.

Many comrades are not well informed about the Communist movement in Indonesia, and moreover, Indonesia does not play the same role in world politics as is played by China and India, so that it does not attract so much attention as these countries do. The role that Indonesia can play is that of a meaty bone for which the dogs of imperialism will struggle.

The Communist Party is young. It was formed in 1915 under the name of the Indian Social Democratic League by Dutch Social Democrats of the Right and Left wings, for the purpose of studying the political and economic problems of Indonesia. It was not the intention then to carry on agitation among the broad masses of the Indonesian population, but merely to carry on propaganda for Socialist ideas. The existence of a proletariat in Indonesia that could serve as a vehicle for the Socialist ideas, as was the case in Europe, was denied. Subsequently, this Socialist study circle grew up into a mass Party. The outbreak of the war suddenly caused a rise in the cost of living of 400%. In the cities strikes for increases of wages broke out. The industrial boom that prevailed in Indonesia at the time enabled the workers to win these strikes, with the result that the strike became a popular method of struggle. These strikes were led by our comrades, and so they came to the forefront when the class struggle, broke out in Indonesia for the first time.

The native comrades, at that time, worked in the Sarekat-Islam, which was very strong then. This League was founded in 1913 by native small shopkeepers and originally pursued the aim of combating Chinese competition. In its further development the Sarekat-Islam became transformed into a political organisation and during its most prosperous period had a membership of two millions.

The growing influence of our comrades in the Sarekat-Islam and the spread of Socialist ideas among its members led to the expulsion of the Communists in 1923. It should be mentioned here that the Indian Social Democratic League in 1920 was reorganised into the Communist Party. The expulsion of the Communists resulted in a considerable weakening of the Sarekat-Islam, for the majority of the members went with us. On the initiative of our Party, the Sarekat-Rajat Peoples League was founded in the same year, which was opened for membership of all Indonesians irrespective of nationality or religion. The defeat suffered by the Sarekat Islam in 1923 must be attributed to the acute economic crisis that prevailed from 1921 up to about 1925. This crisis resulted in the ruin of numerous independent petty bourgeois. In the same period the government carried out a very stern taxation policy for the purpose of preventing the hoarding of gold which also resulted in the ruin of a large number of the petty bourgeoisie. Not only were these petty bourgeois discontented, but so also were the workers and employees in government and private offices and the intellectuals, who, as a result of the economies introduced by the government, lost their jobs. The discontent of the masses found its outlet in May 1923 in the general raliwaymen’s strike and the attempted assassination of the Governor-General. This general strike was the first important mass attack of the workers against imperialism. The general strike was suppressed, an Anti-Strike law was passed and freedom of assembly was annulled.

This railway strike was the first experience of the masses proving the correctness of the Communist view that the State was nothing more than an instrument of coercion in the hands of the capitalists, and in Indonesia in the hands of the imperialists. The strike, therefore, had a revolutionising effect upon the further development of the popular movement in Indonesia.

The Government shut down our schools because the teachers whom we elected were Communists. Further proof of the hostility of a capitalist government towards the masses of the people was given in the persecution of the Communists and the suppression of the strikes in 1925 and the beginning of 1926. These proofs of the accuracy of the Communist views. greatly increased the authority of our Party among the masses. In 1923 not only was the Sarekat-Islam eclipsed by our Party, but so also was the National Indian Party which up to that time was to some extent the vehicle of national revolutionary ideas. Owing to its considerable loss of membership, this Party was dissolved in 1923 and the revolutionary elements either joined our Party or the Sarekat-Rajat which was influenced by our Party.

The decline of the Sarekat-Islam and the dissolution of the National Indian Party, in my opinion, marked the conclusion of the period of the petty-bourgeois leadership of the national movement. The victory of the Communist Party signified that from 1923 onwards, the proletariat took the hegemony of the Indian revolutionary national movement and that from this time onwards it became the mission of the proletariat to lead the liberation movement of Indonesia to victory.

In 1923 the leadership of our Party passed into the hands of the native comrades because the Dutch comrades were deported one after another by the Government. The Government believed that by deporting the Dutch comrades, the Communist Movement would automatically disappear. But it had the very contrary effect. The very fact that the leadership of the Party was in the hands of native comrades still further raised the prestige of the Party in the eyes of the masses, for we must not forget that in a colonial country like Indonesia, the masses are somewhat prejudiced against the Dutch comrades.

In June 1924 the first Congress of the Party, since the capture of the leadership of the national movement, was held. At this Congress the slogan was advanced: enough of agitation; organise and strengthen Party discipline. This slogan was called forth by the fact that as a result of our increased agitation, the masses streamed into the Party in large numbers, and it was necessary to consolidate these masses organisationally.

After this Congress our Party grew very rapidly. New trade unions were formed and the existing unions were strengthened. Our numbers increased so rapidly that six months later, in December 1924, a special conference was called in order to discuss the situation and to take the necessary measures. At this conference we discussed the possibility of capturing power. At the same time the Central Committee made a proposal which bore a distinctly ultra-Left character. This proposal was to the effect that the Sarekat-Rajat, which was affiliated as a body to our Party, be dissolved on the ground that it was a petty-bourgeois organisation and that our members could not carry on a consistent Communist line of tactics in that organisation. This proposal, however, was defeated by the overwhelming majority of the Conference on the ground that the petty bourgeoisie in Indonesia was a revolutionary force with which our Party must co-operate.

The unrestrained growth of our Party eventually compelled the government to take action against us. The Communist Party had the leadership of the most important trade unions, likely the Railwaymen’s Union, the Dock and Transport Workers’ Union, the Post, Telegraph and Telephone Employees’ Union, Printers Union, the Metal Workers’ Union and the Plantation Workers’ Union. Every strike that broke out was regarded by the police as a Communist strike and as such suppressed. The strike leaders were arrested and imprisoned. The measures taken by the Government against the strikers served only to stimulate the hatred against foreign domination still more.

In January 1925 the government tried to introduce a sort of Fascist regime by hiring criminals to intimidate the members of our Party and to remove the leaders. But this led absolutely to nothing. Our comrades organised defence corps and within a few weeks this pseudo-Fascism was dissolved.

After this setback the government was compelled to come out openly itself as the suppressor. The measures taken against our Party became more and more brutal. Again freedom of assembly was annulled and our Party was compelled to carry on propaganda illegally.

The intensified terror finally led to an armed uprising against the Government. We believed that it would be better to die fighting than to die without fighting. The uprising in Java spread to other parts, but in the meantime our leading comrades in Java were arrested and many of our members were discovered by the soldiers and the police and killed.

The rising broke out in Java on November 13th, 1926. The plan was to organise a general railway strike which was to serve as the signal for an uprising in Java and Sumatra. This plan was not carried out, however, because all the capable and experienced comrades were arrested. The rising in West Java lasted for about 3 weeks. In other parts of Java, however, no big movements took place. Only here and there’ conflicts took place with the police and acts of sabotage were committed.

The Government was completely taken by surprise, and ‘feared that the rising would spread over the whole of Indonesia. This is shown by the fact that only 600 soldiers were sent to West Java to suppress the rising there, and that is why it lasted so long there. In the capital, Batavia, the rebels tried to storm the prison, but were driven back. For several hours they occupied the Central Telephone Station. In Batavia the rising did not last for more than one week.

The rising in West Sumatra broke out two months later, in the beginning of January. It lasted four weeks, and was finally suppressed by the military.

The constant changes in the leadership of the Party due to the arrest and banishment of our leading comrades, resulted in many mistakes being committed by the leadership. One of these mistakes was that the rising in West Sumatra broke out two months after it broke out in West Java, which enabled the government easily to suppress it. Before the uprising all the native population were friendly or at all events not hostile to our Party. During the uprising in West Java in some places the members of the Sarekat-Islam, which was hostile to us, prayed for the victory of the uprising. The overwhelming majority of the Chinese population, and their newspapers which in Indonesia exercise considerable influence, adopted an attitude, if not friendly, then. at all events not hostile, towards our Party, before, during and even after the uprising.

Another serious mistake we made was that we failed to draw the masses of the workers into the struggle. The masses of the workers in the cities, as well as on the plantations, adopted an attitude of indifference towards the rebel movement.

The local character and the weakness of the uprising at the outset made no impression upon the native police and soldiers, and therefore they were not inspired by it. Only a huge insurrectionary movement in which the great masses take part will make the soldiers and the police unreliable for the governing class. It has been stated here that the army and police consist largely of State employees and that 97% of them were natives. In Indonesia as a whole there are 32,000 soldiers and 28,000 police.

Still another mistake made was that inadequate organisational and political preparations were made for the uprising. The slogans were not sufficiently clear to enable the masses to understand them.

Our Party had only very loose contacts with the Comintern and with our brother Parties. We were very badly informed about the movement in other countries. The few books we had on Communism were confiscated by the police. We had not the opportunity to obtain sufficient theoretical knowledge. Our Party to a large extent developed independently, and under these circumstances mistakes were inevitable. On the eve of the outbreak of the rebellion our Party had a membership of 9000, while the Sarekat-Rajat had a membership of 100,000. Our Party could have many more members, had we not made the conditions of entry more stringent. Only those who thoroughly understood the principles of Communism were eligible for membership, and before he was made a full member he had to pass through a period of probation.

The Party programme adopted at the Party Congress in 1924 revealed extreme ultra-Left tendencies. It contained the demand for the immediate establishment of a Soviet Republic in Indonesia. In my opinion, the demand for nationalisation in itself is a correct one. In Indonesia we have 2100 large plantations owned by a few banks. In addition we have modern railways, coal and gold mines, oil enterprises, and other modern undertakings.

After the Communist Party had won a leading position we were confronted by the difficulty that, bearing in mind the isolated geographical position of Indonesia, it was tactically foolish to put forward demands like that. Indonesia is surrounded by imperialist colonies and a successful Communist movement would be suppressed by the international imperialists who have invested their capital in Indonesia.

Let us now examine the prospects of the Communist movement in Indonesia and whether the Communist Party will be in a position again to lead the Indonesian national movement. The Dutch Social-Democrats in Indonesia regarded the leading position occupied by the Communist Party on the outbreak of the rebellion as a passing episode, and that was the attitude also of the nationalists. I personally do not think that our Party’s success over the nationalist parties was a mere accident. I think, on the contrary, that it proves that the period of petty-bourgeois leadership of the liberation movement has now come to an end in Indonesia. The victory of our Party cannot be ascribed to the energy of any particular Party leader or leaders, for in Indonesia there is no other Party that has so constantly changed its leaders as our Party has done. If in spite of this, our Party has won the confidence of the broad masses it can only be due to the fact that it points out the straight road to the struggle against Dutch imperialism and because the programme of our Party, although it reveals certain ultra-Left tendencies, nevertheless clearly and distinctly expresses what we want and how we propose to get it.

It is true, comrades, that the proletariat in Indonesia is not the same kind of proletariat that you have in Europe. It is a proletariat with a peasant ideology. But because this proletariat works on the plantations under the dictatorship of the big capital, this agricultural proletariat can easily appreciate Communist ideas. On the plantations they work collectively and are collectively exploited.

To my mind it is not an accident that the Communist Party alone succeeded in spreading its influence over the whole of Indonesia. No other Party managed to do this.

In April this year, a nationalist writing in the nationalist organ “Ssoloch Indonesia Moeda” tried to contrast nationalism to Communism. Like the reformists, he regarded the Communist movement as an intrusion in the national movement. The Communist movement was merely an intermezzo according to this writer. He wrote:

“Communism during the past few years is the cause of the setback of nationalism in our country. It has not only penetrated the cities and the villages, but also the workshops and the factories. In accordance with their principles, the Communists made their base in the trade union movement, which compelled Dr. Fock (the Governor-General) to introduce Par. 161 (the Anti-Strike Law). The severity of the laws, however, achieved the very opposite to what was intended.

At the same time we saw that as Communism grew in influence in the cities and villages, in the workshops and in the factories, nationalism was compelled to remain quiet and refrain from carrying on nationalist propaganda. Everywhere Communism was discussed and even at the risk of losing popularity nationalism had to be content with the role of onlooker. It dared not undertake any activity…”

What does this statement imply? It implies nothing more nor less than that the nationalists were incapable of leading the masses and had to leave this leadership to our Party. It proves that the nationalists in Indonesia are incapable of leading the struggle for liberation to its victorious end.

After the rebellion was suppressed, the nationalist organisations, partly because of the government indulgence towards them, and partly because of the fact that our leading comrades were either in prison or in banishment, began to revive. The Sarekat-Islam has once again achieved a certain amount of influence, and the Party “National Indonesia”, which was formed in 1927 has won a certain amount of popularity. It is usually the case that reaction sets in among the masses after a defeat, and that they come under bourgeois or petty-bourgeois influence. But it must be expected that as soon as the masses have recovered from their defeat and again enter into the arena of battle, they will throw off the leaders of the nationalist organisations in the same way as they did in 1923.

In Indonesia the Governing class, that is Dutch imperialism, is weak because it exercises little or no ideological influence upon the broad masses. The masses are illiterate and therefore the Government cannot influence them intellectually. The hatred of the broad masses towards the Government is not only a class hatred; this hatred becomes more intensified by the policy of the “Open Door” by which they hope to another religion. All these circumstances taken together make the domination of imperialism in Indonesia very unstable. The Dutch imperialists try to secure their possession of Indonesia by the policy of the “Open Door” by which they hope to obtain the support of the other imperialists. The development of this policy, however, leads to the growth of the “internal enemy” the proletariat.

Our primary task now is to restore our broken Party apparatus. We must restore also the trade unions, because without the trade unions the Party can never play a leading role. This is all the more important for the reason that, in our opinion, the nationalist parties will be incapable of leading the masses when the latter once again take up the offensive. This work is important also from another point of view. We must prevent the traditions of the other parties becoming deep-rooted among the masses. We must do all in our power to foster the well-deserved traditions of the Communist Party among the masses and to develop them in order that the Party may set the masses into action at the decisive moment.

These are very difficult tasks, comrades, because owing to the geographical isolation of Indonesia, we can only with difficulty maintain contacts with our other brother Parties. We must, however establish permanent contacts with our brother Parties in order to be able to make use of their experiences and in order to avoid making mistake after mistake for which we have to pay very dearly.

As I have already said, we lack well-trained active members. We must do all in our power to give our members a good Marxian-Leninist training. Lenin said that a revolutionary movement without a revolutionary theory is impossible. The agricultural industry is the principal industry in Indonesia. This facilitates the development of anarchistic tendencies. The poor city petty-bourgeoisie are also inclined towards anarchism. There was a time when the propaganda of our theories was mocked at. We were told it is not theories, but deeds that change the world. On the basis of these ideas, bomb-throwing and other acts of individual terror were engaged in, as was the case in Russia at the end of the last century. A Communist Party with a theoretically trained leadership will be able to overcome this anarchistic ideology.

The Communists must now work in the various nationalist organisations. They must compel the leaders of these organisations to carry out a revolutionary policy or else expose them.

Particularly important is it to carry on work among the peasantry. The peasants must be organised in peasant leagues or peasant committees in order to prevent the imperialists from utilising them. The struggles in West Java and Western Sumatra showed that the peasants are ready to join a struggle against the foreign domination.

The Government is continually striving to create confusion in the national movement by promising political reforms which, however, the masses cannot understand and which will certainly not improve their economic conditions.

In our draft theses we have put in the following slogans as a means for rallying the masses: Right of combination; freedom of assembly and free press; general amnesty for political prisoners; abolition of death penalty; improvement of the conditions of life of the broad masses. These demands of course are to be achieved through the principal demand: Indonesia free from Holland.

Comrades, our Party has made many serious mistakes. I hope, however, that through our closer contact with our brother Parties, we shall obtain their advice and the benefit of their fighting experience. We have not the slightest doubt that with the support of the Comintern and of our brother Parties our Indonesian Section will fulfil its revolutionary duties.

Thirty-third Session. Moscow, 16th August, 1928 (Afternoon).

Comrade de VISSER (Holland): Comrades, the Dutch Delegation is pleased to see that in the theses to Comrade Kuusinen’s report there is for the first time a document which deals fully with the problems of the revolution in the colonies and refers to the experiences of the last years. But in these theses as well as in the various reports, no mention is made of a very important part of our colonial policy, namely, the duties and tasks of the proletariat and the Communist Parties in the imperialist countries in regard to the colonies and their liberation struggle.

It is of the utmost importance to make workers in the capitalist countries realise that they must support the revolutionary movement in the colonies because it is in their own interests to see the domination of their own bourgeoisie over the oppressed colonial peoples abolished. It is not enough to assert and point out this in general in our propaganda and agitation. We must be able to demonstrate this concretely and to prove it conclusively in every country in accordance with the historical conditions which prevail there.

I want to draw your attention to the idea expressed by Marx in one of his letters to Engels in 1869 concerning the relation between Great Britain and one of its colonies, namely, Ireland. He says in this letter that apart from all international and human phraseology about “justice for Ireland”, it is in the direct interest of the British working class to get rid of its present connection with Ireland. He even adds that he believes now that the British working class will never be able to do anything before it has got rid of Ireland. Is not the substance of our policy in regard to the colonial questions expressed in this and many similar sayings which we meet in the works of Marx and Engels? Colonial domination ties a section of the proletariat of the oppressor nations to “its” bourgeoisie; hereby it divides this working-class and makes it more difficult for it to take up the offensive against the capitalist class and to proceed to revolution and the construction of Socialism. We must be able to explain this to the European workers. We must also persuade them that in the construction of Socialism in their industrial countries they will stand very much in need of the help and the economic support of the revolutionary masses of the colonial countries. Comrades, it is perfectly clear that the food question in countries such as Great Britain, Germany, etc., will play one of the most important roles in the revolution. Therefore, the relation to the world rural district, to quote our programme, to the populous colonial countries which produce raw material and foodstuffs is of decisive importance.

On the other hand, it is only support by the countries where the proletarian dictatorship is introducing Socialism, which enables the colonial countries to develop after the bourgeois-democratic revolution their productive forces without necessarily going through the capitalist stage.

Thus, the rebellious masses in the colonies and the revolutionary proletariat in, the mother countries are interdependent. These relations which are of enormous importance for our policy, must be fully dealt with in the theses on the colonial question. The same applies also to the tasks which arise therefrom for the Communist Parties in the imperialist countries.

I will deal now with conditions in the Dutch colonies, in Indonesia. There is hardly a colonial country where the bourgeoisie has succeeded to utilise all the resources of the country for its own profit and to impede the independent economic development of the native population to such an extent as in Indonesia and especially in Java. This has been resented by the Javanese people to an ever-increasing extent. In the last century no less than 70 rebellions took place there against Dutch rule.

It is one of the main tasks of our Party to arouse the interest and sympathy of the Dutch working class for this struggle and to lay thereby the foundation for a solid and loyal alliance between the Dutch proletariat and the Indonesian masses. The Communist Party of Holland realises that this is one of the most important spheres of its activity. Even the bourgeois press is compelled to admit that the Communist Party of Holland alone keeps alive the question of the revolution in Indonesia. This was said in connection with the propaganda carried on by our Party at a big colonial exhibition in Arnhem, in parliament, in the press and public meetings.

In this respect we have to struggle first and foremost against the Social-Democrats. Comrade Ercoli has already mentioned that in regard to the colonial question the Dutch Social-Democratic Party has always been the most reactionary and most reformist party. It was for instance a Dutchman, van Kol, who was the first to defend the reformist standpoint in regard to this question at a Congress of the Second International held several years before the World War. At the Brussels Congress, too, the delegation of the Dutch Social Democratic Labour Party took up the most reactionary standpoint and positively refused to recognise Indonesia’s right to independence. The attitude of the Social Democrats during the insurrection in Indonesia in 1926 when its spokesman, Stokfish, advised that the death penalty “should be applied only very cautiously”, is well-known.

There is another point which deserves special mention, namely, the economic policy not only of the bourgeoisie, but also of Social Democrats in regard to Indonesia. All bourgeois opposition parties advocate of course various small reforms which keep strictly within the limits of colonial exploitation. Generally speaking, they set their hopes on the birth of capitalist elements within the Indonesian population itself in whom the Dutch bourgeoisie and also the Social-Democrats see a prop and pillar for their regime of economic and political oppression and exploitation.

In Europe Holland is probably the country with the most highly developed labour aristocracy. In accordance with this is the entire policy of the Dutch Social Democrats which is based on the temporary interests of the upper stratum of the proletariat and the corrupt trade union and Party bureaucrats. Against such an array of forces the struggle of our Party is by no means easy, and it is of course made still more difficult owing to the criminal split attempts of politicians such as Wynkoop, the renegade who by his efforts to divide the revolutionary workers of Holland, is greatly impeding the struggle for the independence of Indonesia.

Against all Social-Democratic attempts to avoid clarity in regard to this question, we are setting our slogan “Indonesia free from Holland now”. We must struggle against the attempts of the Dutch bourgeoisie and Social-Democracy to deceive the Indonesian masses with pseudo-reforms of the type of a peoples’ council and such-like measures. The mass of the Indonesian population, the oppressed and exploited small peasantry and the enslaved proletariat can lessen their burdens and pave the way for further development only through the bourgeois-democratic revolution and through the dictatorship of the workers and peasants. The Dutch proletariat cannot achieve the Socialist Revolution unless it allies itself with the Indonesian masses. Just as work for the liberation of Indonesia is one of our most important tasks, contact with the Dutch workers and propaganda among them for the cause of Indonesia is a very important part of the work of our Indonesian brother Party.

To create and strengthen the alliance between the enslaved masses of Indonesia and the revolutionary workers of Holland, such is the most important task of our two Parties, as a component part of the great strategical plan of the Communist International, the grand idea of Lenin!

Thirty-fourth Session. Moscow, 17th August 1928 (Morning).

Comrade MAUAWAR (Indonesia): Comrades, the Communist insurrection in Indonesia at the end of 1926 and in the beginning of 1927 did not come like a flash of lightning in a clear sky, but it was well-prepared. It can be said that the general strike of the metal workers of Surabaya in December 1925 was the commencement of the insurrection.

At the end of 1925 the Communist Party of Indonesia had reached its height of development and its influence was very predominant among the working class and peasantry. On the other hand, the terror and the black reaction practised by the Dutch imperialists had also reached its culminating point. The Dutch Government knew very well that at that time the Communist influence among the masses could be exterminated only by means of force. Day after day the provocations of the imperialists were becoming more brutal, and at last the prohibition to hold meetings was proclaimed. Every organisation got its own prohibition notice. The Communist Party of Indonesia received it first and afterwards, the Sarekat Rayat, a revolutionary nationalist party which was directly under the leadership of the Communists. Further, all Red workers’ organisations were doomed to illegality. Up to the end of September 1925, all political and workers’ organisations with Communist leaders were closed down.

It was decided to hold the Youth conference in Solo in the middle of October. Not only all delegations of the youth were present, but also the members of the Central Committee of the C.P.I. and those of the Red Trade Unions.

The whole police force of the province Solo was mobilised, but nevertheless the leaders of the C.P. and of the various Red Trade Unions succeeded in reaching the temple of Prambanan, where a secret conference was held, known as the Prambanan Conference. This gathering was participated in by all members of the Central Committee of the C.P.I. and leaders of the railway workers, seamen and dockers, metal workers, postal workers and other revolutionary organisations. It was decided to prepare a general attack upon the Dutch imperialists and the railway workers should start the action by proclaiming a general strike. This strike would be considered as the signal for the commencement of the insurrection.

Comrades, due to the fact that the leaders were young and lacking the necessary theory and guidance from abroad, we knew very little of the international political situation, and which slogan should be put forward. We did not know how to set up a clear national programme which would attract all classes of the population to join in the insurrection. Therefore it was decided to postpone the campaign to July 1926 in order to give the delegation sufficient time to go to Moscow and to make all necessary preparations.

Meanwhile the reaction was growing all the more sinister, especially at Surabaya, the capital of Eastern Java and the centre of commerce and industry. All workers were ready to go on strike. The metal workers had already submitted 22 demands to their bosses demanding an answer within a week. With many difficulties the strike was delayed because the Prambanan conference had decided that we had to wait until July next year. But the capitalists considered the delay of the strike as a weakness of the workers, and they became more brutal and more provocative.

On December 13th, the strike of the workers of the metallurgical concern, the “Industry”, broke out. The next day, December 14, all important metallurgical concerns came to a standstill. A week later the dockers declared their solidarity with the metal workers and they transmitted 19 demands to their employers.

Comrades, it sounds incredible, but it is nevertheless true that the whole police power of Surabaya was standing behind the strikers. The passive resistance of the Intelligence Department showed that the strike was growing rapidly. Not only the police, but also the government officials were distrusted by the government. The whole police force, from the lowest policeman up to the highest Dutch police officers, were replaced by police from Batavia. The resident of Surabaya protested against this action of the Government stating that the strike had an economic basis. The Resident was discharged from his high post. Meanwhile the suppression of the strike began, premises of the workers’ organisations and houses of Communists were raided. A mass arrest was carried out and the strikers were driven back to work at the point of bayonets. Comrades, the strike of the metal workers of Surabaya was undoubtedly one of the most peculiar and important strikes in Indonesia.

After the Surabaya strike all Communist activities could only be conducted illegally. Persecution and arrests took place in the most barbaric manner.

At the beginning of 1926 many leaders of the C.P. and leaders of workers’ organisations who could escape from the clutches of Dutch spies fled abroad and there a second conference was held. A delegation went to Moscow and the other leaders went back to Java to go on with the preparations. In the meantime, a third conference took place in which also participated several leaders from Java and Sumatra, and the chairman of the C.C., C.P.I. The conference decided that preparations be stopped and the general attack delayed. Comrades, it is clear that this last Conference was causing a split among the leadership of the uprising. While persecution was still terribly raging the split aggravated the unrest of the workers and peasants who were anxiously awaiting the beginning of the insurrection.

The Conference was disastrous and when the uprising in Batavia on November 13, 1926, started it was chiefly carried out by workers, but without declaring a strike because the trade union leaders were bound by the last conference decision. At the outbreak of the uprising all experienced leaders were either arrested or banished. Connections between various sections were totally broken by the authorities. Therefore, a month later after the Batavia uprising, the insurrection of the peasantry broke out at Bantum, and several weeks later at Sumatra. This carrying out of the general attack in different stages was caused chiefly by the lack of communication on the

one hand and by the split on the other. This gave the Dutch imperialists the possibility to suppress the insurgents one by one very easily.

Comrades, the influence of the C.P. of Indonesia before the uprising was very great, not only among the working class and the peasantry, but also among the government officials, the police and the army. This was also confirmed by the so-called Bantam report which speaks of the Communist insurrection in Bantam (Western Java) In the report it is admitted that in many places the C.P.I. had more authority among the population than the government. The insurrection would have had more effect throughout Indonesia if there would not have been the split among the leadership.

Before the insurrection in 1926 when the Communists had the hegemony over the peasantry and the working class, the influence of the Social Democracy extended merely to the well-paid Dutch workers, most of whom are employed in government service and never enjoyed the sympathy of the colonial proletariat. It is known to everybody that these Socialists are willing servants of the capitalists, also in Indonesia.

In 1925 when the Government introduced the regime of economy a mass dismissal of the workers took place and also a great number of Dutch employees were discharged; Van Brakel, the leader of the European postal workers, stated that it is the duty of every loyal worker to support the measures of the government, the aim of which is to overcome the financial crisis and therefore, the Union of Postal Officials could do nothing against the regime of economy.

Van Brackel also requested the authorities to proclaim the meeting prohibition law against the Native Postal Union, of which I was the leader.

During the uprising when the Social Democrats realised that the workers would not be victorious Stokvis stated in a public meeting that it was the serious task of every worker to back the government by breaking the Communist influence among the workers, because the Communists were intending to overthrow the authorities and to disturb the peace of society.

Shortly after the uprising proposals were made from many reactionary quarters to purge the government’s apparatus from all officials who had socialist tendencies. Not only the Communists, but also the Social Democrats were marked as those who were considered as being dangerous. Real consternation reigned among the Social Democrats, because most of them were working as government officials. In order to prevent their dismissal the Executive of the Social Democratic Party made an application to the government, in which they say that the exclusion of Social Democrats from the Government apparatus is based on a wrong idea as to the conception of Social Democracy, etc., etc.

In December 1927, the People’s Council discussed the abolishment of the Exorbitant Rechten (The special rights given to the Governor-General to banish everyone who is suspected of being a dangerous element).

On the basis of this Exorbitant Rechten after the uprising there were more than 2000 revolutionary workers exiled to the malaria smitten district of Boven Digul amidst the jungle in New Guineau. Middendorp, a leader of the Indonesian Social Democracy and a member of the Volksraad declared earnestly that for the time being the Exorbitante Rechten were very necessary. This was not only because he wished to deceive more easily the workers, but also because he knew there was in Indonesia still a great number of revolutionary workers although living in illegality.

A certain Noteboom, the leader of the “Spoorband” (Railway workers’ Union) and a member of the Social Democracy has lately been trying in every way to gain influence among the native railroad workers. During 1927 he succeeded in attracting a group of railway workers at Bandung to the native railwaymen’s union newly formed by him. On October 25, 1927, the members of the C.C. of this Union assured the Chief Inspector of the government railway company that their union would engage only in economic questions and that it had nothing whatever to do with the political movement. Chief Inspector Stargaard expressed himself fully satisfied and he hoped that the new union of the native railroad workers would in future be able to work in contact with the authorities.

In the last time, when the Nationalists were getting more and more sympathy among the workers and peasants, the

Social Democrats were also busy arranging meetings in which they express their sympathy with the national liberation movement and speak of the possibility of co-operation between Social Democracy and the Indonesian nationalists. Stokvis, in a public meeting on March 1928, stated that the present policy of the Government, i.e. the suppression of the Communists, is correct. The Indonesian workers must not be influenced by destructive doctrines, but they must be told to live in peace with the employers.

The suppression of the Communist Party gave a broad scope for revival to the national movement in the middle of 1927. Directly after the uprising the National Party of Indonesia was established by Indonesian intellectuals. The new party is pursuing the policy of rejecting any co-operation with the Dutch Government granted a kind of concession to the is the boycott of councils created by the government, like the Municipal Councils, the Provincial Councils and the People’s Councils.

In order to win over the sympathy of the nationalists and to hamper the revolutionary development of the nationalists, the Dutch Government granted a kind of concession to the nationalists, i.e. to increase the number of the native members of the Volksraad, so that the natives would form the majority in that council.

In the so-called Indonesian Council, the advisory body of the Governor General, there would also be appointed a native member. In spite of this concession the revolutionary nationalists still reject the participation in the said Councils.

Notwithstanding the fact that this national movement exists already for nearly two years, and in spite of its clear programme which demands the complete liberation of Indonesia from Holland’s domination, this National Party is not yet enjoying the sympathy of the masses. This is due to the fact that the leaders are not able to fulfil the will of the masses, in their economic demands. Apart from this the influence of the Communist Party up to now is still predominant among the masses.

Thirty-sixth Session. Moscow, 18th August 1928 (Morning).

PADI (Indonesia): On behalf of our Delegation, I wish to make some few remarks on three points in the theses of Comrade Kuusinen: In Par. 5, Page 5, we read:

“Colonial exploitation however, which is carried on by the same British, French and other bourgeoisies, far sooner retards the development of the forces of production in the respective countries.”

On Page 14, Paragraph 15, we read:

“This poverty of the peasants means simultaneously a crisis in the industrial home market, and on its part constitutes a severe limitation on the capitalist development of the country.”

In our opinion on the contrary, the poverty of the peasants and the declining purchasing power of the colonial proletariat hastens the capitalist development of the country. The poor peasants and the workers, on account of growing unemployment and cutting down of wages, cannot buy foreign goods. In order to enable the colonial proletariat to buy cheap goods the exploiting bourgeoisie is compelled to industrialise the colonies in

order to sell goods at cheaper prices. The chance of industrialisation of the colonies is not slight, because the raw materials are very easy to get and at cheap price and the wages of workers in the colonial countries are far lower than those of the capitalist countries.

We read further in Paragraph 6, Page 6.:

“A real industrialisation of the country, especially the building up of an efficient machine industry, which make for the independent development of the productive forces of the country are not fostered by imperialist monopoly, but are retarded.”

Our opinion is that since the stabilisation of Europe a beginning is made to foster industrialisation in certain industries. We cannot say with certainty how big the amount of foreign new capital already transferred to the colonies since the stabilisation is, but it is certain that the transfer of enormous amounts of new capital in the different enterprises is going on. We believe that our comrades know very well that foreign capital, viz., accumulation of surplus value which is being transferred to the colonial countries gives more profit when it is put in sugar, rubber, tobacco and other enterprises than in heavy industries. For example, in Indonesia many enterprises pay 30-60% dividends to their shareholders. This is a proof that capital in plantation is more profitable than in the heavy industries. We know that with the increased influx of capital in the colonies and simultaneously with the development of modern means of transport and of repair workshops for sugar, tea, coffee, tobacco, oil factories, heavy industries will arise inevitably to meet the direct requirements of machines and other articles at cheaper prices than imported from abroad. The chance of industrialisation is thus not a light one, because labour in the colonies is very cheap. We therefore believe that industrialisation of certain colonial countries will develop in the future to a certain extent. We further note in the these of Comrade Kuusinen in Paragraph 12, which reads:

“The most important task here consists in the joining of the forces of the revolutionary movement of the white workers with the class movement of the coloured workers, and the creation of the revolutionary united front with that part of the native national movement which really conducts a revolutionary liberation struggle against imperialism.”

To show the difficulty to carry out this task, we will take as example the relation between the white workers and coloured workers in Indonesia, which we think may also be an example for the Negro workers in America. The white workers (Dutch) in Indonesia who are holding generally the position of overseers, mechanicians, metal workers, form a group of well-paid workers with average wages far higher than the native workers. The white workers are earning not less than 100 to 300 guilders monthly, especially those who are employed in the sugar, rubber and oil industries enjoy enormous bonuses from 1,000 to 3,000 guilders yearly, while native workers (skilled labour) and coolies are getting not more than 20 to 50 guilders monthly without any other privileges. The white workers are generally a reserve cadre of imperialism. The white workers, knowing the higher life in Europe, work very hard in the colonies to earn as much money as they can. The class differentiation between the white and coloured workers in the colonies creates enormous hatred of the latter. This is being purposely promoted by the Dutch imperialists to continue its policy of divide and rule. This is being proved by many murders of white workers in tobacco, rubber, sugar plantations. These victims are used as tools by the exploited foreign bourgeoisie. The murder and attack on the white workers in Indonesia is growing in the last two years. This is not the fault of the coloured workers, but is the result of the policy of the Dutch imperialists who use the white workers as tools of suppression, strike breakers, etc.

Already since the establishment of the Sarekat Islam (The Union of Moslims in the year 1912) the hatred to all what may be called “Christianity” and “white people” was and is prevailing throughout Indonesia. After the outbreak of the November rebellion in Indonesia this feeling is becoming more acute than ever before. The sharp class-differentiation between well-paid white workers and badly-paid coloured workers and the cruel exploitation of the Dutch imperialists are factors creating a mood which in time of colonial revolution will take the form of revenge of the colonial peoples on all what is “white” and this revenge will be more cruel than that which the Russian workers took of the Russian bourgeoisie and Tsarism.

We are giving here the number of white workers organi- sed in special trade unions. On the whole there are in Indonesia 170,000 Europeans of which 40,000 are male adults.

Federation of Public Servants.

In 1925–membership 9617

In 1926-membership 6548

Union of Higher Officials.

In1925–organised members 758

In 1926—organized members 700

European Federation of Employees.

In 1924–members 2388

Group of Non-Affiliated Trade Unions.

In 1925–5,766

In 1926–10,579

Some of these organisations are in the hands of Social Democrats or organised by Liberals. In time of peace they advocate co-operation, but in times of conflict between coloured workers and the bosses, they hire themselves to the bosses as tools. We have little hope of creating a revolutionary united front of white workers and coloured workers as proved by the critical situation in Indonesia. We therefore recommend to the Congress to instruct our parties in Western Europe to carry on propaganda against the coming of white workers to the colonies with the explanation that the position of the white workers is very dangerous and at the same time their coming to the colonies means the strengthening of the exploitation of imperialism.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n74-oct-25-1928-inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n76-oct-30-1928-inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 3: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n78-nov-08-1928-inprecor-op.pdf