Briggs reports on the intervention of the African Blood Brotherhood in Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association’s second international convention held at New York City’s Liberty Hall.

‘The Negro Convention’ by C.B. Valentine (Cyril Briggs) from The Toiler. No. 190. October 1, 1921.

The Second International Convention of Negroes held at Liberty Hall, New York, during the entire month of August, was called by Marcus Garvey, President-General of the “Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League” and “Provisional President of Africa,” “President of the Black Star Line,” etc., etc.

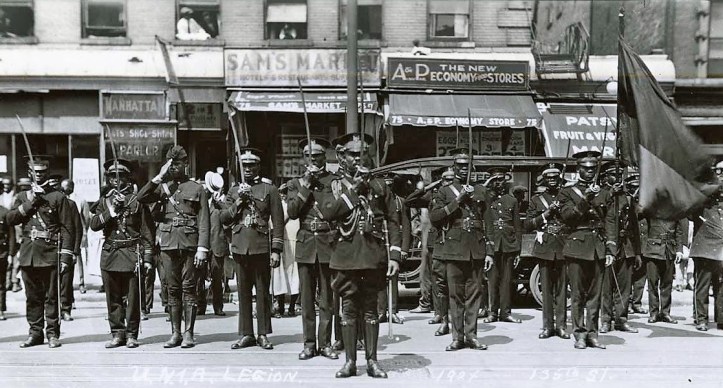

The convention was opened amid a wild fanfare on the first day of August. There was a parade in Harlem in the afternoon, and a mass meeting at the 69th Regiment Armory in the evening. The Metropolitan daily press was forced to sit up and notice the “doin’s.” The opening noise attended to that. The Potentate made the opening address. The Potentate is the Hon. Gabriel Johnson, Mayor of Monrovia, Liberia. He represents “the African Connection” of the Movement, and for that favor is paid $500 a month.

All delegates who were elected by their divisions to represent them for a 5-year period of conventions were given the rank of deputies and the privilege of being addressed as the “Honorable So-and-So.” Later on there was a Grand Court Reception in which the guests were “presented to the Potentate” and several knighthoods and one “ladyship” were created.

A number of negro organizations responded to the call and sent delegates to the convention. Most important among these was the African Blood Brotherhood, a radical negro organization boasting the legend “created for immediate protection and ultimate liberation of negroes everywhere,” and already having on its record the accusation of having organized and directed negroes in self-defense in the Tulsa, Oklahoma riots in June 1921. The presence of the African Blood Brotherhood delegation made the convention a really memorable affair and of tremendous import to the radical world, for the ABB delegates sternly set their faces from the start against the romantic glamour, “mock heroics and titled tomfoolery” which Mr. Garvey was attempting to substitute for real constructive action.

The ABB delegation, effectively backed by its organization which issued a manifesto at the opening of the Congress and followed up with a weekly bulletin and other literature, demanded among other things a constructive program for “the guidance of the negro race in the struggle for liberation,” and suggested and agitated before the congress the creation of a federation of existing negro organizations “in order to present a united and formidable front to the enemy,” and the adoption of a program calling for means “to raise and protect the standard of living of the negro people,” to “stop the mob-murder of our people and to protect them against sinister secret societies of cracker whites, and to fight the ever expanding peonage system.” They further demanded that Soviet Russia be endorsed by the congress and the real foes of the negro race denounced.

These constructive demands, effectively presented and supported by widespread agitation, had the effect of a bomb upon the officials of the convention, all of whom were UNIA members, and there was immediately evident a spirit of revolt among the dissatisfied elements of the UNIA majority. This revolt the ABB delegates tried skillfully to direct, but evidently found complications and adverse forces in operation, for the revolt never became effective. To conceive of the nature of these difficulties and their causes it must be remembered that not only were the UNIA delegates in the vast majority but that among them were many who were possessed of a blind, unquestioning loyalty to Marcus Garvey as the “Moses of the Negro Race.”

What is Garveyism? A shrewd mixture of racialism, religion, and nationalistic fanaticism. It is without doubt an historic product, and has its roots in the past oppression of the negro. It is one of the signs of his awakening, the noisiest, though not the most effective, challenge to the white world—to the entire white world, for Garveyism looks at every white face as per se an enemy. Herein lies one of the chief reasons for the bitter opposition it has met from the class-conscious negro worker. It is a step in advance of his religious slavery, wherein the negro was completely dominated by his preachers and subserviently subscribed to the philosophy of giving up all the world to his exploiters so long as they would leave him “his Jesus.”

The day sessions of the convention did not reveal the secret of Garvey’s power over the majority of the delegates and the gallery. It is only at the informal night sessions where emotionalism runs riot under the expert priest-craft of Marcus Garvey that the secret can be discovered. These night sessions were designed to flood the atmosphere with Garveyism and whip into line all recalcitrant delegates by the sheer power of fiercely concentrated fanaticism. Rituals were chanted, hymns sung, fiery racialistic speeches made, with an almost continuous accompaniment of flag-waving (the Red, Black, and Green of the UNIA) and parading of uniformed Legionnaires, Black Cross nurses, and other forces of the “UNIA Government.”

At first the agitation carried on by the ABB delegation was quietly ignored by the officers of the convention after the first shock. But it soon began to show its effect in the growing spirit of revolt, and when, on the 25th day of the Congress, the third weekly bulletin of the ABB was distributed among the delegates with a headline declaring “Negro Congress at a Standstill—Many Delegates Dissatisfied with Failure to Produce Results.” The crisis of the convention had arrived!

As to the sins of omission, the Bulletin claimed that it “had formulated no general program for the negro race and no specific program for the various sections of the negro race (the American, West Indian, etc.), it “had devised no means for the liberation of Africa and the support of the Mohammedan and Ethiopian movements, the Egyptian and Moorish struggles, as means toward that end,” it had “taken no steps toward raising and protecting the standard of living,” it “had ignored the suggestion to consolidate the strength of the negro through a federation of negro organizations,” it “had refused to condemn the capitalist oppressors of the negro,” it “had failed to endorse the friends and natural allies of the negro race,” it “had failed to protest the rape and continued occupation of Haiti by the United States,” it “had failed to repudiate the ridiculous proposition of Mr. Garvey that negroes can be loyal to the flags of the nations that oppress them and liberate themselves from that oppression at the same time, that negroes living under the French and British flags can be loyal to those flags and still effect the liberation of Africa from the domination of those flags.”

Following the distribution of the Bulletin at the noon recess Mr. Garvey in a passionate outburst denounced the ABB as traitors and Bolshevist agents, while one of his henchmen put forward a resolution calling for the expulsion from the convention of the ABB delegates. In the absence of these delegates, objection to the resolution was made by several UNIA delegates, but the motion was passed by a majority vote, with many abstentions. The ABB delegates were then read out of the convention.

In answer to the action of the Garvey-controlled majority of the convention, the African Blood Brotherhood took its case to the negro masses by means of pamphlets, news releases in the negro press, and mass meetings. There the case rests for the present with the odds evidently in favor of the ABB and the popularity of Marcus Garvey clearly on the wane.

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n190-oct-01-1921-Toil-nyplmf.pdf