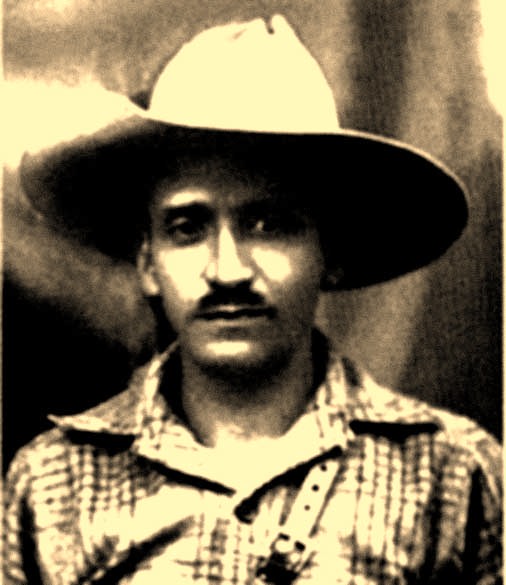

A rising against its imperialist-backed military dictatorship, led in part by the young Communist Party of El Salvador sees 10s of thousands killed in reprisals, including Farabundo Martí, La Matanza–The Massacre. The scale of the killings, particularly directed at the Nawat people, was not apparent at this writing.

‘The Uprising in Salvador’ by O. Rodriguez from The Communist. Vol. 11 No. 3. March, 1932.

THE heroic struggles of the workers and peasants of Salvador, under the leadership of the Communist Party, in the January uprising constitute a landmark in the development of the revolutionary upsurge in the Caribbean countries and in the whole of Latin America. All our Parties will have to study the lessons of these struggles in order to eliminate the weaknesses, as well as reinforce the strong sides of our movement, that have come to the surface in the Salvadorean uprising.

This uprising was a mass movement of toiling peasants and agricultural workers against the insufferable conditions cf the deepening crisis and of the white terror, against the intolerable oppression of the native landlords and capitalists in alliance with foreign imperialism. It demonstrated a tremendous accumulation of revolutionary energy, readiness to struggle and self-sacrifice on the part of wide masses of workers and toiling peasants under the banners of the Communist Party, the rapid growth of the revolutionary upsurge among the masses which, in varying degrees, is the present characteristic of all the Caribbean countries. The poorly armed—practically unarmed—masses held their ground for over a week against the combined forces of the government, the armed fascist bands of the “golden” youth of the native and foreign exploiters, and warships and marines of Yankee and British imperialism. Despite these tremendous odds, the masses ay held such cities as La Libertad, Sonsonate, Ahuchapan and many smaller towns, centering in the important coffee region of the country, spreading throughout the entire Pacific coast and seriously threatening the capital of Salvador. The uprising showed the deep sympathies for the revolutionary struggles of the masses that are diffused among the rank and file of the army which, on various occasions, had refused to fire upon the insurgents.

The workers and peasants of Salvador, led by the Communist Party, have written an undying and glorious chapter in the history of the world revolutionary movement. With their lives and blood they have proven to the struggling masses everywhere that on the next and higher stage of struggle, with a stronger Communist Party and more powerful revolutionary unions and Peasant Leagues that will be created in the course of the daily fight for the immediate demands of the workers and peasants, and by the application of Leninist principles and tactics, the victory must and will belong to the masses.

Directed by the diplomatic representatives of foreign imperialism in San Salvador, and supported by the Yankee, British and Canadian warships and marines, the government of Maximiliano Martinez has crushed the January uprising of the workers and peasants, killing and wounding between 500 and 2000 people. The government in alliance with the imperialists has unchained the wildest white terror carrying through daily mass executions of all “suspected” of participation or even sympathy with the uprising. With especial bestiality the white terror is raging around the Communist Party, the revolutionary unions and Peasant Leagues. This mad white terror is rapidly spreading to the other Caribbean countries, especially Guatemala and Honduras, in a desperate effort to check the growth of the revolutionary upsurge and as a measure of war preparations under the hegemony of foreign (chiefly, Yankee) imperialism. It is the task of the Communist Parties in the Caribbean countries to mobilize the widest masses of employed and unemployed workers, toiling peasants, and all sincere anti-imperialist elements, for a determined struggle against the white terror, especially in Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, against the general offensive of imperialism and its native supporters (wage cuts, unemployment, etc.), against the imperialist robber war on China and for the defense of the Chinese revolution and the Soviet Union. The struggle against the white terror is an essential part of our anti-war campaign.

***

The lack of complete information prevents us at this time from making a complete evaluation of the struggles and lessons of the January uprising in Salvador. But a beginning along these lines can and must be made already now, especially since the Manifesto of the Communist Party of Salvador (published in the Bulletin of the C.P. of Honduras, January 1, 1932) indicates the approach of the comrades to the general character of the uprising.

This Manifesto, which must have appeared shortly before the outbreak of the struggles, suffers from a number of basic defects. These defects are, in our opinion, as follows:

1. The Manifesto does not formulate the partial economic and some basic political demands of the masses. There is no mention in it of the 8-hour day, the minimum wage, unemployment relief and insurance, social insurance generally, etc., which are the basic partial demands of the agricultural and industrial workers; while such demands as the right of the workers and toiling peasants to organize, to freedom of press and assembly, etc., are handled in the Manifesto in a negative way by merely demanding the “abolition of the August 12 and October 30 decrees.” Nor is there any mention in the Manifesto of such partial demands of the toiling peasants as immediate relief from starvation, the abolition of taxation, the cancellation of indebtedness, the abolition of forced labor and other services to the landlords, etc. Nor are there any partial demands for the improvement of the conditions of the rank and file of the Army.

2. The Manifesto does not call upon the masses for any concrete action (strikes, mass meetings, demonstrations, etc.). One cannot tell from the Manifesto what methods of struggle the Party calls upon the masses to adopt immediately and what methods of struggle will become inevitable in the higher phases of the struggle.

3. The Manifesto does not propose to the masses any definite and concrete forms of organization for the carrying on of the struggle. On this point, as well as on the question of methods of struggle, the Manifesto contains neither slogans of action (Committees of Action, Revolutionary Peasant Committees, Joint Worker-Peasant Committees of Action), nor propaganda slogans (Soviets). ‘The basic task of organizing Workers’ and Peasants’ Defense Corps is also absent from the Manifesto.

4. The basic demands of the agrarian anti-imperialist revolution are not stated with sufficient clearness, especially the anti-imperialist demands (confiscation of all imperialist enterprises, cancellation of foreign debts, withdrawal of all armed and other forces of foreign imperialism, etc.).

These basic defects of the Manifesto clearly show a non-Leninist approach to the task of unfolding the counter-offensive of the Salvadorean workers and peasants against the offensive of the exploiters—by ignoring some of the basic partial demands of the masses, by failing to formulate clear slogans of action on the methods of mass struggle and forms of organization and to link up the slogans of action with our propaganda slogans, pointing out the inevitable course of the development of the struggle, to limit the scope of the mass movement, to isolate the revolutionary vanguard from the basic mass of the workers and toiling peasants, jumping over those phases of the struggle in which the masses become mature for the passing over to a higher stage, and failing to provide for the creation of revolutionary organs of mass struggle, under communist leadership, without which the movement could not successfully rise to a higher phase of development. The actual course of the January events, the fact that the fight began with the highest form of revolutionary mass struggle (uprising) without the previous development and organization of the daily struggles of the masses through strikes, demonstrations, hunger marchers, etc., demonstrates the same basic weaknesses as those contained in the Manifesto. These weaknesses are the result of the opportunist tendencies in our midst that have a “left” sectarian, a putchist approach to the tasks of the Communist Party. One of the chief lessons of the Salvadorean uprising is the great danger of putchist and “left” sectarian tendencies against which we must wage the most energetic struggle at the same time carrying on a merciless fight against the Right opportunism—the main danger in the present period—which hesitates to place the Party at the head of the masses in their struggles against the landlord-bourgeois-imperialist offensive.

Only by combatting ruthlessly the putchist variety of opportunism—that variety which ignores the objective conditions, refusing to apply the Leninist method of analysis of the relation of class forces, making its own impatience a guide to action for the Communist Party—can we carry on a successful fight against the Right variety of opportunism whose “objective analyses” reflect the pressure of the ideology of the bourgeoisie and the social fascists upon the toiling masses.

The workers and peasants of Salvador, under the leadership of the Communist Party, will continue with redoubled energy the fight against the offensive of the exploiters, learning from the defeat how best to prepare the fight for the coming victory. Our comrades must bend all their efforts to maintain the closest possible contact with the masses and to prosecute with the greatest energy the task of organizing and leading the daily struggles of the workers and peasants for the improvement of their conditions. The utmost attention must be paid to the task of developing methods of illegal work under the present conditions of terror, to protect the Party organization from the mad onslaught of the enemy, at the same time utilizing even the smallest possibilities for legal mass work, fighting for such possibilities, combining the illegal with the legal work and concentrating our activities on the plantations, haciendas and factories.

At the time when the workers and peasants of Salvador are facing the combined ruthless offensive of foreign imperialism and the native oppressors, the Communist Party of Salvador will continue to demonstrate to the masses that it is the only Party able and willing to organize and lead their struggles against the native and foreign exploiters.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v11n03-mar-1932-communist.pdf