No country, perhaps, in the Western Hemisphere has been as blighted by U.S. intervention as Nicaragua. Already involved for over seventy-years at the time of this writing, a valuable synopsis of imperialism’s role up to the 1927 invasion.

‘Historical Background of the Nicaraguan Situation’ by G.A. Bosse from The Communist. Col. 6 No. 2. April, 1927.

THE historical background of the intervention of the United States in Nicaragua is very important for an understanding of the present situation because almost identically the same events have occurred there time after time. Also, the financial] history of the past 15 years is valuable for an understanding of the present situation, including as it does a series of treaty-loans, canal negotiations, etc.

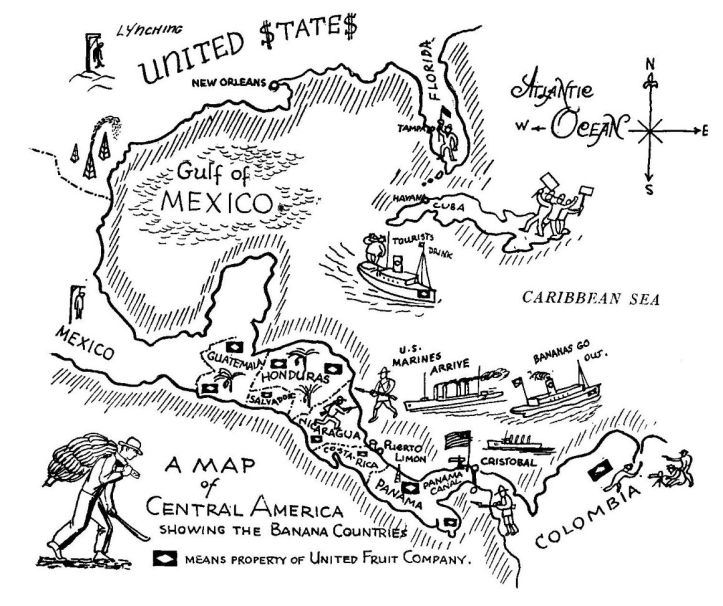

The significance of Nicaragua is twofold: financial and military. Militarily, the proposed canal through Nicaragua is very important, partly because it is more easily defended and partly because the Panama Canal is rapidly nearing its capacity, and a Nicaraguan canal will supplement it commercially. The United States could not afford, from a military point of view, to have any rival power to build a canal through Nicaragua, since the latter route is almost invulnerable from the sea. Aside from this twofold character of the situation in Nicaragua itself, there is a third, and far more important side, namely, the basis for an attack upon Mexico in an attempt to modify its oil and land laws.

Since 1856 no president has been permitted to hold office in Nicaragua against the wishes of American imperialism. In that year an American adventurer named Walker, shot his rival and became president. The U.S. pretended to be neutral, as at present; but 2,500 Americans participated in the revolution, and the American minister aided Walker. At that time Nicaragua was the route to the gold fields of California, and the slave-holding South, which was then faced with the coming Civil War, forced intervention. The greatest banker of the day, Vanderbilt, later crushed Walker, with the aid of the other four Central American States and the Nicaraguan Conservatives, because Walker and the American capitalists who backed him had excluded him.

Till 1893 the Conservatives ruled the country. Regular elections were never held. In that year there was a Liberal revolution, resulting from a dispute over spoils. Zelaya then ruled until] 1909, through a clever use of both Liberal and Conservatives. Zelaya introduced “prosperity” through widespread use of concessions to foreigners, which Nicaragua is now paying for. He became the leader of the Latin-American movement, encouraging revolutions as far away as Ecuador and Colombia, but was forced out by the United States when he opposed its policy of expansion.

In 1909 there was a revolution against Zelaya, led by Chamorro, Estrada and Diaz. The cause of it was a loan negotiated by Zelaya with European bankers against the protest of the U.S. government. Diaz was then a $1,000 a year clerk in the employment of an American company. This $1,000 per year clerk advanced $600,000 for the revolutionists which was later repaid. Estrada stated that American corporations had advanced $1,000,000 for the revolution. The American consul cabled the state department that a revolution would break out the next day and asked Washington to recognize the new government. Five days later he reported that a provincial government had been established with Estrada at its head, which was friendly to American interests. United Fruit Company steamers openly aided the rebels, with the assistance of the American government representative in Nicaragua.

When the Zelaya government executed two Americans who were caught attempting to dynamite a ship loaded with Zelaya’s troops, the U.S. broke off relations with Nicaragua, and dismissed its charge d’affaires at Washington. Zelaya was forced to flee the country and the U.S. continued to oppose his successor, Madriz, who was regularly elected by the Nicaraguan congress. It also broke through the government blockade with arms for the rebels and gave them control of the customs. American marines prevented Madriz from capturing Bluefields, where the rebels were, (exactly as again in 1926-27), and permitted the rebels to fly American flags on their ships as well as prevented the government from blockading any ports. With this aid from the U.S. the Conservative rebels defeated the government and forced Madriz to resign. They plundered the well-filled treasury (until then no loans from the United States had been necessary), inflated the currency, ruined industry and agriculture, and even assumed the debts of both sides. After this a series of loans was forced on Nicaragua by the U.S. in the natural course of events.

In 1910, the Dawson Pact was signed by the Estrada group and the U.S., whereby the U.S. recognized Nicaragua on the condition that Estrada be elected president and Diaz vice-president; also, provided that a loan from the American bankers would be arranged guaranteed by the customs revenues. The U.S. prevented a popular election, and the Conservative assembly carried out the above mentioned pact. In 1911, when the U.S. recognized the Estrada government, the Liberals exposed and published the pact. In April of the same year the assembly adopted a constitution guaranteeing the independence of the country and directed against foreign control through loans. Estrada dissolved it and called new elections. Protests and threats of revolution resulted in his resignation, and Diaz became president. The American minister wired Washington in May that the assembly would confirm Diaz in the presidency “according to any one of…the plans which the state department may indicate…A war vessel is necessary for the moral effect.” The warship was sent. D.G. Mufro, writing for the Carnegie Foundation for International Peace, writes that if Zelaya had won out, “…all of the efforts of the state department to place Nicaragua on her feet politically and financially would have been useless, and the interests of the New York bankers, who had undertaken their operations in the country at the express request of the U.S. government, would be seriously imperiled.”

In June, 1911, Secretary of State Knox signed an agreement with the Diaz government (Knox-Castrillo agreement) for a $15,000,000 loan from the American bankers, guaranteed by customs revenues and financial supervision by the United States. The bankers made up the list of customs officials, the U.S. okayed it, and Nicaragua selected its men from the list. It also established American bankers’ control of the National Railway. The U.S. senate refused three times to ratify this agreement and it fell through. In July, however, the American bankers signed an agreement with the Diaz government for a $1,500,000 loan, giving them 51% control of the National Bank, guaranteed by customs control and a lien on the liquor tax. They were also empowered to appeal to the U.S. to enforce the contract. Knox was to be the arbitrator between the bankers and Nicaragua. The American charge d’affaires kept the assembly in session until the agreement was approved.

When the new Nicaraguan constitution was adopted against the wishes of the U.S., the bankers disregarded it and the state department assisted them in loans which violated it. In 1912, the Liberals demanded an election, but the U.S. refused to permit until the new American-controlled National Bank was established. The Liberals started a revolution in July. The bankers demanded aid and in September marines were landed. Eight batt ships and 2,600 troops were sent there, the capital bombarded, the leader of the rebels defeated and exiled, and elections held under the supervision of the American marines. Diaz was re-elected for four years, and the expenses incurred in crushing the rebellion were repaid by Diaz to the U. S. through new loans guaranteed by the tobacco and liquor taxes.

In 1916, marines again manned the polls, and the Wall Street puppet was unanimously re-elected, although the U.S. minister admitted that the Liberals had the bulk of the population behind them. That same year the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty was signed giving the U.S. the right to build the Nicaraguan Canal, with a 198 year lease of a naval base in the Gulf of Fonseca and the islands in the Caribbean, off the mouth of the proposed canal. For this Nicaragua received three million dollars, which was to be applied to her debt to the U.S. This treaty practically made Nicaragua a protectorate. Costa Rica and Salvador, which border on the Gulf of Fonseca protested and were sustained on an appeal to the Central American Court of Justice. This court had been instituted by the U.S. as its special tool, but it was dissolved in 1918 when the U.S. instructed Nicaragua to refuse to abide by the decision.

In 1918, a High Commission was appointed to supervise the finances of the country, consisting of two Americans and one Nicaraguan. In 1920, the American bankers forced a nine million dollar loan on the country for the American-controlled railway. In 1923, during the centenary of the Monroe Doctrine, Secretary of State Hughes extended it, from non-interference of European powers in Latin-America, to the right of American interference at its leisure, “to make available its friendly assistance to promote stability in those of our sister republics which are specially afflicted with disturbed conditions.” He invoked the Panama Canal as the excuse, stating that its protection was “essential to our peace and security. We intend in all circumstances to safeguard the Panama Canal. We could not afford to take any different position with respect to any other waterway that might be built between the Atlantic and the Pacific” (a Nicaraguan canal). The London “Times” characterizes this as “whole-hearted imperialism” and showed its reflection in the recent actions (1926-27) of Kellogg.

In 1924, Nicaragua had bought back the Pacific Railways (also called the National Railway), and the National Bank, but American control of both continued through the Americans on the High Commission, those on the board of directors of the railway an the American commission to revise the banking laws of the country. In 1921, there had been another uprising, but great shipments of arms by the U.S. enabled the Conservative government of Chamorro to retain control, the marines enforcing martial law. In 1921, U.S. marines wrecked the offices of the Nicaraguan paper “Tribune.” In 1922, they killed a number of Nicaraguans. In August, 1925, they were withdrawn after 13 years of constant domination of the country, and a native constabulary trained and officered by Americans was substituted. In November, 1924, the Liberal, Salorzano, was elected president over Chamorro by 48,000 votes against 28,000. In January, 1925, Chamorro forced him to resign and became president. Early in 1926, Sacasa led a Liberal revolt against Chamorro and was exiled. The U.S. state department had declared Chamorro unconstitutionally made president, under the 1923 Washington treaties (which provided non-recognition of any president coming to power by armed means).

We thus see how the present situation is simply a culmination and repetition of what has been going on in Nicaragua for the last seventy-five years. While the bankers have controlled financial life of the country, the marines have controlled its political life.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v06n02-apr-1927-communist.pdf