Alexei Rykov, who would soon replace Lenin as Soviet Premier, was the central figure in early Soviet economic administration as Chair of Supreme Soviet of the National Economy. Here, he responds to the challenges of the The Declaration of 46, the Left Opposition, a number of signers being prominent co-workers of Rykov’s in economic policy. In addition to historic interest of the inner-party struggle, Rykov’s report is filled with great detail on the state of the Soviet economy several years into the NEP. The end of 1923 witnessed a definite retreat in the world class struggle as the post-war revolutionary wave receded. Germany saw its third (or fourth) failed revolution in as many years, Bulgaria saw a counter-revolution and the annihilation of its mass Communist Party, and Italian Fascism consolidated its rule over one of Europe’s most combative working classes. Internal to the Soviet Union, the New Economic Policy had brought some reprieve while at the same time bringing in to sharp focus the massive tasks ahead, and therefore disagreements on how to proceed. Any hope of Lenin’s recovery at the beginning of the year was dashed, with it clear he would not return to activity, aggravating existing divisions within the leadership.

‘Soviet Economy and the Party Discussion’ by Alexei Rykov from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 16. February 29, 1924.

Address delivered by Comrade Rykov at the meeting of the Party Nuclei Bureaus and of the active Party Workers, on the 29th December 1923.

As in the discussion on democratic centralism what is really sought, is the physical exhaustion of the adversary, I step upon this platform with a half audible voice, and in an extreme state of exhaustion.

The lack of a co-speaker is bound to render my task considerably more difficult. I should like to limit my time in every possible way, so that at this meeting the Central may hear a complete criticism of its policy in the sphere of economics; I am especially anxious to deal with those parts of our resolution against which objections have been raised.

The absence of a co-speaker shows that, with regard to the essential character of the resolution with reference to the present tasks of economic policy, there do not exist any differences of opinion sufficient to cause that group of Party members who have organized themselves as an opposition in the question of democratic centralism to submit any parallel decisions to the Party. This is the more comprehensible as it is impossible to say, with reference to practical work, which of us bears the most responsibility for the actual carrying out of our economic policy during the past year. For if I, for instance, am chairman of the Supreme Political Economic Council, comrade Pyatakov is my deputy; and while comrade Kshishanovsky, who supports our views, is chairman of the State Planning Commission, comrade Pyatakov is his representative, and comrades Preobrashensky and Smirnov are members of the State Planning Commission, comrade Smirnov being at the same time, I believe, a member of the presidium of the State Planning Commission, and so forth. Thus all the leading organs who bear the responsibility for the practical execution of economic plans, share the responsibility equally between the two parties. In my opinion this should prevent the discussion on economic questions from sinking down to the level of such trifles, anecdotes and excuses, as our discussion on the inner Party situation has sunk. Another reason why I declare this is, that naturally neither I nor the Central can maintain that every necessary step has already been taken in the sphere of our economic life.

Neither I nor the Central of the Party, nor the Party as a whole, can maintain that no error whatever has been committed in the execution of our economic policy. This applies especially to comrade Sokolnikov. The discussion on the economic question and the economic question will be closely bound up with all questions of our financial policy. I must declare in advance that the Central takes the responsibility for the fundamental lines of our financial policy, but that neither the Central nor comrade Sokolnikov can take the responsibility for those deficiencies which have existed, still exist, and unfortunately will continue to exist, independently of the composition of the Central of our Party.

We must endeavor to keep the discussion on our economic policy on the level of principles, and to confine ourselves to illuminating the fundamental factors of our economic policy and our economic practice. If you examine the principles of the Central, you will see that these fall into three main parts. The first of these parts comprises the results of the activity of the Party and of the Soviet apparatus in almost every sphere of our economic practice.

The second part contains the criticism and ascertainment of this or that error which may have been allowed to creep in, and the third part refers to those practical measures whose execution we regard as indispensable for the immediate future.

Why was it necessary to give an account to the Party of those successes gained last year in the sphere of economics? In my opinion this necessity arose from the fact that an accusation was raised from out of the midst of the opposition of the Central, immediately before the last plenary session, to the effect that the policy pursued by the Central had brought the country to the verge of ruin. As you are aware, the last plenary session of the Central and of the Central Control Commission resolved not to send out the documents referring to the differences of opinion within the Central. It is true that the addresses on the economic policy are filled with a large number of figures, and are thus bound to be tiresome to a certain extent, but I consider it incumbent upon me to make mention of the accusation thus brought up against the policy of the Central.

I believe, and I hope to be able to prove, that precisely the contrary of this accusation is true, and that there can be no talk whatever of the Party or the Central having brought the country to the verge of ruin, but that on the contrary, the results of the past year, in every sphere of our economics were more successful by far than those attained in the previous years. I therefore proceed to an analysis of the various branches of our economics.

The Party Central, in its resolution, accords the first place to the question of the situation of the peasantry and of agriculture, and to the attitude adopted by the workers towards the peasants. It was not by accident that we did this, but intentionally, as we are of the opinion that there is something not quite in order on this particular point, the relations between workers and peasantry. The passages quoted from the resolution passed by the XII Party conference, referring to industry, and incorporated in the introductory part of our resolution, dealing with the present tasks of economic policy, are not from the pen of the author of the resolution passed by the last Party Congress, but were incorporated in the resolution of the XII Party Congress by the CC, against the will of the author. The opponents of these quotations desired to prove that, since comrade Trotzky had not reported on the situation of economics in general at the Party Congress, but on the situation of industry, it was not necessary to deal in this resolution in such detail with the attitude adopted towards agriculture, and proposed that this be substituted by the addressing of a special appeal to the peasantry, in the name of the Party Congress, expressing the good will with which the communists are filled towards the peasants. We declared ourselves to be not in agreement with this, and emphasized that the policy pursued by the working class with reference to the organization of industry can only be crowned with success when the interests of the peasantry and of the agricultural market receive fullest consideration in the daily work performed by industry. This question was finally discussed at the plenary session of the Central, which declared itself in our favor, and against the opposition.

If we examine the actual practice of our economic organs during the past year, we see that the interests of the peasantry were taken too little into consideration, and that, if any reproach can be made against the Party Central at the present time, it is that though it has proved fully equal to its task in the industrial question, and in suitably adapting comrade Trotzky’s draft resolution, it has not taken sufficient care that the alteration provided for in the peasant question by comrade Trotzky’s resolution should be fully and completely realized in the activity of all our economic organs. Hence it comes that is the first time, so far as I can remember, that the resolution of the Party Central on our economic policy places the question of the relations to the peasantry, and of the situation of agriculture, in the first place, before the industrial and workers’ question. This has been done because it was precisely on this point that we made a false step last year, and because a considerable portion of the economic difficulties and crises, with which we have had to deal during the last two months, have come about through an incorrect estimation of the significance of the lines laid down by the Party in this direction.

I now pass on to statistical statements on the situation in the separate branches of our economics. My sole purpose in adducing these is to show that at the present time there is no thought whatever of ruin or the “verge of ruin” for the Party and for the working class, and that we can look with considerable pride upon the work accomplished by the Party last year. Has the situation of the peasantry improved or worsened during the course of the past year? If we turn to the statements on the area of land cultivated, the total production, the amount of wares possessed by the peasantry–that is, to that total of products placed by the peasantry upon the market, we shall see that the past year brought an increased improvement in the situation of the agricultural economics.

In comparison with last year, the area sown has increased by 18,8%–from 51,4 million desyatines to 61,2 million desyatines, and has reached 71% of the area sown before the war (within the confines of the present area of the SSSR.). For the coming year the position has worsened to a certain extent; this is a result of the poor autumn-sown crops, the loss amounting according to the returns issued by the Central Statistic Administration to 4% of the autumn-sown area of the part year–a loss principally due to unfavorable climatic conditions. There is however, reason to assume that this loss will be compensated by the spring–sown crops.

With regard to the total production of agriculture, this has increased but slightly, owing to the lessened yield of the crops. The State Planning Commission states the total production to be something over 3000 million poods, the Central Statistical Administration gives the figure at 2794 million poods (as against 2790 million poods, as per statement made by the Central Statistical Administration last year). You are aware that the taxes in kind have assumed an easier form, the possibility being given to the peasantry to substitute this tax by a money tax, and this tax and a number of other taxes being combined into one single agricultural tax. The enormous extent to which the peasants have availed themselves of the possibility of substituting the tax in kind by the money tax, may be seen from the fact that out of the 341,5 million poods of rye units raised by taxation up till 1. December–amounting to more than 60% of the taxation plan–only 77,4 million poods were paid in kind, whilst the remainder was paid in money or corn loan; in the year 1921/22, on the other hand, 400 million poods (in round numbers) of rye units were raised as tax in kind. The fear expressed last year, that the peasants would find it difficult to pass from taxes in kind to money taxes, has proved to be entirely unfounded.

As result of the general revival of agriculture, and in part as a result of the possibility afforded the peasant of paying the taxes in money, the amount of goods possessed by the peasant, that is, the total amount of products placed by him on the market, and estimated by comrade Brukhanov at 500 to 550 million poods for the grain production alone, has increased.

This circumstance confronts our trading and grain procuring organisations with the full extent of their task of procuring enormous quantities of grain for the market–both for inland requirements and for export abroad–a task of extraordinary importance, for it includes to a considerable extent the question of a market for the products of our industry. A program for procuring 270 million poods has been worked out for our grain distributing organizations (this includes not only export, but the covering of the requirements of the non-agricultural gouvernements, and of gouvernements suffering from failure of crops, in accordance with the plan for the distribution of grain supplies).

According to statements which I have received from the special committee for the procuring of grain, appointed by the Council for Labour and Defence, up to the 20th December grain had been bought up to the value of 163,9 million poods. (Last year only 54 million poods were bought). Up to 24. December, 93,5 million poods of bread and fodder grain had been sold to foreign countries, and 81,2 million poods of this quantity had been already despatched abroad.

Whilst I am dealing with agriculture, I must at least touch briefly upon that part of it which is of most immediate interest to the workers, not as corn consumers, but as producers of goods, as workers in the factories and industrial works; I mean the agricultural raw materials for our factories and industrial works, and the considerable improvement of the situation in this sphere, thanks to the extension of the area devoted to the cultivation of plants for technical purposes. If we take for instance the area under flax cultivation–in the flax growing regions–we see that this was only 424,000 desyatines in the year 1920, 460,000 desyatines in 1921, 498,000 in 1922, and 512,000 desyatines in 1923, so that this cultivation has increased by almost 25% in comparison with the year 1920.

One of the factors which have stimulated the peasants to develop the cultivation of technical plants, is the considerable increase in price of agricultural raw materials for our industry, owing to the rapidly increasing demand for these articles both within our Union and abroad.

Let us take the prices for linen, wool, and skins, and we shall see that last year experienced an extensive rise in prices for all these goods.

According to the statements issued by the Committee for Home Trade, the price of linen, fourth group, rose from 3,20 gold roubles in January 1923 to 6,75 gold roubles in October 1923, that is, by 110%. The price of linen, fifth group, rose from 2,95 gold roubles in January 1923 to 6,72 gold roubles in October 1923, that is, by 127%. During the same period the price of linen, sixth group, rose from 1,65 gold roubles to 5,28 gold roubles, about 220%.

In comparison with pre-war prices, the September price for linen was 145% for the fourth group, 132% for the fifth group, and 111% for the sixth group.

These groups in fact comprise 95% of the Russian linen production.

Sole leather rose from 38 roubles 31 kopeks (goods roubles) for the pood in October 1922, to 61 roubles 66 kopeks in October 1923. For raw wool the corresponding figures are 2 roubles 88 kopeks for the pood and 10 roubles 32 kopeks, signifying a three-and-a-half times rise in price.

I must also make mention of the great successes obtained last year towards the restoration of our cotton production–cotton is one of the most important raw materials of our industry. In the year 1920 the production of cotton fibre in Russia amounted to 733,000 poods, and in the year 1923 to 2.600.000 poods, a more than threefold increase in comparison with the year 1922. The program for the year 1924. provides for an increase of our cotton production up to 6 and 7 million poods. The successes obtained in the development of our cotton production do not, however, keep pace with the requirements of our cotton industry, whose activity is calculated for the year 1923 on the working up of about 6 million poods of cotton, and this year we were already obliged to resort to importing expensive foreign cotton, the price of which has risen almost threefold in comparison with pre-war times.

The price for an English pound of cotton was as follows, calculated in pence: 1913 7,27, 1920 11,89, 1922 15,2, 1923 20,03. Before the war the price of Russian cotton varied between 14 and 16 roubles for the pood, whilst the statements now lying before me show that the state trading office (Gostorg) has offered a price of 44 roubles free Murmansk for American cotton equal in quality to Russian.

At the present time the maximum price for Russian cotton has been fixed at 25 roubles.

The present high price for cotton goods is mainly caused by the rise in the price of cotton, and until our cotton production can be made to meet the requirements of our factories, rendering us independent of the import of expensive foreign cotton, the further development of our cotton production must remain one of the most important tasks of our economic activity.

During the past year the peasantry was required to pay taxes to a considerable degree in money form in accordance with the instructions of the Party, and we are already able to judge that the single agricultural tax is not bringing us all which we expected from it. The reasons for this are as follows: the mixed systems of collecting the single agricultural tax, the system of two currencies (chervonetz and Soviet money); the rapid depreciation of the Soviet currency, the fluctuations and variations of the grain prices; all this has greatly increased the difficulties attendant on organizing such a technic for the collecting of the agricultural tax, by which the state shall suffer no loss, and no incorrectness will be caused in separate cases in the collection of the tax. With respect to the peasantry, our tasks for the coming year are thus chiefly: 1. Substitution of almost the whole of the single agricultural tax by a single money tax. 2. Emancipation of the peasantry from all and every supplementary collection, such as are now made.

The third and most fundamental reform must consist of an improved currency. At present we have a double currency, a Soviet currency which depreciates in value from day to day and is mainly received by the workers and especially the peasants, and a chervonetz currency, which rises steadily in value, and moves in large money units in commercial and industrial traffic, only coming to a very small extent into the hands of the workers and peasants. The sinking Soviet currency must be substituted by a stable value circulating medium. At the present time the chervonetz circulates principally in the cities. It is true the workers have suffered through the depreciation of the Soviet currency, but generally speaking, the peasantry had, so to speak, the monopoly of the results of the depreciation. Among the peasantry there has practically been no other currency, and they have not had the advantages possessed by the workers, who have at least received this Soviet currency in accordance with some goods or chervonetz index figure. This fundamental reform with reference to agriculture and the peasantry must be carried through in the course of the coming year. I shall here not touch upon the large number of other proposals which have been accepted and con firmed by the Central of the Russian CP, and which have not given rise to any doubts; these proposals refer to the organization of agricultural credits and agricultural co-operatives, and to the better adaptation of the whole of the policy pursued by our Party in the country to the various strata existing among the peasantry. Although the statistics furnished by the Central Statistical Administration show that the new economic policy and the free circulation of goods have not yet led to any sharp division of the peasantry into rich and poor, still there is no doubt whatever but that the new economic policy and the free circulation of goods have, on the whole, provided sufficient prerequisites for permitting this formation of strata to proceed more rapidly than has ever been the case since the October revolution. Thus the whole of our policy with regard to the peasantry must be brought in every particular into strictest accord with the necessity of lending support to the poor and medium peasants, and must fight against village usury and against the growth of a village bourgeoisie.

I now pass on to big industry. This question is of the more interest in that the present period coincides with a crisis in our big industry. Should a general characterization of the relations between big industry and other branches of economics be given, it must be declared: 1. that our big industry has grown to a greater extent during the past year than in any previous year, and 2. that it has grown more in proportion than agriculture and small industry. In one of the discussions, contradictions in the resolution of the Party Central were pointed out, which were said to consist in our having declared in one place that the speed of industrial restoration was more rapid last year than the speed of restoration of agriculture, whilst in another place we speak of a disparity between the rising peasant economics and industry. The misunderstanding here lies in the fact that in the one case the standard taken is that attained by agriculture and industry in comparison to pre-war times; in agriculture this standard is higher, as a result of the fact that agriculture, thanks to its extensive character, was not exposed to such severe devastations during the war and revolution as was the case with big industry, and thus kept up a much higher level than industry, even in unfavorable years, in comparison with pre-war conditions.

At the present time, agriculture has reached about 70 to 75% of its pre-war extent, whilst industry, despite its considerable development during the course of the past year, has only attained (approximately) 35% of its pre-war standard.

But if we take the speed of development of industry and agriculture last year, we cannot fail to observe that in the year 1922, industry showed an incomparably more energetic uplift than in the year 1921, and showed a considerably greater increase of production than agriculture.

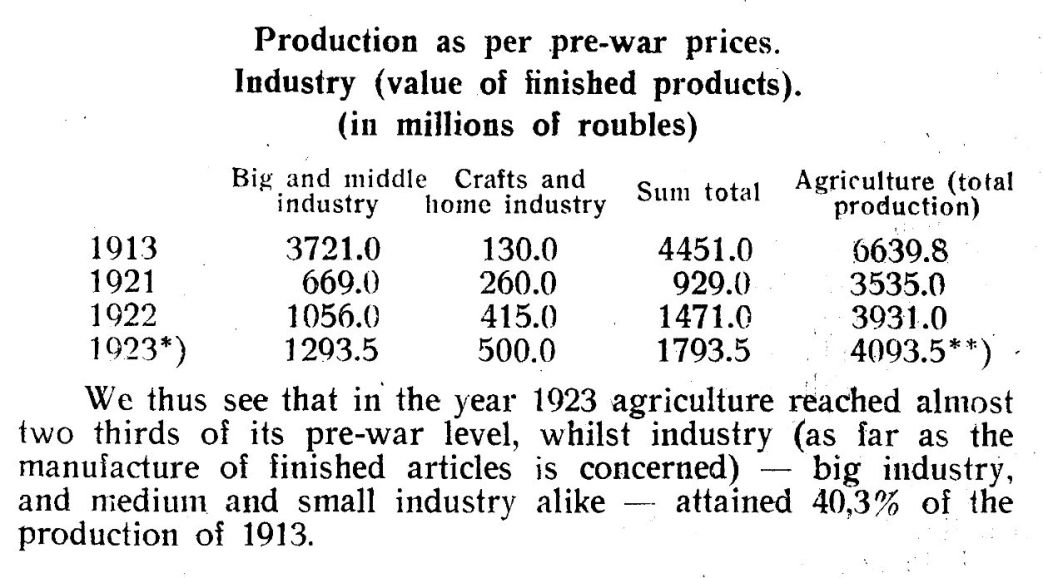

In order to characterize the situation generally, I here adduce an extended form of the table submitted to the 12. Party Congress by comrade Trotzky; this furnishes a graphic survey of the position of big industry, small industry and agriculture, alike in comparison with pre-war standards and with reference to the speed of development during the last three years.

Thie table is drawn up not in terms of years of economic operation, but in years according to the calendar; the Central Statistical Administration has in addition to this now at its disposal more complete statements than those upon which comrade Trotzky based his table, it has made some alterations in the figures of this table.

*) The production for the year 1923 is roughly estimated. **) Agricultural production is here stated without consideration for possible statistical omissions, and without including forestry and cotton production, or some few other small branches of agricultural production.

We thus see that in the year 1923 agriculture reached almost two thirds of its pre-war level, whilst industry (as far as the manufacture of finished articles is concerned) big industry, and medium and small industry alike attained 40,3% of the production of 1913.

If we now turn to the note of development in agriculture and in industry during the past year, we see that whilst agriculture has only increased its total production by 4% in comparison with 1922, industry as a whole can show an increase of 21,8%. And if we compare the development of big and little industry from 1922 till 1923, we shall find that whilst big industry has increased its production of finished articles by 22,04% in comparison with 1922, small industry shows an increase of 20% during the same period; the figures thus given on the growth of big industry are the minimum ones; according to statements which I have received from the State Planning Commission, the total production of big industry increased last year by no less that 35%. According to this table, the increase of production during the past year is to be statistically expressed as follows (in millions or pre-war roubles):

For big and medium industry…237,3

For crafts and home industry…85,0

For the whole of industry…322,3

For agriculture…163,5

Which branches of industry show the greatest increase? You know that the question of the order in which the various branches of industry were to be reconstituted formed a subject of lively discussion even during the period of war communism, and that there were considerable differences of opinion as to the question of how, and by what means, the beginning should be made. These discussions and divergence of ideas are for me, merely aspects of that question of the over-estimation of the importance of drawing up plans. For at that time it was thought possible to form a plan and to reconstitute this or that factory, this or that branch of industry, in accordance with this plan. You are aware that most of these plans came to nothing, they were not successful. With the transition to the new economic policy, the whole of our industry came under the control of the markets, of the possibilities of selling, and functions under the conditions of traffic in goods and money. Thus the technical or abstract plan which we worked out in the war period of our history, is now subjected to cardinal alterations through the exigencies of the market. Industry has to work for the market. If you examine the statistical statements, you will see that the effect of the market is shown by the gigantic increase in articles of mass consumption; for industry, striving to satisfy the demand, has developed its production parallel with this demand, and has obtained from the market the means for this development. The main effect of the state planning principle has been felt in the fact that we furnished from our budget the most extensive possible means for the restoration of the fuel industry, for the restoration of our means of transport, and for the electrification of the country, and made it our endeavor, not only to maintain the corresponding proportion of light industry, but to create the prerequisites for the further development of industry. The figures which I shall here adduce will fully confirm this. I should like to make one more observation. There occur to me the documents sent to the Party Central. These stated that: in the first place, we have brought the country to the verge of ruin; in the second place, the successes obtained in various branches of our economics have not been attained thanks to the CC, but in spite of the activity of the CC. With regard to this “in spite of” I must therefore observe that even the growth of light industry is not to be regarded as a spontaneous growth under the influence of the market, without any participation of the planning principle.

The plans of production for the whole of our industry and its separate branches have been discussed and confirmed by the Supreme Political Economic Council.

Thus, for instance, the exact amount of cotton required for the textile industry was ascertained. Credits for the purchase of cotton and other raw materials abroad were decided upon. Light industry, however, received no financial support from the state, its production has been distributed by free sale and purchase, and with respect to prices, the role played by the planning state organs has been confined solely to the fixing of maximum wholesale prices for a very limited number of goods.

For heavy industry not only the production is planned, but also the distribution and the prices.

I do not mean by this that all these plans have been good, for some of them have been unsuccessful, and the experience of the past year shows the necessity of intensifying planning work with regard to the study of the market, the fixing of prices, and the granting of credit. I shall supplement the general table which I have adduced on the growth of big and small industry, and of agriculture, with certain statements taken from the most important branches of our industry.

The cotton industry, whose production was estimated at something more than 39 million pre-war roubles in the year 1920, increased its production to 170 millions in the year 1922 till 1923, that is, more than fourfold; the whole textile industry, if we take the production of the year 1920 at 100%, increased its production to 323,9% by the year 1922/23, and as compared with pre-war production (1912) it has attained 39,9%. The chemical industry, taken collectively, has risen from 18% of the pre-war production (1912) in the year 1920 to 46% in the year 1922/23. Other branches of light industry have also grown more or less considerably during past working year.

Heavy industry is of leading importance for the reconstitution of economics, and in heavy industry itself the most important branch is that of fuel production. During the past year we have not only been relieved of the struggle against shortage of fuel, but have even had difficulty in selling all our fuel, and have considerably lessened our purchases of coal abroad.

The total production of coal (in thousands of pre-war roubles) during the past year, in all districts, is estimated at 69.273, making about 160% as compared with the year 1920. The Donetz basin, the extraordinary importance of which for the whole economic life of the country has caused the question of its general support, development, and growth to be placed on the agenda of almost every Party Congress, and at the conferences of the All Russian Central Executive Committee, has been able to record a total production of 493,7 million poods in the year 1922/1923, thus increasing its production by 83% in com- parison with the year 1920, and attaining almost 50% of pre-war production.

In comparison with the year 1920, naphta production has increased more than 30%, and reached 56,6% of pre-war production (1922) by last year; the increase of production in the different districts may be seen from the following statements:

In Baku, the naphta production has increased from 175 million poods in the year 1920 to 212,8 in the year 1922/23, signifying an increased output of 22%; in Grosny the corresponding figures are 53 millions and 92 millions, equal to an increased output of 74%. If we take coal and naphta production together, we see that their production, expressed in pre-war roubles, amounted to almost 200 million roubles in the year 1922/23 (statement issued by the Supreme Political Economic Council), or, in other words, about 50% of the pre-war production.

Thanks to the successes obtained in the naphta and coal industries, we have now a secure basis for the fuel supplies of the country.

Precisely in the same way as we emerged successfully from the “bread crisis”, we may now consider that we have overcome the fuel crisis. In our economic construction this is a very important gain. I remember very well that when we, when working in collaboration with Vladimir Ilyitch in the Council for Labour and Defence of Country, were obliged to expend an enormous amount of work in order to assure a supply of bread for the workers, and to prevent the railways from becoming paralysed for lack of fuel. For hours we discussed the question of some gouvernement forestry committee to supply some railway station with wood. In this year we are not compelled to occupy ourselves with this question in such a form. If you take the fundamental figures referring to the supply of fuel for the railways, you will find that whilst in January, 1921 the railways had a stock of fuel sufficing for 11 days, I can remember times, during the period when we worked together with Vladimir Ilyitch, when there was only fuel for two days, and complete stagnation of the railways appeared inevitable on October 1st. 1921, we had reserves for 26 days, on 1. October 1922 for 39 days, and on 1. October 1923 for 70 days.

If the fundamental elements of fuel economics are surveyed in accordance with the statements given on the total fuel transport of the railways for the past year, and compared with the analogous statements for the years 1920 and 1921, we arrive at the result that in the years 1920/21 wood formed 75% of the total fuel transport, naphta 11%, and coal 16%. If we take these statements as the basis for judging the balance of the mutual relations of the various elements composing our fuel material, we shall find that wood forms about three quarters of our fuel balance, only a trifle more than one quarter falling to mineral fuel. In the years 1922/23 the corresponding figures are as follows: for wood 57%, for naphta 14%, for coal 29%; consequently, the mineral fuel coal and naphta is now 43% (instead of 27% in the year 1920-21). In other words: our fuel balance, of which only a quarter consisted of mineral productions in the year 1920/1921, has so developed that mineral fuel now forms almost one half. In this respect a very great improvement of economic conditions has been attained.

Matters are not so favorable with respect to the reconstruction of the metal industry. The principles laid down by the Central contain one special passage in which we declare that an extraordinary degree of attention is to be accorded to the restoration of the metal industry; up to now the lack of fuel and the unfavorable transport conditions, as also the necessity of expending gigantic sums on the restoration of fuel production and of means of transport, have formed enormous obstacles to the development of the metal industry, but now matters have so greatly improved with regard to fuel and transport that the question must be raised as to how we shall best expend the greater part of those sums, hitherto spent for fuel and transport, for the reconstruction of the metal industry in the coming budget year. The fate of the metal industry is bound up with the fate of the main troop of the working class, the metal workers, whose superior organization and class consciousness render them the leading stratum in the working class.

If the data on the metal industry in the year 1922/23 be compared with those for 1920, a considerable success may be recorded. Thus we have more than doubled our production of cast iron during this time (7.025,000 in the year 1920 and 18,360,000 in the year 1922/23). The production of the Martin’s furnaces has been more than tripled, that of rolled metal more than doubled.

The whole metal industry, including the working up of metal, attained last year an average of 20% of pre-war production, if we value its production at pre-war prices (the working up of metal forming the greater part).

But if the absolute figures be taken with regard to cast iron, Martin’s furnaces, and rolled metal, and compared with those of pre-war production, it must be admitted that the results attained in the sphere of metallurgy (especially in cast iron production) are entirely insufficient, and show that we are only just beginning the restoration of the metal framework of our industry; thus cast iron production last year was only about 7,9% in comparison with the year 1912, the production of the Martin’s furnaces 14,8%, and the rolled metal production 13,7%.

The reconstruction of the metal industry is most closely bound up with the state orders, for the mass market even in former times, did not consume more than 24% of the production of the metal industry. Our metal works will only be able to develop if the state can give large orders. The restoration of our metal industry is still tremendously hindered by the error which we committed in the year 1920, when gigantic orders for railway material and locomotives were sent abroad. These orders have now been reduced to the extent permitted by the agreements, but they have none the less demanded the expenditure of huge sums, and we are still importing goods which we could very well produce in our industrial works. These orders were given at a time when I was at the head of the Supreme Political Economic Council, and comrade Trotzky at the head of the People’s Commissariat for Traffic. Now we have on the one hand a superfluity of locomotives on the railways, and on the other a lack of orders for our engine manufactures. The small number of engines now being produced by our works will not be required by us for five years, and we are having them made in order to occupy our largest works in Kolomna, Sormovo, and in part the Putilow works. Should we deprive these works entirely of orders, it would be extraordinarily difficult to reestablish locomotive building after the lapse of five to ten years. Whatever opinion may be held on concentration, a concentration carried to such lengths that a large part of the greatest industrial works employing metal workers would be closed, is no longer possible, not merely for economic, but for political reasons. The decision of the 12. Party Conference, on the question of concentration, was as follows:

“The means of escape from the present situation lie in a radical concentration of production (these words are in italics in the original), in the works possessing the best technical equipment and the most favorable geographical position. The various secondary and insignificant objections raised against this, however important they may be in themselves, must retire into the background in the face of the fundamental economic task involved in the provision of state enterprises with the necessary working capital, the reduction of initial costs, the extension of markets, and the winning of profits.”

Many comrades have begun to regard the preservation of the fundamental groups in the working class as being among the reasons of a secondary order.

It is for this reason that the resolution passed by the Party Central as complementary to the resolution accepted by the 12. Party Congress on concentration, states that concentration is indispensable, but that the necessity of preserving the fundamental groups in the working class must be taken into account. This applies especially to the metal workers.

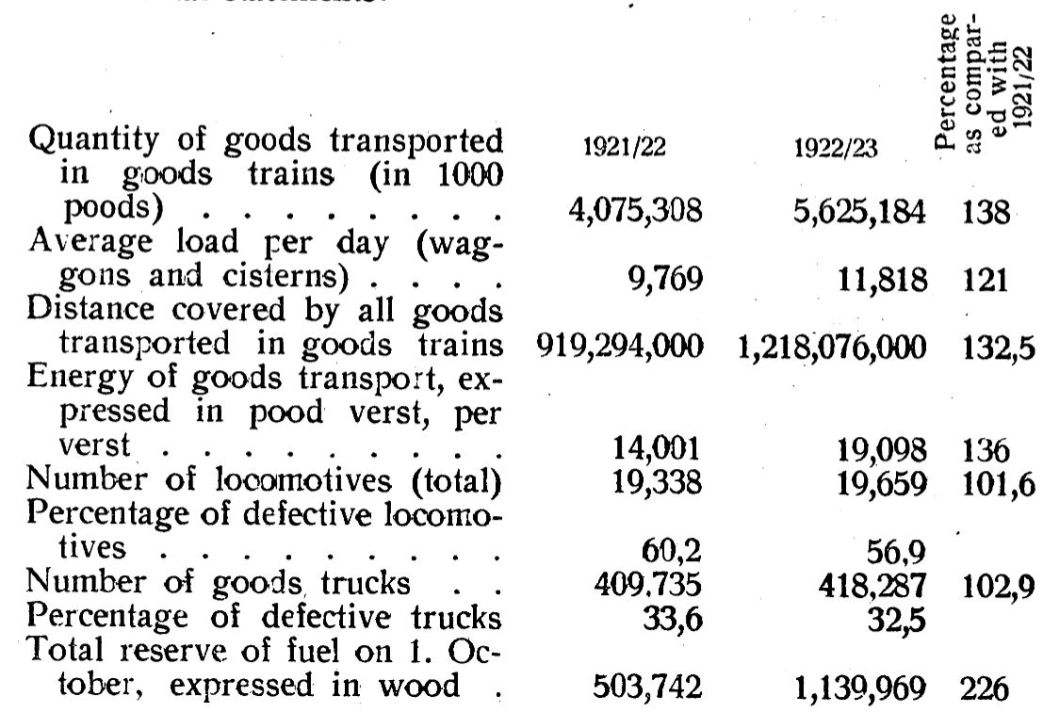

The growth of industry, of which I have spoken, is expressed in the revival of transport and commercial intercourse.

The transport conditions are characterized by the following fundamental statements:

At the 12. Party Congress comrade Trotzky quoted my preface to comrade Khalatov’s pamphlet. In this preface to comrade Khalatov’s pamphlet I pointed out that the first year of the new economic policy had witnessed a loss to industry, and that our fundamental branches of industry must be rendered free of deficit, or somewhere near it, in the course of the coming year. With respect to transport, considerable success is to be reported. If we consider the past year only, we see that during the first quarter of the year the revenues amounted to 52 millions, in the second quarter to 100 millions, in the third quarter to 110 millions, and in the fourth quarter to 116 millions. (Statements issued by the People’s Commissariat for Finance.)

Transport is still being carried on at a loss, but the deficit is being rapidly reduced. In the year 1922/23, transport was subsidized to the extent of 115 million roubles, whilst in this year negotiations are being conducted with the People’s Commissariat for Traffic with reference to a sum of 40 to 80 million roubles; that is the amount required from the state for the support of transport has been reduced to at least half that of last year, although this subsidy covers the costs for the harbour constructions, river protection, etc., expenditure having nothing in common with the railways. If we take the railways alone, these will be working almost without a deficiency next year.

I have already pointed out that we have encountered a large number of political difficulties through the concentration. When solving these difficulties, we have given the political motive the preference over the economic in the case of the Putilov and Briansk works and have not closed these down.

This does not, however mean that the directions issued by the Party Congress with regard to the concentration are not to be executed. Concentration is something which cannot be carried out in one or two weeks. To close the works, to place the workers in new positions, to find accommodation for them there, and to set production going again in another place, is a task requiring a long period, a number of months. As a result of the decisions made by the presidium of the Supreme Political Economic Council during the course of the last six or seven months on the subject of concentration in industry, the present calculations of the Supreme Political Economic Council enable us to record considerable success with respect to the improvement of various branches of productive activity. First of all comes the increase in the numbers employed by the undertakings. Here I shall confine myself to a few examples: Before the concentration of the cotton industry, the enterprises concerned were occupied up to 46,7% of their capacity; after the concentration up to 59,2%. The corresponding figures, before and after the concentration in the linen industry, were 61,92% and 81%; in the wool industry 66 and 75-100%; in the leather industry 60,5 and 90%; in the Petrograd Machine Trust 12 and 50%; and in the state cast iron works 30 and 87-96%. I could continue these examples. In connection with the question of price, I personally, as also a number of other comrades in their reports, have exercised a justifiable criticism on the communists sent to work in the trade and economic organs. We criticize them from the viewpoint of rise in prices and of the amount of working expenses. In this present meeting I must make certain alterations in the exposition given by me on a previous occasion, the more so that a number of Party nuclei have misinterpreted this exposition. I reported on the question of the crisis. And now, when discussing the question of the crisis, I shall point out a number of defects which have to be recognized and overcome in the organization of our economic life.

But I must, however, observe at the same time, that during the course of this year our economists have performed extensive work with regard to the organization of industry, its development, and the security of its uninterrupted continuance. If we regard the line of development of our industry in the past year, we see that it has developed steadily and without oscillation from month to month, for the first time in the history of our industry. This is a gigantic success for the planning principle, and for the activity of our economists. I can well recollect that at one time workers had to be dismissed from the works, and then engaged again, when shortage of fuel and raw materials forced us to close this or that undertaking for some weeks or months.

Great success has also been obtained by our economists in the sphere of the organization of the activity of the undertakings. I have before me a comprehensive table showing what was accomplished last year in the sphere of saving of fuel, the reduction of the number of auxiliary workers in comparison to the number of trained workers, and with regard to the greater saving of raw materials, etc. I shall give a few figures: Up to March 1923 the standard for the manufacture of cotton fabric from a pood of raw material was 85%, in July 87% and in October 89%; in the leather industry 1,92 pood of raw material was required for the production of one pood of sole leather up till the end of 1922, and in the year 1923 (according to the calculation of the leather syndicate) 1,89 pood was required; in the sugar industry, one Berkovetz of beetroots yielded 65 pounds of sugar before the war, 58 pounds in 1922, and 62,5 pounds in 1923 (according to budget calculation); that is, the standard is now but slightly below the prewar one. With respect to saving of fuel, the calculations made by the state cast iron works show that in the year 1922/23 the production of one pood of sheet iron required 4,2 pood of fuel, and in the year 1923/24 (according to the Program) 3,5 pood; the corresponding figures are 4 and 3,3 for the Malzev district, and 4,6 and 4,4 for the State Industry of colored Metals.

With reference to the reduction in the number of auxiliary workers as compared with the trained workers, the comparison made by the State Industry of Colored Metals shows a reduction of 24,4% as compared with the beginning of the year 1922/23, and of 25% in the “Red October” works; the number of auxiliary workers employed by the rubber trust, at the beginning of 1922/23, as compared to skilled workers, was 150% at the end of last year it was 66%.

The increased productivity of the workers must be emphasized. The statements of the State Planning Commission show the productivity of a worker (total production), expressed in prewar roubles, to have been 548 roubles for the year 1920; this figure had already risen to 1292 roubles by the year 1922/23, more than 60% in comparison with prewar times.

All this implies that there is a certain degree of reduction in the initial costs of production. This reduction amounts to 15% for the “Chemical and Coal Industry”, 12 to 21% for machine building, and 7% for the rubber trust.

I am, however, far from wishing to say that we have already accomplished everything towards an elementary soundness in our production–the concentration of the activity of industry in the best adapted undertakings, the reduction of the number of unskilled labourers, lessening of working expenses, etc. It must rather be admitted that we are merely on the lowest rang of the ladder, and have taken the first steps in the enormous work which absolutely must be done. The cheapening of production as a result, of concentration, the increased working productivity, and the improvement of the organization of working processes, which I have shown in the above figures, are important symptoms of the convalescence of our industry. But the success which we have so far gained is still altogether inadequate in comparison with the tasks with which we are confronted.

As a result of the campaign which we have been carrying on, and shall continue to carry on, for reductions in prices, a large number of cases have occurred, especially in the provinces, in which the economic apparatus of the Party has been subjected to exaggerated criticism. This exaggeration has reached such a point, that I have been informed of cases in which the candidatures of comrades working in trusts and syndicates have been rejected in the Party organizations, because the trusts and syndicates had forced the prices upwards and brought about the crisis. This is the greatest injustice. To be sure they made mistakes when fixing the prices, but it is none the less the result of their efforts that industry has been able to record such gigantic successes during the past year. Criticism of errors committed must be kept separate from criticism of individual persons. It is not possible for us to find other economic functionaries on such a scale, and with such extensive experience, within any short space of time.

The task before us does not consist of “shaking up” the whole group of economists, even though they have committed grave errors, nor of depriving them of support in a work of unexampled difficulty and responsibility, but in eliminating the errors, in learning from the errors, and in increasing our endeavors towards improved economic activity and careful individual selection of the economists. It is in no case permissible that communists economists be regarded by anyone as Party members of a secondary degree.

It must also be taken into consideration that in the crisis (“scissors”) we see not only the effects of the errors committed by the economists, but at the same time the weakness of the organs upon which the duty of regulating economics falls.

Industrial questions are of tremendous importance for our Party, for the growth and strength of the working class is dependent on the growth of industry. In a country in which a worker party is in power, in a country where the working class is the unshakeable support of the ruling power, in such a country the fate of our Party is most closely bound up with the question of industry, and with the questions concerning the position and growth of the working class.

According to the statements issued by the Supreme Political Economic Council, and dealing with approximately 75% of the whole of big industry (excluding transport, political economy, wood working industry, a part of the syndicate industry, a part of the chemical industry, and a part of the food industry), the number of workers increased last year from 887,548 in October 1922 to 1,100,804, that is, by 25%. The whole of the three most important branches of industry–the metal industry, mining industry, and textile industry–had a considerable increase in the number of workers employed. Thus the number of workers in the mining and metal industries increased by more than 10%, in the cotton industry by more than 45%.

These figures appear to imply a certain contradiction to the growth of unemployment, a growth very apparent in a large number of towns, and bringing the number of unemployed to the high figure of about a million. Here we may observe a phenomenon hitherto unheard of. The number of workers employed is increasing, and at the same time the number of the unemployed. You will remember that the greatest danger attending the last period of war communism was the danger of the disintegration of the working class. The skilled workers left the period of war communism, comrade Sosnovsky and a number of laws binding the workers to their places of work. During the period of war communism, comrade Sossovsky and a number of other comrades devoted many columns of our press to the discussion of plans as to the compulsory transfer of workers from one place to another. Such plans were based on the shortage of working power caused by the flight of the workers from the cities into the villages, where they could live better and more comfortably. At the present juncture, the movement is in the opposite direction. The improvement in the position of the workers, the improved conditions of living in the cities, the solution of the food supply question, etc., are now bringing about an influx of labour power from the country into the towns, and the essential question of unemployment lies in the fact that the growth of our industry is not proceeding at quite so rapid a rate as that of the return of the workers to the cities. The increase in the number of unemployed is naturally most dangerous; but this danger is lessened by the fact that a large percentage of unemployed are unskilled workers and Soviet employees. If we thus classify the total number of unemployed in Moscow and Petrograd according to the chief professions, we get the following: for Moscow, 1. December, the number of unemployed comprised 20% industrial workers, 44,7% members of intellectual professions (as a result of the reduction of the Soviet apparatus), 28% unskilled workers. For Petrograd the corresponding figures are: 22, 35, and 31%. Approximately the same proportions apply to the whole of the rest of Russia. The statements issued by the People’s Commissariat for Labour thus show that in November, the unemployed consisted of 24% industrial workers, 38% intellectual professions, and 26% unskilled workers. Thus the main mass of the unemployed are unskilled workers, that is, mainly recruits from the country, and members of the intellectual strata.

Although our revenues from, the insurance contributions are increasing, and the insurance capital is growing, we have still at the present time no means enabling us to undertake the task of greatly aiding the whole mass of unemployed. Therefore the conclusion drawn by the Party Central is that, out of the whole mass of unemployed, those first to be accorded consideration must be the industrial workers, the workers connected with the factories and industrial works, who are capable of being utilized for the further development of industry. The chief means used in the struggle against unemployment must of course be the further development of our industry.

The increase of wages for the whole of last year was as follows, for all branches of industry:

According to the statements of the economists, working wages have risen by 87%, according to the statements of the trades unionists by 63%. Among the metal workers, wages rose by 33,8% between January and December of this year. With reference to wages the Party Central issued special instructions to the effect that categories of workers who had remained behind with respect to wages should be brought nearer to the general level. First among these the metal and transport workers must be named. Among the metal workers, wages were already 17,9% above the average level in December, whilst in January they were still about the average level or 3% above it. I have not strictly checked statistical statements at my disposal on the wages received by the railwaymen; but the provisional statements which I have received from the All Russian Central Trade Union Council give the rise in wages of railwaymen as being 50 to 60% between January and October of this year, reaching 13 to 14 goods roubles by October 1923. For the future, the gradual rise of wages is to be striven for in agreement with the general improvement of our economics and the growth of labour productivity.

This is the state of affairs with reference to agriculture, industry, and wages. Despite a considerable number of successes in all these spheres, we have been suffering from symptoms of crisis since the beginning of the summer, and these were not at first accorded sufficient attention by some of our functionaries.

When I tell you that these symptoms are more dangerous than those which appeared before, I do not mean that they are leading to any reduction of production or to a worsening of the position of the working class not a single factory has been closed, and working wages are rising now as before. This can naturally only be the case under the conditions determined by the rule of a workers’ and peasants’ power. But this crisis is dangerous, because it has revealed great defects in the fundamentals of the present economic relations between town and country.

At one time we had partial crises in the matter of fuel, food supply crises, transport crises, and a certain lack of harmony between the various branches of industry. At the present time we are in the midst of a crisis of the growing industry, of growing agriculture; a crisis induced by the exigencies of the goods traffic between these, although as early as the beginning of the summer, measures were taken to place the goods at the disposal of the peasants. The crisis did not arise through any accumulation of goods in the warehouses of the manufacturers, but in the warehouses of the co-operatives and commercial organs, and has been principally due to the disparity in price of agricultural products and the products of factory industry.

I suppose that you are all familiar with the “scissors” depicted in a number of journals, graphically illustrating this disparity in prices by two diverging lines. The two blades of the “scissors” have now approached nearer to one another again.

The prices of industrial products, which in October were at 1.72 in comparison with the average level of prices, had fallen to 1.52 by 11. December, whilst agricultural goods have risen in price; the latter rose from 0,54 on 1. October in comparison with the total index, to 0,69 on 11. December; thus the angle of the “scissors”, which was 3,2 on 1. October, was reduced to 2,2 by 11. December. The question of this crisis is of fundamental importance for the whole of the further economic policy of our Party. When we introduced the New Economic Policy, comrade Lenin’s address as well as a number of other responsible utterances pointed out that this New Economic Policy inevitably implied crises. The Party, and our economists, must learn the lessons taught by these crises; above all we must learn the lesson taught by the crisis passed through this autumn. Why? Because, if we do not succeed in bringing about an exchange of goods between factory and village, we have not only no prospects for the further development of our industry, but shall rather be obliged to draw in a little. An enormous number of the population–the majority: 100 out of 120 millions–consists of small peasant producers. The economic tie uniting workers and peasants is the fact that the peasants supply raw materials and food to the town on the one hand, whilst on the other hand these same peasants are the main purchasers for the products of industry, purchasers who can secure for industry an uninterrupted increase in the demand for its products. We have a peasantry numbering hundreds of millions, and if we can only form a link with this peasantry, if only to a certain extent, if every peasant would buy a little from the town, then we have the prospect of possibilities for an uninterrupted and colossal growth of our industry on the basis of this mass market. But if this connection is not set up, then industry will have to continue to adapt itself to the consumption of the city markets, of the workers, of the petty and greater bourgeoisie. What capacity for absorption is possessed by the market now, and why is the question of the crisis at present the most important one for us?

During the past year, industry was able to record the successes of which I have spoken chiefly (to seven tenths) thanks to the city and the city markets. The city market is more solvent, if only for the reason that here the working wages, that is, the income of the most extensive city buyer, the workman, is calculated in goods roubles, and has risen steadily. A calculation in goods roubles signifies that higher prices are being taken into account. In precisely the same way, the employees, the NEP men, the petty bourgeoisie, the small citizens, have all been made more solvent than the peasantry in consequence of the general restoration of town life, and industry has grown, become stronger, and developed, on the basis of this solvent market.

Industry suffered defeat when it attempted to open up a formal connection with the less solvent peasant market, though this is potentially much more powerful than the city market. The fact that industry has adapted itself the whole time to the city market, and that it–to its own surprise–has suffered defeat in the peasant market, is chiefly explicable by the fact that the paragraphs of the resolution passed by the 12. Party Congress, and introduced into the original draft of this resolution on the decision of the plenary session of the Central, have not been carried out in actual practice. Industry, seeing its basis in a steadily growing city market, lost sight of the peasantry or at least it did not deem it to be its most urgent task to do its utmost possible for winning the peasant market, either with regard to choice and quality of the goods, or with regard to price policy. This showed itself in the calculations. A large number of calculations show outlays which could have been postponed, as for instance the cost of thorough restorations, the costs for new buildings, the reconstitution of ground capital, etc. Industry must become fully conscious of the fact that the fate of its development is dependent on capturing the peasant market, that price policy must above all be ruled by this consideration, and that there are many outlays which must be postponed until such time as industry has won the possibility of increasing its revenues on the basis of an extended peasant market and of an increased mass production.

The possibility of realizing a policy of higher prices has been afforded by the organization system of our industry, in the form of the system of trusts and monopoly syndicates.

This system suffers from two defects; in the first place the number of syndicates is somewhat larger than need be, or is demanded by economic interests; in the second place the monopolist organization of the syndicates is not utilized as it should be, that is, it is not properly utilized for the purposes of the “alliance” between workers and peasants, and for the reduction of prices.

At the same time I find it a mistake to raise objections against all centralization and every monopoly, objections bound to lead to the dismemberment of our industry into separate undertakings competing with one another. When we once have an organized socialist economic system, it will be centralized and monopolized in a high degree. Every exaggeration of centralization must be done away with, measures must be taken for the further development of the auto-activity of the separate economic units, and, what is the main thing, a systematic guidance of industry in the system of its organization, and in the activity of the regulating organs themselves, must be secured.

As I already mentioned, the blades of the “scissors” have approached by a third nearer to one another than in October. This is the result of the rise in the price of corn (on an average 0,56 and 0,69 in comparison with the total goods index figure) attendant on increased purchases, the export of grain, and the end of the main campaign for collecting taxes in kind; it is on the other hand also the result of a reduction in price of the products of industry. This has implied a livelier exchange of goods between town and country. The crisis is no longer acute, but it has not yet been overcome. It is necessary that the blades of the “scissors” approach each other much more nearly, and the goods turnover must be greater. This is a task which cannot be simply solved straightaway on command, it is a matter of systematic and persevering daily work.

At the 12. Party Congress there were two factors especially emphasized in the discussion on economic questions, factors of actual and burning interest for the present period. These were the questions of private capital and the organization of trade. I do not know whether there is any platform or project according to which the New Economic Policy is to be brought to an end economic policy is just now beginning, and the Central does not know this for the reason that the discussion on the tasks of the economic policy is just now beginning, and the Central does not yet know the objections to be raised against its resolution project.

In order that there may be no doubt as to the attitude of the Party Central towards proposals referring to a return to war communism, should such proposals be made, the Party Central has included in its resolution the intimation that such proposals are to meet with unqualified rejection. But are there other reforms necessary in the regime of the new economic policy, and if so, what are these? The reply to this question depends mainly on the extent to which private capital has grown and flourishes in our society, and what importance it has attained. When we went over to the New Economic Policy, every speech delivered on the subject, whether by members of the present opposition or by members of the present majority, emphasized that under this New Economic Policy the state must keep in its own hands all the essential factors of economic and industrial life, and place everything else in private hands, with mixed companies, etc. Up to now we have not been able to do this. Neither our leasing nor our concession policy has led to any very great success up to now, and even today there are innumerable small undertakings on our hands, which could be carried on by other people without the slightest danger to us. Last year our concession policy led to great results, but even these results are quite inadequate in comparison with that which could be accomplished for the economic life of our country with the aid of foreign capital. At the present time, the role and significance of private capital is confined to the sphere of commerce.

In commerce, a dominant position is filled by small private capital When considering commercial questions, we must not forget that, at the time when we went over to the New Economic Policy, no trade existed, and no trade apparatus, with the exception of the hoarders. The population was supplied with food through the agency of the People’s Commissariat for food supplies, without any intervention of money.

What does the commercial apparatus represent at the present moment? Wholesale trade is mainly in the hands of the state (77,4% of the total wholesale trade turnover); taken together with the undertakings in the hands of the co-operatives, state trade comprises 85,5% of the total turnover of big trade.

With regard to medium trade (big and petty trade) about one half is in the hands of the state and co-operatives (49,6%), and the other half with private capital, to which 50,4% of the total turnover of medium trade falls.

Petty trade is mainly in the hands of private capital (83,4% of the total petty trade turnover). I have the statements of the People’s Commissariat for Home Trade, worked out on the basis of returns issued by the Peoples Commissariat for Finance with reference to the trade permits issued for the first quarter of 1923. The total number of trade permits issued during this period was 476,351, of which 66% or 314,000 fall to the first and second categories. (Under “first category” we have here to understand retail trade, etc.) Commercial undertakings belonging to private persons, to the number of about 100,000, form the third category, 99% of the 314,000 undertakings counting to the first and second categories belong to private trade. What do these 314,000 undertakings belonging to the first and second categories, represent? The reply to this question is to be found in the following points from the law on trade permits, which require no further comment.

“Under the first category is to be understood trade in certain enumerated articles at weekly markets, in market places and other places, and sold personally out of the hand, from the ground, or from small sales tables, from sacks, baskets, boxes, receptacles, etc., carried by one person and containing the whole stock of goods”… “The second category includes trade carried on by one person, or with the help of a member of the family, for the sale of goods not contained in a special enumeration, and sold a) on movable devices of inconsiderable extent (market stalls, tables, portable stalls, small wagons, boats), at weekly markets, market places and other places; b) in small permanent premises not possessing the properties of a room (kiosques, garrets, sheds, tents, corners), the dimensions of which do not exceed six feet square, and in which the purchasers cannot enter.”

These are the two fundamental categories of retail tradesmen who have about 70% of all trading enterprises in their hands. I should now like to read you an extraordinary document characterizing the manner in which trade is carried on in the villages. In this document we read: Permanent private trading undertakings do not exist in rural districts. All local private dealers trade only at the markets and fairs of their own and other districts.” (From the inquiry made in the Schadrinsk district, Smolinskoye rural district.)

“Except on the occasion of weekly markets and other fairs, there have been neither peddlers nor dealers selling from carts in Smolinskoye. Dealers come in carts to other places, selling butter, fish, tea, and fancy goods.” (From the results of the inquiry held in the rural district of Smolinskoye, in the Schadrinsk district). “There are no peddlers, either on foot or in carts, except on market days.” (From the inquiry held in the rural district of Mechonskoye, in the district of Schadrinsk.)

I could here adduce endless local information showing that with regard to trade in villages and rural districts, the conditions obtaining are so Asiatic that there not only no retail shops, but not even peddlers. Where such a state of affairs obtains, the private retail business is naturally a step forwards in comparison to present conditions. It is impossible that “state capitalism” should set itself the task, after only three years of the new economic policy, of attaining a state of affairs in which only a small number of state organs is required forming an immediate connection between the factory and the consumer. But the conditions at present obtaining in the sphere of trade make us face the question in its full extent.

How much has private capital earned by trade? At first the sum of 600 millions was named, and incorrectly designated as profit, or as the gains accumulated by the private dealers. The figure of 600 millions is the result of approximate calculations. It is possible that more has been earned by trade, or it may be less, but in any case it must not be forgotten that this sum includes the outlay required for the transport and protection of the goods, for the maintenance of employees, for keeping up premises, etc. This profit falls to about 4,000 private dealers. It goes without saying that it would be infinitely preferable if this profit–or a great part of it–were to remain in the hands of state or co-operative enterprise. Although it must be admitted that under present conditions private capital has not grown to an extent rendering it dangerous to our system or to the rule of our Party, still it must be said that our economics contain one sphere, the spere of commerce, in which private capital has begun to assume a dominant and ruling position, and therefore a position dangerous to us. What measures are to be taken to avoid this danger? The most important are the two following:

The development of co-operative trade and the regulation of private trade.

Propositions have also been made to the effect that state commerce should be organized on a system similar to that on which the vodka trade was organized under the Czar. That is, an enormous number of retail shops should be opened in the villages and rural districts, and salesmen engaged for these shops, which would then sell the state goods. In one discussion I named this idea a bureaucratic Utopia. If we are already being defrauded at the present day by the trust at Bogorodek-Stschelkovo, which is not far from Moscow, what will happen to us when we appoint commercial assistants in all the sequestered rural districts of the country, and try to sell our goods in such shops? I am fully convinced that within a very short time there would be a great many rural districts in which we should not be able to find a trace of our goods, money, commercial assistants, or shops.

The main responsibility and duties attendant on the organization of retail trade must be laid upon the cooperatives. It is the great mistake of cooperation and state commerce that they do not compete with private trade with regard to cheaper selling prices, but with reference to the attainment of greater profits. The result has been that the peasants and workers have found no difference between the state and cooperative enterprises on the one hand, and the private dealer on the other, and had thus no inducement to further the cooperative organization, and to support state trade against private trade. The trend of state and cooperative activity in commercial matters must undergo an alteration, so that the question of the organization of primary cooperative nuclei may be placed on our agenda to its full extent, and so that cooperative and state commerce may be able to cope successfully with private trade in every rural district and lower the prices. At the present time, the peddler in the villages is a trade monopolist, and can demand any price he likes, undisturbed by competition. But as soon as competition appears, the private dealer and peddler alike will lower their prices and content themselves with smaller profits, and in many cases, especially in the peddling trade, the state organs will gain the upper hand.

The second thing that must be undertaken in the sphere of commerce is the necessary regulation.

I must say that before the commission appointed for the “scissors” question submitted to the Central a motion for the regulation of retail selling prices, its members vacillated for some time. It appeared to us that the question was not so much one of principle, or of any definite viewpoint, but was much more a question of actual practice: the possibilities existing for the execution and realization of the regulation of retail selling prices in our country in the year 1923, given the present conditions obtaining in the Party, in our economics, and the Soviet apparatus. It need not be said that we cannot regulate the prices on all the market stalls of the dealers belonging to the first and second categories. But even if we take the permanent retail shops, trade may here be easily converted from legal to illegal. If secret trade has hitherto been carried on in corn brandy, why should it not be carried on in the future with petroleum or anything else, if this should appear advantageous? We have decided to confine ourselves experimentally to three articles only–salt, petroleum, and sugar–and to regulate the retail prices of these. We propose to fix the maximum prices for these products, making these prices valid as far as and including the district towns. Further than this into the rural district and the village–we shall not go, for here we are confronted by complete lack of roads, with peddlers’ trade, with occasional fairs, or with secret trade. The cooperative organizations must of course reach into the remotest and least known villages.

With respect to private commercial capital in the towns, the taxation apparatus must be set in motion where there is an undue degree of accumulation, especially as regards those revenues of private capital which have so far escaped taxation.

I still have two questions: that of financial policy and that of the planning principle. I shall touch upon these briefly. With regard to financial policy, I must admit that I had expected greater differences of opinion, and was extraordinarily pleased when I heard from comrade Preobrashensky that he is in agreement with the Central in the fundamental question of financial policy with reference to the directions issued by the Party with respect to the transition to stable currency. This might have been a cause of fundamental differences in opinion. But if there is agreement on this point. I do not believe that any serious difference of opinion or disagreement is imaginable on essentials.

I already stated, at the commencement of my address, that we do not in the least deny that there have been many mistakes made in all these spheres, but I wish to maintain one thing only, and that is, that as soon as these defects were recognized, the Central and comrade Sokolinov took every possible measure for their removal. This we did with reference to buying up grain, and went so far here that the Political Bureau was occupied every week with the question of financing this operation; we also did our utmost in the wages question, and in a large number of other cases. Is a repetition of these faults imaginable? I think that it may very well be imagined. As against the 400,000 or 500,000 Party comrades whom we have, and of whom a great number are employed in the workshops and in the villages, we have hundreds of thousands of Soviet employees, and all these Soviet employees adopt an attitude towards the execution of our measures which is very different to that of Party comrades. It is quite impossible to hope that under such conditions no bureaucratic distortion will occur.

The question of the struggle against bureaucracy, of the distortions which it causes, and of the structure of the Soviet apparatus in such important questions as finance, the collection of the taxes in kind, etc. from foreign or neutral elements, is naturally a question of great importance, and a financial problem of the greatest difficulty.

In the sphere of finance–we shall not go into the separate errors committed, or calculate the separate distortions which I admit have occurred, and with which I personally am better acquainted than anyone else, as I have come into conflict with them oftener than anyone else in my capacity as “apparatus man” in the Council for Labour and Defence of Country–our policy has been correct in all fundamental questions, and brought great success to our Party. This success is shown by the budget. In the first place we have for the first time a real information budget. Time was when the Soviet congress, on Lenin’s motion, confirmed something under the name of a “budget” which had not the slightest resemblance to a budget, and had this published all over the globe. On no occasion did he feel himself in so unpleasant a situation as when he signed some piece of nonsense as a budget and submitted it to the All Russian Soviet Congress for acceptance. Now we have attained considerable success in the direction of drawing up an informatory quarterly budget, and, what is the main point, in chervonetz currency. At one time everything was issued in accordance with some index figure. Each institution had not only one index figure, but several, and the figure most advantageous at the moment was employed. At the present juncture the whole budget has been drawn up in chervonetz currency, and the sums granted will be issued in chervonetz currency stabilizing this yet further.