Five years after the repression began as the U.S. entered World War One in 1917, many political prisoners remained in jail. Robert Minor, one of Tom Mooney’s foremost champions, on U.S. culture of arrest and jail.

‘Let’s Get Them Out’ by Robert Minor from The Liberator. Vol. 5 No. 5. May, 1922.

I HAVEN’T been in jail “on my own hook”–the only prison that I know from the inside is an old-fashioned little shack on the Rhine. It has damp stone walls of a homespun quality with cracks running crooked ways and mortar falling loose. It has individuality–that jail.

Ben Gitlow’s jail is a damned, soulless, characterless, hygienic, concrete-poured cross between an East Side model-tenement flat and a Child’s restaurant. There is not even a fly-speck, a spider web, nor a picturesque leak marking the ceiling that you can fasten your eyes on. It is as monotonous as the inside of an enameled wash-bowl.

The god of prison is monotony.

One of our labor prisoners tells me that the first six months in this God-curst, model, mechanical flat a man gets awfully interested in his new friends. But after six months you learn that they are just as mean as the people outside, as sordid in their thoughts. And then the little mystery there was in life goes away and leaves it. You live on the inside of this iron tub more listlessly each day.

Did you ever hear a laugh ringing through the iron walls of a penitentiary, knowing that that laugh comes from a man condemned to death? Well, a lot of the best-natured fellows in this world couldn’t laugh over again unless they laugh that way. Do you remember when the dicks’ torture of Andrea Salsedo ended with Salsedo’s corpse tumbling from the fifteenth floor window to the sidewalk below? You may recall that Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti started public protests against this horrible death of their comrade, Salsedo. And you may remember that Sacco and Vanzetti were caught, arrested for daring to protest, were questioned as Reds, and then thrown into prison and condemned to death on a charge of highway robbery and murder, with a long string of hired witnesses–just a repetition of the Mooney case.

“Hah, hah, hah, hah”–I hear the happy Italian laugh through the Dedham jail. The laugh has a mechanical, scraping tone like a phonograph, because of the iron and concrete jail walls. That is Niccola Sacco laughing.

There is Big Jim Larkin, the giant leader of the workers. of Ireland, whose life is being blotted out in Comstock Prison, while the British Nero snares the Irish race that needs him. There are the keen, clear-minded Ferguson and Ruthenberg and Winitzky, Alonen, and so on, and so on, enchained in prison here in New York State.

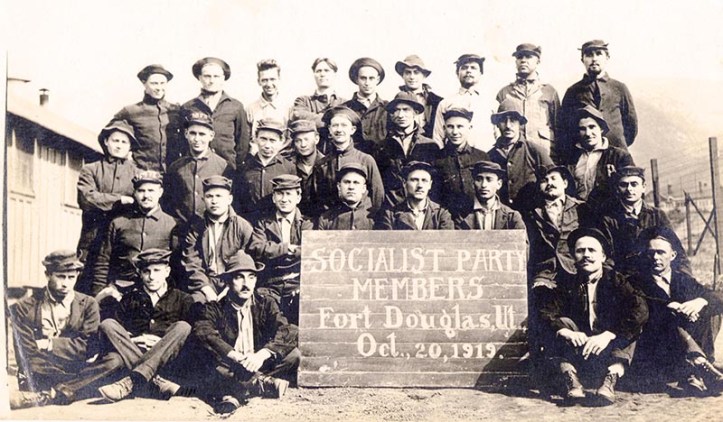

There are Frank Keeney and Fred Mooney in West Virginia, with all the other decent men of Labor that could be caught with them, threatened with jail for murder, treason and various other types of crime. There is Alexander Howat jailed in Kansas. There is the old, old crime of California, where Sam Quentin and Folsom prison walls are bulging with the heavy load of Labor’s prisoners. There are eighty-nine members of the Industrial Workers of the World in Leavenworth, many lying broken and hopeless after five years’ torture for the crime of organizing workers.

See a fellow dreaming dreams of something better in a lumber camp of Idaho? See a man with his eyes flashing, rising in a union hall in Tennessee, to turn his voice loose on some sort of thought with substance in it? These two guys will soon be stuck away in that bedbugless flat somewhere–that sanitary, soulless, fleckless, womanless hell of concrete and iron.

Ben Gitlow says he thinks we ought to begin on Tom Mooney, that we ought to let Tom Mooney’s case be the first pivot of our fight, for Mooney and Billings have been in now since July, 1916, and being in a death cell awaiting the noose is a rather heavy form of imprisonment. And more particularly–the Mooney case furnishes the most striking example of what a “labor case” is. It is a little cameo, a little standing example of the labor movement in America.

The typesetters of labor papers have got tired of setting the 72-point type for the name Mooney, and all over the world, through sheer fatigue, thousands of persons are persuading themselves “Well, now he will get out.” And when I pick up a letter from San Francisco, almost thinking I might hear some inkling of good news, I learn that five more labor men are about to be sent to the penitentiary in California.

At the time when everyone was terrorized and silent, a man came over from Oakland to San Francisco, the editor of the Oakland World, a Socialist Party paper, and got into the fight for Tom Mooney. This meant a lot at that time. A lady of the neighborhood was writing to all inquirers in the party private letters stating that Mooney was guilty, and an Anarchist anyway, and should not be defended by Socialists. But–it is a thing of the past.

In the midst of this night of terror, a few other breaks of light came through. Eugene V. Debs wrote and offered his name and help. And Snyder, editor of the Oakland World, plugged away, fighting day by day in his able newspaper style for the Mooney defendants. And no, they are not releasing Mooney–they are putting Snyder into the hellhole of a penitentiary–and four more of his kind.

Those of us who live in America have a peculiar situation before us. Step back and get your breath and look around the distances. You will see that all of the political prisoners are let out in nearly every country in Europe. Why is that? They are let out in Europe as a matter of course, automatically, as political routine. As soon as the crisis which caused their imprisonment has passed over, they are let out. Everybody on earth, except the peculiarly dirty political hypocrite type, which is the unique curse of America, knows that in the struggles of the classes for domination, men who are imprisoned for acts or words used in that struggle cannot be regarded as criminals. At least, those that are fighting for the cause which is to dominate in future cannot be regarded as criminals; only reactionaries can be regarded as criminals. European politicians do not like to admit this, but they have to. As a matter of automatic decency, which they know they have to concede, the European politicians release after every war or revolutionary outbreak every person who got into prison as a result of espousal of the working-class’s cause. We want to catch up with Europe in this respect.

We want all working class prisoners in American jails let out. Every one of them. Every man who got into prison as a result of any phase of the class struggle, of the labor struggle, of strikes, lockouts, fights, quarrels, words, opinions, political speeches, writings of manifestos or what not. We want Tom Mooney out, we want Sacco and Vanzetti out, we want the 150 I.W.W.’s out, we want to keep the West Virginia coal miners out, and the Kansas coal miners. We want to keep Snyder out. We want Matthew A. Schmidt out of San Quentin, and Dave Caplan; and we want McNamara out–yes, we want the American Federation of Labor prisoners, and the I.W.W. prisoners, and the Communist prisoners, and the Socialist prisoners, and the Anarchist prisoners, that are being thrown into jail or beaten up or murdered for organizing coal diggers in the non-union fields.

We want a united, single drive to break down this smug, reeking, stinking, institution here in America–the institution of jailing everybody for the best part of his life, for daring to speak or act for the working class.

The Liberator was published monthly from 1918, first established by Max Eastman and his sister Crystal Eastman continuing The Masses which was shut down by the US Government during World War One. Like The Masses, The Liberator contained some of the best radical journalism of its, or any, day. It combined political coverage with the arts, culture, and a commitment to revolutionary politics ay a pivotal time in Left history. The writings by John Reed from and about the Russian Revolution were hugely influential in popularizing and explaining that events to U.S. workers and activists. Increasingly, The Liberator oriented to the Communist movement and by late 1922 was a de facto publication of the Party and was sold to the Party by Eastman. In 1924, The Liberator merged with Labor Herald and Soviet Russia Pictorial into Workers Monthly. The Liberator is an essential magazine of the US left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/culture/pubs/liberator/1922/05/v5n05-w50-may-1922-liberator-hr.pdf