Almost immediately after the failed ‘German October’ of 1923 an internal letter, the ‘Declaration of 46’, was sent to the Politburo by Trotsky and others beginning the Left Opposition. Ill with malaria, Trotsky was recovering in the Caucasus and unable to attend December, 1923’s Central Committee Plenum in which the debate would be joined. He began a public series six of articles in Pravda outlining the Opposition’s views, what is now known as ‘The New Course.’ Below are the first three as originally translated: Groups and Factional Formations, The Question of the Party Generations, and The Social Composition of the Party.

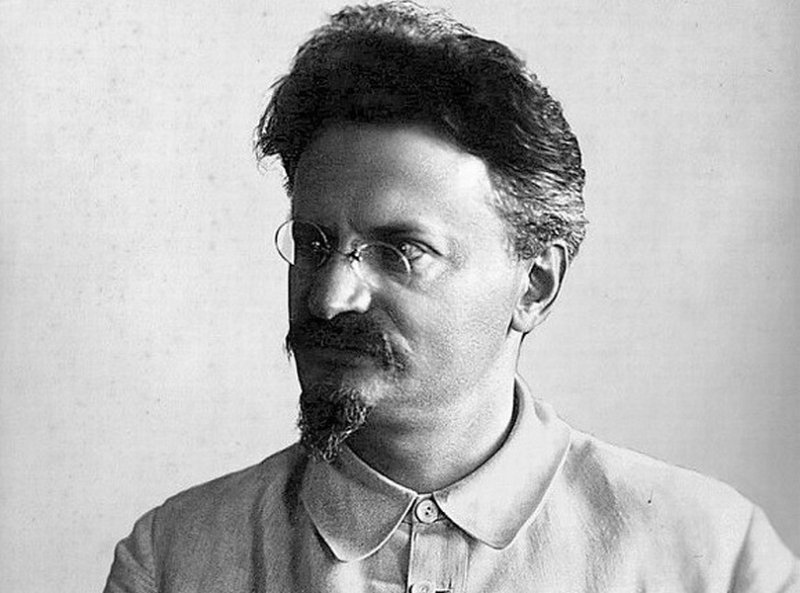

‘The New Course’ by Leon Trotzky from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 16. February 29, 1924.

I. Groupings and Fraction Formations.

I am endeavouring to give in a number of articles an estimation of those questions which now form the center of the Party discussions. I shall take pains that my words shall be of an informative character, taking into account the rank and file of the Party without which it is futile to speak about Party democracy. On the part of the reader, expect a quiet and reflective attitude towards the subject. First of all, let us try to understand one another; there will be time enough afterwards to grow heated. L.T.

***

The question of groupings and fractions has formed the central point in the discussion. In this sphere, it is necessary to express oneself with the greatest clearness, as the question is a very delicate and responsible one. And moreover, it is generally put in an erroneous manner.

We are the only party in the country, and in the period of dictatorship this cannot be otherwise. The various needs of the working class, of the peasantry, of the state apparatus and of its personal staff exert a pressure on our Party and seek through its mediumship to find political expression. The difficulties and contradictions of development, the temporary incongruity of the interests of the various parts of the proletariat, or of the proletariat as a whole, and of the peasantry–all this exerts pressure on the Party through its workers’ and peasants’ nuclei, through the state apparatus and through the student youth. Even episodal, temporary disagreements and shadings of opinions may, in one or the other remote instance, be the expression of the pressure of certain social interests; the episodal disagreements and temporary groupings of opinions can, under certain conditions transform themselves into permanent groupings; the latter, on their part, can develop sooner or later, into organized fractions, and finally, a well-formed fraction, opposing itself to other parts of the Party, will thereby surrender itself to pressure from without the Party. Such are the dialectics of inner Party groupings in a period when the Communist Party is compelled to monopolize the leadership of political life within its hands.

What conclusion is to be drawn from this? If you do not want fractions–there must be no permanent groupings; if you do not want permanent groupings–avoid temporary groupings; finally, in order to protect the Party from temporary groupings, it is necessary that within the Party in general, there be no disagreements, because where there are two opinions, people always begin to group themselves accordingly. But how are we, on the other hand, to avoid disagreements in a party of half a million, which is leading the life of the country under extremely complicated and difficult conditions? That is the essential contradiction which is rooted in the very situation of the Party of proletarian dictatorship itself, and such a contradiction cannot be overcome by mere formal treatment.

Those adherents of the old policy who vote for the resolution of the C.C. in the conviction that all will remain as before, judge for example as follows: Hardly were the bands of the Party apparatus somewhat loosened, when at once arose certain tendencies towards groupings of all kinds: the bands must be drawn closer. This short-sighted wisdom is filling dozens of speeches and articles “against fractionism”. These comrades think in the depths of their souls, that the resolution of the C.C. is either a political fault which must be cancelled, or a trick of the apparatus which must be taken advantage of. I think that they commit a very crude error. And if anything can bring about the greatest disorganization of the Party, it is the obstinate clinging to the old policy under the appearance of respectful subjection to the new one.

The public opinion of the Party unavoidably forms itself by contradictions and disagreements. To restrict this process only to the apparatus, giving afterwards to the Party the finished results in the form of slogans, instructions etc., means an ideological and political weakening of the Party. To make the whole Party participate in the formation of decisions, means encountering temporary ideological groupings, adding to this the danger of converting them into permanent groupings and even into fractions. What is the proper thing to do? Is there no way out? Is there no place in the Party for a middle course between a domination of party “tranquility” and the domination of party-splitting fractionism? No doubt, such a middle course exists, and the whole task of the inner leading of the Party consists in finding it in every single case, in particular at a turning point, in accordance with the given concrete situation.

The resolution of the C.C. frankly announces, that a bureaucratic regime within the Party is one of the sources of fraction groupings. This truth hardly needs any proofs at present. The old policy was far from being a “developed” democracy and, in spite of that, not only failed to protect the Party from illegal fraction formations, but also from that outburst of the discussion which in itself–it would be ridiculous to shut our eyes to this fact!–is pregnant with the formation of temporary or permanent groupings. In order to avoid this, it is necessary that the leading Party organs give ear to the voice of the broad Party masses and that they do not consider any criticism as an expression of fractionism, and thereby drive conscientious and disciplined Party members towards aloofness and fractionism.

But would not such an arrangement of the question regarding the fractions mean a justification of the Myasnikov (*Leader of the “Workers Group” Opposition in the Russian C.P. who was expelled from the Party. Ed.) mischief?–we hear the voice of the supreme bureaucratic wisdom asking. Is it really so? No! First, the whole sentence which we underline, is in itself an exact quotation of the resolution of the C.C. And secondly, since when has an explanation been the same as a justification? To say that an abscess has come as a result of a bad blood circulation deriving from insufficient influx of oxygen, does not at all mean “to justify” the abscess and to consider it a normal necessary part of the human organism. There is only one conclusion: the abscess must be opened and cleansed with antiseptic, and, in addition to this–and this is the most important–the window must be opened, so that the fresh air may better oxygenate the blood. But the evil is precisely in this, that the most militant wing of the adherents of the old policy of the apparatus is profoundly convinced of the resolution of the C.C. being an erroneous one, in particular those paragraphs, where bureaucratism is declared to be one of the sources of fractionism. And if these adherents of the old policy do not utter this loudly, this is only done out of formal considerations, just as in general all their thinking is filled with the spirit of formalism which is the ideological basis of bueraucratism.

Ay, fractions constitute a very great evil under the present conditions, and groupings even temporary ones can transform themselves into fractions. But, as experience proves, it is quite futile to declare groupings and fractions an evil, in order thereby to render their arising impossible. There is the need for certain politics, for an appropriate policy, in order to obtain this result in reality, by adapting oneself in every case to the concrete situation.

It is sufficient to penetrate in a proper manner into the history of our Party, if only into that regarding the period of the revolution, i.e. that very period when fractionism became particularly dangerous, and it becomes clear, that the fight against such a danger is in no case exhausted with a mere formal condemnation and the prohibition of groupings.

The most threatening disagreement in the Party arose in connection with the greatest task of world history, the task of seizing power in the Autumn of 1917. The acuteness of the question, along with the tremendous rapidity of the events, afforded to the disagreements almost at once an acutely fraction-like character: those who were opposed to the seizure of power, without even wishing this, allied themselves in reality with non-party elements, published their declarations in the columns of the non-party press, etc. Party unity hung in the balance. By what means was it possible to avoid a schism? Only by the rapid development of the events and by their victorious solution. The schism would have been inevitable, if the events had been prolonged for several months, and still more if the insurrection had ended with a defeat. By a violent offensive, our Party, firmly led by the majority of the C.C., over-rode the opposition, power was conquered, and the opposition, very small in numbers, but highly qualified in the Party sense, accepted the October event as an accomplished fact and worked accordingly. Fractionism and threatening schism were in this case defeated, not by means of formalities and statutes, but by means of revolutionary action.

The second great disagreement arose in connection with the question of the Brest-Litovsk peace. The adherents of the revolutionary war gathered themselves into a definite fraction with its own central organ, etc. I do not know, what basis there is to the anecdote which came up recently as to how Comrade Bukarin was on the point of arresting the government of Comrade Lenin. Generally speaking, this is somewhat like a second-rate tale adventure by Maine Read or a communist…Pinkerton affair. But we can trust the Istpart (Commission for the Study of Party History) to get to the bottom of the question. There is no doubt, however, that the existence of a left communist fraction involved an extreme danger to the Party unity. To have led the matter up to a schism would not, at that time, have caused mu h trouble and would not have required on the part of the leaders…much cleverness. It would have sufficed simply to declare the left Communist fraction prohibited. The Party, however, adopted, more complicated methods: discussions, explanations, tests based on political experience, reconciling itself for the time being with such irregular and threatening phenomena as the existence of an organized fraction within the Party.

We were experiencing within the Party a rather strong and obstinate grouping as to questions of military structure. Essentially, this opposition was against constructing the regular army with all the consequences deriving therefrom: centralized military apparatus, attracting of specialists etc. For several moments the fight assumed an extremely acute character. But here also, as in October, the trial by arms was a help. Various roughnesses and exaggerations of the official military policy were reduced–not without the influence of the opposition–not only without detriment to, but even with advantage to the centralized structure of the regular army. The opposition was gradually absorbed. Very many of its most active representatives have not only been attracted to military work, but have also assumed in it some of the most responsible positions.

Very distinct groupings were to be observed in the period of the memorable discussion on trade unions. At the present time, when we have the possibility of looking backward on this period as a whole, and to illuminate it with all our subsequent experience, it becomes quite obvious that the dispute in no way dealt with the trade unions or even with the workers’ democracy: By means of these disputes a profound impotency of the Party was revealed, the cause of which was the economic regime of war-communism, which was maintained too long. The entire economic organism of the country was involved in an impasse. Under the pretext of a formal discussion over the role of the trade unions and party democracy, there was proceeding an indirect investigation of new economic paths. A way out of this impasse was found in the abolition of food requisitioning and grain monopoly and in the gradual freeing of the state industry from the fetters of war centrals bureaucracy. These historical decisions were adopted unanimously, and they completely put an end to the discussion on trade unions, the more so that, on the basis of the Nep, the role of the trade unions itself appeared in a completely new light, and the resolution on trade unions had to be radically modified after some months.

The most lasting, and on account of many of its aspects, the most dangerous grouping was that of the “Workers’ opposition”. In it were reflected, in exaggerated form, both the contradiction of war communism and some mistakes of the Party, as well as the fundamental objective difficulties of socialist construction. But here also the matter was not restricted to a merely formal prohibition. As to decisions regarding the questions of Party democracy, mere formal steps were taken, but as to purging the Party, extremely important practical steps were taken giving heed to all, that was proper and sound in the criticism and in the demands of the “Workers’ opposition”. And, what is of the most importance, thanks to the fact that the Party, by means of its economic decisions and measures of exceptional importance had put an essential end to the disagreements and groupings, the formal prohibition of fraction formations on the 10th Party Congress became possible, i.e., promising real results. But it is self-evident–and this is proved by the experience of the past, and by sound political reason–that the mere prohibition in itself did not include an absolute, or in general, any serious guarantee for preserving the Party from new ideological and organizatory groupings. The principal guarantee consists in the appropriateness of the leadership, in the timely attention paid to all demands of development reflected in the Party, in the adaptability of the Party apparatus, which has not to paralyze but to organize the Party initiative and not to be afraid of critical voices and of the bogey of fractionism. In general the cause of intimidation is in most cases to be found in fear! The decision of the 10th Congress forbidding fractionism can only have an auxiliary character, but in itself it does not give the solution to each and every inner difficulty. It would be too primitive an organizatory fetishism to believe that the bare decision– without regard to the course of the Party, to the mistakes of leadership, to the conservatism of the apparatus, to the exterior influences etc., etc.–is capable of preserving us from groupings and conflicts deriving from fractions. Such an attitude is by itself a thorough deep-rooted piece of bureaucracy.

The most striking example of this is given by the history of the Petrograd organization. Shortly after the 10th Congress, at which groupings and fraction formations had been forbidden, there arose in Petrograd an acute organizatory struggle, which created two groupings sharply opposed one to another. The most simple solution would obviously have been to declare one of the groupings (at least one) nefarious, criminal, fraction-like etc. But the C.C. categorically rejected such a method which was proposed to it from Petrograd. The C.C. took upon itself to intermediate between the both Petrograd groupings and finally–it is true, not at once–insured not only their collaboration, but also their absorption in the organization. This example, which is of exceptional importance, should not be forgotten; it is unsurpassable as a means of clarifying certain bureaucratic heads.

We mentioned above that any kind of serious and permanent grouping in the party, and even more an organized fraction, tends to become the expression of certain special social interests. Every incorrect deviation, which gives rise to the formation of a group, can, in its development, become the expression of the interests of a class hostile or semi-hostile to the proletariat. But all this applies as a whole, and even in the first place, to bureaucratism. It is with this we must deal with first. That bureaucratism is an incorrect unsound deviation, this is, we hope so, admitted. And this being the case, so, in its development, it threatens to divert the Party from the correct way, that is from the class way. This is what constitutes its danger. But it is an extremely instructive and, in addition, a very disconcerting fact that those comrades who in the sharpest and most obstinate manner and sometimes even in a cruder manner than any others, insistently declare, that every disagreement, every grouping of opinions, even a temporary one, represents in itself the expression of different class interests, do not wish to apply the same criterion to bureaucratism. It is here however, that the social criterion is most justified, because in bureaucratism we have the fully developed evil, the obvious and indisputably harmful deviation, which has been officially condemned, but which is by no means extinct. And how is this to be immediately exterminated? But if bureaucratism is threatening, as is stated by the resolution of the C.C., to estrange the Party from the masses. and, as a consequence, to weaken the class character of the Party, it follows from this alone that the struggle against bureaucratism cannot in any event be identified a priori with any non-proletarian influences. On the contrary, the efforts of our Party to retain its proletarian character, must, unavoidably, call forth within the Party itself a defense against bureaucratism. No doubt, under the flag of this defense, various tendencies may be furthered, among them also incorrect, unsound, pernicious ones. These pernicious tendencies can only be revealed by means of a Marxist analysis of their ideological contents. But, to identify defense against bureaucratism, purely and formally with those groupings which are alleged to serve as a channel for strange influences, means being a definite “channel” for bureaucratic influences oneself.

The very idea, however, that disagreements within the Party, and groupings even more so, signify the struggle of various class influences, cannot be pronounced to be too primitive and crude. For example, as to the question, whether it was necessary to probe Poland with the bayonet in the year 1920, we had incidental disagreements among ourselves. Some were for a bolder policy, some for a more cautions one. Were there various class tendencies in this? Hardly anyone will venture to assert this. These were disagreements as to the estimation of the situation, of the forces, of the means. But the fundamental criterion of the estimation was one and the same, for both sides. The Party may not unfrequently solve this or that task by different means, and disagreements can arise as to which of these means will be the better, the shorter and the more economical. Disagreements of this kind, may, according to the character of the question, seize broad circles of the Party, but this will in no way absolutely mean that here there is proceeding the struggle of two class tendencies. There is no doubt that this will happen to us not once, but dozens of times in the future, because the path before us is a difficult one, and not only political tasks, but also, for instance, organizatory-economic questions of socialist construction will cause disagreements and temporary groupings of opinion. The political examination of all shades of thought by means of Marxist analysis, is always for our Party the most indispensable preventive measure. But it is precisely the concrete Marxist examination, and not the stereotyped formula, which latter only serves as a weapon of self-defense for bureaucratism. To examine and to sift that heterogeneous ideological political content, which is now rising against bureaucratism, and to discard all that is strange and harmful all this will be accomplished the more successfully, the more seriously we adopt the line of the New Policy. This, in turn, cannot be realized without a profound new orientation of the mind and of the self-assurance of the Party apparatus. But, instead of this, we witness a new offensive on the part of the Party apparatus which once for all, designates as fractionism any criticism against the–formally condemned, but not yet liquidated–old policy. If fractionism is dangerous–and it is so–then it is criminal to close ones eyes to the dangerousness of conservative-bureaucratic fractionism. It is precisely against this danger that the resolution adopted unanimously by the C.C. must be directed in the first place.

To preserve the unity of the Party is the most fundamental and urgent care of the overwhelming majority of the comrades. But here it is necessary to say frankly: if there is now a serious danger threatening the unity, or at least the unanimity, of the Party, then it is the rampant bureaucratism. It is precisely from this camp that voices are to be heard which cannot be designated other than provocatory ones. It is precisely this camp which has been rash enough to say: “we have no fear of schism!” It is precisely the representatives of this camp who rake over the past, seeking from it everything which could render the Party discussion still more embittered, artificially reviving the memories of old struggles and old schisms, in order to get the mind of the Party, imperceptibly and gradually, habituated to the idea of the possibility of such a monstrous suicidal crime, as a new schism. They wish to bring into collision the Party’s need for unity and its need for a less bureaucratic regime. If the Party were to adopt this course and were to sacrifice the most necessary vital elements of its own democracy, its only gain would be a sharpening of the inner struggle and the shattering of its fundamental pillars.

It is impossible to demand on the part of the Party, in the form of an ultimatum, a one-sided confidence in the apparatus, if one has no confidence in the Party itself. That is the very essence of the question. The prejudicial bureaucratic mistrust of the Party, of its consciousness as a party, and of its disciplinedness–that is the main cause of all the evils of the apparatus regime. The Party does not desire fractions and will not allow them. It is monstrous to assume that the Party will allow its apparatus to be destroyed, or that it will destroy it of itself. The Party knows that the apparatus consists of the most valuable elements, in whom is embodied a huge portion of the experiences deriving from the past. But it wants to renew the apparatus and would remind it that it is its apparatus, elected by it, and that it must not become estranged from it.

If one reflects, up to the last consequences, upon the situation created in the Party, especially as it revealed itself in the discussion, a two-fold perspective of further development becomes completely clear: Either the new ideological-organizatory orientation now proceeding in the Party, according to the line of the resolution of the C.C., will serve gradually as a step on the way of organic growth of the Party, as a beginning–of course as a mere beginning–of a new large chapter, and this will then be the most desirable solution for all of us and the most salutary for the Party. Then it will be easy to get rid of the exaggerations of discussions and oppositions and even more so of the vulgar-democratic tendencies of the Party. Or, instead of this, the Party apparatus having passed to a counter-offensive, will, to a greater or less extent, come under the influence of its most conservative elements and will, under the slogan of the struggle against fractionism, throw the Party back again to its previous position of tranquility”. This second way will be incomparably more painful, it will not, of course, retard the development of the Party, but it will force these developments to be gained only at the cost of strenuous efforts and heavy shatterings, because it will unnecessarily revive the harmful disintegrating anti-Party tendencies. Such are the two possibilities which are objectively opening out. The sense of my letter “The New Policy” was to help the Party to enter the first way, as being the more economical and sound one. And on the position of this letter I fully insist, repudiating the tendentious and mendacious interpretations of it.

II. The Question of the Party Generations

In one of the resolutions adopted during the Moscow discussion, I met with a complaint that the question of Party democracy had been complicated by disputes on the mutual relations of the generations, by personal attacks and so on. This complaint reveals a lack of clearness of thought. Personal attacks–that is one thing, and the question of the mutual relations of the generations–is quite another. To put forward at the present juncture the question of Party democracy without including an analysis of the personal composition of the Party–in respect to social status as well as to the age and length of political activity of the membership–would mean to make the question itself a futile one.

It is by no means a mere chance that the question of Party democracy arose in the first place, as a question of the mutual relations of the generations. Such a formulation of the question has been prepared by the entire past of our Party. In a schematic manner, one could divide this history into four periods: a) the pre-October preparation, extending over a quarter of a century, which is unique in history, b) October, c) the post-October period, d) the “New Policy”, i.e., the present opening period.

That the pre-October period, notwithstanding its richness in events, its complexity and the marked differences between its various phases, presented only the preparatory period, is fully admitted at the present time. October gave the ideological and organizatory test of the Party and of its ranks. By the term: October, we understand the most acute period of struggle for power, beginning approximately from the April theses of Comrade Lenin and ending with the practical seizure of the state apparatus. The October chapter which is to be measured by months, is, in its contents, no less important than the whole preparatory period, which is to be measured by years and decades. October not only afforded a faultless test (unique in its kind) of the great past of the Party, but it also became a source of greatest experience for the future. By means of October, the pre-October Party realized for the first time its true value.

After the conquering of power, there begins the rapid growth of the Party, and even its unsound swelling up. Like as to a powerful magnet, there are attracted to it not only the feebly conscious elements of the working class, but also obviously strange elements: Job-hunters, careerists and political parasites.

In this very chaotic period, the Party is only conserved as a Bolshevik Party by the force of the practical inner dictatorship of the old guard, tested by means of October. In questions involving any kind of principle, the new Party members–not only those from among the working class, but also the strange elements–accept without objection the leadership of the older generation. The careerist elements thought that by such an obedience, they could best secure their position in the Party. These elements, however, have deceived themselves. By means of a strict self-purging, the Party freed itself from them. Its ranks became thinner, but the self-confidence of the Party was raised. It can be said that the testing and purging of the Party marked the commencement of the period in which the post-October Party became conscious of itself for the first time as a collective body comprising half a million, which not only exists under the leadership of the old guard, but is also destined itself to get to the bottom of the principal questions of politics, to reflect and to decide. In this sense, the purging and the whole critical period connected with it, constitute something like an introduction to that complete turn which is now to be observed in the Party life, and which probably will be recorded in its history under the title of “The New Policy”.

It is necessary from the very outset clearly to understand one thing: the essence of the frictions and difficulties which we are at present experiencing does not consist in the secretaries having grown too big for their boots and that it is necessary to put them in their places, but in the fact that the Party as a whole is on the point of passing over to a higher historical class. It is as if the masses of the Party were saying to the leading Party apparatus: “You, comrades, have experience of the pre-October period which the great majority of us are lacking; but under your leadership we have obtained a post-October experience which is continually increasing in importance. And we not only wish to be led by you, but also to participate along with you in the leadership of the class. We desire this not merely because it is our right as Party members, but also because it is of vital necessity to the working class as whole. Without our rank and file experience, which is not merely taken into account by those above, but is actively brought into the life of the Party by ourselves, the leading Party apparatus would become bureaucratized; but we of the rank and file do not feel ourselves to be sufficiently equipped ideologically when confronting the non-party masses.”

The present turn, as has already been said, arose out of the entire preceding development. Molecular processes in the life and conscience of the Party which are not be observed on a superficial glance, have been preparing this turn far in advance. The market crisis gave a great impetus to the work of intellectual criticism. The approach of the German events compelled the Party to pull itself together. It was just at this moment that it became revealed with particularly striking clearness, to what an extent the Party was living on two different planes: on the higher–they decide on the lower–they only hear of decisions. A critical revision of the inner Party situation became, however, postponed as a result of the tense and anxious expectation of the imminent outbreak of the German events. When it became clear that this outbreak had been retarded by the course things were taking, the Party brought up for discussion the question of the New Policy.

As it has not unfrequently happened, the “old policy” precisely in the last months revealed its most repugnant and absolutely intolerable features of apparatus-like aloofness, of bureaucratic self-satisfaction and disregard of the moods, the thoughts and the demands of the Party. By its bureaucratic inertia, the apparatus, as a whole, came into conflict with the first efforts to bring up for discussion the question of a critical revision of the inner Party regime. This does not, of course, mean that the apparatus consists exclusively of bureaucratic elements, still less of any ingrained and incorrigible bureaucrats. Far from it! The overwhelming majority of the apparatus functionaries, having gone through the threatening critical period and having understood its significance, will learn much and will renounce much. The ideological-organizatory regrouping, which will arise out of the present moment of turning, will, in the end, have salutary consequences for the rank and file of the Party masses as well as for the apparatus. But within this apparatus, such as it proved to be at the beginning of the present crisis, the bureaucratic features have reached an extreme, in fact a dangerous development. And it is precisely these features which impart to the ideological regrouping which is now proceeding in the Party, such an acute character and which cannot help but give rise to justified anxieties.

It is sufficient to say that only 2 to 3 months ago the mere mention of the bureaucratism of the Party apparatus, of the immoderate pressure exerted by committees and secretaries, met with a haughty shrug of the shoulders or with an excited protest on the part of the responsible and authorized representatives of the old Party policy in the centre and in the provinces. A regime of appointments? Nothing of the kind! Officialism? Pure invention, opposition for opposition’s sake, and the like! These comrades honestly failed to note bureaucratic danger, of which they themselves were the carriers. It was only in response to decisive pushes from below, that they gradually began to admit that a certain degree of bureaucratism was existing, but only somewhere, in the peripheries of the organization, in single gouvernements and districts, that presented a deviation of practice from the correct line etc., etc. And this bureaucratism they interpreted as a simple survival of the war period, i.e. as something which would gradually disappear, though perhaps not quickly enough. It is superfluous to speak about the fundamental. erroneousness of such an attitude and of such an explanation. Bureaucratism is not a mere chance feature of single provincial organizations, but a general phenomenon. It does not proceed from the districts through the gouvernements, but rather in the opposite direction, from the centre through the gouvernements to the districts. It in no way constitutes a “survival” of the war period, but is in itself the result of the transference to the Party of methods and habits of administration accumulated precisely during the last years. The bureaucratism of the war period, no matter what degenerate forms it may have assumed in single cases, was a mere infant compared to the present bureaucratism which has accumulated under the conditions of peaceful development, when the Party apparatus, in spite of the ideological growth of the Party, obstinately continued to think and to decide for it.

Having regard to the foregoing, the unanimously adopted resolution of the C.C. on Party structure assumes a very great principle significance, which must be fully appreciated by the consciousness of the Party. It would indeed be unworthy to regard the matter, as though the whole essence of the decisions would result in a more “mild”, more “deferential” attitude on the part of the secretaries and the committees towards the Party masses, and in some organizatory-technical modifications. It is not for nothing that the resolution of the C.C. speaks of a new policy. The matter, of course, does not imply an infringement of the organizatory principles of Bolshevism, but their adaptation to the conditions of the new stage in the development of the Party. The question is, in the first place, that of the establishment of sounder mutual relations between the old Party members and the post-October majority of the Party members.

The theoretical preparations, the revolutionary tempering, the political experience, form the fundamental capital of the Party. And the custodians of this capital are, in the first place, the old members of the Party. On the other hand the Party, in its very nature, is a democratic organization, i. e. such a collective body, the course of which is determined by the thought and will of all its members. It is perfectly clear that in the highly complicated situation which immediately followed the October days, the Party was able to shape its course the more surely and correctly, the more it succeeded in utilizing the accumulated experience of the older generation, by entrusting representatives of the latter with the most responsible posts in the Party organization. On the other hand, this led and is leading directly to the older generation which forms the mainstay of the Party and is absorbed in questions of administrations, becoming accustomed to think and to decide for the Party, employing towards the Party masses, in the first place, the methods of a school pedagogue for training them for political life: Elementary courses in political science, examination as to knowledge of the Party, Party schools etc. Hence there follows the bureaucratizing of the Party apparatus, its aloofness, its self-contented inner life, in short, all those features which constitute a thoroughly negative side of the old policy. Concerning the dangers of the continuance of the life of the Party on two sharply defined planes, I have spoken in my letter dealing with the young ones and the old ones in the Party, in which by the term “young ones” I have in mind, of course, not only the student youth, but in general, the whole post-October generation of the Party, beginning, in the first place, with the workshop and factory nuclei.

Wherein was that imperfection expressed with which the Party became more and more afflicted? Precisely in this, that the mass of the Party members said to themselves, or felt: “In the Party apparatus they may think and decide rightly or not, but in any event they too often think and decide without us and for us. But when from our side there is raised a voice of disagreement, of doubt, of objection or of criticism, we receive in response a rebuff, a reminder of discipline and in most cases a charge of making opposition and even of forming fractions. We are devoted to the Party, right up to the last, and are prepared to sacrifice everything for it. But we do desire to take an active and intelligent part in the elaboration of the Party opinion and in the determination of the course of Party action!” There is no doubt that the first uttered expressions of these moods of the rank and file were not timely remarked and taken into consideration by the leading Party apparatus; and this fact formed one of the most important causes of the formation’ of those anti-Party groupings within the Party, the importance of which, of course, must not be exaggerated, but the warning import of which it would be unwise to underestimate.

The chief danger of the old policy, as it became moulded as a result of the great historical causes, as well as of our faults, consisted in its tendency to oppose some thousand comrades forming the core–to the whole remaining mass of the Party, regarded as so much passive material to be worked upon. If this regime were to be stubbornly maintained in the future, it would undoubtedly threaten finally to provoke a degeneration of the Party–and moreover, at both poles, that is, among the junior members, as well as among the old stalwarts. Regarding the old proletarian foundation of the Party, the factory nuclei, the students etc., the nature of the danger is perfectly clear. Not feeling themselves to be active participators in the general Party work, and not receiving an appropriate and timely response to their Party demands, considerable sections of the Party would begin to look round for a substitute for Party self-initiative in the form of groupings and fraction formations of every kind. It is precisely in this sense that we speak of the significance of such groupings, as the “Workers’ Group”.

But also at the opposite pole, the ruling one, there is a no less great danger represented by that policy which maintained itself too long and appeared before the consciousness of the Party as bureaucratism. It would be a ridiculous and undignified ostrich policy not to understand or not to remark, that the charge of bureaucratism formulated by the resolution of the C.C. is a charge directed precisely against the leading mainstays of the Party. It is not a mere question of single deviations of the Party practice from the proper ideal line, but of the very policy of the apparatus, its bureaucratic tendency. Does Bureaucratism involve the danger of a degeneration or not? It would be sheer blindness to deny this danger. Bureaucratization, during its long development, threatens to involve an estrangement from the masses, a concentration of the whole attention on the questions of administration, of selection and transfer of functionaries, a narrowing of outlook, a weakening of the revolutionary instinct, i.e. a greater or less opportunist degeneration of the older generation, at least of a considerable part of it. Such processes develop slowly and almost imperceptibility, but they are revealed with great suddenness. To regard such a warning based on objective Marxist foresight, as something like “an offence”, “a sudden attack” is only possible in the case of an unsound bureaucratic small-mindedness and an apparatus-like nature.

Is, however, the danger of such a degeneration really so great? The fact that the Party grasped or felt this danger and actively responded to it–one of the particular results of which was the resolution of the Political Bureau–witnesses to the deep-rooted vitality of the Party and thereby opens potent sources of antidotes against bureaucratic poisoning. Herein lies the chief guarantee for revolutionary self-maintenance of the Party. But as far as the old policy tried to maintain itself at any cost, by means of pressure, of increasing artificial selection, of intimidation, shortly by means of methods based on bureaucratic mistrust of the Party, so far the real danger of a considerable part of the Party mainstays becoming degenerated would unavoidably have ensued. The Party cannot live exclusively on the capital of its past. It suffices, that the past has prepared the present. But it is necessary that the present stand ideologically and practically on the same level as the past, in order to prepare the future. The task of the present is: to transfer the centre of gravity of the Party activity to the basic strata of the Party.

It might be said that such a kind of transference of the centre of gravity is not accomplished at once, by means of a leap: the Party cannot “stow away in the archives” the older generation and at once begin to live in a new style. It is hardly worth the while to waste any time on such a silly demagogical insinuation. Only fools could speak of stowing away the older generation in the archives. It is a question of the older generation consciously modifying the policy, and precisely by this means securing its further leading influence on the whole work of the self-acting Party. The older generation must regard the new policy, not as a manoeuvre, not as a diplomatic treatment, not as a temporary concession, but as a new stage in the political development of the Party. Then the leading generation as well as the Party as a whole will reap the very greatest advantage.

III. The Social Composition of the Party.

The question, of course, is not limited to the mutual relation of the generations. In a larger historical sense, the question is decided by the social composition of the Party, and, in the first place, by the specific weight within it of the factory nuclei and the proletarians from the benches.

The first task of the class which seized power, was the formation of the state apparatus, including the army, the organs of economic administration etc. But to staff the apparatus of the state, of the co-operatives, etc. with workers, unavoidably involved the weakening and the emasculation of the fundamental factory nuclei of the Party and an extraordinary growth within the Party of the administrative elements, both of proletarian and of other origin. The only possible way of escape is by means of substantial economic successes, by means of a healthy pulsation of the life in the factories and by means of a permanent influx into the Party of workers remaining at the benches. At which tempo this fundamental process will proceed, what ebbs and flows it will have do undergo, all this is hard to predict.

It goes without saying, that also in the present stage of our economic development, everything must be done in order to attract to the Party as many workers from the bench as possible. But a profound modification of the Party membership extending so far as, for instance, to render the factory nuclei two thirds of the Party, can only be obtained very slowly and only on the basis of very substantial economic successes. In any event we are obliged to reckon on a still very long period, during which the most experienced and active members of the Party–among them, of course, also those of proletarian origin–will be occupied in various positions in the apparatus of the State, of the trade unions, of the co-operatives, of the Party. And this fact in itself involves dangers and constitutes one of the sources of bureaucratism.

A totally unique place is and will be necessarily occupied in the Party by the schooling of the Youth. It is precisely by educating the new Soviet intelligenzia including a high percentage of Communists, by means of Workers’ Faculties, Party Universities, Higher Special Educational Institutions, that we withdraw young proletarian elements from the lathe not only for the period of schooling, but as a rule for the whole of their remaining life: the workers’ Youth having passed the Higher Schools, will, obviously, in due time, be absorbed in the apparatus of industry, of the state and of the very Party. There thus exists a second factor of destruction of the inner equilibrium of the Party to the detriment of the basic factory nuclei.

The question whether a Communist originates from a proletarian, intelligenzia or other stratum, is, of course, not without importance. In the first post-revolution period, the question of the pre-October profession seemed even a decisive one, because the transfer from the bench to this or that Soviet function presented itself as a temporary affair. At the present time, a radical modification has already taken place in this respect. There is no doubt, that the Presidents of the gouvernement executive committees or the Commissaries of divisions of the Army, constitute a certain social Soviet type, which to a considerable extent, is independent of the stratum, from which every single President of a gouvernement Executive Committee, or the Commissary of a division has come. During these six years, fairly stable permanent groupings of Soviet Society have formed themselves.

We are, consequently–and along with this, for a comparatively long period–confronted with such a position, in which a very considerable and best trained section of the Party is absorbed in various apparatuses of administration, economics and military command; another considerable section is studying; a third section is scattered throughout the villages, working in agriculture; and only the fourth section (numbering, at present, less than a 6th) consists of proletarians working at the bench. It is quite evident, that the growth of the Party apparatus, and the features of bureaucratization accompanying this growth, are not caused by the factory nuclei, which unite by means of the apparatus, but precisely by all the other functions of the Party which are carried out by it through the mediumship of the State apparatus of administration, economics, military command and education. In other words, the source of bureaucratism in the Party is the increasing transference of attention and forces towards the state apparatuses and institutions with an insufficiently rapid growth of industry.

In view of these underlying facts and tendencies we must take the more clearly into account the dangers of the apparatus-like degeneration of the old mainstays of the Party. It would be a crude fetishism to believe that the old mainstays, merely because they come from the best revolutionary school of the world, constitute in themselves a self-sufficing guarantee against each and every danger of ideological shallowing and opportunist degeneration. No! History is made by means of men, but men is by no means always consciously making history, not even his own. In the end, the question, of course, will be decided by the great factors of international importance: by the course of revolutionary development in Europe and by the tempo of our economic construction. But to impose fatalistically the whole responsibility upon these objective factors, is just as erroneous as to seek guarantees only in one’s own subjective radicalism inherited from the past.

It is perfectly obvious that the heterogeneity of the social composition of the Party created by the entire situation, does not weaken, but on the contrary, extremely sharpens all the negative sides of the apparatus policy. There is not and there cannot be any other means for over-coming the narrow craft and bureaucratic spirit of single portions of our Party, than their active approach to the regime of Party democracy. By supporting the “absolute tranquility”, by splitting everybody and everything, the Party bureaucratism hits equally hard, though in different manners, the factory nuclei, the economic functionaries, the military, and the studying Youth.

As we saw, in a particularly acute manner, there reacts against bureaucratism the studying Youth. It was not for nothing that Comrade Lenin proposed largely to attract the studying Youth for the fight against bureaucratism. By its composition and personal ties, the studying Youth reflects all the social strata contained in our Party and absorbs all their moods. By reason of its youthful sensibility, it is inclined immediately to impart an active form to all these moods. As a studying Youth it strives to explain and to generalize. This does not by any means signify that the Youth, in all its attitudes and moods, gives expression to sound tendencies. If this were so, this would mean: either, all is well in the Party, or the Youth would cease to reflect its Party. But neither the one, nor the other is the case.

To assert, that our foundations are not the nuclei of educational institutions, but the factory nuclei, is, as a principle, true. But when we say, that the Youth is the barometer, it is precisely by this that we impart to its political expressions not a fundamental, but a symptomatic significance. The barometer does not create the weather, it only indicates it. The political weather is created in the depths of the classes and in those spheres where the classes come into collision with one another. The factory nuclei create a direct and immediate connection of the Party with the class which is fundamental for us, with the industrial proletariat. The village nuclei in a far weaker degree form a connection with the peasantry. With the latter, in the first place, we are connected by our Army nuclei, which are, however, placed in quite definite conditions. Finally, the student Youth, recruited from all strata and intermediate strata of the Soviet society, reflects in its many-coloured composition all our virtues and defects, and we should be stubborn heads if we did not lend a most attentive ear to its moods. To this it must be still added, that a considerable portion of our new students consists of Party members with a revolutionary experience sufficiently serious for the young generation. And it is quite in vain that our most recalcitrant apparatus men now inveigh against the Youth. It is our indicator, it will take our places in the ranks, and the morrow belongs to it.

But let us return, however, to the question of the Party overcoming the heterogeneity of the single sections and groups of the Party which are divided by their Soviet functions. We said and we repeat it here again, that the bureaucratism in the Party is by no means a survival of a preceding period, on the contrary, this phenomenon is essentially new, deriving from the new tasks of the Party, from its new functions, from its new difficulties and its new faults.

The Communists within the Party and within the state apparatus are grouped in different ways. In the State apparatus they are in a hierarchic dependence one upon the other, and in complicated personal mutual relations with non-party people. Within the Party, they all have the same rights as regards the determination of the fundamental tasks and methods of the Party. The Communists work at the bench, they are members of factory councils, they administer enterprises, trusts, syndicates, they stand at the head of the Superior Council of National Economy, etc. As far as the economic administration by the Party is concerned, it takes into account–and it must take into account–the experience, the observation, the opinion of all its members on the various grades of the administrative-economic structure. The fundamental, incomparable superiority of our Party consists precisely in this, that it has at every moment the possibility, to look at industry with the eyes of a Communist working at the bench, of a Communist trade union member, of a Communist manager, of a Red Merchant, and by summing up the experiences, mutually complementing one another, of all these collaborators, to determine the line of its leadership of the economy in general and of certain branches of the latter in particular.

It is quite obvious that the Party leadership can only be carried out on the basis of a vital and active Party democracy. And vice versa, the more predominance is acquired by the apparatus-like methods, the more the leadership of our Party is substituted by the administration of its Executive organs. (Committees, offices, secretaries, etc.) We see how, with a strengthening of such a policy, all affairs are concentrated in the hands of a small group of people, sometimes even of one sole secretary, who appoints, recalls, gives directives, calls to account, etc. With such a degeneration of the leadership, the fundamental and most valuable superiority of the Party–its manifold collective experience–falls into the background. The leadership assumes a purely organizatory nature and degenerates, not infrequently, into a simple ukase and intimidation. The Party apparatus penetrates into all the continually more detailed tasks and questions of the Soviet apparatus, is absorbed with the daily cares of the latter, is exposed to its influence and ceases to see the wood for trees. If the Party organization, as a whole, is richer in experiences than any of the organs of the State apparatus, this can by no means be said regarding single functionaries of the Party apparatus. It would be indeed ingenuous to think that a secretary, merely on account of his being a secretary, embodies the total sum of the knowledge and abilities which are necessary for Party leadership. In fact, he creates for himself an appropriate apparatus with bureaucratic departments, with a bureaucratic information, with stereotyped replies, and by this apparatus which brings him nearer to the Soviet apparatus, he estranges himself from the living Party. And this proceeds just as expressed in the well-known German quotation: “You believe you are pushing, and you are being pushed yourself”. The whole many-sidedness of the bureaucratic every-day work of the Soviet State, penetrates into the Party apparatus and sets up in it a bureaucratic deviation. The Party, as a collective, does not feel its leadership, because it does not carry it out. From this there arises the discontent or the disagreement, even in those cases when the leadership is essentially right. But is cannot maintain itself on the right line so far as it spends itself on minor affaires and does not assume a systematic planned and collective nature. It is by this that bureaucratism not only destroys the inner consolidation of the Party, but also weakens its proper influence on the state apparatus. This is not in the least observed nor understood by those who scream the loudest regarding the leading role of the Party in relation to the Soviet State.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n16-feb-29-1924-inprecor.pdf