A report on the history of Serbian Social Democracy for the founding of the Communist International in 1919.

‘Socialism in Serbia’ by Ilya Milkich from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 3. July, 1919.

I. BEFORE THE WAR.

As the revolutionary events taking place in Serbia are attracting much attention it seems appropriate to give a short account of the socialist movement in Serbia.

Socialist ideas have spread among the Serbian people in the second half of the nineteenth century, but, owing to the economic and political conditions of Serbian society, the movement degenerated into petty-bourgeois radicalism. The best-known statesmen and politicians of yesterday and today, such as Pashich, Pretich, Miletich, Predanovich and others in their time called themselves socialists and revolutionaries. Later they became the obedient servants; of Nicholas II., and today they are the agents of the European and American bankers, and the most parked reactionaries and counter-revolutionaries. As to use who remained true to their revolutionary and their socialist ideal, they passed the greater part of the lives in prison, if they did not lose them outright.

Owing to this experience on one side and to the penetration and development of capitalism on the other, the present-day labour movement in Serbia is founded on a solid basis and bears a clearly defined class character.

The first trade-union organisations were founded in Serbia in 1901. But our proletariat could not have its legal political party, the reactionary and absolutist régime of the time forbidding it categorically. In order to break its chains, our labouring class had to resort to illegal struggle. It organized into workers’ societies, philanthropic societies, art schools, choirs; it published its periodicals and booklets legally, under various forms: it held its meetings and sittings at night, secretly, in dark and damp: cellars. In short, it carried on the struggle under extraordinarily difficult circumstances.

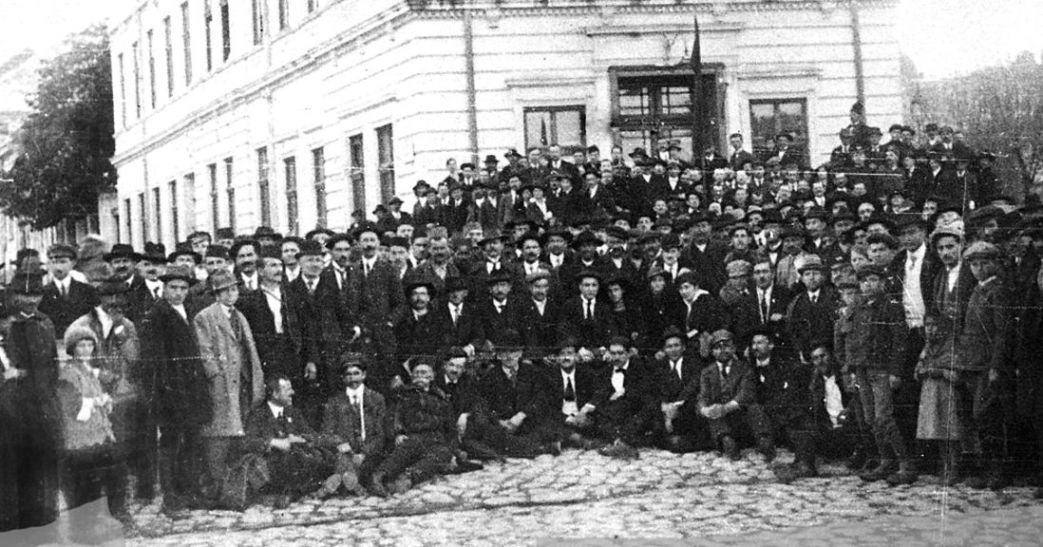

This struggle found expression, on the 25th of March, 1903, in a great revolutionary demonstration. Blood ran in the streets of Belgrade. The Serbian proletariat suffered losses in human lives but the absolutist régime was morally abolished. Two months later, on the 29th of May, 1903, our bourgeoisie and the military clique murdered our last Obrenovich and seized power. The proletariat profited by this opportunity to organize itself politically and economically. Party organisations and syndicates were established in the whole country. On the 20th July, 1903, the first congress of the party and the united syndicates was

summoned in Belgrade. The congress decided to institute the Serbian Social Democrat Party and the General Confederation of Labour.

On a platform of class war, rejecting all compromise and cooperation with the bourgeois parties, and disregarding their democratic finery, the socialist party and the trade-union organizations always marched side by side in the battle for the interests of the working class This accord goes as far as when the General Confederation of Labour delegated members into the central committee of the party and vice versa. Thanks to the purely class character of our movement, thanks to a perfect unity of action in the economic and political sphere and to the socialist education of our small proletariat, the Serbian working class succeeded, after ten years of struggle, in squeezing important concessions from the bourgeoisie. In 1911 the ruling class was constrained to pass a law, by virtue of which working hours were limited to a maximum of ten hours a day. It must be observed that up to then usual hours were from twelve to fifteen a day, and in many cases even sixteen, eighteen and more. This law guaranteed a weekly rest of thirty-six-hours for workmen without distinction of trade, forbid night work for women as well as for boys under eighteen. A series of similar reforms are further contained in the same bill.

Such reforms in a country where industrial development is in its infancy and where the labouring class had but two deputies in the bourgeois parliament of one hundred and sixty-six members, must be reckoned a great success, seeing that in the countries of advanced industrialism and culture, where labour deputies could be counted by the hundred in the bourgeois parliament, social legislation was far in the rear of barbaric Serbia. This of course was due neither to the merits nor to the far-sightedness of our bourgeoisie, which would not hear of concessions and resisted to the last moment. Between 1903 and 1911 it brought before Parliament several bills destined to throw dust into the eyes of the working class. These drafts were mere caricatures of social legislation. In each case the Serbian proletariat replied by redoubling the energy of its struggle and the force of its attack. It did not follow the bourgeoisie to Parliament. It made the bourgeoisie come out into the street to fight on a ground much more dangerous for it, where the capitalist class felt itself beaten and was forced to make concessions. These concessions confirmed the conviction of our working class, that class war and revolutionary methods were the best and only way leading to the emancipation of the proletariat. In this manner we escaped the dangerous diseases called yellow syndicates and reformist socialist parties; even they appeared, they could not do much harm. For when they attempted to penetrate the labour movement, the proletariat energetically repulsed them. Where, in spite of all, undesirable manifestations occurred, a radical operation was undertaken to save the rest of the organism. Separate individuals and entire groups were driven out of the party and the labour movement.

As a result, the reformists and partisans of coalitions and compromises always returned to where they had been sent from, to their proper place in the ranks of the bourgeoisie. Many were speedily made ministers. But the proletariat lost nothing in these deliverers except bad advisers, their loss was rather beneficial to the working class, than otherwise.

It must be admitted that with this conception, we were nearly always in a state of isolation within the Second International. We were pointed out to other wise and far-seeing parties as sectarians and hot-heads. But we would not turn from our way. Our conception of Marxism and of the struggle for the deliverance of the proletariat left no other attitude possible. It is with this conception that we were overtaken by the Balkan war and then by the general cataclysm, that has destroyed millions of human lives and milliards of public wealth.

II. THE PROLETARIAT AND THE WAR.

When in 1908 the rapacious imperialism of Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country populated by Serbians, our young and ardent bourgeoisie profited by the opportunity to clothe its capitalistic ambitions in national garments. It declared the country and the nation in danger. Everything for the army; everything for armament; everything for national defence!

The Serbian proletariat answered: Down with the war between nations! Long live the international solidarity of the workers!

Unfortunately, the socialist parties of Austria and Hungary did not do their duty at this moment. The voice of the Serbian proletariat was a cry in the wilderness. Nevertheless, we did not cease our activity.

In 1909, at the initiative of our party, the first inter-Balkan socialist conference was called in Belgrade, with the aim of uniting the nations of the Balkans and leading the struggle against imperialistic wars to success, the conference demanded the formation of a Federal Balkan Republic. Besides this we made the attitude of the Austrian and Hungarian comrades the subject of discussion at the International Socialist Congress of Amsterdam in 1910; but our indictment unfortunately failed to turn the many other socialist parties from the wrong course.

Nevertheless, when in 1912 Serbia and the other Balkan countries declared war on Turkey for the purpose of delivering our fellow-countrymen, oppressed by five centuries of Turkish Slavery, our party remained true to its socialist and internationalist ideals. It stood up against the war with all its might and voted against war credits, in spite of the envelope of Liberation in which the rulers wrapped it. It proclaimed and emphasised class struggle and socialist revolution as the only means leading to the liberation of the oppressed classes and consequently, of the oppressed peoples as well. We opposed the projects of division and repeated our project of uniting the Balkans in a Federal Republic. Our assertion, formulated by comrade Lapchovich, that the Balkan bourgeoisie wages this war with the aim of conquering new territories, in other words markets, and not the deliverance of any people, what it would quarrel over the division of the spoils and thrust the peoples into mutual slaughter, was not long in being confirmed by events. After having defeated Turkey, when the oppressed Christian peoples were finally “delivered,” the capitalists set the liberates about each others’ ears. So it happened, that in June, 1913, eight months after the declaration of the war of liberation, the allies of yesterday went to war among themselves. In this war Serbia was attacked. The Bulgarian army attacked the Serbian army in the night, without a formal declaration of war.

Still, in spite of the defensive character of the war, our party once again held up the revolutionary banner of proletarian solidarity. With even more energy than in the two preceding cases, it fought against the fratricidal war. We exposed the imperialist character of the war and demanded the formation of a Federal Balkan Republic.

During and after the conflict we steadily continued our revolutionary and socialist propaganda. Our representations began to win the broad masses of the people. Fearing an extensive growth of the socialist party, the government dared not appoint elections for the parliament, although it had two victorious years to its credit. Thus a year passed in procrastination. At last the government was forced to dismiss the discredited parliament and appoint fresh elections.

This was in June, 1914. The canvassing had hardly began when Austria-Hungary sent Serbia the notorious ultimatum of the 10-23rd July.

When in 1914 Serbia was attacked in form, when this time it was reasonable to talk of a defensive war–if this word could have any meaning for us within the capitalist system–our party declared war against imperialist war. It loudly proclaimed that the Serbian and Austro-Hungrian proletariat had no conflicting interests, and that the bourgeoisie was guilty of the bloodshed. We did not hesitate to maintain, that the Serbian bourgeoisie played the part of agents of the western bankers and to Czarism. We appealed to the solidarity of the international proletariat and to revolutionary activity. But on this occasion again our voice remained practically isolated in the Second International. For German and Austro-Hungarian social-democracy, whose government unloosed the world war, the French, Belgian and English socialists, whose ruling class at the last was just as guilty of the imperialist war was those of the Central Powers, all summoned the proletariat to fight in defence of the common fatherland. Thus we were the only socialist party of the belligerent countries–with the exception of the Russian–that protested against the imperialist war in 1914.

It is superfluous to expand upon the vigour with which we were persecuted by leading circles. In the beginning of the war our organisations were deprived of the possibility of action and our press was systematically suppressed. Nevertheless, during the first fifteen months of the European war we carried on a most energetic struggle against our own and the Allied bourgeoisie. Then in the end of 1915 came the great catastrophe of Serbia and the occupation of the country by German, Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian troops, an occupation lasting three years. The losses suffered by the Serbian people surpass any known to history. They affect the working class, most of all. In spite of all these misfortunes, our party did not turn from its way.

During the three years of occupation it unfortunately could undertake nothing of importance, for the remnant of our proletariat was scattered to the four winds; some in occupied Serbia, some in Bulgaria, Austria-Hungary and Germany as prisoners of war or interned; some under arms on the Saloniki front, others in various Entente or neutral countries as fugitives.

Thus collective action was out of the question for our party. Only isolated individuals could lift up their voice in the name of the Serbian proletariat, and this voice was valid only if it corresponded to the attitude of our party and of the Serbian proletariat. It is thus that the attitudes of our comrades Katzlerovich and Popovich ought to be appreciated. When Comrade Katzlerovich spoke in the name of the Serbian proletariat in Kienthal, he was right in doing so, for his attitude corresponded to that of our proletariat. But when comrades Katzlerovich and Popovich went to Stockholm and deposed their memorandum at the Dutch-Scandinavian Committee, they had no right to speak in the name of our party and our labouring class for the simple reason that neither the one nor the other had ever placed themselves on the point of view of those who they pretended to represent. And when I, well knowing our proletariat, affirmed this first in Switzerland and later here in Russia, some comrades hesitated to believe me. But the confirmation of my words was not long in the coming. As soon as our party found a possibility of speaking collectively, this was done and their words left nothing to wish for.

III. THE SERBIAN PROLETARIAT AND SOCIAL REVOLUTION.

We will now examine whether the Serbian socialist party or rather the Serbian proletariat has changed its views during the three years of occupation and since the union of the Serbian people. This question may without fear of contradiction answered: no.

For if our working class could firmly stand on the ground of international proletarian class war when all other socialist parties, large and small, placed themselves on the ground of national defence and cooperation with the bourgeoisie; when there was neither Zimmerwald nor Kienthal, nor Russian revolution, nor German revolution, nor. Austro-Hungarian revolution; when one could talk of the creation of socialist republics and of the dictatorship of the proletariat as of a distant dream–how then could the Serbian proletariat act otherwise today, when social-patriotism social-opportunism and social-imperialism have suffered complete failure and our ideal, so far distant yesterday, has become a tangible reality?

No it could not and has not changed its attitude. We quote some facts touching this subject: the Serbian socialist party is almost the only party which not only at no time condemned or combatted bolshevism and the Russian proletarian revolution, but is one of the few parties that never made reservations on this subject.

In the beginning of this year, when the united kingdom of Serbians, Croatians, and Slovenes came into being our party was invited to cooperate. It refused. More than that, when one of the members of the Croatian socialist party accepted a seat in the government, the Serbian socialist party censured him and declared that a socialist minister in a bourgeois cabinet was no better than a capitalist minister in the eyes of the party, and that he would be opposed just as any other bourgeois minister.

When the Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian troops, in the end of 1918 began to evacuate Serbian territory, our workmen and peasants began to create their soviets. When the Liberators, that is, the Allied troops arrived, these soviets were mercilessly suppressed. The Serbian and Allied soldiery committed the most atrocious crimes in the struggle against bolshevism. According to information received, all persons suspected of revolutionary and bolshevik sentiments were shot on the spot or delivered into the hands of the notorious komitadjis, for execution.

But by suppressing the soviets and murdering the revolutionaries, neither the Allies nor the Serbian government succeeded in diminishing want, starvation and general discontent. On the contrary all this grew from day to day. Our party did not take part in the Bern conference, the conference of the Yellow International. Its abstention was not a matter of chance, for if the delegates of the Allies could go to the conference, the delegates of the vassal states of the Allies might have equally been permitted to go. But our comrades preferred not to go, desiring thus publicly to manifest their non-solidarity with those who betrayed the cause of the proletariat and of socialism. The reason why they did not go to Bern is clearly shown by the letter despatched in January to the bureau of the first communist congress in the name of our party by comrades Lapchevich and Filippovich. In this letter our comrades declare their solidarity with the heroic Russian proletariat and with the international revolutionary proletariat. They also wrote the following:

“The recent invitation of the social-traitors to send our delegates to Bern was refused by our party for we do not wish to have anything to do with the betrayers of socialism…The Serbian social-democratic party as well as the social-democratic party of Bosnia-Herzegovina place themselves on the communist platform. The best part of the workers of Croatia and Slavonia are convinced as, we are, that the road to socialism leads through the dictatorship of the proletariat and that the form of this dictatorship is expressed in soviet power. Is not this declaration clear and without equivocation? Finally, telegrams arrive daily to show us that our party has not changed its attitude and that on the contrary, it has entered upon the final struggle, the decisive struggle for the liberation of the proletariat and the establishment of communism.”

We quote some of these telegram:

“The meeting of Serbian workers that took place on March 26th in Belgrade enthusiastically greets the dictatorship of the Magyar proletariat and declares itself ready to support its Hungarian brothers with all its force till the complete victory of world revolution. Signed: Filippovich.”

This solidarity showed itself in deeds, for a Stockholm telegram, dated April 2d, says:

“It is reported from Vienna, that the Serbian royal government applied to the Allies for military aid to smother the Hungarian revolution. The labour organisations replied by the proclamation of a general strike in Belgrade and other towns. Some days later, on the 12th of April, a Budapest wireless reports: According to information received from Serbia, proletarian revolution is approaching. The Serbian army occupying Hungary looks with envy on their brothers on the other side of the demarcation line, the Hungarian proletarians. In the region of the old line of demarcation, the Serbians threw down their arms and fraternised with our comrades. Today, at four o’clock in the afternoon, French soldiers, coming from Segedina occupied New-Segedina and the bridge behind the Serbians. In order to smother imminent revolt, the Serbian military authorities arrested on Thursday several comrades carrying communist proclamations. The barracks are turned into prisons and are filled with prisoners.”

Two days later, on the 14th of April a French telegram from Lyons says:

“In consequence of the resignation of several members of the Serbian cabinet Mr. Petich is engaged in the formation of a new ministry. All parties save the social-democratic party are to be represented in the new cabinet.”

Since then we have no further information of what is going on in Serbia and the other Yugoslav countries.

According to the preceding, the Serbian proletariat and its political representative, the socialist party, in the past as in the present, always held high the red banner of international working-class liberation.

I am convinced that in the future our proletariat will fulfill with honour the historic task imposed upon it by present and coming events.

The Russian proletariat and the labouring class of the world may be certain of always finding in the Serbian proletariat loyal and sincere comrades in the establishment of the communist international. The heroes of the Russian revolution, whose superhuman efforts have evoked the admiration, sympathy and solidarity of the workers of the entire world, may be sure that the Serbian peasants and workmen will not be the last to hold out to them a brotherly hand, even if at the present moment circumstances prevent them from being among the first.

Moscow, April 30, 1919.

Ilya Milkich.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n03-jul-1919-CI-grn-goog-r2.pdf