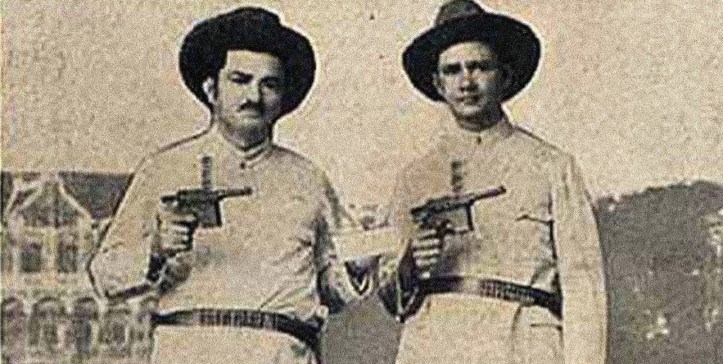

The armed revolt launched against U.S.-backed Venezuelan dictator Juan Vicente Gómez led by the Partido Revolucionario Venezolano, forerunner of the Venezuelan Communist Party, centered on the oil-producing island of Curacao in June, 1929.

‘The Revolt in Curacao’ by Carlos Fleury from Labor Defender. Vol. 4 No. 9. September, 1929.

CURACAO is a small island in the Caribbean Sea. It is part of the British-controlled “Dutch Colonial Empire.” The Royal Dutch Shell operates the largest oil refinery in the world there under the name of “Curacaosche Petroleum Industrie Maatschppij.” This island leaped suddenly into the day’s news, in the middle of June 1929, because of a “coup” organized by Venezuelan and Dominican workers who overpowered the Governor of the Island, the head of the garrison, seized the American ship “Maracaibo” and successfully disembarked in Venezuela, where they began a military movement to crush the criminal dictatorship of Juan Vincente Gomez, puppet of American imperialism. It is reported that these workers, under the leadership of the Venezuelan Revolutionary Party, seized about two thousand rifles, eighteen machine guns, one field gun and sufficient ammunition to carry them through in their enterprise.

To explain this unprecedented coup in modern colonial history, it is necessary to examine the conditions to which the workers of Curacao are subjected.

Before oil was struck in Venezuela, this island had very little importance from a commercial point of view. Its population, amounting then to about 12,000 people, was composed mostly of fishermen and contrabandists who made a living by smuggling goods into Venezuela.

Oil, that precious liquid which has cost already so many workers’ lives brought its doubtful boon to the unimportant and arid island. The Royal Dutch Shell, the owner of the richest concessions in Venezuela, fearing the tyranny of Gomez might be replaced some day by a government less sympathetic to the desires of imperialism, established the “Largest oil refinery in the world” in the small British-controlled Dutch Colony.

New workers were needed to sweat under the tropical sun of Curacao and produce fat dividends for the Royal Dutch Shell. Many men were employed. “Well,” said the managers of the refinery, “if we cannot get sufficient workers here in Curacao, our friend, Juan Vincente Gomez, will provide them for us…”

Many thousands of Venezuelan workers were lured by promises and emigrated to Curacao where they would find a job at a “good salary”: 28 hundredths of a florin per hour or $1.08 per day, for 9 hours of work under a tropical sun, handling crude oil, a most obnoxious mineral.

All the workers were housed in dirty barracks, owned by the company; most of them were fed by the company; their miserable salary went back immediately into the pockets of some officials of the refinery. Due to their housing conditions, to the poor food and to the lack of portable water many workers fell ill and had to be replaced by healthier men. The expanding production of the refinery needed more “hands” also. Two “labor contractors” were dispatched to Venezuela.

The compensation to the “Labor agents” was not sufficient to fill the company’s need for more workers. It was then decided to induce some high official of the tyrannical regime in Venezuela to take a hand and become interested in this “labor agency.”

General Argenis Asuaje president of the State of Falcon was readily found. He was offered a compensation of $1.00 per head sent to slave in Curacao.

The “chief executive” of that state became openly a recruiting agent for the Royal Dutch Shell. This man used the power of his official position to arrest, engage and ship thousands of men to slave in the largest oil refinery in the world. These workers could not go back to Venezuela, they were compelled to remain in Curacao at the mercy of the company. The first $10.00 that they earned was kept by the company as a guarantee for their satisfactory conduct; furthermore if they should “desert” their jobs and return to their native state of Falcon where their families lived, they would be arrested by the police forces of General Asuaje, thrown into jail, compelled to work on the highways in the chain gang, or be recruited into the army. This is the background of the situation in Curacao. Hard labor, miserable salary, terrible housing conditions, the worst food, provocative agents, spies, persecutions from the colonial government and from the government oppression in a center where illiteracy affects 90% of the population. These conditions make it possible to deliver in the cities of the east in the United States oil $1.20 cheaper per barrel than that from the wells of Oklahoma or Texas.

The workers of Curacao know very well all the refinements of imperialist penetration; they know that the governments of Curacao and Venezuela, at a simple insinuation of the Royal Dutch Shell master, enslave, deport, and condemn to hard labor those workers whom they need to enrich the realm of Henry Deterding the “Oil Napoleon”. They know that only a government by them and for them can provide the necessary liberty to enjoy life and the product of their labors.

On January 25th, 1929, Hilario Montenegro, the general secretary of the Curacao Branch of the Venezuelan Revolutionary Party, was murdered upon the command of Juan Vincente Gomez, because comrade Montenegro was a leader in the struggle for the emancipation of the working class. His murderer, Delfin Perez, was taken from jail on June 9th, 1929, at the time of the uprising of the workers in Curacao. To Venezuela he went. He was shot to death after being court martialed by a workers revolutionary tribunal.

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/1929/v04n09-sep-1929-LD.pdf