As the conflict in West Virginia neared its culmination in the Battle of Blair Mountain, another Battle of Matewan, less famous than Sid Hatfield’s stand there a year earlier, was fought in the summer of 1921 as a three-day fight between union miners and the militia and gun thugs was fought over the Tug River.

‘Bullets, Babies, and Scab Coal’ by Helen Augur from The Toiler. No. 174. June 4, 1921.

Matewan, W. Va. Yesterday I saw a little white iron bed in Blackberry City. A machine gun bullet from a Kentucky coal mine had crossed the Tug River, pierced three. stout walls and zig-zagged across the baby’s bed on its way through the house. The feathers from the little pillow straggled across the torn sheet. The wall behind bore an irregular design of holes.

Eight days before the baby had been snatched from that bed and carried to safety with her brothers and sisters, peltered with shots from highpowered rifles and machine guns, falling almost as thick as the heavy raindrops. The family were only that day crawling back from a rude shelter behind the hill, taking. a chance of more bullets, to save the children from pneumonia.

In the living-room, wrecked as if by an earthquake, the mother was sweeping up great heaps of splintered glass and wood. The mantlepiece mirror was gone, but the deep holes were there to stay. The family pictures were despoiled, books bored through and dishes smashed.

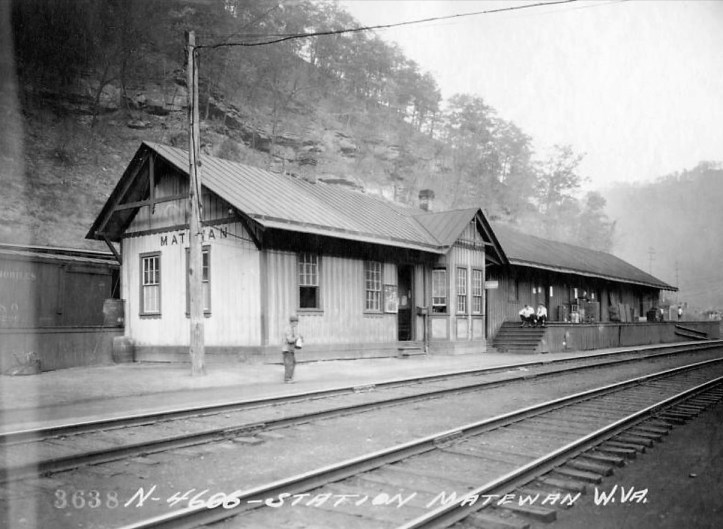

We had seen the father, John Ward, down the track toward Matewan. He is a railroad section foreman, The war in Mingo County is between the miners and the coal operators, and the railroaders are no party to the dispute. Yet here was the baby’s bed, and the wrecked home. And along the whole bluffside were the other pretty frame cottages, most of them not the property of the miners, riddled through and through with hundreds of bullets.

Back of the houses lay the brown canvas tents of the striking miners. There were two babies in the Stafford tent sick with pneumonia from exposure, and another in the Jackson tent. For two weeks no mother in Blackberry had gone to bed expecting to finish the night there. Sniping from the Allburn coal mine had driven them to cold cellars in their nightclothes.

Thirty bullets had made their easy way through the White tent.

Mrs. White, wan with days and nights over a piece of sheet-iron cooking for the fugitives, showed us her black winter coat hanging on the centerpole of the tent, under a severed electric light wire. It was riddled.

“Nev’ mind, I had two winters’ wear out’n it, anyway,” she said, triumphantly. “But when we crawled back here last night to get our clothes off and have a little rest, I told my husband I was going to sleep t’other way of the bed. Look where the bullets tore open the pillows. H’t made me right nervous.” She looked at the rifle under the bed. “I’ll swear they ain’t going to do this any more. I’m tired of it. I was raised in Carolina, where they ain’t no war like this, but ef they start again, I’m going to put my four least ones in a cellar, and help the men shoot.”

Silky blind rabbits, born during the battle, snuggled in the sunshine outside. Almost every other living thing on the bare hill had been mowed down the miners’ cows, and even their rose bushes. But now, after five days’ unwonted silence, the ground-hogs were venturing out of their holes, and the children were perching again on the fenceposts. Many of the families had not dared to come back, and their devastated houses peered sightlessly for them.

George Tindsley and his wife were tired. For a solid week before the three-day battle they hadn’t had their clothes off because of the night shooting. The chimney and the kitchen range had been considered safe places to crouch, until shots from highpowered rifles had sent bricks tumbling from the chimney, they and five small children and grandchildren had spent the nights in their cellar until they found it insecure. After that it was “over the hill.”

“I was washing clothes Thursday noon, when the machine guns opened on us,” said Mrs. Tindsley. “My son came running down the hilltop. They had aimed at him and one of the state constabulary up there. We ran down to the stone cellar of the milkhouse below the hill, with the thunder and bullets crack-cracking around us. In a space eight by ten feet there were nineteen children and seven grownfolks, and we had to stay there in the drenching rain for two days and nights. We had no food or water, any of us, for 36 hours. Then we ran down Sulphur Hollow, and a colored man and his wife took in these families.

“We wasn’t so bad off as some. Rob Moore’s wife had to get her little baby and her paralyzed mother out of the house. They stumbled into a ditch of water, and lay there, nobody knows how long. My oldest son was threatened that day by mine guards, and his married sister got him on a train just in time. We was awful afraid they’d do him like Clarence.”

Their 17-year-old son, Clarence, was shot in the back and killed by Baldwin-Felts detectives in the Matewan shooting a year ago. He was carrying no arms.

We crossed the village to the bluff’s edge. Across at Allburn little cars of coal were rounding the mountain–scab coal. On the plateau before the powerhouse a company of Kentucky militia were drilling. The sun beat down on their hot uniforms and their rifles cracked faintly to our ears. The strikers, squinting along the holes in the porchposts, sighted out the positions from which three machine guns had poured terror from the green Kentucky mountains.

We went down the steep road toward Matewan. High from a hillside came the song of a little girl rocking her doll to sleep. There was a bullet hole through its leg.

The Toiler was a significant regional, later national, newspaper of the early Communist movement published weekly between 1919 and 1921. It grew out of the Socialist Party’s ‘The Ohio Socialist’, leading paper of the Party’s left wing and northern Ohio’s militant IWW base and became the national voice of the forces that would become The Communist Labor Party. The Toiler was first published in Cleveland, Ohio, its volume number continuing on from The Ohio Socialist, in the fall of 1919 as the paper of the Communist Labor Party of Ohio. The Toiler moved to New York City in early 1920 and with its union focus served as the labor paper of the CLP and the legal Workers Party of America. Editors included Elmer Allison and James P Cannon. The original English language and/or US publication of key texts of the international revolutionary movement are prominent features of the Toiler. In January 1922, The Toiler merged with The Workers Council to form The Worker, becoming the Communist Party’s main paper continuing as The Daily Worker in January, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/thetoiler/n174-jun-04-1921-Toil-nyplmf.pdf