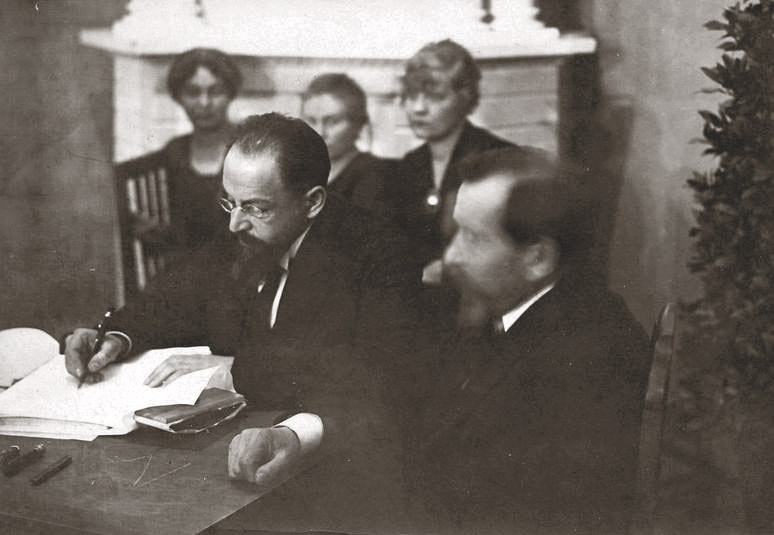

An important addition to the history the 1917 from a central actor written for the Revolution’s second anniversary. This first-person account of the role and activities of the Petrograd Military Revolutionary Committee during the October Revolution and its immediate aftermath from its then chairman, Adolf Joffe.

‘The First Proletarian Government’ by Adolf Joffe from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 6. October, 1919.

IN the smoke and fire of revolutionary events, when the seething activity of the masses is at its height, to give a precise account of the course of events, it is difficult to recollect the separate episodes in their pragmatic consecutiveness.

I remember that when in a gathering of persons, who, from the very beginning, took a leading part in the revolution, the question was raised.as to who invented the titles “People’s Commissary” and the “Council of People’s Commissaries,” it was only after long disputes and exchanges of reminiscences that it was established that the proposal to introduce these titles emanated from L.D. Trotsky.

Not only events themselves, but even separate proposals, decisions, etc., seemed to emanate not from individual persons but from the whole revolutionary mass. They seemed to be the result of the elemental growth of the revolution.

This is especially true with regard to an organisation like the Revolutionary War Committee, which was formed for the defense of the revolution, but very soon became its organising body. When general sabotage reigned in the whole of the old state apparatus, it became the only government, for it combined in itself all the functions of the state. This only lasted for a short time, for the proletarian revolution soon succeeded in breaking the sabotage and set the state apparatus in motion.

There was a moment in the revolution, however, when no apparatus, existed, and when all state affairs were dealt with by the Revolutionary War Committee, which consequently can claim the title of the First Revolutionary Proletarian Government.

The idea of creating the Revolutionary War Council first originated in the days Kornilov. Kornilov’s adventure was mainly direct against the Soviets. The Menshevik-Socialist Revolutionary government of Kerensky was wavering between revolution and counter-revolution; there was even a suspicion that Kerensky himself, who had fallen under the influence of Tzarist generals, who surrounded him, and shamelessly flattered his vanity, was at Kornilova general headquarters. Even the All Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Delegates, which was then entirely dominated by Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, was forced by pressure from below to act in defense of the revolution and directed the Revolutionary War Committee as a fighting semi-military organisation for the defense of the revolution. Immediately afterwards everywhere, in the provinces and at the fronts, similar Revolutionary War Committees were formed.

Owing to the undecided, vacillating policy of the Mensheviks and the Socialist-Revolutionaries, the Bolsheviks began to play a leading role in all these Revolutionary War Committees, although at that time they were everywhere in the minority. This very considerably raised their prestige among the masses. Since the Revolutionary War Committees succeeded in serving the revolution, and Kornilov’s adventure ended in ignominious failure, the Revolutionary War Committees themselves, as a type of a fighting soviet organisation, acquired great popularity.

When the Petrograd Soviet became Bolshevik it became clear that a new revolutionary uprising was coming on with seven-league paces; it became clear that neither the petty bourgeois government of Kerensky nor the Menshevik-Socialist Revolutionary All-Russian Central Executive Committee could tolerate the existence of the menace to themselves in the shape of the revolutionary Petrograd Soviet. It was obvious that they would make use of the first opportunity to dry and destroy it. Therefore, by the resolution of the Executive Committee of the Petrograd Soviet the Revolutionary War Committee was reformed.

This was the spring of the proletarian revolution. The Petrograd proletariat and garrison, almost entirely Bolshevist, full of energy and strength, full of confidence in themselves and their victory, were spoiling for the fight. The Bolshevik orators spoke openly of the new stage of the revolution. At meetings attended by tens of thousands of people, the president of the Petrograd Soviet, L.D. Trotsky, succeeded in bringing workers and soldiers to a state bordering on ecstasy, when all, like one man, swore not to give way a single step in the inevitable and decisive fight. There was no doubt that anybody would break that oath. This was well understood by the representatives of the parties then in power. At one of the conferences of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee Tseretelli, at that time a minister, in a private conversation with the writer, said: “It is obvious now that you will win. But for good or bad, we have held power for six months. If you will hold out even six weeks, I will confess that you were right.” Two years have passed and we are not only “holding out” but are gaining strength every day and acquiring new allies…

The All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Delegates was appointed for October 25th (November 7). A Bolshevik majority was anticipated. The Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries tried to postpone the congress in order to save themselves, but the provincial Soviets refused to obey the order of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and accepted the proposal of the Petrograd Soviet, convening the congress at the date appointed. The delegates came pouring in, and were indeed nearly all Bolsheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries. The situation was coming to a head. The night of the 24th of October was destined to be decisive…

Comrades Lenin and Zinoviev, who, ever since the July days had been forced to conceal themselves, appeared on that night within the walls of Smolny Institute.

In a small room on the first floor an almost permanent session of the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party was held. The latter deputied as its representatives at the Revolutionary War Committee the late Comrade Uritsky and myself, who soon became president of the committee.

The Revolutionary War Committee had its room upstairs on the third floor, if I am not mistaken, in room No. 75. Next to it was the staff, which consisted chiefly of Communists and Left Socialist Revolutionaries, who had to do with military matters; we had no military specialists in those days; but the chief work in that period was carried on not in the Revolutionary War Committee but in the workers’ districts and barracks.

In the evening of the 24th all the telephones at Smolny and of parsons connected with it were cut off. This was a declaration of war.

The Revolutionary War Committee issued an order to immediately occupy the telephone station. This was carried out without bloodshed.

Having started we had to continue. The other necessary government institutions were occupied one by one. No resistance was offered anywhere, only at the Winter Palace, where the Provisional Government was located, the women’s battalion fired at us. Six of the attacking revolutionaries were killed. Not a single woman was hurt. These six heroes were the only victims of the proletarian revolution…

To show the humane and even good-natured treatment of their enemies by the workers and soldiers in the first days of the revolution, I wish to state that when, after a few days, the representatives of the garrison and workers appeared at the Revolutionary War Committee with a request to give a decision with regard to these women battalions, and the writer of these lines asked them what should be done in their opinion, they said. “Dress them as women again and let them go home.” That is precisely what was done with them. Much merriment was caused at the Revolutionary War Committee by the search for such a large quantity of female garments, especially as a part of the women warriors had to be clothed in school girl uniforms which were discovered in the cellars of Smolny, and did not look too martial. What is more, they were too short for many of them.

The impression created by that decisive night was that the Provisional Government was the aggressor and the revolutionaries were only on the defensive. When all the chief government institutions in Petrograd were occupied by the rebels, when not a single regiment of the Petrograd garrison appeared against the revolutionaries–they all went over to our side–we heard news from the neighbourhood: “Cadets are moving from Pavlovsk to Petrograd,” “Such and such regiments advance from Tzarskoe-Selo and Kraanoe-Selo,” etc.

But when these regiments, after meeting the Red battalions, either returned or went over to our side, it became obvious that the revolution was victorious.

We could definitely state that at the Central Committee of the Russian Communist Party, which met again at dawn, one of those who were formerly against the rising–L.B. Kamenev–was first to say: “Well, since the deed is done, let us form a ministry.” Then and there the first Council of People’s Commissaries was appointed.

The congress met in the course of the day; it unanimously sanctioned all that happened and unanimously passed the decrees on “peace” and on “land.” There was a new government, but it was without machinery. All the institutions went on strike. In all the ministries the only persons present were the attendants and lower employees. While the newly elected People’s Commissaries were fighting this sabotage of the government officials and were organising their commissaries, the Revolutionary War Committee had to deal with hundreds and thousands of visitors, which formed a long line from the doors of the corridors and down the stairs.

The whole staff of the Revolutionary War Committee consisted of two or three secretaries and a few typists. Its members, therefore, had to devote twenty-four hours of the day to the questioning of visitors and the decision of all affairs. Everyone appealed to the Revolutionary War Committee. A frightened citizen. appeared with a humble request to obtain a safe conduct, foreigners asked the permission to leave the country, workingmen who took upon themselves the management of factories, came to demand money and various instructions; ladies, students, soldiers, officials–all came with requests and appeals; persons arrested on suspicion of being counter-revolutionaries were brought in. It became necessary to create a special department for such affairs under the direction or Dzerzhinsky–a department which afterwards grew into the Extraordinary Commission to fight counter-revolution. In spite of the strike of all the institutions, Petrograd wanted to eat, Petrograd wanted to live. The Revolutionary War Committee had to give fuel, light, food, etc. The railway trade union, which from the time of Kerensky aspired to have a voice in the composition of the government, attempted to interfere now as well. The committee had a great deal of trouble with this organisation.

This perpetual hurly-burly prevented us from remembering the details of separate episodes in the activity of the Revolutionary War Committee. In some rare cases such episodes created a mild sensation. Such, for instance, was the appearance in the committee of our foremost scholars, members of the Academy of Science, who came to beg for the liberation of the ministers of the Provisional Government on the ground that they were “outside party politics.” Most of the members of the Revolutionary War Committee had spent long years in Tzarist prisons and served sentences at hard labour, and such a request caused a natural query: “Why did the ‘non-political’ scholars not appeal to the Tzarist Government on their behalf?” The release of the arrested minsters was refused, but the request to improve their lot was granted.

The Revolutionary War Committee had to pass some anxious moments at the time when Kerensky and Krasnov were moving on Petrograd. The directions for defense were issued at the front and the committee, which was constantly visited by representatives of regiments and the Red Guards (the Red Army had not yet been formed), was mainly there to settle all sorts of misunderstandings. We received news that munitions were dispatched, but no guns, or vice versa, of that artillery has arrived without cover, or that certain units lost their way and did not know where to proceed. We had to make immediate inquiries and follow them by urgent measures. But our chief task was to obviate the panic which arose here and there. The very fact that comrades were watching day and night at Smolny, that they were quietly, doing their work and were prepared to take the necessary measures, acted as a tonic on the delegates from the front; sonic came in a state of panic and left reassured. I recollect a commander who showed great nervousness, and who was persuaded after a long while that this confusion was quite natural, considering the complete absence of any military apparatus, but that we are bound to win, as we are backed by the masses. He exclaimed in the end: “True, comrades, worse things happened during the French Revolution; whole regiments surrendered to one another.”

Gradually work began to move along a beaten track. The Revolutionary War Committee was being relieved of much of its work, partly by other newly founded institutions, to which it appointed its commissaries, partly owing to the fact that the People’s Commissaries were breaking the back of the strike or forming institutions run by new men. Work was gradually drifting into the People’s Commissariats. The Revolutionary War Committee became useless and was dissolved.

The Revolutionary War Committee was a truly proletarian government. It was only an executive organ of the proletariat, for the whole revolutionary people took part in its work. It forged the weapons for future fights in the flames of the revolution, and realised the constructive will of the proletariat. It is even difficult to indicate what this or that person was doing is those days. The whole revolutionary mass acted like one man. All were fighting and working as one whole: the workers were actuated by a single desire–to win. And for that reason the revolution was victorious.

Petrograd, October 25, 1919.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n06-1919-CI-grn-goog-r2.pdf