Padmore begins his 1937 Crisis series on East Africa with a look at the history of French, Italian, and British imperialisms attempts at conquering what is today’s Ethiopia

‘Abyssinia–The Last of Free Africa’ by George Padmore from The Crisis. Vol. 44 No. 5. May, 1937.

“The people of Abyssinia are anxious to do right…but throughout their history they have seldom met with foreigners who did not desire to possess themselves of Abyssinian territory and to destroy their independence.”–Emperor Haile Selassie in a note to the League of Nations, dated June 9, 1926.

BEFORE discussing the political circumstances which made it possible for Italy to launch her barbarous attack upon Abyssinia, it is necessary to review the historical relations of this ancient African kingdom with Western Europe. Such a background is essential for a clear understanding of how it came about that England, France, the so-called defenders and champions of “Collective Security,” betrayed this country to a Fascist power. The answer is that Abyssinia, as we shall show, has always been a pawn in European diplomacy, and as such, has been sacrificed in the interests of Imperialism.

Italy Turns to Abyssinia

Although Abyssinia had had contact with Europe as early as the sixteenth century, when the Portuguese came to her aid in her struggle against Islamic invaders, it was only during the ‘nineties of the last century, when the great European Powers were scrambling for territories in Africa, that the West began to take a great interest in Abyssinia.

It was during this period that Italy, thwarted in her first attempt to obtain a footing in North Africa, thanks to the annexation of Tunis by France, turned towards Abyssinia.

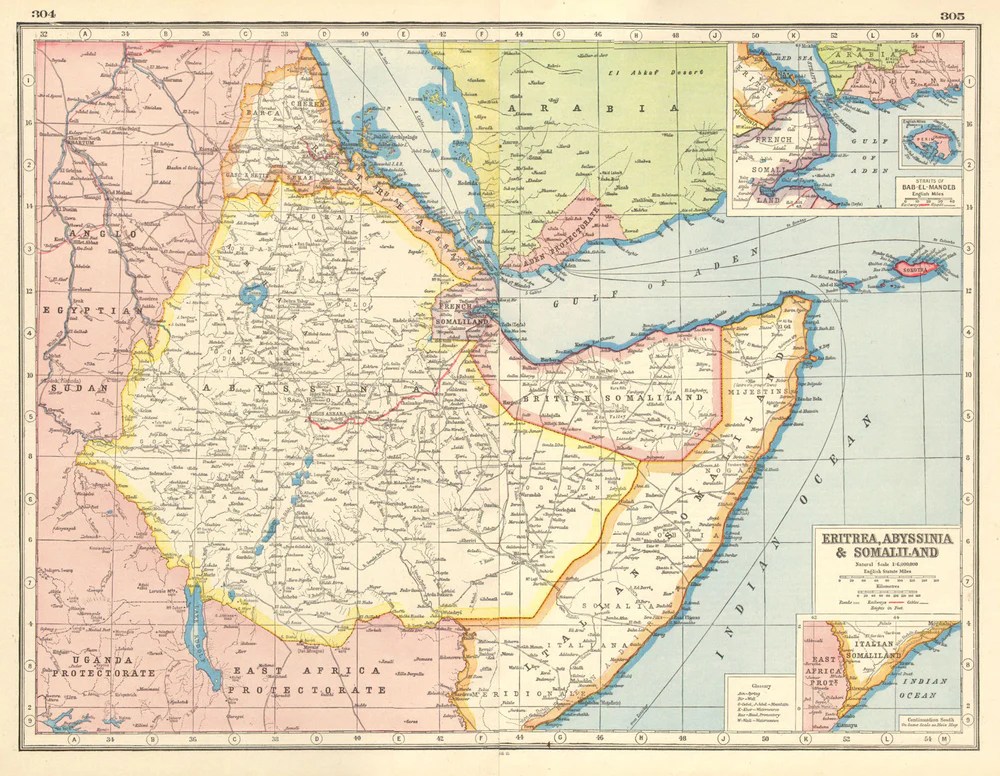

The Italians first established themselves at Assab on the Red Sea. Later on, encouraged by England, at that time the bitter colonial rival of France, Italy began to set up garrisons at various points along the coast north of Assab, in order to prevent France from extending her influence along the Red Sea. In 1885 Massowa was annexed, and within two years the whole Eritrean littoral was under Italian occupation.

Utilising these bases as points of departure, the Italians gradually began to push inland, finally coming into conflict with the Abyssinians, who at that time occupied the hinterland of Eritrea. This attempt of the Italians to annex Abyssinian territory met with defeat when an Italian garrison was slaughtered by the Tigreans, at Dogali, in January, 1887. Defeated in their first attempt to get a foothold in Abyssinia proper, the Italians, without abandoning their designs, turned their attention southwards and established a protectorate over the territory now known as Italian Somaliland. There they entrenched themselves, waiting for a favourable opportunity to begin again leave off in 1887. Two years later such from where they had been forced to an opportunity presented itself.

In that year, Menelik, Ras of Shoa, Negisti (King of Kings) of Ethiopia was plotting to make himself Negus after the death of the Emperor Johannes, who had been killed in the war against the Dervishes. This brought about a dynastic quarrel between the Shoas and the Tigreans. In order to win the favour of Menelik, the Italian government offered to support his cause against Ras Mangosha, the illegitimate son of Johannes. The Italians supplied Menelik’s army with five thousand rifles, in return for which Menelik signed a convention, known as the Treaty of Ucciali, on May 2, 1889, granting the Italians extensive territorial concessions in Eritrea, which later became an Italian colony.

In Article 17 of the Amharic version of the treaty, Menelik stated that “His of the treaty, Menelik stated that “His Majesty the King of Kings of Ethiopia, may, if he desires to, avail himself of the Government of His Majesty the King of Italy for any negotiations he may enter into with the other Powers may enter into with the other Powers or Governments.” But in the Italian version, the words “may, if he desires to,” were changed to read, that the Emperor “consents to avail himself,” etc. The Italian government in the meantime informed the English, French, German and Russian governments that Menelik was under obligation to use their good office in any diplomatic dealings with them.

When Menelik heard of this duplicity on the part of his erstwhile Italian allies, he became so indignant that he denounced the convention as a fraudulent attempt on the part of the Italians to establish a protectorate over his country. And in a note to Umbarto, King of Italy, he wrote: “When I made that treaty of friendship with Italy, in order that our secrets be guarded and that our undertaking should not be spoiled, I said that because of friendship, our affairs in Europe might be carried on with the aid of the Sovereign of Italy, but I have not made any treaty which obliges me to do so, and today, I am not the man to accept it. That one independent power does not seek the aid of another to carry on its affairs your Majesty understands very well.”

Now it must be clearly understood that Italy was not acting alone in these underhanded attempts against the black monarch. She had the approval and full support of Britain, for at that time Italy was on bad terms with France because of her opposition to Italian imperialist expansion in North Africa. England on her part supported Italy in her designs upon Abyssinia because she was hostile to France’s colonial ambitions, especially in the Nile valley. Britain therefore hoped to use Italy against France in furthering her plans in the Sudan, while at the same time assuring the Abyssinians with whom she had made an alliance against the Dervishes in 1884, that she entertained no unfriendly designs upon their country. After having used the Abyssinians as pawns in suppressing the Dervishes, who, flushed with victory over General Gordon at Khartoum in 1885, were overrunning the Sudan, England then dropped her black allies and began to scheme openly with the Italians against Abyssinia. Accordingly, England signed three agreements with Italy, defining their respective spheres of influence in Abyssinia. The first of these agreements was signed between the Marquis Dufferin and Arva for England and the Marquis di Rudini on behalf of Italy on March 24, 1891; the second was made a month later, on April 15, in Rome; and the third on May 5, 1894, between Sir Francis Clare Ford, British Ambassador in Rome, and Crispi.

“Vilest Treachery”

By the terms of these treaties which were naturally kept secret from Menelik, Italy agreed to allow Britain to secure a highland route through Abyssinia for her Cape to Cairo railway, the dream of Cecil Rhodes, and further assured England that the waters of the Atbara would not be interfered with. England on her part agreed to allow Italy to annex the remainder of Abyssinia and pledged her support of the occupation of Kassala whenever she (Italy) desired to make such a move against Menelik, Commenting upon Britain’s perfidy, A.B. Wylde, Her Britannic Majesty’s Consul General for the Red Sea, in his book, Modern Abyssinia, writes: “Look at our behaviour to King Johannes from any point of view, and it will not show one ray of honesty, and to my mind, it is one of our worst bits of business out of the many we have been guilty of in Africa….England made use of King Johannes as long as he was of any service, and then threw him over to the tender mercies of Italy, who went to Massowa under our auspices with the intention of taking territory that belonged to our ally, and to allow them to destroy and break all the promises England had solemnly made to King Johannes after he had faithfully carried out his part of the agreement. The fact is not known to the British public, and I wish it were not true for our credit’s sake; but unfortunately it is, and it reads like one of the vilest bits of treachery that has ever been perpetrated in Africa.

After the revocation of the Treaty of Ucciali, the Italian government began to adopt a policy of bullying Menelik into acceptance of Italy’s protection. But the Emperor refused to be coerced. Events then began to move with great rapidity. Crispi, assured of the support of England, as well as Germany, to which country Italy became attached as a member of the Triple Alliance in 1882, decided to use force against Menelik.

Since Italy’s European enemy was France, Menelik turned to that country for support. Furthermore, France was opposed to the Anglo-Italian agreements referred to above, which she considered as obstacles to her imperial aspirations in the Nile valley. For this reason she was bent on breaking them up, so as to humiliate Italy further in Africa and thereby weaken the Triple Alliance in Europe. Her first gesture towards Abyssinia was to refuse to recognize Italy’s claim for a protectorate over that country. The French government later on sent a military mission to Abyssinia to train Menelik’s warriors. France also supplied the Emperor with arms and ammunition to defend his country against Italy. But this was no altruistic affair. France, having gained the sympathy of Menelik, the Emperor granted a concession to a French company, La Compagnie Imperiale des Chemins de Fer Ethiopiens, to construct the Jibuti-Addis Ababa railway, thus laying the basis for French economic penetration into this part of Africa.

Italy Strikes But Loses

The Italians, led by General Baldisserra, launched the attack in 1896, but were completely routed. More than six thousand were killed in the battle of Adowa, while more than two were taken prisoners, including two generals. Crispi expected aid from England, but as she always intended to use Italy and not to be used by her, the British government refused to help pull Italy’s chestnuts out of the Ethiopian fire. In great indignation the Italian statesman protested to the Central Powers, accusing Britain of downright treachery. The expression “Perfidious Albion” was as frequently on the lips of Italians then as today. Italy also expected aid from the Central Powers. Commenting upon the bitterness of the Italians towards their allies, Baron Patti, the Austrian Ambassador in Rome, in a despatch to his government, cynically remarked, “I have already had to listen to Italian lamentations, in every key, that they have been the victims of the Triple Alliance.” But despite all Crispi’s wailings and appeals, none of Italy’s tardy allies came to her rescue. Under these circumstances, the Italian government was compelled to pay Menelik an indemnity of two million dollars and recognise the independence of his country. Double-crossed by their friends and defeated by their enemies, all that was left for the Italians to do was to abandon for the time being the hope of colonial expansion in this part of Africa.

Ethiopia’s prestige went up overnight. Menelik, the first black ruler to defeat a great white power, became the subject of discussion in every chancellory of Europe. All of the great powers were now jostling each other to win the favour of the Conquering Lion of Judah. Britain sent a mission to Abyssinia headed by Sir Rennell Rodd. France appointed one of her leading diplomats, M. Leonce Legarde, Governor of Jibuti, her minister at Addis Ababa. The Czar also sent special emissaries to the court of Menelik. The Russians became such favourites of the Emperor that some were commissioned as officers in his army. Even the Italians were not to be left out. With their tails between their legs, a delegation headed by Frederico Ciccodicolo came trying to ingratiate themselves into the favour of their conqueror.

We have more or less indicated the aims and objects of the three Western Powers in Abyssinia, namely, to impose their hegemony over the country. But what was the reason for the Czar’s interest in Abyssinia? For Russia had never been an African power. The answer is revealed in the German secret documents dealing with this period, which disclose that had Italy succeeded at Adowa, Russia had planned to intervene, in order to establish a naval base on the Red Sea as a threat to Britain’s route to India and the Far East. This plan had the support of France, and would certainly have brought about a war with England. In this respect Menelik certainly did Europe a good turn by licking Italy and postponing a world war for nearly two decades. Such were the political repercussions in Europe after the first Italo-Abyssinian war.

The terms of peace were embodied in the Treaty of Addis Ababa, signed in October, 1896. From now on the contest for the black pawn was between England and France.

England and France try

Between 1896 and 1905, imperialist conflicts over Africa were sharpened on all fronts–extending from Fashoda to Morocco. Italy having been eliminated by a knockout blow in the first grab at the pawn, England was now faced with a new political situation. She no longer had an ally. For the first time the British imperialists were thrown upon their own resources in a major contest. Faced with an unavoidable necessity, the British government decided to act as quickly as possible, in order to forestall the French in the Nile valley. With this object in view, the Foreign Office instructed Lord Cromer that Kitchener, then Commander-in-Chief of the Egyptian Army–for England had been in occupation of Egypt since 1882–was to move into the Sudan and reoccupy Dongola, then under Turkish sovereignty. About the same time, France, free of all effective opposition against her from within the frontiers of Abyssinia, also decided to strike out for the Sudan. Two French expeditions were despatched on this mission, one force starting in the West from the French Congo, under Major Jean Baptiste Marchand; the other starting east from the Abyssinian plateau, under Captain Clochette. forces were to make a convergent movement with Fashoda as their junction.

The Menelik, still grateful for the aid which France had rendered him, and distrustful of England, the friend of his old rival, Italy, supplied several hundred warriors to the French eastern expeditionary force. On July 10, 1898, two years after the western column commenced its march, Marchand arrived at Fashoda on the Nile and planted the Tricolour. The other column never arrived. In the meanwhile, the British force under Kitchener desired to replace the Tricolour with the Union Jack, but the intrepid Marchand resisted. Finally a compromise was reached by hoisting the Egyptian flag, against which neither side could take objection, as England and France had always subscribed to the fiction that Egypt was independent. Thanks to this maneuver, both officers “saved face.” made their bows to each other, after which Kitchener retired. But behind this façade of military courtesy, the diplomats at Downing Street and the Quai d’Orsay were waging a veritable battle of words over Fashoda. National chauvinism led by the Daily Mail, swept over Britain and soon England and France were on the verge of war. Lord Salisbury demanded the recall of Marchand.

Finally, Delcasse, the then Foreign Minister of France, decided to give way in order not to alienate the support of England against Germany in the war of revenge which was the great obsession of French foreign policy–the recovery of Alsace and Lorraine. Marchand was instructed to retire. The gallant soldier returned to Paris, where he was proclaimed a national hero.

Britain, having won a decisive victory in the struggle for the headwaters of the Nile, established herself as the undisputed mistress of the Sudan. But soon she began to realize that her intransigent attitude on the colonial front–against France in Africa, and Russia in Asia–had placed her in a position of complete isolation on the continent, where the system of alliances–the Triple Alliance on the one hand, and the Dual Entente on the other had come into being. Without a friend in Europe, hated and despised in Asia and Africa, Britain, through Chamberlain, turned first to Germany and when Germany turned down her offer of an alliance, she began to make overtures to France, which were the prelude to that “entente” which the German diplomats had considered impossible.

While still distrustful of England, Delcasse nevertheless welcomed this opportunity of settling outstanding differences between his country and Britain, which laid the basis for the Entente Cordiale in 1904. The most significant of these agreements was the convention settling disputes between the two powers in Newfoundland, West and Central Africa and the New Hebrides in the South Seas; there was also a declaration concerning Siam and Madagascar; but most important of all was the bargain regarding Egypt and Morocco. France also came to terms with Italy by agreeing to let her filch the North African territories of Turkey, in return for her support against Germany. Such were some of the intrigues of secret diplomacy involving Africa in the course of the struggle to grab the grand prize–Abyssinia.

The three Western Powers–England, France and Italy–having at last arrived at an agreement over the sharing up of North Africa–Morocco for the French, Egypt for the British, Libya for the Italians–were now able to concert together over Abyssinia. Just as Italy had been eliminated in this tripartite contest over her defeat at Adowa, Russia, who had also been playing for high stakes at Menelik’s court, now found herself in the same position. Discredited through her defeat by Japan in 1905, her European rivals could now afford to eliminate her as a party to this impending imperialist deal. So with the Asiatic Bear out of the way, the three occidental wolves drew up an agreement in 1906 outlining their respective spheres of interest in Abyssinia.

Terms of tripartite agreement

In this way Abyssinia was once more drawn into the orbit of European diplomacy. What were the terms of this agreement? The preamble states: “It, being the common interests of France, Great Britain and Italy to maintain intact the integrity of Ethiopia, to provide for every kind of disturbance in the political conditions of the Ethiopian Empire, to come to a mutual understanding in regard to their attitude in the event of any change in the situation arising in Ethiopia…” The document then proceeds to define the interests of the three contracting parties as follows: “First, the interests of Great Britain and Egypt in the Nile Basin, more especially as regards the regulation of the waters of that river and its tributaries…without prejudice to Italian interests mentioned in paragraph (2); second, the interests of Italy in Ethiopia (Abyssinia) as regards Eritrea and Somaliland (including the Benadir), more especially with reference to the hinterland of her possessions and the territorial connections between them to the west of Addis Ababa; third, the interests of France as regards the French protectorate on the Somali coast, the hinterland of this protectorate, and the zone necessary for the construction and working of the Jibuti-Addis Ababa and working of the Jibuti-Addis Ababa railway.”

In plain language, these three Powers simply agreed to divide Abyssinia as they had done North Africa as soon as the change in the status quo of the country favoured such a move. And to add insult to injury, the conspirators had the audacity to present a copy of their bargain to Menelik, who thanked them for their courtesy. The old man, having laid the basis of his Empire, passed away in 1913, leaving his throne to his grandson, Lij Yasu, who was later deposed by his Christian subjects, led by Emperor Haile Selassie, then known as Ras Tafari, who is the son of Ras Makonnen, Menelik’s cousin, and hereditary Governor of Harar. He was also Governor of Harar before he became Regent in 1928. On the death of the Empress Zaudity, daughter of Menelik, Haile Selassie was crowned Negus Negisti in 1930. This brings us to the end of the second phase of the conspiracy of the West against this ancient kingdom.

When the World War broke out, Italy deserted her allies and adopted a position of neutrality. In 1915 she decided to join the Allied Powers, in return for a share in the colonial swag. According to the terms of the London Agreement of 1915, England and France promised that in the event of either Power increasing its colonial territory in Africa at the expense of Germany, those two Powers “agree in principle that Italy may claim some equitable compensation, particularly as regards the settlement in her favour of the questions relating to the frontiers of the Italian colonies of Eritrea, Somaliland and Libya, and the neighbouring colonies belonging to France and Great Britain.”

While it is true that this secret treaty made no direct reference to Abyssinia, the failure on the part of the Allied Powers to carry out their promise to Italy was bound to affect Abyssinia, the only African territory not yet annexed, and as such a standing invitation to predatory capitalism, especially Fascism, the more ravenous manifestation of post-war Imperialism. Disappointed by the settlement of the Paris Peace Conference, Italy immediately turned her attention towards Africa, and in 1929 proposed a plan to England for mutual support in obtaining concessions in Abyssinia. Briefly, the following was the basis of the proposals: First, “In view of the predominating interests of Great Britain in respect of the control of the water of Lake Esana, Italy would support Great Britain’s claim to construct a barrage on Lake Tsana ‘within the Italian sphere of influence,’ as defined in the Three Power Agreement of 1906; second, Italy would also support with the Abyssinian Government the British claim to construct and maintain a motor road between Lake Tsana and the Sudan; third, in return, Great Britain should support the Italian claim to construct and to run a railway from the frontier of Eritrea to the frontier of Italian Somaliland, running through Abyssinia to the West of Addis Ababa; and fourth, Italy would also claim an exclusive economic influence in the west of Ethiopia, and in the whole of the territory to be crossed by the above-mentioned railway. This claim also to be supported by Great Britain.”

Italy being on particularly bad terms with Jugoslavia, as well as her ally France, desired to keep Paris out of the new bargain. Britain, however, declined to accept the proposals of Italy, for at that time she was in direct negotiations with the Abyssinian government and had reason to believe that she would obtain the necessary concessions to build a dam on Lake Tsana, in order to regulate the supplies of water of the Nile for the cotton plantations in the Sudan. They were, however, disappointed. The Abyssinian government refused to accept the British proposals. Instead Haile Selassie turned toward America, where negotiations were opened with the White Engineering Company of New York for constructing a barrage on Lake Tsana. In making In making this decision, the Emperor was no doubt influenced by the fact that America, because of her geographical position, would be less likely to have annexation designs upon Abyssinia than the great European Powers. Furthermore, the anti-imperialist sentiments expressed by President Wilson in 1919 might also have created the impression among the Abyssinians that they could expect a squarer deal from Americans than Europeans.

The imperialists fall out

Italy, peeved by Britain’s refusal to make a secret deal with her behind the back of France, began to draw closer towards Abyssinia in the hope of ingratiating herself into the favour of Haile Selassie. In order to implement this gesture of friendship, Italy encouraged Abyssinia to become a member of the League of Nations in 1923. In his letter of application to the League, the Emperor wrote: “The Holy Scriptures bear witness that since the year 1500 after Solomon we have been contending with the heathen–by whom (as may be seen from the map of our country) we are surrounded–for the faith and the laws of God, and to maintain the independence of our country and the freedom of our religion. We know that the League of Nations guarantees the independence and territorial integrity of all the nations of the world, and maintains peace and agreement among them; that all its efforts are directed towards the strengthening of friendship among the races of mankind; that it is anxious to remove all the obstacles to that friendship which give rise to war when one country is offended; that it causes truth and loyalty to be respected.”

England, scenting the game Italy was up to, placed herself in opposition to Abyssinia’s entry into the League. Embittered because the blacks had refused to grant them the concession to dam the waters of Lake Tsana, the British imperialists felt that it might be necessary sooner or later to exert direct pressure upon the Emperor, and Abyssinia’s presence at Geneva would be embarrassing to them. But thanks to the support of Italy and France, who were then desperately trying to increase their prestige in Addis Ababa at England’s expense, Abyssinia was admitted into the League in September, 1923. Two years later, Britain, whose prestige had fallen considerably by this time, decided to exert direct pressure upon Abyssinia. Let us see how the crafty Britishers went about it.

They first settled outstanding accounts with Italy by granting her Jibuland in 1924, a strip of territory covering an area of about 33,000 square miles in East Africa. In this way an Anglo-Italian rapprochement was concluded. Then Sir Austen Chamberlain, the Foreign Secretary, addressed a note to Mussolini, through Sir Ronald Graham, the British Ambassador in Rome, asking the Duce to support Britain’s efforts in getting control of Lake Tsana. In return England promised Mussolini “to recognize an exclusive Italian economic influence in the West of Abyssinia.” The British government also agreed to support Italy in all her demands in all those parts of Africa which fell within her sphere of interest. And as was to be expected, Mussolini And as was to be expected, Mussolini was jubilant. At last, the proud Britons, who had declined Italy’s advances in 1919, fell within the Fascist grip! Chamberlain’s proposals on all points, The Duce replied offering to accept “especially sharing the desire of the British government to realise the principle of friendly co-operation and trusting, moreover, that this principle may be continually further extended for the protection and development of the respective Italian and British interests in Ethiopia, naturally on the basis and within the limits of the provisions of the London Agreement of 1906.”

The two governments, having secretly agreed to bring pressure to bear upon their victim, decided upon the next step. Both Powers despatched letters to the Abyssinian government, intimating what they had decided upon. What a shameful affair! A so-called democratic statesman conspiring with Mussolini, the arch enemy of democracy, to rob a weak and defenseless people of their liberty. Replying to the note of these two gentlemen, Haile Selassie wrote: “The fact that you have come to an agreement, and the fact that you have thought it necessary to give us a joint notification of that agreement, makes it clear that your intention is to exert pressure, and this, in our view, at once raises a previous question. This question, which calls for preliminary examination, must therefore be laid before the League of Nations.”

France, having been excluded from the agreement between England and Italy, was highly indignant and supported Abyssinia’s protest to the League of Nations against this dastardly attempt to infringe upon the sovereignty of a member State. Faced with this exposure, the Italian and British governments hurried to assure the Abyssinians that they had no territorial designs upon their country. They were just simply exchanging harmless notes a la methode diplomatique. Abyssinia accepted the assurances of her enemies and the matter was allowed to drop at this stage.

Baldwin plays a lone hand

Britain then began to play a lone hand once more. Accordingly, she tried to allay the justifiable suspicions of the Abyssinians by offering them an outlet to the sea through the port of Zeila in British Somaliland. The Abyssinians, however, declined this gesture. Zeila has always been the bait of the British Foreign Office, a sop which they dangled from time to time before the Abyssinians. Italy, seeing the game Britain was playing, also began to make overtures to Abyssinia. In order to disarm the Abyssinians, by giving them a false sense of security, Mussolini signed a treaty of friendship and arbitration with Haile Selassie in August, 1928, the most important clause of undertake to submit to a procedure of which affirmed that “Both governments conciliation and arbitration disputes which may arise between them, and which it may not have been possible to settle by ordinary diplomatic methods, without having recourse to armed force. Notes shall be exchanged by common agreement between the two governments regarding the manner of appointing arbitrators.”

Had this treaty been respected by Mussolini when the Wal-Wal incident occurred in 1934, the war which later occurred would have been avoided. But Mussolini never had any intention of honouring his signature. The treaty was simply a diplomatic mask behind which he was able to prepare his plans of aggression while at the same time creating the impression among the Abyssinians that Italy had abandoned her traditional imperialist designs against this country.

We shall once more turn our attention from Africa to the European scene, and make a cursory review of events which occurred on the continent between 1933 and 1935. For it was these happenings which made it possible for Mussolini to steal the Abyssinian pawn away from England. The drama which opened in Berlin ended in Addis Ababa. The emergence of Fascism in Germany in 1933 had a tremendous effect upon the whole European situation. Overnight, as it were, the whole international situation changed, bringing about a realignment of forces. Faced with the threat of war from across the Rhine, France turned towards Italy for assistance against Germany, and as a quid pro quo agreed to relinquish her interests in Abyssinia and support Italy in grabbing the long fought-for pawn from England.

From this moment, Abyssinia’s independence was doomed. For Haile Selassie, having placed the destinies of his country in the hands of the League of Nations was in a less favourable position to maneuver than Menelik in 1896. Had there been no League of Nations, Abyssinia would have stood a better chance of escaping from the clutches of Italy by pursuing her traditional policy of playing off one Power against another. Instead of looking to Geneva for protection, she would have given more attention to her military defence. Furthermore, the dilly-dallying tactics of the League facilitated Italy’s preparations, while leaving Abyssinia exposed to her enemy.

The diplomatic stage having been set by the Pact of Rome, signed on January 7, 1935, the Duce at once proceeded with his military preparations, which culminated in Italy’s invasion of Abyssinia in October, 1935.

We shall later on deal with the final phase of this great betrayal and examine the role played by Britain, France and the League of Nations, the custodians of “Collective Security” and the rights of small nations.

The next installment, which will appear in the June issue, will be entitled “Abyssinia Betrayed by the League of Nations.”

The Crisis A Record of the Darker Races was founded by W. E. B. Du Bois in 1910 as the magazine of the newly formed National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. By the end of the decade circulation had reached 100,000. The Crisis’s hosted writers such as William Stanley Braithwaite, Charles Chesnutt, Countee Cullen, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, Angelina W. Grimke, Langston Hughes, Georgia Douglas Johnson, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Arthur Schomburg, Jean Toomer, and Walter White.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/sim_crisis_the-crisis_1937-05_44_5/sim_crisis_the-crisis_1937-05_44_5.pdf