A country with class-collaboration melded into it at its origins see the rise of militancy, the growth of industrial unions, and a (near) general strike in 1913-4. Tom Barker, a central figure in those events, tells how it happened and gives us a history of New Zealand labor in the process. Barker was a self-educated, working-class Marxist, a leading figure in the New Zealand and Australian I.W.W., deported to Latin America for his anti-war and union activities, where he worked the Buenos Aires docks and became a leader of the international marine workers organizing and delegate to the Red International of Labor Unions.

‘New Zealand General Strike’ by Tom Barker from Voice of the People (New Orleans). Vol. 3 No. 14. April 2, 1914.

For many years New Zealand has been looked upon by the outside world as a social laboratory and from the utterances of social reformers, and articles in inspired publications, one would almost believe that in this country, there would be no problem of Capital and Labor, no unemployment question, no slums, etc. For years benevolent legislation has been doled out to the workers, and effected its purpose by rapping the backbone, and militancy of the organizations; and resulted in a tame, and emasculated union movement.

But, however, even the much praised Arbitration and Conciliation Act has now become a thing to be despised, and if possible rejected.

The first event of any far reaching importance in New Zealand was the great Maritime Strike which covered for a considerable period, the greater part of Australasia. This revolt took place in 1890, and although the strike was unsuccessful and the lash of victimization plied harshly by the employers, yet the workers through this struggle began to see the enormous possibilities of class unionism, and social action.

The unions paralyzed in the struggle soon began to reorganize, evidently on militant lines, for no sooner did the shrewder employers see their renewed danger than the much vaunted A. and C. Act made its appearance on the statute book. This Act was brought in ostensibly to foster unionism, increase wages, and better working conditions. The old idea of a clear-cut struggle between employer and employee became relegated to the past, while the new idea of a good case to ticket the cars of a $4000 a year Judge became the fashion.

Smal craft unions sprang up all over the country, which rapidly developed the meal ticket artist, and conservative union official.

These organizations became popular with the employers, as they fostered sectionalism, and thus the Arbitration Act, brought about a lickspittle, sniffling bosses unionism, which is just about as useless as total disorganization.

The A. and C. Act has served its purpose, and for 15 long years New Zealand earned the title of “the land without strikes.”

It is rather amusing to note that in the early days of the Act, many of the more conservative and ignorant employers fought against its mandates strenuously, and nowadays, after noting for twenty years its effect on militant unionism, praise it, and if necessary will compel obedience to its orders at the point of the bayonet, or the bludgeon of a Cow Country Cossack.

However, some of the more militant unionists shaking themselves from the lethargy of this demoralizing influence began a campaign against the Act, and its influences. The bulk of this propaganda was carried on by the Miners’ Unions, who especially in the West Coast of the South Island, have Australasian reputation for solidarity and militancy.

The first battles of any importances were two strikes on the Tramways in Auckland, where the men adopting militant tactics completely defeated the Tramway Company in 1907 and 1908.

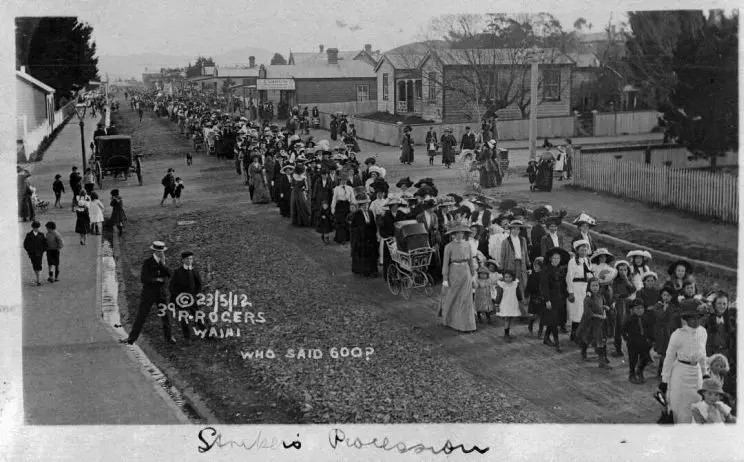

A few minor strikes took place in the meantime, and then came the great Waihi Strike in 1912; from which date began a State brutality and legalized murder, which sought to drive into peonage and subserviency, the proletariats of New Zealand.

Waihi is a gold mining locality situated nearly 140 miles from Auckland, in the midst of the Ohinemuri Hills, and at this place some 1200 miners battled for gold in one of the richest regions of the earth.

For many years the Union had been under the Arbitration Act, and conditions had become intolerable owing to the competitive contract system which is a cut throat system at its best.

The Union tired of the foul conditions and inadequate pay, ballotted, and cancelled their registration under the Act, after which by economic power they forced the Company to inaugurate the co-operative contract system or better known as “all in the job.” From that time conditions improved and good wages began to come to hand. Of course this did not please the gold mining people, and like the capitalist class the world over they were not particular as to the means they employed in bringing about the overthrow of the Miners’ Union.

Under the Arbitration Act any fifteen men can form a union, and apply for an award before the Court. The Court has then the power to extend this award as a Dominion Award, and make the award granted a Union of fifteen Miners cover the whole of the Miners’ Union of New Zealand.

Thus it can be seen how 15 men can be bribed into accepting an award that will reduce the wages and foul the conditions of 15,000 men.

The Waihi Coy got together some of their creatures, some 30 engine drivers to form a scab union, outside of the Miners’ Union and under the A. and C. Act. The miners promptly refused to be lowered by scab engine drivers and the great strike started May, 1912. The capitalist presses, (probably the most unscrupulous of its kind in the world) began to howl, that this strike was a fight between two sets of workers and not between the employers and miners. However, the 30 engine drivers were but a small minority of the engine drivers employed, and most of them were connected with various secret societies in which some slaves get a golden opportunity to meet and mix with the boss. The strike went on for three months, after which the Massey Government sent down a large army of 60 police. Some 65 unionists were arrested on the most specious charges and incarcerated in Mt. Eden Gaol at Auckland. The fight was fought on the old craft union principle, lasted 27 weeks, after which the militants were driven out of their homes by thugs and bullies armed with steel batons and revolvers. Hundreds of roughs, and ignorant half savage Maoris, were gathered together, given whiskey in a prohibited area, armed and turned loose on men, women and children. The scabs then attacked the union hall where one unionist, F.G. Evans was killed by a policeman and a scab, who clubbed him to death. Many other atrocities were perpetrated under the righteous cloak of law and order.

The mine was started with scab labor, the Waihi men were scattered far and wide. The strike lasted some six months and between $15,000 and $16,000 was subscribed by Australiasism Unionists to their comrades in Waihi.

But during this fight such was the power of the lying press in New Zealand that the great majority of the Arbitration Unionists turned down the Waihi Miners in their hour of trouble, and behaved as only boss-loving unions can by scabbing on their fellows left and right.

This great battle showed once more the utter futility of sectional unionism and action. The Labor Party with their organizer Walter Thomas Mills carried on a vigorous campaign against the Waihi men and helped in a thousand ways to overthrow them.

During the last few years much I.W.W. and militant unionist literature has been circulating in New Zealand and it has had a far reaching effect.

A national organization, the N.Z.F.L. had grown up in recent years, consisting largely of miners and waterside workers, which taught class organization, but practiced sectional action. The Waihi strike was followed by a debauch at Limaru, at which port, the watersiders were thrashed and victimized by the employers, while the national organization scabbed on them. In the meantime, an outside craft organization, the Slaughtermen, were also defeated. Then there was a defeat in the coal mines of Blackball, and a miserable compromise for the Stockton miners. A large unity congress was held in July, 1913, which resulted in a double wing outfit, a national Industrial Organization, the United Federation of Labor, and a political organization, the Social Democratic Party.

Early in 1912, an I.W.W. movement sprang into being in Auckland, and began propagating the General Strike Sabotage, and Industrial Unionism. Although small in numbers, it became very active, and soon the employers began to howl for the Government to deport this American abomination. A monthly paper was started “the Industrial Unionist,” which began to have a wide influence; literature was published and imported; and many meetings held.

A mental revolution had been working in the year 1913, in the minds of the toilers, the employers during this period had become overbearing and tyrannical in their attitude towards labor. All at once the arbitration doped workers roused themselves from the slumber of 20 years, and there began a gigantic rebellion, the like of which has never been seen before in the Isles of Australasia.

In the middle of October, 1913, the coal miners of Huntly struck against the systematic victimization of militant Union men. Their employers “the Tampiri Coal Company,” whose managing director is E.W. Alison (the Otis of New Zealand) had, by the same methods adopted in Waihi, engineered and financed a scab, union, under the Arbitration Act, some time previously.

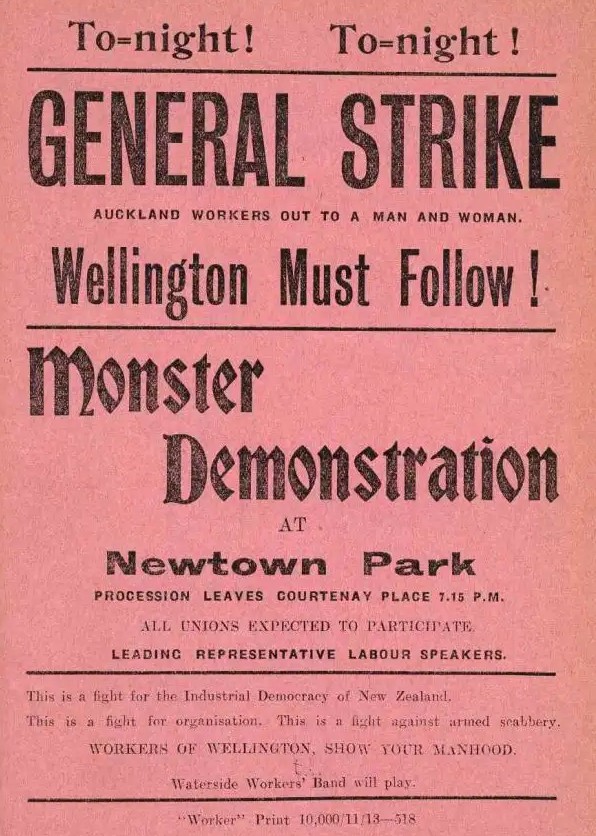

Immediately the Denniston Miners’ Union on the West coast of the South Island, held a meeting expressing common interest with the miners of Huntly and wired to the other coal miners in New Zealand, asking for a general strike. While this was happening in the South Island, the shipwrights in the port of Wellington were deprived of their traveling allowance by their employers, the Union Steamship Company, a great inter-colonial octopus with enormous interests and powers. The shipwrights were in the Waterside Workers’ Union, 18,000 strong, and to deal with their grievance, a stop work meeting was held. After the meeting was over the men returned to their ships to find that many of their places were filled. Another meeting was held and on October 22nd, the Waterside Workers went on strike. The Auckland Waterside Workers stopped working coal, on the Tuesday following so as to help the Huntly Miners, and cargo on the following day.

Inside of a week the Coal Miners of Huntley, Hikurangi, Seddonville, Stockton, Millerton, Denniston. Blackball, Paperoa, Runanga, Kaitangata and Nightcaps were closed down. The Brunner mine was forcibly stopped by contingents of mines from Blackbal and Runaga, who marched on the place. The Waterside Workers at Wellington, New Plymouth. Napier, Auckland and Onehunga stopped work in the North Island and those at Nelson, Picton, Greymouth, Westport, Pt. Chalmers, Dunedin, Jamaru and Lyttleton in the South Island made common cause in a splendid manner.

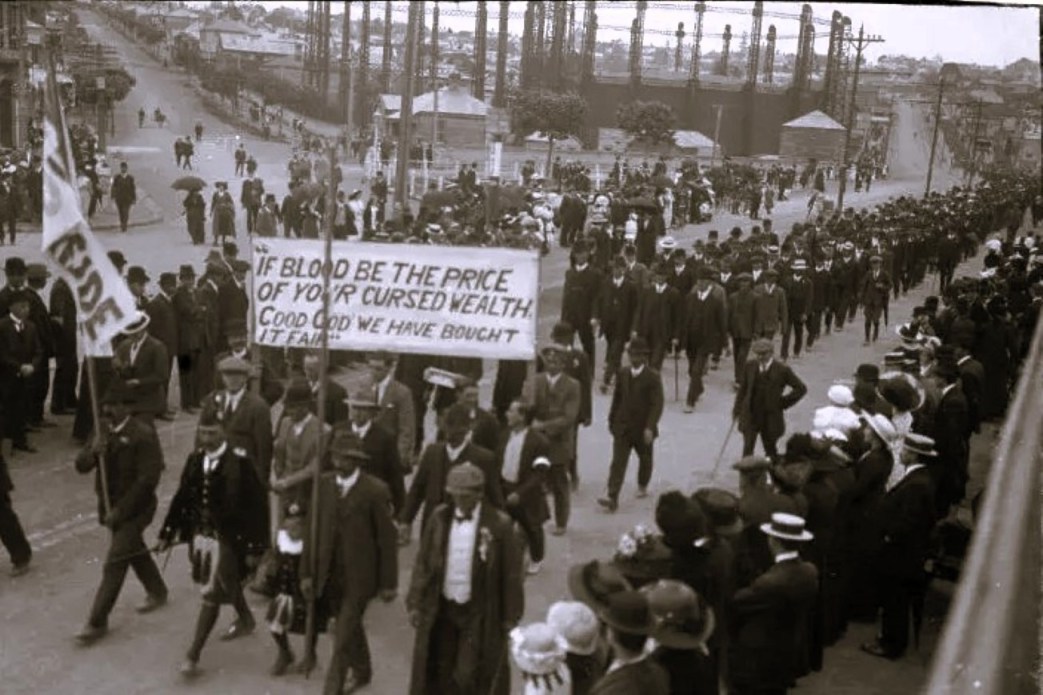

In Auckland a general strike was declared, and 26 of the largest unions tied Auckland up. Large meetings of 10,000 to 20,000 were held in Auckland, Christchurch and Wellington; enormous processions and splendid enthusiasm were the main features.

Then in stepped Iron Heel Massey, the Cowyard Premier, who had graduated from the shippons of Pukekohe, and with the executive of the Farmers’ Union, called on the country districts for special constables, mounted and armed with yard long bludgeons. They were mobilized quickly, and marched in their thousands into the towns.

As they marched in to load and protect their (?) property, the seamen disregarding their scabby officials sprang ashore, and left thousands of tons of shipping lying in the harbors.

The ships were loaded by scabs who drifted in, the usual riff raff, slum element, once the scab police had taken possession of the wharves. The tramway service in Auckland was tied up for 17 days, and then the men worked the ears on scab coal.

The Auckland Exhibition, a kind of a parody exhibition, should have started in December, but owing to the strike the main exhibits arrived too late. It is known as the White Elephant, and is a great financial loss to those financially interested.

In New Zealand, the farmer is a difficult problem to deal with, for owing to his isolated position, his ignorance is appalling, and therefore he can be easily played upon by the press, which is owned and controlled by the Big Business people.

Therefore, as soon as Fat wailed forth his lamentations, Henry Hayseed left his mortgaged section and came into the towns, to bludgeon the workers back to the folds of the Arbitration Act, and law and order.

These special constables performed many thrilling charges down the main street, and it became a criminal offense to shout “scab,” or even be in the same street.

However they forced open the Auckland and Wellington wharves, and then scab labor was introduced and slowly ships were loaded and unloaded. Then the cockroach business man and his ilk went stoking the ships, while the whole practically of the engineers and officers went scabbing also.

In November, the police arrested W.Y. Young, president U.F. Labor; Pat Fraser, secretary, S.D.P.; Harry Holland, Editor “Maoriland Worker;” Robert Semple, organizer U.F. Labor, and George Bailey, member of Wellington Strike Committee at Wellington on charges of sedition and inciting to resist.

Tom Barker, organizer I.W.W. was arrested on the day following, at Auckland on a charge of sedition, and remanded to Wellington on bail.

Bail was refused at the Wellington Court in the following week. Young was subsequently sentenced to three months for inciting, but the sentence was withheld pending an appeal, he was remanded for trial to the Supreme Court on the sedition charge. Bailey and Fraser were bound over to keep the peace in sureties amounting to $1500 each. Holland’s inciting case was dismissed, but he is on bail for the Supreme Court on two charges of sedition. Semple was bound over to keep the peace to the total of $3000 and fined $100 at Auckland for using seditious language. Barker had a charge of sedition, and one of inciting withdrawn, but was bound over to keep the peace to the tune of $3000, which was obtained after he had been in gaol nine weeks.

In the middle of December, Ed. Hunter, Denniston Miners, (Billy Banjo) were arrested and charged with sedition and remanded on bail to the Supreme Court, and also bound over to keep the peace for six weeks.

Tim Armstrong, West Coast Workers’ Union, was also bound over to keep the peace.

After a glorious fight, the strike was declared off just before Christmas, although the leaders part in doing so has caused considerable comment.

The whole strike was not only remarkable as a revolt against arbitration and foul conditions, but also as a rebellion against cast-iron officialism in both the labor unions and the parent organization. The general idea is that it will cost the employers and the State some $7,500,000 in losses.

The strike was marked by bad generalship, and muddle-headed incompetency by the officials, but a bright spot was the splendid response made by the unions. All the bright side of the fight was the attitude and solidarity of the rank and file who spontaneously rose to battle, forgetting their prejudices and sections, fought to practically the last ditch. The United Federation of Labor will now, from present indications, cease to exist as such, but will merge itself into the Social Democratic Party, which is engineered by Walter Thomas Mills, and composed of labor officials (many discredited), single taxers radicals and what not.

There will be the inevitable political reaction, but as the elections come off next November we won’t have long to wait.

The S.D.P. full of the economics of Henry George, and once in a while, Karl Marx, are going to tax the employers to death, when they get in.

One of them, already in the House of Jaw, has evidently got the revolution well in hand, as he asked for a monument for his Liberal predecessor, new boots for policemen, and better treatment for those strike-breakers and scabs, the small farmers.

When the boss cuts your wages or victimizes you. join the S.D.P. and chastise him with a ballot paper. We are going to have a repetition of the New South Wales Labor (hard labor) Government, and I fully expect our beautiful S.D.P. to jail working men for striking like the Labor Party did at Lithgow in New South Wales, some time ago.

The future organization in these islands is going to be the Industrial Workers of the World. During the recent strike the capitalist press made as much hullaballoo about 100 I.W.W. men as it did about the 30,000 U.F.L. and S.D.P.

The I.W.W. is a growing factor in Australia, and already the Attorney General of New South Wales, (also president Sydney Watersiders), W. Hughes, and the Sydney “Morning Herald,” are denouncing the I.W.W.

In New Zealand scattered propagandists are sowing the seed of the One Big Union in the mining camps, the bush settlements, the wharves and the ships.

The I.W.W. paper the “Industrial Unionist,” perished during the strike, owing to lack of funds; but during her twelve months existence, obtained a 5,500 circulation, and carried the message of revolt far and wide. As soon as we clear up the debt, and get $50 in hand again, we will start her, if possible as a weekly.

The Direct Action outfits are beginning to grow, and as it moves along, gathering impetus, it will shift the paid reactionary barnacle from the pie counter, and drop him into the old men’s home, the S.D.P., where with $1500 a year at his disposal he can make amendments to the Arbitration Act, inaugurate State brickfields and pulverize the conservative squattocracy with the kindly assistance of his Liberal and Progressive soul mates.

The workers in New Zealand have had enough of reform and palliatives; they are acquiring backbone, beginning to fight. They are on the eve of great possibilities. Long live the General Strike and the I.W.W.

Auckland, N. Z., 1-28-14.

TOM BARKER.

The Voice of the People continued The Lumberjack. The Lumberjack began in January 1913 as the weekly voice of the Brotherhood of Timber Workers strike in Merryville, Louisiana. Published by the Southern District of the National Industrial Union of Forest and Lumber Workers, affiliated with the Industrial Workers of the World, the weekly paper was edited by Covington Hall of the Socialist Party in New Orleans. In July, 1913 the name was changed to Voice of the People and the printing home briefly moved to Portland, Oregon. It ran until late 1914.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/lumberjack/140402-voiceofthepeople-v3n14w65.pdf