Prepared foods, automatic service, and chain stores. The craft unions, always insufficient, were utterly unable to respond to the economic and technological changes capitalism was imposing on the food industry. Gertrude Welsh on the need to organize all food service workers–skilled and ‘unskilled’–into one union.

‘The Futility of Craft Unionism with Particular Reference to the Food Industry’ by Gertrude Welsh from Labor Unity. Vol. 2 No. 7. August, 1928.

“We are living in an age of transition and progress. The catering industry is passing through a period of evolution where more or less unskilled service is required and no gratuities called for.

“In connection with this type of institution, commissary kitchens are established and prepared food is delivered in thermos utensils ready for consumption. This method of operation reduces the number of skilled mechanics required in the preparing and cooking of food to a minimum, lessens the overhead cost, and makes their operation serious competition to service establishments.”

One can scarcely help but agree with Edward Flores, president of the Hotel Restaurant Employees Alliance and Bartenders International, who has written the above paragraphs in a recent article of the union’s official magazine, “The Mixer and Server. ” Here we have a far-sighted labor leader, you might be tempted to say, noting his apparent recognition of the fact of “evolution” in industry, and that one type of production often gives way rapidly to another, due to improved technical methods.

So far so good! But what conclusion does President Flores draw from the increasing elimination of the old-style restaurants, with their bowing waiters and magic “tips” by the new self-service places, cafeterias and automats? Does Flores conclude that, since the formerly strategic waiters are less and less needed to conduct dishes, carve meats and serve wines, therefore, the basis of the union must be shifted from the small, home-service restaurants to the self-service, chain businesses?

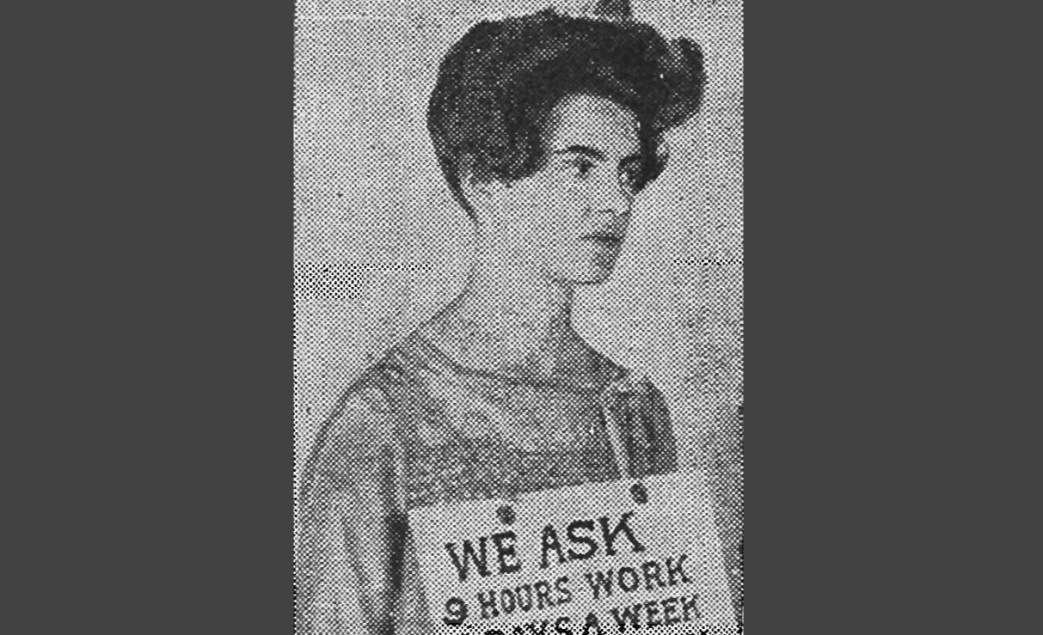

Since the large-scale preparation of food in centrally located kitchens is doing away with highly skilled chefs and bakers, does Flores raise the slogan of “Oranise the miscellaneous kitchen workers”? Since the unskilled labor of women and children, of Oriental and Negro workers, is now being more and more mobilised by the employers, does Flores make special efforts to draw these workers into the unions and to prevent their lowering the hard-won union standard of living? With the sudden reduction of the skilled mechanics and the expansion of the unskilled throughout the food industry, does Flores see the futility of craft unionism and that only widespread, militant, industrial methods can organise the culinary workers?

No, Flores sees nothing of the kind. After all, the vision of a craft union official is as narrow as his means of making a livelihood. If there really were “progress” in the food unions, it would mean that Flores would lose his job, which he happens to hold by virtue of his control over certain waiters’ and bartenders’ locals. Some of these derive their income from boot-leggings, while others survive by bribing the few remaining employers under union agreements to recognise their craft in return for the privilege of greater exploitation of workers in other crafts on the job. Obviously, Flores cannot afford to be interested in all restaurant workers, but only in those who maintain him as a union official. It is logical that he should oppose the Volstead Act, as he does, and it is even more logical that he should oppose cafeterias and automats.

Let’s read further. After paying his respects to our “age of transition and progress,” he goes on to say concerning the evolution from waiter-service to self-service, that:

“In this transformation, service employer and employee have a community interest. We on our part assume the task of bringing the public back to the thought of former methods and environment; while the employer must assume the responsibility of paying his employee a wage worthy of his hire, with hours and conditions of employment which encourage his activity* That brings us down to the question of salesmanship and wastes.” (!)

This paragraph, it seems to me, is a classic expression of one of the forms of modern class-collaboration: in Flores’ words, “community of interest between employer and employee.” That Flores wrote about a “wage worthy of the employee’s hire” with his tongue in his cheek is evidenced by the fact that the emphasis of his article is placed on the need for the workers “not taking advantage of the employer,” while the boss is assured that union workers will give him less wasteful, more efficient service than nonunion; in fact, will be his commission men!

Economics of Class Collaboration

What is important, however, is not so much that American Federation of Labor officials have a class collaboration psychology (this isn’t hard to see); but the economic source from which this psychology springs. Flores wants to keep his job as a waiters 1 president; waiters, too, want to keep their jobs as waiters: that is patent. But underlying this is a “period of evolution,” and a “new method of operation.” It is this economic transformation, which labor “leaders” fight against so fallaciously, that is creating, on the one hand, the psychology of worker-boss cooperation; and on the other, the bankruptcy of craft union.

To take an example from another food trade: the baking industry. The last A.F. of L. Bakery and Confectionery Workers convention met its most vital problem, that of organizing the workers in the trustsified factories, by passing a resolution “to continue efforts to secure from Congress effective action to protect American people from the development of the bread monopoly and to secure for workers in the baking industry the right to organise.”

The official union bakers’ journal commented on this resolution as follows: “If the cracker trust and the bread trust succeed in the intended absorption of the cracker and bread market for their exclusive exploitation, employment of union members becomes a matter of past history in the American trade union movement.”

What a miserable spectacle our craft-union officials make! With Flores, the salvation of the culinary workers lies in uniting with the employers to fight evolution—to put the cafeterias and automats out of business, and to convince the public that it is better to eat in small restaurants than anywhere else (even if only the front half is organised). The bakery union officials are in an even worse plight: they admit that their organisation is helpless until the trusts are busted!

Trustification Continues

Now let us ascertain the facts as to the advancement of mechanisation and trustification in the food industry. The financial statement of a few leading enterprises will serve to indicate the general tendency. For instance, the largest profit gain for 1927 in the culinary business was made by the Silver cafeterias, whose annual profit increased 27.7 per cent, with sales totaling $2,285,338 in six months! In just two cities, Philadelphia and New York, the Horn Hardart automats made sales of over $11,000,000 in the same period.

In the baking industry, take for instance the erstwhile Ward Food Products Corporation, whose recent “dissolution” does not affect the interlocking directorates of this trinity of trusts: the General Baking Co., capitalised at $1,000,000,000; the Continental Baking at $600,000,000, and the Ward Corporation, at $150,000,000. The same stockholders also have controlling interest in the Atlantic and Pacific Tea Co., and in 45 dairy properties, yeast, sugar and machine factories, Pillsbury flour, Carnation milk, etc. Control of the biscuit industry is in the hands of the National Biscuit and Loose-Wiles companies, together capitalised at over $100,000,000!

Government Aids Trust

The conclusion is incontestable that the food industry is more highly trustified than any other industry in the United States. It is a super-trust, with mass-distribution through chain-stores as the latest addition to its gigantic apparatus.

Bankers, drawn in through the necessity for big capital, cement the component trusts together, holding dominating positions on the various boards. Co-operating closely with U.S. government officials, especially since the days of “Bread will win the war,” these bankers are able to use the industry for their own purposes,—for military mobilisation, vote-getting, etc., In return, the government protects the food trust; indeed, helps it to consolidate.

Thus dictatorship is wielded by a few financiers. The fate of small food businesses is definitely sealed. Butchers, bakers, restaurant keepers, grocers: one by one are being driven into bankruptcy or forced to become agents of the super-trust. In 1925, there were 8,279 fewer bakeries than in 1914, despite the 112.8 per cent increase in use of horsepower!

Only Small Shops Unionized

The menace to labor unionism in the failure of these small businesses lies in the fact that only in them have existing unions any foothold. Not a single trust shop has a union agreement with either the culinary or bakery workers’ unions. The number of union bakery workmen today is approximately 26,000 (divided into two internationals); but this number doesn’t even equal the increase of workers since the war, nearly 40,000 factory workers having been added to the 300,000 already in the industry.

In the culinary trades, where almost half a million workers are employed, less than ten per cent are unionised. Of these, 40,000 belong to the A.F. of L. international and their strength is reduced to a minimum by a cross section of craft splits. For instance there are 229 locals altogether. Of these, only 51 take in all crafts, waiters, waitresses, cooks, beverage dispensers and kitchen help. Eighty-four contain just one craft, with 40 of these for beverage-dispensers alone. As a rule, only one craft has a union agreement in most restaurants; the other workers are non-union!

Worse than this, both bakery and restaurant unionists have been psychologized into believing that their welfare is tied up with small business, and that the success of large-scale production means the union’s death-knell. So they allow themselves to be exploited with open-shop conditions under the delusion that they are helping the union by helping the boss! The left wing’s answer to the situation is: Workers, rebuild your unions. Rebuild them from the bottom up on an industrial basis, taking in the entire shop. Organise new unions in unorganized territory on a city-wide, nation-wide scale. Just as the bakery, hotel and restaurant employers are forming giant business unions, so must we form giant workers’ unions!

Our demands to the present union mis-leaders must be: Out of our way! Open the union doors! Reduce the initiation fees! Form joint organization campaigns with all other food-workers’ unions. Combine the two internationals on an industrial basis.

The alternatives of the food-workers are clear: union elimination or industrial organization. Only by industrial strikes, mass picketing, violation of the injunctions, can factory labor be unionized!

In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after its heyday.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labor-unity/v2n07-w26-aug-1928-TUUL-labor-unity.pdf