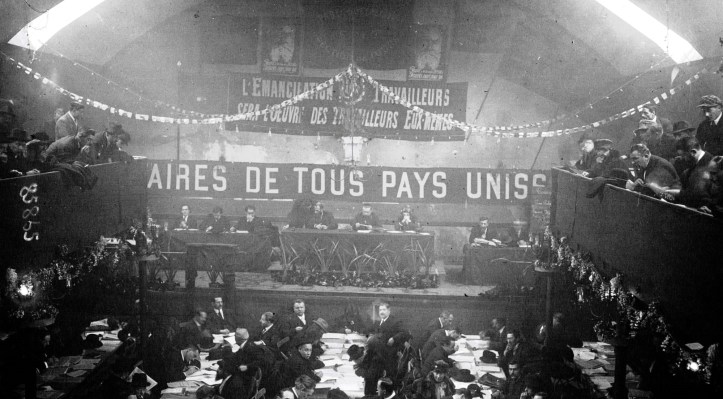

Much of the early Communist movement was a negotiation with syndicalism, the other mass revolutionary working class tendency of the time, with both the U.S. party and International receiving many of its initial core cadre from the movement. With a number of different syndicalisms and vastly different national experiences, the debates can be murky from this many years distance. Swiss militant Jules Humbert-Droz, here a Comintern emissary, does not hide his bias, but still offers a very useful summary of the organizations, personnel, and ideas as they stood in France at this time.

‘The Syndicalists and Communists in France’ by Jules Humbert-Dróz from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 2 No. 9. January 31, 1922.

The following article is an excerpt from the article which appeared in the Russian issue of the central organ of the Red Trade Union International “Krasnyi International Profsoyuzov” of the 15th of December, 1921. In view of Comrade Humbert-Droz’ position as a secretary of the Communist International, his description and opinion of French conditions are of special interest. The Editors.

The question of the relations between the Communist Party and the revolutionary trade-union movement is everywhere, and particularly in France, one of the most important problems of the revolutionary movement. In order to realize the unity and Successful cooperation of all Communist and revolutionary elements in France, we must necessarily take into consideration and even partly accept the traditions of the past. The Communist Party of France is young, and since its Congress at Tours which was to mark the beginning of the new era of the reawakening of the labor movement, it has not quite realized the hopes of the revolutionaries. It was not able to free itself entirely of the influence of the reformist party of Jaurès, Renaudel and Longuet. It has indeed accomplished a great deal in the organization and propaganda fields; but it fell short in political achievements. The party executive was completely preoccupied in organization and administrative matters and did not perform its function as a leading political organ.

It is true that the leaders of the C.G.T., who are at the helm until this very day, were compelled at the Congress of Lille to give up their plans of expelling the revolutionary trade-unionists. The are doing their best, however, to effect a split and are gradually expelling all the revolutionary trade-unionists.

Under these circumstances the revolutionary minority faces the danger of dissolution and the scattering of its forces. This danger is so much the more real because since the unsuccessful strike of 1920, the great masses have left the C.G.T. and there remained in the organization only the really tried workers.

Those elements which are united in the Revolutionary Syndicalists Committees (C.S.R.) are carrying on the struggle against reformism in the spirit of the pre-war revolutionary syndicalist traditions of the C.G.T.

It is true that the Syndicalists are conscious of the fact that due to the far-reaching historical events of recent years, revolutionary thought and tactics require greater clearness and precision, but up till now they are only united by the fundamentally negative program of fighting against Jouhaux, Merrheim and reformism.

Thus the weak spot of the minority is the lack of creative revolutionary ideas and of a practical program, and should the federation minority become a majority tomorrow, it would find that the various conflicts within its own ranks would paralyze every attempt at constructive work.

In the C.S.R. we can name four divisions. Anarchists, “pure” Syndicalists, Spartacists, Communists and Party-Communists who are for the subordination of the trade-unions to the party. While the Anarchists have at present become outspoken counter-revolutionaries, the “pure” Syndicalists, i.e., the former Anarcho-Syndicalists, cannot as yet overcome the magic power of the old and stultified ideas of the Amiens Charter and are still denying all revolutionary significance to the Communist Party.

The Syndicalists-Communists who have gathered about their weekly organ “La Vie Ouvrière” and who are at the head of the intellectual revolutionary opposition, are sincere revolutionists, who have modified their position under the pressure of social development, and who have even formulated their principles in the spirit of the Communist International, but who nevertheless have not yet had the courage to renounce all the logical conclusions to be drawn from their revision of the old Syndicalist doctrine. Finally, as far as the Party-Communists are concerned, I think that some of them, Loriot and Tommasi for instance, have wrongly interpreted the attitude of the Executive in this matter, and have sought to spread the false idea that it was the party’s duty to subordinate the trade-unions to itself. The only effects of this attempt were to strengthen the Anarchists and the Anarcho-Syndicalists; they have also brought conflicts into the ranks of the Syndicalist-Communists.

While the party sought to act as an “impartial” judge in the midst of these struggles and various tendencies, the members of the party actually joined the various divisions, and some members even followed Jouhaux. The leaders of the pure Syndicalist camp belong to the party. And it was and still is the duty and obligation of the party to take a clear and unequivocal position in this fight. The party must fight for the Communist-Syndicalist Party, but it must on the other hand ruthlessly and energetically fight all other tendencies. There can be no room in the party for Majoritaires and “pure” Syndicalists; neither can if possibly insist upon the subordination of the trade-unions. In France the formulas of “Subordination” and “Independence” of the trade-union movement have assumed an absolute character. The Communist International has never demanded or approved the subordination of the trade-unions in any country. All that the Communist International demanded was that every Communist Party should promulgate the idea of Communism in the trade-unions and that the Communists should remain and be active within the trade-unions as disciplined Communists. We were always of the opinion that the party could gain the confidence of the working-class and a greater influence in the trade-unions, only through hard work and propaganda. This influence is a question of confidence and in no way a question of power. We believe that in France as well as in any other country this propaganda work could be accomplished by means of small committees and Communist groups within the trade-union movement. This poorly-understood and wrongly interpreted idea, indeed the very word “group-formation”, has become the bugbear which all our opponents parade against us.

As we have pointed out above, the position of the Syndicalists in all the big problems of the Social Revolution coincides with our own positions. While in conversation and in discussions with French comrades like Monatte, Monmousseau and others, I have had the opportunity of convincing myself that in all these questions there is not the slightest difference of opinion between us.

We therefore ask these comrades in the name of our common cause that they not only give expression to their ideas among their followers, but that they present and discuss them clearly and openly as their new platform and that they give them the widest publicity.

It goes without saying that this mutual relationship between the Party and Revolutionary Syndicalism can in no way be based upon the subordination of one to the other. For the solution of the problem it does not suffice to lay down the organic independence of the trade-unions as a principle, for every revolutionist must realize the necessity of coordinating and uniting all the revolutionary forces against the united bourgeoisie. The Syndicalist comrades have repeatedly pointed out in their organ “La Vie Ouvrière” the necessity of cooperating with the Communist Party. On the question of the part to be played by the Communist Party in the Social Revolution, however, there is great confusion in the ranks of the Syndicalist-Communists.

Among them are some who actually think the party to be the private property of a few politicians and journalists. On the other hand there are those who take no account whatever of the Communist Party as a revolutionary factor; according to them this question remains to be answered by Revolutionary Syndicalism. Indeed, the very existence of the Communist Party fills them with fear lest in the future they find in it their “Competitors”. In reality, however, Monatte’s idea is the old idea of the Syndicalist doctrine, namely, that of an “active minority (minorité agissante) which leads the organized trade-union workers with it into the revolutionary struggles. Monatte is convinced that if Syndicalism is to adopt itself to the problems of the Social Revolution, it must assume the form and character of a political party, without confining itself to the organization of the working masses who are only striving to improve their working and living conditions. In such a case Syndicalism would undoubtedly become a political party which would be based upon the support of the organized trade-union workers. And with eyes wide open, Monatte still thinks that such a competition between the two parties, i.e., between the Communist and Revolutionary-Syndicalist parties, would only benefit revolutionary development.

Of course, this idea needs no criticism. The existence of two Communist parties would become the source of painful conflicts which the working-class would not understand. Monatte also makes a mistake when he thinks that the uniting of all revolutionary workers into the Syndicalist Party would be such an easy matter. The fundamental question of the dictatorship of the proletariat, alone would cause the Syndicalists and Anarcho- Syndicalists to secede from the Syndicalist Party. According to Monatte’s friend, Monmousseau, a “division of labor” is necessary in the revolutionary preparatory work; namely, while the Syndicalists are preparing the proletariat for the revolution, the Communists are to carry on propaganda among the intellectuals and peasants.

Of course, the Communist Party cannot be satisfied with the part that Monmousseau assigns to it; according to its nature it must remain a proletarian party. On the other hand, this division of tasks proposes a joint leadership and the unity of two organizations. The only solution of the problem consists in the following: that all the Communist-Syndicalists should join the Communist Party, whereby they renounce the attitude that Syndicalism alone can lead the revolution to a successful finish. Among the Communist-Syndicalists, it is Rosmer who came to this very conclusion. Of course, his old friends are fighting against his attitude, which shows that their prejudice against anything political decides the issue for them. But the real revolutionists must be able to free themselves of all prejudices. This particular prejudice is based upon the fact that in the past year the party has not fulfilled their cherished hopes. But the Communist-Syndicalists should take just the opposite view and consider it their duty to cooperate in the transformation of this young party into an organ of the revolutionary struggle, which is to launch its activities in coordination with the autonomous trade-unions and to join them in the fight against reformism and the various forms of Anarchism.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1922/v02n009-jan-31-1922-inprecor.pdf