A fascinating look at the very specific development of farming in Argentina.

‘Capitalist Agriculture in Argentina’ by Ernesto F. Dredenov from International Socialist Review. Vol. 13 No. 8. February, 1913.

THE Argentine Republic is comparatively a very young country, its rapid development dating back only about 25 years. As the country depends mostly upon agriculture and as only one-third of the total area is under cultivation, one should think the conditions for the small farmer and farm laborer ought to be excellent.

But the man who believes that, forgets that capitalism is near to its climax and therefore has its claws upon everything.

How different was the colonization of the United States some 60-70 years ago, when capitalism was in its early stage of development, from the present day well organized capitalistic colonization in Argentina.

In the United States at that time anyone who had strong arms could go out west and occupy a piece of free land, more than sufficient to nourish him and his family. In Argentina, although two-thirds of the country are “unoccupied,” there is no more room for a man with only strong arms, except as a beast of burden.

Today, big land companies, mostly branches of railroad companies and backed by an enormous capital, send their agents out west to select immense areas suitable for agricultural purposes. As these companies go hand in hand with crooked government officials, they obtain large territories practically for a sandwich. As soon as they are in possession of the property title, they build a railroad across their estates, which, of course, raises a hundred fold the value of the land. When the company considers the prices high enough, it sells the land at public auction.

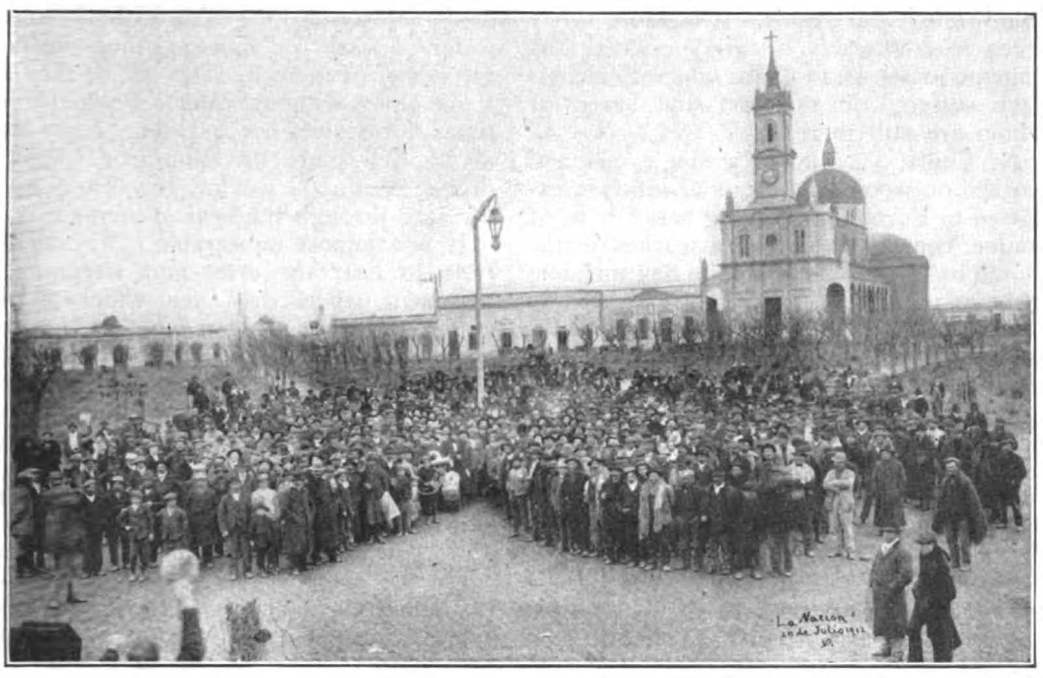

In order to stimulate keen competition, the sale is advertised in every newspaper during three months in advance. On the day of the auction the company runs special trains, free of charge, even if the place is several hundred miles from the federal capital, Buenos Aires. Secret agents (drivers) do the rest in artificially pushing the prices. Now as in Argentina it is necessary to have at least several hundred acres of land to do fanning in an economical way, it is clear that the man who has nothing more than strong arms, will be out of place, even if the land is sold on easy payments.

No doubt there are thousands of wealthy men who came to the country without a cent; but this was 20 or 30 years ago, when 100 acres didn’t cost more than one costs today.

Suppose a man after a number of years has been successful enough to become owner of a small farm, he still has a hard struggle against capitalism, in which he finally must lose. The big landowner who can afford to use the most perfected and powerful machinery, is enabled to produce the cereal, or most other agricultural products at a lower cost than his small neighbor and therefore can sell them at a lower price than the latter. Here, like everywhere in the economical field, the strong tries to destroy the weak.

Also from another side is the existence of the small landholder threatened. If the capitalists do not control his ground, they certainly control its products. At the present time there are about six big cereal buying concerns, so it may happen that the agent of one concern offers a few cents more for a bushel than another. But before long the world’s cereal trust will be organized and then the days of the small farmers are counted. The trust offers prices which just allow a living to the farmer, who is forced to sell his products to the trust or else incubate them. As the price must be based upon the cost of production of the farmer’s method, the big landowners escape again because they make still good profits on account of their economical way of tillage.

In no time in the past have conditions for exploitation in agriculture been so favorable as at the present day, and all the so-called progress in this line during the last centuries were for the interest of the exploiters. During the period of slavery, the slaveholder had to nourish the slaves and care for them during the winter when there was no work, or in time of sickness. The wage slaves of today have to tramp over the country during winter and beg for the permission to work or for a piece of bread.

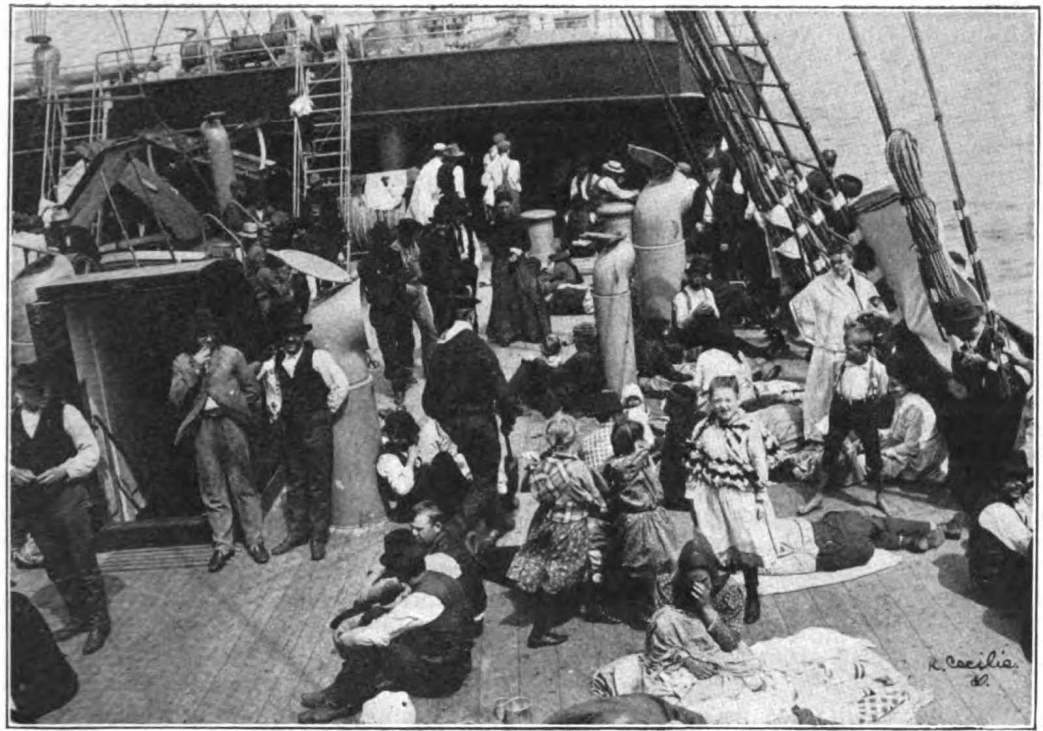

The conditions become sometimes so untenable in Argentina during the winter, that thousands of workmen leave the country. In July, 1912, the emigrants exceeded even the number of the newcomers by 1,500. The steamship companies promptly take advantage of this state of things and charge as an inducement only $22 for the passage from Europe but $36 to Europe, because a good many of the immigrants are bound to return by any means.

On the other hand, the present day means of communication and operations of commerce make it possible for the capitalist to exploit millions of acres of land without the least trouble for himself.

He knows, perhaps, no more about agriculture than a cat does about Sunday. He may live in Buenos Aires, Paris or Bermuda enjoying life to the limit, while his manager whom he interests in a small percentage of the net profits, will arrange everything for him.

Under these conditions big companies are formed to still more intensify the exploitation of the land, which are therefore better adapted to outdo the small farmers. To this end only lately three land companies have organized—Sociedad Forestall Lda, the Cia de Tierras de Santa Fe and Sociedad Quebrachales de Santiago—have joined their forces together; they own 2,000 square leagues, more than 12,000,000 acres of land. Argentina imported during 1912, $6,000,000 worth of the most up-to-date agricultural machinery to be used on these monstrous estates.

There are a good many ranches of 50,000 to a 100,000 acres that use several hundred men during the summer months. The best ranch the writer found during his long journey through Argentina, is one of 150, 000 acres in the most fertile region of southern Santa Fe. The workers got $26 during the six summer months, of which $10 were kept back until the summer was over, so that those who left before received only $16 a month. The bosses called this arrangement a kind of a saving bank, but it certainly was something else. The most striking difference on this ranch was between the horse stables and the men’s sleeping quarters. The former were high and airy buildings, while the latter was a small room without windows, where three “beds” (two beams and three boards), are placed one above the other. The only excuse for these bad conditions is that the owner hasn’t spare room on his ranch. Horses cost money and men don’t. This explains the difference.

The owner of the ranch, the Norwegian consul and a very wealthy man, is the same man who financed the South Pole expedition. I wonder whether Amundsen, who stayed for some time on that ranch, found out who really financed the discovery of the South Pole.

On these big ranches hardly any women are employed except as cooks, so only single men are accepted and if they are married their wives must stay away. Only a few watchmen, whose little houses are scattered over the estates, are allowed to keep their families with them.

Here, like everywhere in the world, Socialism will come too late to break up the family. As a consequence of these unnatural conditions, there is a house of tolerance at every second or third railroad station where this system of capitalistic agriculture is in practice. At some stations it is, beside the shanty of the policeman, the only house in the neighborhood. And as a true capitalist country the Argentine Government asks licenses ranging from $500 to $5,000 a year. Nobody must be surprised, then, that it happens that immigration officials offer to young newcoming girls, easy positions with nice dresses and plenty of money.

Not always do the ranch owners refuse married people. For instance, down in the territories of Santa Cruz or Chubut in the sheep raising regions, they are welcomed. On account of the difficult traveling, married couples do not move away as readily as single men, when they are tired of the loneliness in the Patagonian steppes.

Another form of capitalistic agricultural exploitation are the so-called “Colonias” which rent out their land in parts of 200 to 1,000 acres. The rent usually has to be paid half in advance, so that the owner is always in safety, no matter whether there is good or bad harvest. For all debts the renter incurs he must pay 12 per cent interest.

The writer of this article has been several months in the administration of such a colonia and was witness of an incident which showed most evidently that the renters are robbed of the fruits of their work like the wage slaves. The proprietor of said colonia, which aggregated about 90,000 acres (who owns in all more than one-half million acres in several parts of the country), bought that land some 25 years ago for less than one-thousandth of its present valuation. Laborers of probably all European nations who built a railroad across it from the sea coast, brought it to its present worth.

A renter on this colonia had very bad harvests for two years in succession and, of course, the poor harvest of the third year wasn’t sufficient to pay his debts. As the renter was also heavily in debt with the storekeeper, the majordomo (manager) ordered him to bring his wheat to the colonia’s barn, and appointed an assistant to the effect that the order was carried out. The renter who considered his debts with the storekeeper, who provides him on credit with the means of living during the winter, started to bring at least a part of the wheat to the latter, which the assistant reported at once to the administration. When the majordomo arrived, drunk at night, and heard of this crime he threatened to put in the renter the fear of death. He had two horses saddled and went out with an assistant into the dark night to the shanty of the renter. Arrived there he actually discharged his army Colt twice into the roof of the poor man’s home, who came out to answer the two shots. Thereupon the majordomo and his man slept upon the wheat bags in order to prevent their being taken away during the night. The next morning the wheat was brought to the depot of the administration.

As the value of the wheat wasn’t sufficient to pay the rent for the last three years, the majordomo gave orders to the sheriff in the next village to seize the belongings of the poor farmer, that is to say, to do the robbing “legally.” A few days later the sheriff came, accompanied by a policeman armed with a rifle, and a whole gang started for the renter’s home. The latter was absent and only his wife, his young daughter and a few children were at home.

The woman protested and the children cried, but nothing could help. On the contrary, when the poor woman in her excitement tried to prevent the sheriff from opening the corral of the horses, the policeman pushed her against the breast so that she nearly fell to the ground. The wolves drove away all the horses they could gather, 21 in all, a binder, two wagons and a number of harnesses.

So it happened in 1912 in Canada Mariano in Argentina, where millions of acres are waiting to be broken up. On that particular colonia or immediate neighborhood about 25 or 30 seizures have been made; in whole Argentina they probably amounted to tens of thousands among the farmers during the harvest.

Last year (1912) two regular farmers’ strikes occurred consecutively in Argentina, during which a good many farmers emigrated to Brazil or Uruguay.

The first strike started in July in the provinces of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe, and lasted over three months, and the second one started at the beginning of November in the province of Cordova. It is not ended at the time of writing this. Although most farmers had contracts for several years, they went on strike. Why? Because they had nothing tb lose. Many have had their harvests seized several times; one, Matias Tustrivo by name, even seven times.

Best will be understood as to how these people are sucked by bringing up a few of the demands formulated by the striking farmers:

1. To be free to sow the seed they consider best.

2. To be free to thresh their cereal with the machine they judge most advantageous.

3. To be free to sell the harvest to whom they like.

4. To be allowed to raise poultry, six pigs and the necessary number of milk cows for their exclusive use without giving part of it to the owner.

5. Obligation to the owner to secure a shelter, etc., etc. (Newspaper La Argentina, August 4, 1912.)

To make a worthy finish of this agricultural exploitation we reprint without comment a report of the Buenos Aires Standard of February 15, 1912, which is certainly no labor paper:

“The Argentina press denounces that slavery practically exists in the North. This is in obrajes or plantations of the Chaco and the yerbales. There, it is said, hundreds of lives are sacrificed annually to make a little extra profit. The men, owing to distance from the seats of labor supply, go on contract and once there are sweated with impunity and under threats of force. They cannot get at any official to complain and cannot escape, as traveling alive in the forest means death by starvation, Indian attacks or wild beasts. The Department of Public Instruction has officials there who have called attention to this slavery. Orphans are enslaved and nothing is done to improve or educate them. The National Labor Department, as usual, has no knowledge of what is going on and limits itself to sending emigrants to places whence there is no return.”

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v13n08-feb-1913-ISR-gog-ocr.pdf