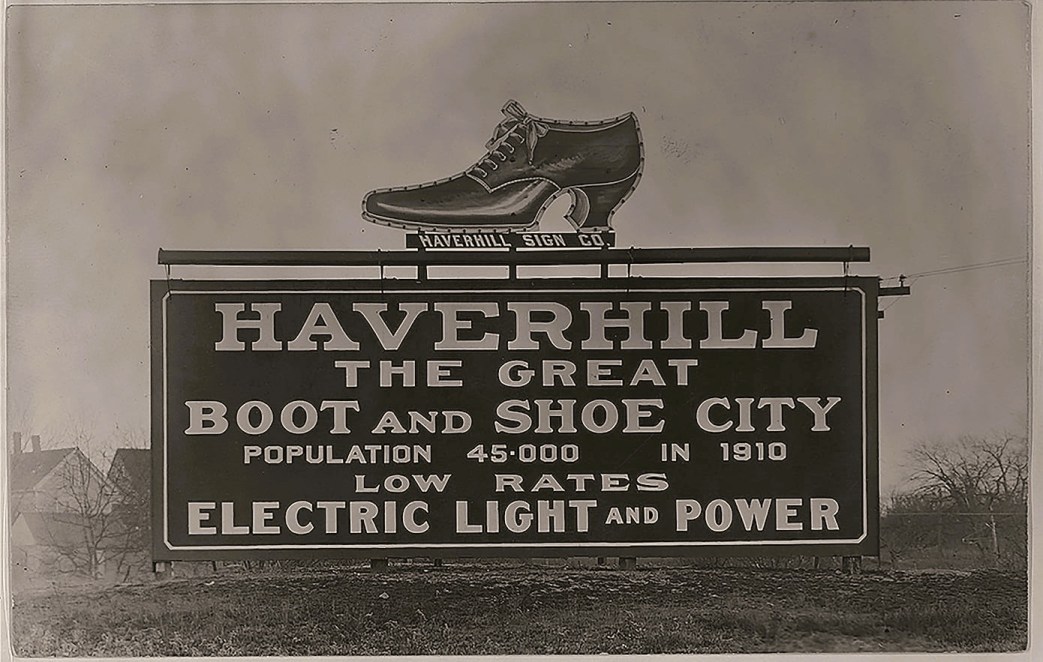

How militants from the Protective Shoe Workers Union in the Massachusetts shoe-making center led 5000 workers from different unions and the unorganized in a largely successful strike.

‘How the Left Wing of the Shoe Workers Won a Strike at Haverhill’ by William J. Ryan from Labor Unity. Vol. 2 No. 3. April, 1928.

IN BOSTON, on March 4, was held one of the most important conferences for the shoe workers in recent years. Following on the successful left wing strike in Haverhill where, in spite of the final treachery, a clearcut victory was won, sixty delegates representing the Boot and Shoe Workers, the Protective Shoe Workers Union, and the unorganized, met and canvassed the whole field, decided on a militant campaign for united front against the bosses and for organization of the unorganized. A National Committee has been elected. It will meet monthly and will publish a bulletin. The Workers Clubs which have been springing up among the organized and unorganized especially in Lynn will be supported. Plans are being made to organize left wing sentiment against the officials who have practically made a company union out of the Boot and Shoe; the left wing in the Protective, which opposes the reactionary national leadership, will be supported and the whole struggle coordinated by the national committee. The national committee is issuing a detailed program of struggle which will be printed in Labor Unity.

“WAGE reductions must cease!”

“No compromise!”

“1927 prices or nothing!”

Five thousand striking shoe workers packed in the largest halls in the city of Haverhill clamored and shouted these answers to a compromise proposition of the shoe manufacturers and their allies, the bankers, politicians and business men of the city. Ten days before, January 18, 1928, they had poured out of the Haverhill shoe factories in protest against a wage reduction. They had taken this action at the call of a secret rank and file committee known as the Emergency Committee, in complete defiance of an arbitration agreement; and only a few nights previous they had paraded the streets of the city as a demonstration of their strength, solidarity and determination.

For ten days the public press had cajoled and threatened and denounced, business interests had used their influence, shoe manufacturers had threatened to leave the city; and every ounce of influence that could be used in a small city where there is only one industry was brought to bear on the striking shoe workers.

Now, with their general officials advising acceptance of the compromise proposition and after the most bitter and intensive propaganda campaign directed against them, they staged the most wildly enthusiastic meetings of all, and unanimously gave their answer:

“1927 prices or nothing.”

“Wage reductions must cease.”

“No compromise!”

Up to January 1924 the Shoe Workers Protective Union had justly been acclaimed as one of the most militant and progressive labor unions in the country and certainly the most advanced organization in the shoe industry. In the matter of hours and wages it set the pace for the shoe workers of the country and in shop conditions it stood alone. Indeed it was its insistence on shop control and its work in developing the shop committee system that particularly marked the Protective as a progressive and militant group.

In addition to its work in its own particular sphere it actively interested itself in the general problems of the labor movement. It was one of the earliest in advocating the amalgamation movement and consistently supported this program. The Protective would not agree to bind itself to a policy of arbitration, and one of the articles in the proposed constitution stated that “the policy of this organization may be a policy of arbitration and conciliation.” The article originally read “shall,” but was changed to “may” when it became evident that something must be done to placate the Protective. It was a distinction without a difference. The Protective understood that conditions might force them to adopt an arbitration agreement, but they refused to accept arbitration as a policy of their organization.

There were other points of difference also, but whatever the emphasis placed on these various points the arbitration article was the real point on which the movement differed.

The Protective supported the workers everywhere to the limit of its ability. Thousands of dollars were donated to Rochester and Brockton shoe workers. Truck loads of food and thousands of dollars in money were given to the Lawrence textile workers and a loan was thrown into that city at the critical time of the 1922 strike. The organization published a paper that found plenty of room for revolutionary propaganda, organized a Chamber of Labor in the city, and gave its support to organizing workers outside of its own trade. In short, the Shoe Workers Protective Union by deed and propaganda showed clearly that it recognized the class struggle and with all the drawbacks, incidental to a New England psychology, it performed its work well.

Naturally the organization was hated by the manufacturers and business elements of the city. One section of the local press kept up a steady attack week in and week out concentrating its attention on the “Reds” and appealing to the conservative element in the organization to throw off the yoke of the “tyrants.”

In December 1922 the union administered a particularly humiliating defeat to the shoe manufacturers. Smarting under this and taking advantage of the beginning of the industrial depression in the shoe industry they manouvered what was equivalent to a five month lockout in the latter part of 1923. The factories remained open, there was no direct war, but there was no work, and thousands of workers were walking the streets. They had jobs, thanks to the union shop control—but no work.

The propaganda campaign was intensified; the Protective was conducting a strike in five factories involving about two thousand workers; and the manufacturers were solidly organized. In addition to this in the rest of the country the shoe industry had collapsed. The organization in Rochester, N.Y. had been destroyed, and Lynn, Mass. had granted extension in hours and reductions in wages. Haverhill was isolated.

Left Wing Plans To Carry On

The Protective barely avoided a most disastrous defeat. The organization signed a “Peace Pact”— the manufacturers gave it that name—surrendering some of the things they had won but still holding itself well in advance of the rest of the country in the desperate hope that they would receive support.

They were doomed to disappointment. Beginning with January 1924 the Haverhill shoe workers lost steadily.

The deflation period could not be successfully met by an isolated center, and in the shoe industry particularly the depression was severe. Add to this the fact that the “Reds” had met with defeat inside the organization and the union was controlled by extreme conservative and reactionary groups.

The class conscious groups concentrated on the two chief problems, namely, to preserve the organization and to carry on quiet but persistent propaganda in preparation for the future.

Under the terms of the “Peace Pact” a general wage hearing was held every year, and the impartial chairman was called upon to decide the entire wage scale for the city.

The arbitration board consists of a union representative, a manufacturers’ representative and an impartial chairman. The impartial chairman is under salary, paid by each of the parties, and he decides questions on which the workers and employers cannot agree. The agreement says his decision is final and binding. The present arbitrator is a former business agent of the Protective. He was not supported by the union.

The union employed the Labor Bureau, Inc. of New York to present its case for an increase in wages, as it has for the past few years. The Bureau did a complete and splendid piece of work. The manufacturers prepared their own brief—a blunt statement that they wanted a cut.

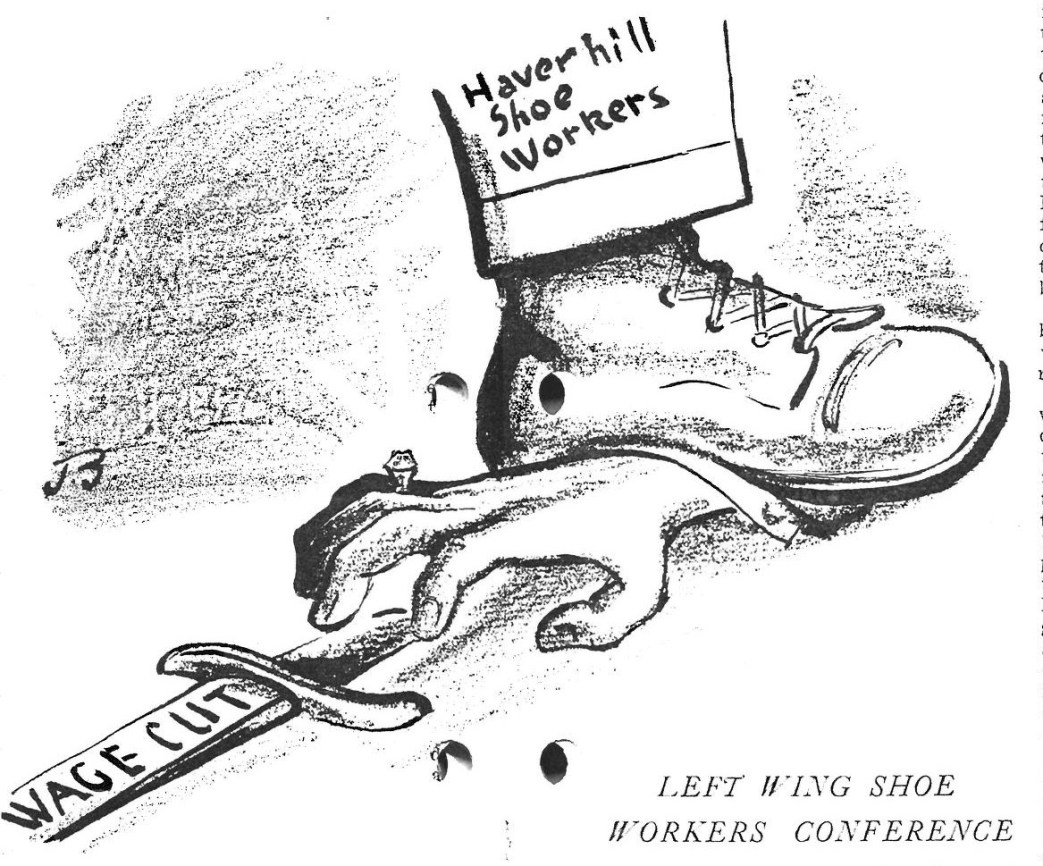

The Impartial chairman—the union calls him “Impossible Chairman”—handed down a decision giving general wage reductions on piece prices and establishing a sliding scale on week wages.

The militant element in the organization sprang to immediate action. General economic conditions seemed to indicate that the hour was ripe for a successful battle. Local conditions indicated the same course. The Manufacturers Association was weak, and shoe business was promising. But the determining reason was organization policy. The time had come when organized labor in the shoe industry was confronted with the alternative of “dying on its feet” or fighting. If it fought a good fight and lost—it didn’t lose. However severe the apparent defeat at least the militant and progressive elements would retain their respect for the organization and they would form a nucleus for future reorganization. If the union accepted the decision all hope and courage would be quenched and the organization would melt into nothingness. Add to this the theory that was in the minds of a few that organized labor must openly resist the general offensive of the bosses that has been carried on for the past few years. Some effort must be made, however small, to awaken the fighting spirit of the workers. And finally if the Protective was to grow, if the shoe workers were to be organized, then the Protective must be able to show that it is ready and willing to fight.

Rank And File Take Charge

The local unions most affected by the cut formed Emergency Committees giving to these committees full power. The committees were of the rank and file and by “full power” the workers meant just what the term implies. Officials, boards, and all machinery of the locals were subordinate and under the control of the Emergency Committee.

The Emergency Committee, representing the locals which had been cut, outlined for themselves four immediate tasks.

1. To get all the shoe workers in the city into the movement.

2. To keep the General Officials from interfering.

3. To organize public opinion if possible. This is important in a small city, and especially so in a city depending upon one industry.

4. To delay the strike if possible until such time as a walk-out would most seriously affect the manufacturers.

In the meantime a special sub-committee was assigned to the one task of working out plans to enable the shoe workers to carry on the battle for months if it should be necessary.

The Emergency Committee succeeded in accomplishing its four immediate tasks.

The first, of lining up all the shoe workers, proved comparatively easy. Direct appeals to the local unions that had not been cut brought immediate response, and the day workers, even though they had not been directly affected, realized the danger of the proposed sliding scale and rallied to the general program. The plot to divide the workers was defeated. A small group among the turn-workmen or turn lasters held that local for awhile even to the extent of publicly denouncing us but our committee succeeded in reaching the mass of that local and the reactionaries were publicly repudiated.

The second task, that of preventing the general office from interfering proved more difficult. It was accomplished, however, and in plain justice to the general president it must be noted that he did nothing to break the spirit of revolt. Only when the compromise proposition was opened did he definitely urge the workers to surrender.

Anxious To Struggle

The third task, that of organizing public opinion was at least partially accomplished, despite the hostility and bitterness of the press: The very determination and earnestness of the workers, the fact that they had consistently accepted wage reductions without complaint, the unwarranted amount of the reduction, and their willingness to submit their grievances to public judgment, all had effect. The Citizens Committee, the Arbitration Board, the shoe manufacturers were besieged with petitions from the workers to reopen the case. Finally the banks in the city began to feel the effect of the workers’ spirit. The workers had withdrawn thousands and thousands of dollars from the banks in order to protect their savings from possible legal action in the event of a strike.

The fourth task, that of delaying the actual walkout was at one and the same time the easiest and most difficult. It was the easiest because the work necessary to accomplish the first three required time and so helped the general plan. It was the most difficult because of the impetuosity of some of the groups which reflected itself even in the Emergency Committee. It was vital, however that the blow be struck at a time when its effects would be most seriously and quickly felt by the bosses, and by dint of hard work and considerable diplomacy the desired result was attained.

A few days before the strike was called general mass meetings were held in various halls. These meetings adjourned simultaneously and thousands of workers thronged the streets marching from one hall to another where they heard various speakers.

Wednesday, January 18, was set as the deadline by the Emergency Committee, and that night, learning of the refusal of the manufacturers to confer with them, the Shoe Workers Protective Union in crowded mass meetings called a strike in every shoe shop in the city of Haverhill. At these meetings they definitely decided on the policy “No Compromise”—”1927 Prices or Nothing.”

Thursday, the 19th, not a wheel turned in any Haverhill shoe factory.

From that date until January 30, the date of the surrender of the Haverhill Shoe Manufacturers Association, things moved with bewildering rapidity. To the casual observer the union headquarters presented a scene of chaos, workers thronging the building day and night attending their strike meetings, and with local officials aimlessly wandering about, neglected, forgotten, and ignorant of what was really happening. The strange term “Emergency Committee” was on every tongue, but where the Emergency Committee was, who it was, and what it was doing nobody knew with any certainty.

But there was a very definite thread of order running through the apparent chaos. The meetings were organized without the officials, or with the aid of the few officials who had courage enough to help. Factories were signed up, and the general feeling of hope and courage and determination was kept alive.

Then came the break The manufacturers and the Citizens Committee met with the general president, the attorney, and the president of the district council. They would pay 92% of the 1927 prices “on account,” the entire wage case would be reopened and heard by a new arbiter.

The general president and the attorney went before mass meetings and advocated the acceptance of the proposition. It was with difficulty that the workers were persuaded to even listen to the plans. Out of five thousand workers two voted to accept it. The shoe workers of Haverhill returned their answer to the bosses—

“No compromise!”

“1927 prices or nothing.”

“Wage reductions must cease.”

On Monday, January 30, the Haverhill Shoe Manufacturers Association capitulated and granted in full all the demands of the Haverhill workers.

This strike is something more than a mere local disturbance, and its effects will not be confined to Haverhill or even to the shoe industry. It marks the awakening of the workers fighting spirit after several years of general passivity. The general offensive of the bosses against labor which has been pressed so ruthlessly during late years may not be definitely halted or even retarded by this one demonstration in a comparatively unimportant industry, but the very fact that a large number of workers in the face of a “sacred” agreement, public opinion, and internal opposition, definitely and militantly asserted themselves is to say the least a hopeful and encouraging sign.

The effects are already being felt in the shoe industry. The Protective is pressing an organizing campaign which if properly handled, should meet with considerable success.

There has been a general awakening, a return of that keenness, alertness and interest that has been so markedly absent in recent years. This newly roused spirit must be fostered and directed. This is the work of the progressives in the shoe industry, and upon their ability to meet this task successfully rests the immediate future of organization among shoe workers.

Labor Unity was the monthly journal of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), which sought to radically transform existing unions, and from 1929, the Trade Union Unity League which sought to challenge them with new “red unions.” The Leagues were industrial union organizations of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) and the American affiliate to the Red International of Labor Unions. The TUUL was wound up with the Third Period and the beginning of the Popular Front era in 1935.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labor-unity/v2n03-w22-apr-1928-TUUL-labor-unity.pdf