The editor of Southern Worker on the impact of the Great Depression’s beginning on Southern farming and Black share-croppers in the context of struggle for ‘self-determination for the Black Belt.’

‘Some Rural Aspects of the Struggle for the Right of Self-Determination’ by James S. Allen from The Communist. Vol. 10 No. 3. March, 1931.

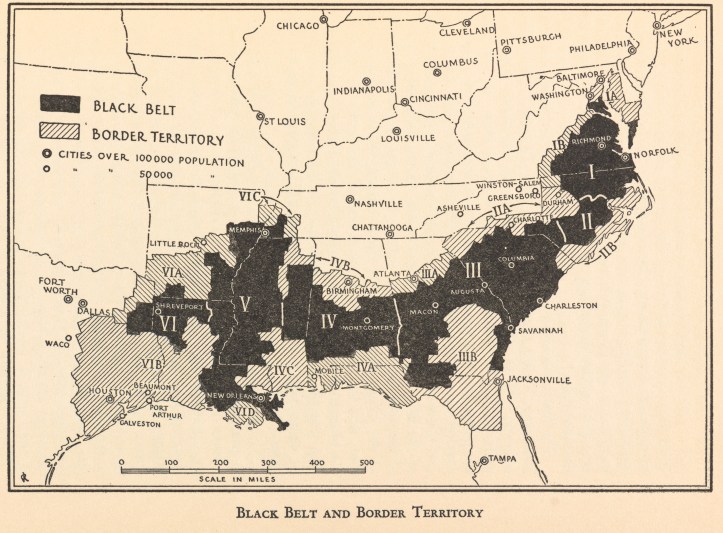

THE national-liberation movement centering in the struggle for the right of self-determination among the Negro masses will necessarily be concentrated in the Black Belt of the South, an area roughly designated as East Virginia and North Carolina, the state of South Carolina, central Georgia and Alabama, the delta regions of Mississippi and Louisiana, and the coastal regions of Texas. In this area there are 264 counties in which the Negroes make up the majority of the population, and two states—Mississippi and South Carolina—in which they form the majority of the whole population.

These regions are also the center of cotton and tobacco production, the money crops of the South. In the old cotton states of South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi alone there is a rural Negro population of 5,000,000. It is in this region also that the chronic farm crisis has had its most constant development and produced its most devastating results, working within the framework of a tenant system, retaining many of the features of feudalism in which have been interwoven the oppression of a caste system.

The stepping stones towards the development of a national-liberation movement for self-determination, with all its highly developed political features, must be provided by a rural program of struggle based upon the crying daily needs of the rural masses in these sections. A struggle based on such demands is of itself directed against the ruling white landlords and their governing apparatus, by the very conditions of the rural situation. No group of Negro farmers can raise such a demand as retaining the full proceeds of their crop, without striking at the very roots of the tenant and credit system. The struggle for the abolition of this system leads into and goes along with that for the attainment of state unity in the Black Belt.

Southern agriculture revolves about the growing of cotton and tobacco, chiefly the former. With the exception of sugar, rice, and insignificant crops of peanuts and soy beans, cotton and tobacco provide the money income of Southern farming. Other crops like corn and truck are mostly consumed on the farms. Cotton or tobacco provides the cash for living expenses and other necessaries of life. While recently there has been an expansion of the cotton crop toward the Southwest, which with the aid of fresher soil and mechanized means of production has produced about 40 per cent of the cotton since 1925, the bulk of the cotton is still being produced in the old cotton states where the rural Negro is shackled in the tenant system.

EFFECTS OF CRISIS

The effects of the crisis in the old cotton producing states of South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama give a pretty clear picture of what is happening to the Negro rural population of the South. In these states in 1925, 43 per cent of the crop land harvested was in cotton and tobacco and 41 per cent in corn, which was consumed on the farm. The tenant or share cropper cannot plant whatever he chooses, but must devote a given percentage of his land to the money crop from which the landlord gets his direct profit. The result is that corn and truck are very restricted, although corn is the staple food of the Southern tenant the year round. When the price of cotton takes a landslide it means that more cotton is necessary to pay off the debts for advances in food and cash from landlord and credit merchant, after the landlord has taken his 25 or 50 per cent, as the case may be. This year, with cotton at the five-year pre-war average and very far below the cost of production, the tenant not only must hand over his entire crop to landlord and merchant, but finds that he is still heavily in debt, and hasn’t a cent to live on for the winter, with the credit agencies closed to him. That is what is happening, not only in the old cotton states, but throughout the South, and that is the explanation of the demonstration of the 500 sharecroppers at England, Ark. In addition, the drought has ruined the corn crop in many sections, depriving the farmers of their bread.

DECREASE IN FARM LAND

In the old cotton states, the beginnings of the agricultural crisis were felt even before 1920. Since 1910 the area in farm land in the South decreased by 25,000,000 acres, and there are many miles of deserted farm lands throughout the cotton country. The tendency in the old Black Belt was for the richer lands in the plantations to drop out of use as some of the larger land owners were forced out by the crisis, and for the poorer lands of the small land owners to continue in use. Between 1920 and 1925 there was a decrease of 10,000,000 acres of improved land, despite the fact that 42,000,000 acres of farm woodlands were cleared, as wood-cutting was resorted to as a last desperate effort to keep going.

Of the 25,000,000-acre decrease between 1910 and 1925, 14,000,000 of these acres were in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi. Half of the 10,000,000-acre decrease in improved land was in this area. The shrinkage in the number of farms in the Southeast was almost entirely due to the dropping out of the farms of from 20 to 100 acres, farms largely cultivated by Negroes. While at the same time there was a tendency in the old Black Belt to divide the larger plantations into smaller tenant farms, there was a total decrease of 114,000 farms between 1920 and 1925. During the same period the cotton acreage was reduced by 4,000,000 acres. The decrease of 96,000 farms in the Southeastern states as a whole during this period was almost entirely due to the reduction of the number of farms operated by Negro farmers and tenants, 84,000 of the total being Negro farms.

While the farm crisis thus forced many thousands of Negro farmers to abandon their land and swell the army of unemployed in the cities, it also pushed the Negro farmer lower on the tenant scale. In the four old cotton states of the Southeast the percentage of croppers—the most enslaved of the tenant classes—among Negro farmers increased from 39 per cent in 1920 to 46 per cent in 1925. In 1920, during the period of inflation, the landlords were interested in more cropping, since they made more profit out of the half-share basis with cotton prices high. Between 1920 and 1925 many cash tenants and renters became croppers because they lost all their tools and work animals to the landlords and credit merchants when they could not pay off their debts in the developing crisis. Both small land owners and cash renters decreased during this period and entered the cropper class. Thus, while the farm population in this area decreased, the number of croppers remained the same, with tenancy on the increase. Between 1925 and 1930 this tendency was even more pronounced, and 1930 census figures will show a much greater increase in the percentage of tenants and of croppers.

OPPRESSION INTENSIFIED

With the development of the crisis, the feudal elements on the countryside are intensified, the small landowners are thrust into the tenant class, the cash tenants and renters into cropping, and with that exploitation and persecution are intensified. While the white farmers suffer in the same way, the Negro is always one rung lower on the economic ladder. The Negro landowner is forced to abandon his land, and a small white landowner takes his place. The decrease in the number of Negro farmers in the upper economic categories of the tenantry has been made up by the number of small white landowners entering this class.

Special attention has been given to the extreme four Southeastern states of the Black Belt, for it is here that the majority of the rural Negro population is concentrated. Here the tendency, even more accentuated during the past few years, has been for the Negroes to leave the countryside in increasing numbers, while the masses remaining on the farms are pushed into lower economic classes of the tenantry, under the lash of a white landlord and credit class. Today, more than ever before, the immediate cry is against starvation itself. In a “better” year, in 1928, the average total yearly income of a Negro farmer in Greene County, Georgia, including the crops sold and crops consumed on the farm, and also the value of wages for his work on the farm and earnings at other incidental work in the towns, was $399 for the whole family, slightly more than $1 a day. Lewis F. Carr, a bourgeois agricultural economist, places the average earning of a Southern sharecropper at 25 cents a day, the same wage scale as the East Indian peasant on the cotton fields, the Egyptian cotton-field laborer, or the Mexican peon. The same authority states that “in the South there are at least 7,000,000 people living on a family income of less than $250 a year, and 3,000,000 of these live on a family income of less than $150 a year.” This was before the industrial crisis of 1929-30, which in its turn aggravated the farm crisis. Today, the lowest level possible is being reached—starvation.

The demonstration at England, Ark., was a dramatic and concentrated expression of the revolt and struggle for food that has been going on for some time in the South. It had been expressed before, and is today, in the form of individual gun battles between landlord and tenant throughout many parts of the South. The revolt has reached such a stage that many plantation commissaries are double-barred and surplus stocks of food have been removed. The increasing number of dead Negroes found in woods and streams in the Black Belt, the large number reported in the newspapers being only a small percentage of the actual number, also tells the story. The increased number of lynchings is also a reflection of this situation. In the rural situation we have the basis for the development of a powerful mass self-determination movement.

DEVELOP LOCAL STRUGGLES

Our chief problem now is to develop local struggles in the Black Belt, based on immediate relief for the starving farmers. More than the general description, such as above, is necessary for the development of demands that will catch fire and burn in the correct direction. Forms of the organization of this struggle and the demands raised will depend upon the local situation and the development of our work, at which we have just made but a small start.

Our demands will probably group about two major issues: (1) the written contract or tacit understanding involved in the relationship between landlord and tenant; and (2) the credit system, which is also interwoven in the landlord-tenant relationship. Because the tenant is forced by his landlord to focus all his attention on raising money crops at the expense of food crops, he is left to the mercy of credit merchants and money lenders for his food supplies and other necessities. This also forces him to dispose of his crops at a forced sale, at much lower prices, in order to repay his debts. It is chiefly the merchant and the landlord who make these short-time cash advances, or advances in fertilizer, food, and clothing. Fertilizer, so necessary to the Negro farmer because the cash crops year after year exhaust the soil, is his primary expense. He pays an average of 37 per cent interest on fertilizer credit, and an average of about 25 per cent for advances from merchant and landlord. His whole crop is given as security. Thus, from many sides, the Negro farmer is chained down and becomes a virtual peon.

THE CROPPER CONTRACT

The contract, as it functions in the South, is a subtle form of forced labor, which carries with it the threat of imprisonment for non-payment of debts and gives the landlord a lien on the tenant’s crops. It is enforced by the whole police and court system, working hand in hand with the landlord. The cropper, who is furnished with all his tools and work animals by the landlord, who in return gets 50 per cent of the crop, is thus entirely at the mercy of the landowning class. This is even more true of the Negro cropper, whose caste position leaves him absolutely no avenue of escape. A demand such as a collective contract between the tenants and croppers on a large plantation on one hand, and the landlord on the other, at the beginning of the season, as Comrade Tom Johnson suggests, similar to a wage agreement between a union and a boss, might be an excellent focus point for developing a struggle. This is only possible, however, in the large plantations, chiefly concentrated in the delta regions.

The complicated economic class divisions among the lower strata of the farm population do not offer as many difficulties in organization among the Negro farmers as one would suppose. There are five classes of tenants in varying degrees of dependence upon the landowner. Among the Negro farmers this is not of such great importance, since the line of demarcation is not very sharp and the common struggle against the white landowner and the system of “white superiority” will have a tremendous cementing influence. The line is also not as sharp between the small Negro landowner and the Negro tenant, because even at his best, the Negro landowner is fully dependent upon the white superior, on whose land he is often forced to work in order to supplement his meager income. The Negro farm population is a very compact economic group, not very seriously hindered by tenant class divisions, and therefore a tremendous revolutionary force on the countryside. These complicated economic divisions, however, offer many serious difficulties in uniting the white and Negro farmers, for they, to a large measure, are at the basis of white chauvinism on the countryside, aggravated by landlord and credit merchant.

COUNTRY-CITY INTERCHANGE

There is another factor of extreme importance in the Southern agricultural situation which will be of great help in the development of a proper movement for self-determination. According to the United States Department of Agriculture, 50 per cent of the Southern tenants move every year. There is a continual stream from one farm section to another, into the cities and back from the cities. This together with the fact that the Southern proletariat, especially the Negro, still has one foot on the soil, will help tremendously in combining the proletarian and agrarian movements. With the development of a revolutionary movement in the cities, the Negro worker will carry his experience back into the country. This intimate relationship between city and farm worker also makes it necessary for the Party immediately to start work on the farms, guaranteeing ourselves a revolutionary recruitment at the source of Southern labor. While this constant fluctuation is unfavorable from the point of view of building stable organization on the countryside, it is extremely favorable in that it will guarantee the hegemony of the city proletariat in the struggle for self-determination.

This factor is also of great importance in overcoming what I think to be our greatest difficulty—white chauvinism among the white workers and farmers of the South. There is always present the danger that the bourgeoisie will succeed in making the struggles in the South take on the character of race warfare unless we make greater advances in organization among the white workers than we have done to date. This is fully recognized by the white ruling class, which constantly harps on this distinction in its campaigns against us. In the development of the self-determination movement this danger looms greater than elsewhere. It is therefore a prime necessity that the revolutionary movement be developed among both white and Negro workers. In this connection it is also of prime importance that the movement of the industrial Negro and white proletariat be speeded into more power and greater intensity and in this manner retain hegemony over the agrarian movement.

One would naturally suppose that this would be an expected development, but the chronic character of the farm crisis and its growing severity may drive the farm population to revolutionary action before the city proletariat. The migratory character of the white tenant, as well as the Negro, will act as a levelling process in combatting the white chauvinism on the farms by bringing the experience of white and Negro solidarity in the cities to the country. Above all it is necessary to assure the hegemony of the proletariat, in order to give firm and correct leadership to the movement, combatting chauvinistic expression.

For the immediate present we should aim to develop our farm movement in the areas immediately adjoining Birmingham, the greatest industrial center of the South, and in the heart of the Black Belt. It is here that our work among the industrial workers and among the farm workers can complement each other in the development of not only a movement for self-determination but of our entire revolutionary movement in the South.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v10n03-mar-1931-communist.pdf