In an editorial dismayed at the increasing influence of socially middle class and politically opportunist leaders in the Socialist Party, Kerr says the Party preparing for revolution is the best way for it to wring out reforms.

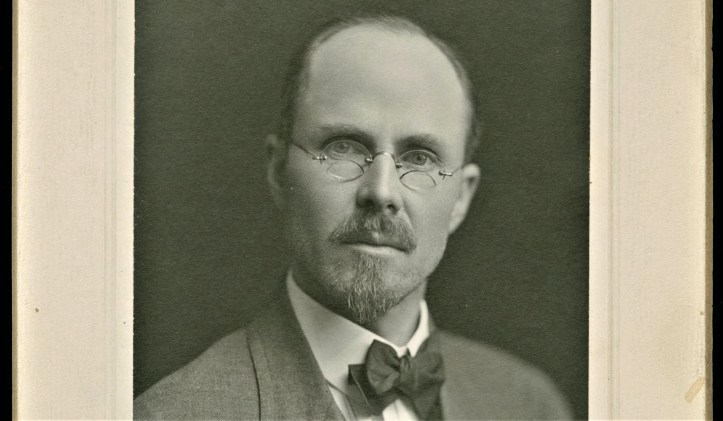

‘Socialism Becoming Respectable’ by Charles H. Kerr from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 9 No. 12. June, 1909.

Comrade Kohler’s communication in this month’s “News and Views” department shows how the signs of this process strike a proletarian. But some of our socialist readers may think that he is misinformed or has misinterpreted the recent acts of some of our party members. We therefore give a somewhat lengthy quotation from one of the most respectable periodicals in the United States, the Congregationalist and Christian World of Boston. In its issue of May 15, Prof. John B. Clark of Columbia University, a man who stands in the very front rank of Capitalist economists, writes:

“Not at once by a single stroke is it proposed to confiscate private property. The effort will be made to reach the goal by a series of approaches, although the goal is kept constantly in view and the intermediate steps are to be taken in order that they may bring us nearer to it. What should we do about the movement while it is pursuing this conservative line of action? If we could stop it all by a touch of a button, ought we to do it? For one, I think not. On the general ground that it represents the aspirations of a vast number of working men, it has the right to exist; but what is specifically in point is that its immediate purposes are good. It has changed the uncompromising policy of opposing all half -way measures; it welcomes reforms and tries to enroll in its membership as many as possible of the reformers. It tries to secure a genuine democracy by means of the initiative and the referendum—something that would accomplish very much of that purification of politics of which the Socialist and others as well have so much to say.

“Factory laws, the abolition of child labor, the protection of working women and the proper inspection of factories are measures that we all have at heart; and most of us desire the gradual shortening of the working day and general lightening of the burden of labor. When it comes to a public ownership of mines, forests, oil wells and the like, there are few of us who are not open to conviction and many of us are ready to assent to that policy by which the government holds on very carefully to such properties of this kind as it possesses and even acquires others. Inheritance taxes and income taxes, which the Socialists desire, have been widely adopted. In short, the Socialist and the reformer may walk side by side for a very considerable distance without troubling themselves about the unlike goals which they hope in the end to reach.

“Will it be safe to join the party and work with it, as it were, ad interim? The platform is always there telling very distinctly whither the movement is tending, and it is no modest platform which even the immediate demands now constitute, if we take account of all of them; for it includes the national ownership of railroads and of all consolidated industries which have reached a national scale and have practically killed competition. It demands the public ownership of land itself, a measure so sweeping that our kindly farmer would feel restive in the ranks if he really thought there was any probability of its adoption. What the reformers will have to do is to take the socialistic name, to walk behind a somewhat red banner and be ready to break ranks and leave the army when it reaches the dividing of the ways.”

Will it be safe for the capitalistic reformers to join the Socialist Party for the sake of bringing about reforms which tend to delay the collapse of capitalism? Professor Clark thinks it will, and he is a man of no mean ability. But if he is right, will it be safe for the Socialist Party to shape its policy with a view to catching the votes and even the membership applications of these reformers, who will be, in Professor Clark’s words, “ready to break ranks and leave the army when it reaches the dividing of the ways”? That is the issue that must be met within the Socialist Party in the near future. There will be no lack of arguments on the reform side. There are hundreds of efficient party workers who have put in many hours of unpaid labor, and who feel that the fat salary of a public official would be a suitable reward. And the salary is a possibility if we can only attract enough reformers to come in and help with their votes. There are party editors working for uncertain salaries whose pay would no doubt be sure and liberal if the reformers’ money could be poured into socialist channels. And behind these few, who perhaps after all are influenced rather unconsciously than consciously by their material interests, there are many thousand converts who have come to us through sentimental sympathy rather than class consciousness, who will accept Professor Clark’s overtures with joy, and with not a thought for the collapse of the allied army “when it reaches the dividing of the ways.” Opposed to these will be found an increasing number of wage-workers in the great industries, whose personal experiences have taught them the vital reality of the class struggle, and by their side will be those whose study of socialist literature has convinced them that their own ultimate interests are bound up with those of the wage-workers. We who take this position hold that it is better to let the reformers do their reforming outside the Socialist Party rather than inside. We hold that the function of our party is to prepare for the revolution, by educating and organizing, and that the quickest way to get reforms, if any one cares for reforms, is to make the revolutionary movement more and more of a menace to capitalism. Two things are certain.

One is that the opportunists, so highly commended by Professor Clark, now hold most of the official positions in our party and control most of our periodicals. The other is that the great mass of the city wageworkers remain utterly unmoved by the eloquent propaganda of opportunism. The outcome? That will turn on forces stronger than arguments. Captains of industry are making revolutionists faster than professors and editors can make reformers. And when revolutionists shape the policy of the Socialist Party, reformers will find little in it to attract them.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v09n12-jun-1909-ISR-riaz-gog.pdf