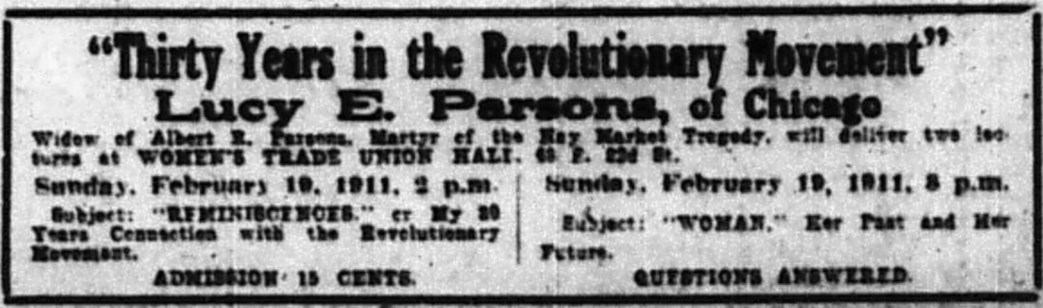

Report on Lucy Parsons’ two talks given at New York’s Women’s Trade Union Hall–‘Reminiscences: Thirty Years in the Revolutionary Movement’ and ‘Women, Here Past and Her Future.’

‘Two Lectures by Mrs. Lucy Parsons’ from the New York Call. Vol. 4 No. 51. February 20, 1911.

Widow of Martyred Worker Speaks on Revolution and Woman’s Status.

Lucy E. Parsons, of Chicago, widow of Albert R. Parsons, martyr of the Haymarket tragedy, delivered two lectures at the hall of the Women’s Trade Union League in East 22d street yesterday afternoon and evening. In the afternoon Mrs. Parsons spoke reminiscently on “Thirty Years in the Revolutionary Movement.”

In her talk Mrs. Parsons traced the history of the American Socialist movement and pointed out the real facts in the case that culminated in the murder of her husband by the state of Illinois.

She declared that the S.L.P., a remnant of which still exists, did not come to the aid of the condemned men. Its press, she said, refused to take up their case, saying the men menaced were after all, only anarchists.

In the evening she lectured on the woman question. Her talk covered the past, present and future status of woman. Only through a social revolution, said she, could woman hope for complete emancipation.

As illustrating the quite recent subjection of women, she quoted from the famous English jurist, Blackstone, who said: “The husband by law has power of dominion over his wife, and may keep her by force within the bounds of duty, and may beat her, but not in a violent or cruel manner.” Again, in 1862, the English lord chief Justice, Coleridge, said: “The husband has the right to confine his wife within his own dwelling, and restrain her from liberty through a certain period.”

In the past household drudgery had been the only occupation open to women; but since the introduction of steam in industrial processes she has taken an increasing share in the world’s work. When woman began, some seventy years ago, to come into industrial and professional life, she had been told that true virgin delicacy was incompatible with learning. But in spite of bitter opposition she had invaded every field of life, and was proving herself competent in them all.

The only thing that made her on a different social level from men today was her lack of a vote, and she was now demanding the vote in order to assert her absolute equality.

Marriage, said Mrs. Parsons, has passed through many stages–polyandry, polygamy, monogamy. We live in the last named stage, and she could only say that if God could not make a better hand of things he ought to go into business for a bit. In a sane state of society women would be as economically free as men, and that freedom would enable them to choose the husband they loved, not the husband whom they thought could “keep” them, as was the case today. Women would demand freedom to live the lives of human beings first, and only secondly as women.

Some form of marriage would, she believed, always exist, but a form much more rational than the present. Women would refuse in future to act as mere “child incubators.” The size of the family would probably be smaller than today, but that was a matter for each woman herself to decide, and concerned nobody else. Quality, not quantity, would be the standard and the object.

Family life, she urged, was perhaps the most beautiful and sane of all human relations. She saw the time coming when man and woman would enter freely into that state as lovers and companions. As the years passed they would tend their children as babies, and as they grew up and ran about the house, taking joy from the childish prattle. They would watch them through youth, and youthful voices ringing through the house would make them glad and bring them ever closer to each other. In the end their children would marry and the house would become still and silent. In that day, as old people, they would look into each other’s eyes and be lovers yet, and when it came to one to die the other would say: “This is the love of my youth and of my old age.”

The New York Call was the first English-language Socialist daily paper in New York City and the second in the US after the Chicago Daily Socialist. The paper was the center of the Socialist Party and under the influence of Morris Hillquit, Charles Ervin, Julius Gerber, and William Butscher. The paper was opposed to World War One, and, unsurprising given the era’s fluidity, ambivalent on the Russian Revolution even after the expulsion of the SP’s Left Wing. The paper is an invaluable resource for information on the city’s workers movement and history and one of the most important papers in the history of US socialism. The paper ran from 1908 until 1923.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-new-york-call/1911/110220-newyorkcall-v04n051.pdf