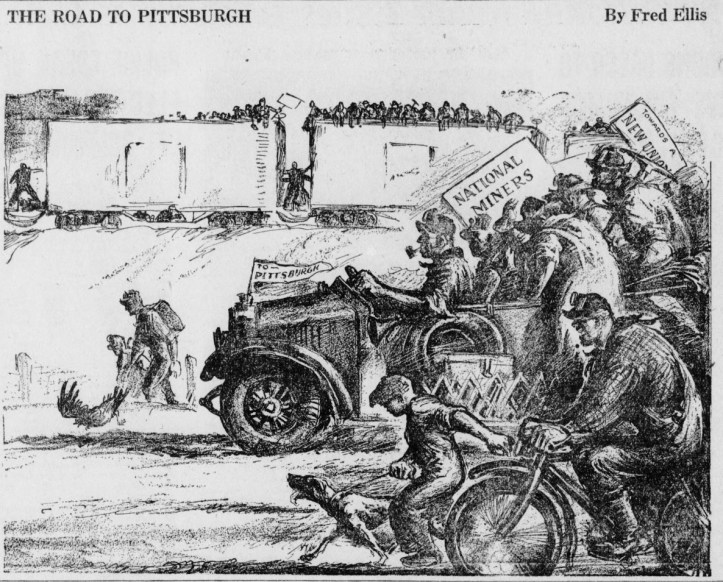

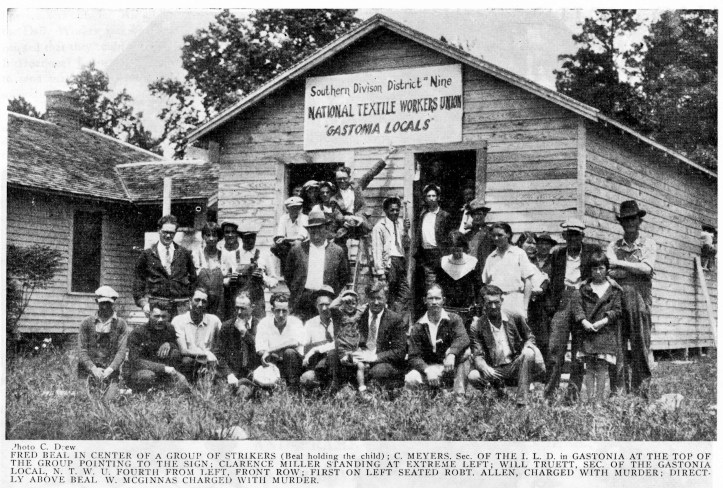

The political culture and working class struggles of a key period are brought to life through the language and concerns of some of the six hundred participants in Myra Page’s record of 1929’s Cleveland Trade Union Educational League convention. That meeting brought together the new unions, particularly the miners and textile workers, that had recently developed and formally transformed the T.U.E.L. into the Trade Union Unity League, switching its focus from an industrialist opposition within existing unions to the builder of independent, ‘revolutionary’ unions of the so-called ‘Third Period.’ Myra Page was born into a progressive, middle class Southern family. Introduced to radicals through the Rand School, including Scott Nearing, she was one of group intellectual women who who became union organizers and Communists, most importantly starting the Labor Research Association. For both her doctoral thesis and as part of work with the movement, she investigated emerging Southern industry and conditions among workers in the South. She would be particularly involved the bloody, hard-fought Gastonia strike of 1929, the Communist Party’s first big campaign in the South, where theory found practice, for better and for worse.

‘Cleveland—A Mass Story’ by Myra Page from The Daily Worker. Vol. 6 Nos. 214-216. November 13, 14 & 15, 1929.

I.

This is the story of the six hundred and ninety delegates who made labor history at the Trade Union Unity League Congress, which met in Cleveland on August 31-September 2, 1929. It is their story, jotted down as they told of it, of their working class experiences which had forced them and their fellow workers into struggle against the bosses, and roused them to send their representatives here to organize a revolutionary trade union center in the United States.

This mass story should be written down, as far as possible, so that American workers who could not attend will know how genuine an outgrowth of themselves their new union center is, and how it marks the beginning of a new era for American working class. As one high point labor’s epic of struggle from slavery to freedom, Cleveland is a story without beginning or end. Its roots run far into the past, and its triumphant climax remains for us to write in the years which lie ahead.

I am giving the story as it came to me, in fragments from workers’ lives and flashes on to labor scenes which, when brought together, form a massive, stirring whole.

The first session of the convention I sat between a miner’s wife from Superior, Pennsylvania, and a young Negro auto worker, from Detroit. She was a dark little woman with a baby in her lap which alternately threw itself bodily to and fro, up and forward, gurgling at the ceiling, and then, tiring of this game, whimpered and fumbled for its mothers breast or pulled her hair. The woman bounced and whispered to it, and gave it the breast, meanwhile attempting to take notes and hear all that was being said. Those fifty miners’ wives who had sent her here as their representative from their woman’s auxiliary of the National Miners’ Union would want to know everything that had happened. She and her husband and baby had traveled all night in a truck with fifteen other miners and their wives and small children.

BIG FAMILIES, NO WORK.

Conditions back there were something awful, she said. Men with big families to support and no work for months. Others with two or three days a week, and that not regular. Her man had been luckier than some. But most, their kids were wanting for shoes and coats and crying for bread. The U.M.W. had gone to pieces, since Lewis sold out the strike, and men were nigh desperate when the new National Miners’ Union and Workers International Relief came. Now they were pulling themselves together, and with everybody jes’ sticking, and other workers backing them up, the miners and their wives would fight these bosses to a finish.

Jim, the well-built young Negro on my right, told of the ferocious speed-up on the belt in Ford, Packard and other plants where he had worked, and the rising tide of revolt among the tens of thousands of auto workers in Detroit, leading to spontaneous walkouts and the formation of a vigorous Auto Workers’ Union there. Yes, there were many hundreds of colored men in the industry, and they and the white were fighting along side by side. High time they got together, too.

Everybody was on their feet, as Foster mounted the platform and declared the convention open. Cheers and lusty singing of the International. We looked around. The hall was filled, both floor and galleries. There were many familiar faces. Sam, formerly a wobbly organizer at seventeen years of age, now following his machinist trade in a midwestern city and carrying on revolutionary work among his shop mates. A conference of 150 unorganized workers had sent him to this convention as their representative. When, six weeks before, Sam had gone to this town to work, he found the hundreds of metal workers there totally unorganized, without a union, shop committees or revolutionary organization of any kind. Now, shop committees had been established in a half dozen plants, a shop paper was appearing each month and getting wide circulation; an active local of the Communist Party, with seventeen working class members was directing the work, and big mass meetings of workers had proven so successful that the American Legion and city government had undertaken to drive Sam out of town. But he was still there, grinning. Fired from one shop, he found work in another. Ask Sam if the workers were ready for action, just given the lead!!

Louise, an auto worker from Detroit. A little firebrand, carrying on effective work, especially among women. Bill, looming above the crowd–railroad switchman, and president of his local union, which under his leadership was building its membership and successfully defying the reactionary dictates of the International and A. F. of L. officials. Henry, employed in the Great Northern shops, where unions had been smashed after the 1922 strike, working to reorganize the men on a firmer, more militant basis. Angelo and Mary, needle pushers from Philadelphia, whom I had not seen in seven years. And many others. These were the type of workers who had been chosen by their shop mates to represent them at this convention. Close to the rank and file, coming right from the job and class struggle.

Never had I seen so many young faces at a labor convention, or so many women and Negroes. And so many cotton dresses and work shirts! It was going to be different, all right, from an A.F. of L. or Amalgamated Convention, where middle aged men, in new suits and stiff collars–fat-bellied officials and skilled workmen from labor’s aristocratic upper-tenth–pretended to legislate for American labor. Here at Cleveland was American labor, straight from shop, mine and field. No longer were the officials to be allowed to speak for labor, it would speak for itself. What would it say, what action would it take? A silence fell over us, as Foster began the keynote speech of the congress in his quiet, analytical way. We stretched forward, straining to hear every word. There he stood, a former railroad worker, leader of the great steel strike, and our trusted organizer. At his back was a silly painting of a middle class estate, while overhead hung the red banner. The stage scenery had a grotesque familiarity. What labor convention in the United States ever lacked this misplaced element! Nevertheless, this time we would make a symbol of it–labor stepping forth from capitalist society and pronouncing its doom.

In simple, forceful language Foster told how things stood, in this “land of the free,” for the toilers. Here we were, pitted class against class. The rich getting richer and the poor poorer. Speeding up beyond physical endurance, in order for capitalists to get more profits out of us. Then the broken ones cast to the dump heap. Rationalization throwing four millions out of work. Imperialist war threatening. And everywhere in the capitalist world workers suffering like this and fighting against the bosses’ greed. Only in Soviet Russia, where workers had taken power, were things different. In America, the masses of labor, betrayed by the A.F. of L. and the “progressives” were rising in revolt. A strike wave was under way, Gastonia, Elizabethton, Marion, New Bedford. The miners’ battles in Pennsylvania, Illinois, West Virginia. Auto mechanics striking work in Michigan and California. Shoe workers strikes in Boston and Lowell and those of food workers and needle trades in New York City. Everywhere, walkouts for workers’ demands.

We were here to organize and lead these revolts to build a powerful v revolutionary union center, to fight against capitalist speed-up and race discrimination, to organize the unorganized, fight American imperialism and its war danger, and defend the Soviet Union against its capitalist enemies. We were here to man and direct the struggle of American labor against capitalism and for a workers’ society.

Once again we were brought to our feet as representatives from the Gastonia strikers filed onto the platform. A slip of a girl, a gaunt, middle aged woman and a young boy.

Daisy MacDonald stepped forward to speak. “I’m mighty glad to come to this convention, as representative of the Gastonia locals of the National Textile Workers’ Union, to tell you how much your backin’ us up is helpin’ us strikers there in the South. How much we appreciate it. And if ever you need it, we’ll do the same by you. All of us working people must stand together. And we want you to know that whatever the bosses do, we’re goin’ to stay by the union and stick until we win our demands.

“Now I want to tell you somethin’ of why we went on strike an’ what we’re fightin’ for…Mothers with small children have to go into th’ mills to work for twelve hours, all night. My husband and I had to leave our little ones at home, alone…No chance or place to sit down, all night long. Men gettin’ ten and eleven dollars a week. We couldn’t give our kids th’ ejication we want ’em to have. They have to stay ignorant. We jes’ barely did live. No coal, jes’ wood. And it was worse for th’ colored folks. Colored women sweepers getting seven dollars a week, where I worked. And they’ve got the same problems as we white workers have. They got to live and raise their kids. So we should stick together, and help one another out.

“When the union come, we know it was for our good, ‘n we signed up.

“The bosses tried every way possible to break up our union. But they couldnt do it. Police. Arrests. Turning us out of homes into the streets. Spies. Promises. Threats. Nothing broke our spirit. We only fought harder. Then they decided to git our leaders.” (The story of the June days followed.) “So now we got to fight harder than ever, to free our leaders’n build our union. And with your ‘n the laboring people’s help everywhere, we’ll win.”

Later, in private talk, she said, in a quiet, matter-of-fact voice, “If the jury decides against us, ‘n they try to send our leaders to th’ electric chair or give ’em long sentences, afore we’l let ’em do it, there’s goin’ to be a war down thar.”

When questioned, she told us she and her family were living in the union tent colony. She and her husband were blacklisted, and until the union won recognition they couldn’t get work in any mill in the Carolinas. “But this is better than it was afore. We had nothing to lose, anyhow. We barely could live. Now we’ve got something to work and fight for in life.”

II.

After a needle trades delegate from Baltimore has related the tremendous growth in the left wing movement there, among both organized and unorganized in various industries, and the common struggles being made by colored and white, a young chap with a southern drawl who hailed from the port of New Orleans, took the floor. With all the tang and swagger of the sea, he described in the sailor’s lingo, the conditions along the southern gulf coast for men who go down to the sea in ships, and likewise for those who load these vessels with cargo. Rottening food, bunks unfit for animals, quarters below water level and lacking any ventilation. Tyranny of ship and dock officials. White worker played against black, and black against white. Since the International Seamen’s Union had lost all fighting character, the men had been helpless before the shipowners’ onslaughts. But now the Marine Workers League was reorganizing them, on a sounder basis, and we could expect to see the big battles in many ports within the next few months. “You all know how important marine transport is in modern times. We marine workers know that we’ve got an important part to play in labor’s struggle to victory and we’re in to the finish. You’ll all live to see the American ships in every port flying the red flag!” For that statement we gave him a good send-off.

A red-faced, broad-shouldered lumber-jack from Seattle spoke of bad conditions in the North West and the revolutionary traditions of labor there, ending with the statement that Seattle labor would call other general strikes like the one of some years ago, but this time with more telling effect. “And any time Soviet Russia needs help, Seattle labor is ready!”

A girl silk worker strode back and forth on the platform, and described for us in a ringing voice the Pennsylvania textile workers’ battles against terrific conditions, state police and reactionary union machine, the birth and growth of the new revolutionary union there, and instances of solidarity between miners and textile workers.

The exploitation of Japanese, Mexican and Chinese workers on the California fruit farms and in the canneries was the story which a bright-faced young delegate from the food workers’ organization on the coast had to tell us. He made a strong plea for interracial and international solidarity of workers both within the country and all over the world.

A slim, soft-tongued mill hand from Dixie told more about mill conditions in the South and the rapid growth of the National Textile Workers Union throughout the Carolinas, Georgia, Virginia and Tennessee. Many mill hands were serving as volunteer organizers, working their way from mill village to village, organizing mill committees, and preparing the way for widespread revolt. “We mill workers down. South have got no use for the UTW. That organization has sold us out, time and again. It works with the bosses. But we want a real union, and we’re going to build the National Textile Workers Union into a powerful organization. At first, many mill hands thought Bolshevik was somethin’ to eat them up, but we’ve learned different. That’s bosses talk. We found out Bolsheviks were fine folks, who helped the workin’ people. We used to hate’n despise the colored people but we’re learning different on this, too. All workers got to stick together for their interests. Bolshevik means a worker who woan mind th’ boss. We ain’t ashamed to be called Bolshevik, we’re proud of it. We used to be jes’ Poor Whites, who let th’ mill owners bleed our lives out, but now we’re Bolsheviks who’ll fight back!”

When noon-time came, nobody wanted to quit, or leave the hall. So we stayed inside and ate sandwiches and drank pop, and about a hundred gathered around the piano and sang, every working class song we knew. Two or three hundred more sat in the benches and joined in.

“It’s the old capitalist system–

It ain’t good enuf for me.

It’s good for the money makers-

For Wall Street speculators-

For all the labor fakers–

But t’aint good enough for me.”

Also the Hurry Hymn of the Ford Worker:

“Mine eyes have seen the ‘glory’ of the coming Ford, “t’s made under conditions that offend even the lord. With most ungodly driving and amid a mad uprear, PRODUCTION rushes on! Hurry, hurry, hurry up, John!

Hurry, hurry, hurry up, John!

Hurry, hurry, hurry up, John! We’ve got a rush job on.”

Not many knew the words at first. Maybe a third of us knew the International. But everybody threw themselves into learning the songs just as earnestly as they were setting themselves the task of mastering the theory and tactics of proletarian revolutionary struggle. We had such a good time singing that when Jack Johnstone, with his cox comb hair, appeared on the platform to open the afternoon session, nobody wanted to stop. He had to wait until we had one or two more.

Just as had happened in the morning, two of the best speeches in the afternoon session were given by Negro delegates. This was no accident, for weren’t colored workers in a position to feel the struggle the most? Who could know better than they the need for workers’ solidarity against capitalism? And when they feel a thing to be true. colored people surely know how to express it, in music or by word of mouth. What ninnies the “progressives” are, to try and patronize colored labor!

A Negro miner who wore a red flower in his buttonhole and came from Logan County, West Virginia, where the civil war between operators and coal diggers raged a few years ago, began his talk by saying:

“I’ve heard a lot about colored workers here today and that’s all right; but I want to tell you that I’ve come to this convention and entered this movement not as a member of a race but as a member of the working class. What difference does it make what’s the color of your skin? It’s all the same to the boss. What he asks, when you go for a job is not ‘what race do you belong to?’ but ‘how much coal can you load?’ Down in West Virginia, we miners, white and black, have learned our lesson. We stick together. We’ve learned to depend on ourselves, and our National Miners Union. We’ve got rid of the Lewis gang. and we’ve quit praying to that fellow up in the sky who some still believe in. That’s what all of us workers has got to learn to do, depend on ourselves and the men we choose to lead us.”

A mulato woman, with a chesty voice and sweeping gestures, drove home point after point, urging us, also, to depend on our organized power alone, and break away from the religious bonds which hold many of the working class back. “I used to be religious, myself,” she went on, “but what’s been happening among us miners in Illinois for the last ten years, and all over the country has changed all that. What good does religion do a worker, anyways?” she challenged. “Only deceives him and holds him back. Keeps him from fighting the bosses. That’s why the bosses are for it. Down in Texas the other day a black man got down on his knees and prayed for deliverance from the white mob which had him, but they soaked him in oil and burned him just the same on his knees. I tell you we workers got to git off our knees and fight.

“Will religion feed us and our kids? No sir, workers can’t live on earth ‘n board in heaven…This is the greatest movement in existence, and,” with arms stretched out in a hallelujah gesture–“I’m only sorry I’ve got but one life to spend in this great cause.”

“I am sent here as representative from the Superior Cooperative Exchange which has a membership of forty thousand,” a blond, squarely built Finn told us, and then he described the tremendous accomplishments of this organization in the North West (I had seen many of the exchange community buildings, young people’s clubs and other co-operative activities of this organization. There is no better mass organization in the country today. The Finns don’t waste words, but how they can organize!) He went on to tell of the discontent among the iron and copper miners in this section, and the Exchange ability and readiness to work with the National Miners Union in organizing those open shop hell holes.

“I’ve been asked by many delegates to this convention,” said the young representative from the Chinese Workers Alliance of the Coast, “why the Chinese toilers stand for the nationalists taking the railroad from Soviet Russia, and my answer is this: we here are a long way from China and with the censorship and terrorism that exists there, it takes some time for reliable information to reach us in this country. But I know as sure as I stand here, that the Chinese peasants and workers will never let the war lords make war on Soviet Russia. They are fighting, and will fight to the death to defend the workers’ fatherland, and are making ready to seize power in China. Let us, here, organize and prepare to do likewise!”

Delegate after delegate took the floor. Workers from metal, shoe, electrical and steel plants, off the railroads, and from the printing, building, automobile, and many other industries. It was like a great moving picture which hour after hour took us into every industry and part of the country, showing us the lives of America’s millions of toilers, and their determination for relentless battle against American imperialism, with its speedup, wage cuts, unemployment and threatening war. Many times the movie was turned on toilers’ lives in Russia, and the contrast was sharp and clear. “Just let the capitalists dare to attack Soviet Russia, we will show them!” Many declared, “There is no doubt of what we workers in this country must do. We must follow the Russian workers’ and peasants’ example.”

Solidarity ran like an electric current from worker to worker, stretching out from the hall where we sat to all parts of the world. We saw millions of lives pouring into a common stream, generating a dynamo of invincible power, creating a machine which would rash through all the hells that capitalism can invent.

This, fellow-workers, was what Cleveland was: a genuine expression of the laboring masses of this country. It was no mere demonstration, either, but a declaration of battle, a call to the colors for organized, persistent action. And in this drive forward, the Communist Party was organized as leader.

Cleveland was American labor’s three days, in preparation for the ten days which will shake this powerful stronghold of capitalist imperialism to the earth–and its ruins we, workers, will build up the new.

III.

Binney Green, slight, fair haired, a girl striker who barely looked her fourteen years in the gingham slip she wore, spoke next. Her thin, childish voice piped across the hall, telling of the exploitation of child laborers in southern cotton mills. She ended with these words, “We mill hands down South bin mindin’ the bosses all our lives, but since th’ first of Aprl we bin lettin’ th’ bosses know the workin’ class position.”

After other talks, on special phases of the tasks facing American labor, we broke up into eighteen industrial conferences. It was in these conferences, which met for two or more long sessions, that workers of each industry came together and grappled with the specific problems facing them in their industry. And how they grappled! Past experiences and methods were ruthlessly analysed, and the future programs of organization work were thrashed out. The most detailed, practical work of the convention was done these conferences.

For workers in a few industries, mining, textiles, clothing, automobile, shoes, and marine, where new industrial unions had already been formed and were forging ahead, the discussions centered around building the new unions. In other industries, as those of printing, building and railroad, the central task was that of left wing work within the existing unions. But more of the conferences were faced with the task of organizing in as yet unorganized industries, such as those of steel, rubber, oil and chemical.

That evening, the waitress passing out coffee and sandwiches across a quick lunch counter to us, while we grabbed a hasty bite between sessions, asked “What kind of a convention are you having over there, anyway? A union convention? What’s that like–an organization like what my pop belongs to? He’s a railroad conductor.”

“Alike, but different.” And we explained. Meanwhile, she pursued her gum and gazed at us with astonishment in her pale blue eyes. “Well, I must say, I never heard such ideas before.” “Have you got a union here?” we asked.

“Naw. What do we need with a union? What cud th’ union do fer us?”

“Huh! Got all you want, I suppose. Satisfied, are you? Only nine to thirteen hours a day. And $14 a week. Huh!” Mary, my companion, grunted in disgust. Mary was a steel worker in a Cleveland plant, had organized a good shop committee there and they were issuing a shop paper. The bosses were at their wit’s end to get next to her bunch but so far they hadn’t succeeded. Everything was piece work there, and if you went at top speed all you could earn was fifteen a week. Working conditions were rotten. A regular stink hole. Workers there didn’t need to be told they needed a union!

Mary gazed at this female Henry Dubb who gazed back across the counter, and drew a long breath. Then she proceeded to do her proletarian duty. “Maybe you think this is a free country, too, do you? Well, last week I was arrested for making a speech downtown where we were holding a meeting. How’s that for a free country?”

“Arrested! My gawd. Have you been in jail?”

But Mary was hastening on to tell why workers need to organize, in order to protect their interests. Another hash slinger came over, and joined in.

“You’re right about a union, kid,” this youngster put in. “Conditions ain’t what they might be. But how’d we get all the girls to stick together? How do you start a union, anyways?”

Mary launched into a detailed explanation, and offered help, while both waitresses chewed on, keeping their eyes glued to her face. Evidently they had never come across a girl like her before. A real Bolshevik.

As we were leaving, the second waitress inquired, “Could outsiders visit your convention, maybe?”

“Sure,” Mary answered. “And what’s more, no member of the working class is an outsider at this convention. It is for people like you and me, the exploited and unorganized. Tell me when you’re off, and I’ll come for you.” And we went back to the evening session.

After the session closed, weary miners and their wives trudged, with sleeping children in their arms, to the hotel quarters arranged for them. They were looking forward to catching up a little on the sleep they missed in the night before, in their all-night travels by truck to the convention. But on arriving at their quarters, they found that two of the hotels flatly refused to admit the Negro members of the delegation, although the rooms had already been paid for. So, at eleven thirty p.m., the one hundred and fifty of them, declared a strike on these hotels and set out to find new places to sleep. A few of the white delegates, not finding other accommodations, slept out on park benches rather than use quarters in hotels which refused shelter to their colored fellow workers.

At breakfast the next morning, we sat at a table with two oil workers from Indiana. One was an old-timer, who proudly showed us his A.F. of L. card in the boilermakers’ union. “Have you ever been to an A.F. of L. convention?” he asked me.

“Sure, more than one. In fact, I’m still a member of an A.F of L. organization.”

“Well, sister, this here is different from any labor convention that I’ve been at. It’s different. I ain’t caught onto it all yet. But everybody seems to mean business.” (Righto, brother. No mere resoluting. word slinging gathering here.) “Then,” he scratched his head and squinted his eyes in an effort to express himself, “it’s a different spirit, file.”

This is how he came to be a delegate to this congress. He worked in one of the biggest oil refineries in the country. For years he had tried to get the A.F. of L. to come down and organize the plant. The men were ready. Well, first it was promises. Then it was excuses. Finally, it came to him that for some reason, the A.F. of L. wasn’t interested in organizing the oil industry. Then about three months ago he had gotten wind of a Trade Union Unity League organizer in Chicago, so he decided to go over and see him. They talked things over, and organization work was begun. A meeting of two hundred workers had chosen him and his companion to come here and make plans to organize their plant and oil industry. So here they were.

Were the workers in their plant ready for organization–they’d say! Men earning fifty and sixty cents an hour, girls getting around thirty, and all sections being speeded up like hell.

He felt hadn’t grasped all the program yet, but one thing he was sure about–the T.U.U.L. was right in standing for industrial unions, and a fighting policy. He could see now how all these years the craft form of organization had held them back. But, in the next breath he was arguing against his young companion’s statement that the women were being more exploited than the men, although they earned from one-third to one-half less, because, after all, he reasoned, they didn’t have families to support, and what they did was only woman’s work, anyway, no man would do it. “No,” the younger oil worker replied. “No man could do it. It would kill him.” And he explained why and how the women were more exploited. Meanwhile, the older man listened intently. He was an interesting figure: an old time A.F. of L.-er, skilled mechanic, hard healed and sincere, forced by his determination to serve the working class and by the logic of circumstances into the ranks of the revolutionary union movement, and trying to get his bearings there. New ideas were struggling with the old in his head, and he was sweating with the tremendous effort of thinking it through.

As I watched his starched white collar wilt and crumple, I thought of the various others like him who were at this convention, and of the thousands in local unions scattered throughout the country who had sent him here. Rank and file A.F. of L.-ers, thoroughly disgusted with its leadership and enthusiastically entering the left wing movement. Economic and social forces had swept them free from their old conservative moorings to new revolutionary ones. They were all set for militant action, but the task of acquiring a new labor outlook and understanding was almost overwhelming them. A worker can’t discard an old stem of thought which he has followed for ten or twenty years and get a new one overnight. He’s got to sweat for it. Well, this convention was surely giving chaps like our mate here a turkish bath.

It was on the second day, when the general reports by Foster, Dunne and others came up for discussion that the masses got the best opportunity to tell their story. Over eighty delegates took part in the discussion, and many more wanted the floor, so that Jack Johnstone (who, with shirt sleeves rolled up and collar loosened was wielding the gavel) found himself hard put to it, to be sure that every section of the working class had a chance to have their say.

The first to get the floor was a Negra seaman, from Philadelphia. “I’ve been fighting the bosses for forty years. For twenty years I fought ’em single-handed. I was like a dog chasing my cail. But,” he added, grinning at our laughter, “I was on my way! Then I joined the union, but the light was dark. Very dark for us colored workers. Today is the brightest day of my life. I saw the beginning of this labor fight. I want to see the end. Yesterday, when I heard what that little girl from Gastonia had to tell, I said to myself, ‘Jim, any man that won’t join the union movement now is a bum.’ I’m going back to my colleagues and tell them that they’ve signed up with the best organization that God lets th’ sun shine upon.”

“I’m a miner’s wife,” a tall, pale woman told us, “and until four. months ago I was a steel worker, too. I ain’t used to speaking in public like this, but I just want to say that we mining people know, we’ve got the toughest fight that the miners ever had in this country before us. We’re going through hell now. Starvation wages, accidents on the increase, and little or no work. We got to fight the bosses, and government troops, and the Lewis gang, too. But the miners know how to fight and so their women. And so do their kids. And you miners,” she said, pointing back to the benches where one hundred and fifty miners and their wives sat–some of them with crutches nearly, others with the sight of an eye gone, many pitmarked with pallor and coal dust which ha! eaten into the skin; all poorly but neatly dressed, and gazing at the speaker out of lean, determined faces,– “You miners got to not hold your wives back but draw ’em into the struggle more. And you women got to get more active, even than what you are.” Then, turning toward the rest of the delegates, she said, “We mining people want the other workers to know what we’re up against, and what we’re going through and that we’ll never give in. We know we can count on you backing us up, and you can always count on the miners.”

“The Cigarmakers’ local of Wheeling, West Virginia sent me here as their representative to this convention,” a big-framed, ponderous individual declared, and then he told us of the frightful conditions in the tobacco plants in their district, and how the tobacco workers, men. charter and girls, colored and white, organized themselves and got from A.F. of L. union. The international took their dues, but did nothing for them, and when the local union decided to call a strike, for better conditions, the International replied that “the office cannot see its way clear toward allowing the local union to go on strike at this time.” “Well, we struck anyway,” the speaker added, “and we’ve found out who our friends are in the labor movement, and who are our betrayers. And so my local union sent me to this convention.”

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n214-NY-nov-13-1929-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n215-NY-nov-14-1929-DW-LOC.pdf

PDF of issue 3: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1929/1929-ny/v06-n216-NY-nov-15-1929-DW-LOC.pdf