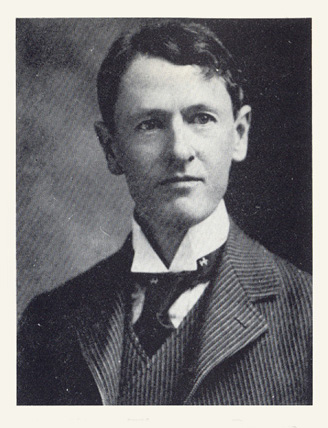

Brown on what is still likely to be the most revolutionary school Salt Lake City ever saw, and from 1911. The ‘Modern School’ inspired by the martyred Spanish educator Francisco Ferrer, executed on October 13, 1909, became an institution for anarchist and left-leaning radical communities in the 1910s. One of the earliest such schools was in Salt Lake City started by Yale-educated former Congregationalist and later Unitarian minister who had become an early and active member of the Socialist Party. An advocate of the I.W.W., on the left of the Party and movement, except for the period of World War One, Brown would become a supporter of the Communist Party in the 1920s. Brown would organize a number of Modern Schools including the famous one in Stelton, New Jersey.

‘Report of the Modern School’ by William Thurston Brown from Industrial Worker. Vol. 3 No. 34. November 16, 1911.

I am glad to acknowledge my debt to the heroic, devoted Ferrer, and when I undertook to give a name to the movement which I desired to inaugurate in Salt Lake City a year ago, I could think of none which seemed to me so fitting as the one with which Ferrer will always be associated–the Modern School. But it is only fair to say that this attempt in Salt Lake City would have been made if Ferrer had not existed, and possibly the same name would have been used, since it describes better than any other the real aim and the actual origin of the movement.

The organization of the Modern School in Salt Lake City was a natural outcome of my own intellectual and spiritual experience. In June, 1910, I definitely and finally abandoned the church because I was convinced that it could not be depended upon ever to perform the function which I had so long felt to be its peculiar mission and opportunity. I felt that no church could be trusted as a moral or spiritual teacher, because no church can be free.

It often happens that a minister abandons the pulpit, and takes up some other occupation. Sometimes it is business; sometimes farming; often some so-called reformative or philanthropic work, such as public charity, penal reform, social settlements, and so on. Carroll D. Wright gave up the Unitarian ministry to become Commissioner of Labor at Washington. Samuel J. Barrows left the pulpit to identify himself with our prison system. A large number of ministers have turned from the church to the Socialist movement. In all such cases, it is simply the attempt of human life to find a more adequate expression, often a more adequate religious expression. Something like that befell me. I could no longer express myself or my religious aspirations in the church.

With a net income above rent of hall and advertising of about $25.00 a month, derived in part from the adult membership fee of one dollar a month, in part from collections at Sunday evening lectures, it is obvious that we could not hold daily sessions of the school. The most we could attempt was a weekly session held on Sunday afternoons. The children’s department was a substitute for the usual Sunday school. But instead of the studies or lessons and exercises of a Sunday school as understood by the church, we gave the children in our school just the simple facts of life as science gives them to us; how the world came to be; the natural history of the earth; the origin and unfolding of life on the earth–all kinds of life, including the human; and incidentally and progressively the origin and evolution of society and social forms, our purpose being to give the children or permit them to discover for themselves the scientific conception of the world and of life—the only one that can breed a really religious spirit. Human beings, young or old, must get the scientific, evolutionary point of view, if they are really to live.

The particular books upon which this work with the children was based were “The Story of Creation” and “The Story of Primitive Man” by Edward Clodd; “Mutual Aid as a Factor on Evolution” by Kropotkin; “Our Universal Kinship” by J. Howard Moore; “The Evolution of Man,” by William Boelsche; “The Making of the World,” by Meyer; “The Germs of Mind in Plants,” by French; “Mother Nature and Her Children,” by Gould, and others.

It will be understood that our method was not that of loading the children’s minds with definitions or precepts or anything of the kind. They simply were learning facts often by immediate observation and experiment Fortunately, the facts were largely new to the teachers they were learners with the children–an ideal condition, provided the teachers are single-minded in the desire to learn the facts. Inevitably, the learner will draw inferences from the facts and so get a philosophy of life bit by bit.

It goes without saying that no attempt was made to teach anything about a God. I doubt if anything corresponding to the old notion of God will remain in what Ellen Key calls the “religion of life,” the religion of evolutionists. The real spiritual interests of the modern world–the world that has something of the spirit of science–will not be in metaphysics, but in processes, in what is actually going on, and in what society and the individual can do to cooperate with these processes.

Of course this is not all that a Modern School can do for children. But I believe it is the groundwork of what such schools must do. The Modern School must not make the mistake of supposing that its purpose is to build up a little heaven in the middle of hell, to establish a little Utopia in the midst of this ruthless capitalism. To attempt that is to emulate the futile and fruitless ethics of orthodox Christianity, of Capitalism itself, for that matter. In my judgment, the object of the Modern School is to create intelligent revolutionists, to plant the seeds of rebellion in the hinds of youth. That is the measure of any human beings efficiency.

Following the simple plan which I have described and which we had time merely to begin, the children not only learn the simple facts and truths of astronomy, biology, comparative anatomy, physiology, and so on, but the use of this method must also show them the deeper meaning of history of society, of sex, of all that concerns them. It must be obvious, too, that such a method creates its own atmosphere and carries with it the whole rationale of modern education. As a matter of experience, there was never any loss of interest on the part of our children. We were obliged to extend the time of their session from an hour to an hour and a half and often two hours. One of the principal teachers in this department, Virginia Snow Stephen, daughter of a former president of the Mormon church, and instructor in art in the University of Utah, said it was the most inspiring work she ever did, and she proposes, as soon as possible, to give all her time and strength to the Modern School movement.

A total of 60 children were registered during the year, and the average attendance was excellent. The question of discipline never arose, so far as I know. The school was a demonstration that perfect freedom, the absence of all written rules, and the sense of solidarity give children all the motive needed for conduct. Classes were quite informal. Two or three groups of children, ranging in age from four to seventeen or eighteen, classified according to age and mental aptitude, were gathered in a social way around long tables, with teachers. Each one was provided with pencil and paper. Whatever was being studied read or talked about was also sketched by the children or written about, or both. Flowers, plants, pictures, fossils, and so on, were at hand, often brought by the children themselves.

Besides the study work, some time was always given to singing.

One of the most valuable discoveries we made in our year’s experience, too, was the fact that what is needed for the children–what proved of never-failing interest to the children–is equally the first need of adults. The Modern School must make it a primary object to give the adults this evolutionary point of view as the ground work of all their further thinking. Adults cannot think effectively or fruitfully of economics or social problems of any kind, until they gain the evolutionary standpoint.

The work of the Modern School for adults, consisted of a class in economics every Sunday afternoon, the Sunday evening lecture, which included many phases of social science and the revolutionary movements of the world, and the class in Modern Drama. The class in economics was not very successful. The responsibility of this was mine. I had not sufficient physical vitality to do justice to all I had to do, and this was the neglected work. Besides, it was not a good time of day to get any considerable number of men together for such a study. But the class devoted to the study and interpretation of the Modern Drama and kindred literature was always intensely interesting. Within it a range were included plays by Ibsen, Shaw, Sudermann, Hauptmann, D’Annunzio and Strinberg; and writings of Thoreau, Oscar Wilde, Anatole France, Edward Carpenter, Maeterlinck, Bebel, Ellen Key, Havelock Ellis and others.

The Sunday evening lectures, which drew a growing audience of deeply interested people, were devoted to many phases of the revolutionary movement in science, in economics, the labor movement, the ethics of sex relation, and so on. The audience contained socialists, anarchists, freethinkers, and various shades of opinion. And yet, I think it became for many of them a sort of religious meeting. We sang revolutionary songs at the opening and closing–nearly always “The Red Flag” and “The Marsellaise.” Time was always given for questions and brief discussion at the close of the lecture. And it was uniformly the purpose of the lectures to stimulate the spirit of hope, courage, earnestness, and determination in his listeners.

I do not think that the Modern School in Salt Lake City could be called a failure in any sense. To be sure, we did not succeed in financing it, that is in raising money to support the principal and his family. But it has already been demonstrated in Portland, Oregon, that considerable money can be raised for such a purpose, and a guarantee of $150 a month has been promised me, in order to make it possible for me to give my whole time to that work.

In general, the Modern School, in my judgment, should be frankly a school of the revolution, should be in cordial alliance with the proletarian revolutionary movement of today, though not identified with any particular school of thought. It cannot teach the plain facts of science and history without rendering fundamental service to every libertarian movement. And I believe it may everywhere be a leaven of liberalizing power, both for the community in general and for the public schools–especially in cities somewhat smaller than New York or Chicago.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iw/v3n34-w138-nov-16-1911-IW.pdf