The decades-long struggle to unionize New York City’s massive transportation system, all of the employees on its busses, trains, subways, and ferries, is one of U.S. labor’s great stories. Today, with tens of thousands of workers, Transit Workers Union Local 100, organized in the mid-1930s, remains one of the country’s strongest labor organizations. That unionization helped pave the way for 1940’s purchase by the city of the private operators to for the public New York Subway. Below, the Labor Research Association’s Robert Dunn’s valuable account of the mid-1920s failed effort by workers to break the Interborough Rapid Transit’s company union and form the Consolidated Railway Workers of Greater New York.

‘The Brass-Knuckles Santa Claus: Company Unionism on the I.R.T.’ by Robert W. Dunn from New Masses. Vol. 1 No. 5. September, 1926.

NOW we know what an “outlaw union” is. We used to hear the Honorable Sam Gompers throwing it into the I.W.W., the Amalgamated Clothing Workers and other non-A.F. of L. bodies. He told the world that they were outlaws—which was supposed to finish them off. But now we have a new use of the term. The New York Times and other friends of union labor have seized upon it. An “outlaw union,” they declare, is any body of workers that decides to rebel against company unionism and join the American Labor Movement.

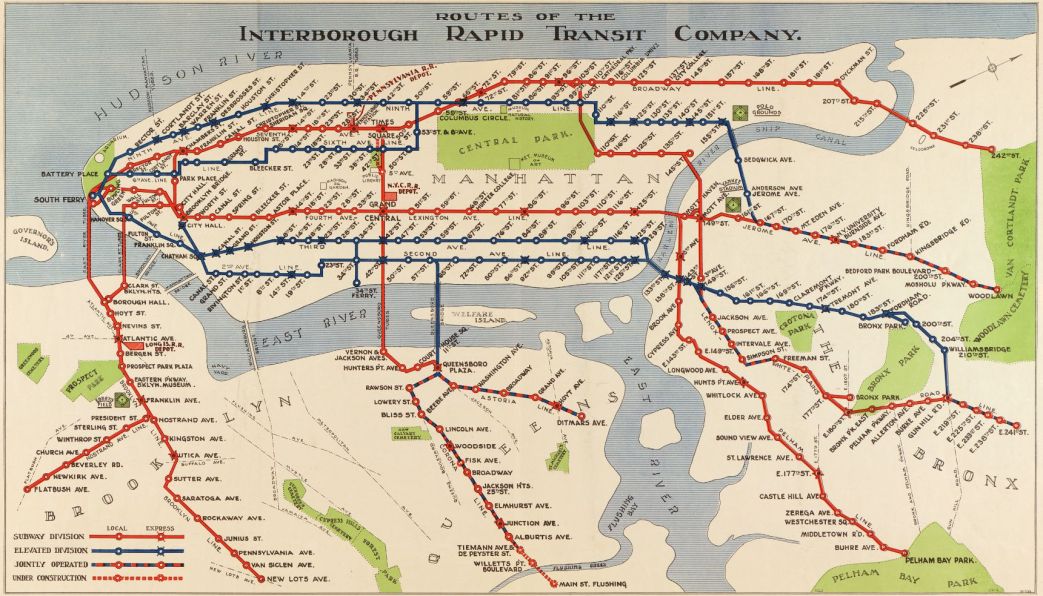

This application of the term grows out of the strike of motormen and others on the Interborough Rapid Transit Company of New Y ork City. These workers attempted to throw off the shackles of the company union, known in this instance as the Brotherhood of I.R.T. Employees, and to establish themselves in the Consolidated Railway Workers of Greater New York looking toward affiliation with the A.F. of L. Mr. Frank Hedley, President and General Manager of the company refused to deal with the new union. He claimed he had a sacred contract with his “Within the Family Brotherhood.” He would deal only with loyalists. Not with outlaws.

It is interesting to note how Frank Hedley and other $70,000-a-year executives of the I.R.T. got this way. It started more than ten years ago, before America entered the war. The late Theodore P. Shonts was then head of the company assisted by Mr. Hedley. Mr. Shonts was a paternalist toward his workers in order, of course, to keep them away from “outside” labor unions. He installed a gilt-edged Welfare Department in 1914 and provided his 1 4,000 workers with athletic associations, a baseball pennant league, voluntary relief, a “Sunshine Committee,” (he really called it that) and I.R.T. bands, all under the direction of a welfare expert at $1 5,000 a year. Shonts appeared at luncheons given by the National Civic Federation to tell the labor leaders and corporation magnates assembled what sweetness and light was exuded by this Welfare Department, reciting to the delighted luncheonists how one five dollar gold piece was bestowed at Christmas time on all employees of his happy family whose average monthly pay envelope returned less than $125. Every one thought Mr. Shonts and his company very generous in the role of Santa Claus.

Then out of a clear sky appeared some agitators, otherwise known as business agents, direct from the headquarters of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America, presided over by William D. Mahon, friend of Gompers and a Civic Federationist himself. These ungrateful agitators proceeded to call a strike of street car workers, first in Yonkers, then in the Bronx and finally on the lines of the I.R.T. in Manhattan. The subway and “L” men joined the strike, in spite of welfare. They struck in protest against a violated agreement and against the threat of “master and servant” contracts which the company was secretly forcing the men to sign. They struck against the wholesale discharge of workers who had the spirit to wear union buttons.

The company refused to deal with such an alien device as a labor union, and Shonts and Hedley spent over two million dollars to break the strike—63 per cent of this amount going for strike breakers. They also continued to carry out a bright idea—the installation of a company union. It is said that they bought this idea from Mr. Ivy Lee, public relations expert for John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and premier shirt stuffer—more recently associated with attempts to break the Passaic strike. Poison Ivy had just put in a company union out in Colorado after the Ludlow massacre. The I.R.T. got him on its payroll at $12,000 a year and he obligingly hatched this little scheme.

The company union was installed. The workers were split up into 33 locals, delegates from which were elected to a General Committee. The President of this committee became the virtual overseer and boss of the workers. But the I.R.T. went even farther than most company union practitioners. By fraud and coercion and promises of higher wages it had, even before the strike, induced its workers to sign individual agreements—yellow dog contracts—which, in effect, “closed” the shop to all but “Brotherhood” members. Any worker refusing to join found himself on the street. There was no “freedom in employment” or “American Plan” open shop such as employers’ associations usually advocate in theory when faced with the labor union. It was a 100 per cent closed shop against trade unionism and in favor of the company—a virtual company peonage system, set up and protected by a barrage of words about “the spirit of mutual confidence, good will and happiness,” about “man to man” and “united we stand” and many other slogans stolen from the trade union handbook.

It worked. It broke the strike, and the company forthwith returned thanks to the Almighty and to its slaves who had remained “loyal” during the Amalgamated onslaught. The President of the Company observed at the time that “the attitudes our men have manifested will be seen and recognized by the whole country as a monument to manhood.” But in 1917 we find the Amalgamated again attempting to line up the workers on the Interborough. Whereupon a resolution written by the legal expert of the company and signed by the officials of the company union was issued. It expressed the servile relationship of the “Brotherhood” representative to the company which controlled his job. In part it read:

“Whereas recently some of the labor agitators of the Amalgamated who unsuccessfully attempted to interrupt service on the I.R.T. lines last fall have returned to the city and publicly announced to the press that they are here to cause trouble…the outside labor agitators who are endeavoring to create a controversy are in no way representative of the employes of the I.R.T. Company…we have not requested and do not desire them.

And the company union puppets called on the good mayor of the city to prevent “attempts by organized violence to interfere” with their pretty little inside union. This referred to the organizers of the Amalgamated who had come to town to organize workers with the approval and blessing of Samuel Gompers himself.

As a result of this joint assault of the I.R.T. management and its trained seal union upon the A. F. of L. organizers the efforts of the latter proved fruitless and Mr. Shonts wrote to Oscar Strauss, then Chairman of the Public Service Commission, that he believed it to be against the public interest to have employees affiliated with a labor union, implying that the “Brotherhood” was anything but a labor union. He further asserted that “sympathetic strikes,” such as might occur if the workers belonged to a real union, could be averted under “our plan” and under “our own Brotherhood Rules which have been approved by our Directors,” meaning the Board of Directors of the I.R.T.

So the Brotherhood flourished and waxed fat. It sent its quota of boys overseas to hang the Kaiser; it attended the Rev. Billy Sunday’s burlesque in a body accompanied by the Interborough Band and the Welfare Shepherd; it purchased Liberty Bonds by the barrel and voted for wage decreases to keep the company out of its ever conveniently threatening receivership. And by 1919 we find it calling itself a labor union. In fact the President of the “Brotherhood” then wrote of it as “a progressive formation amongst employees of the Interborough, whereby they, with the approval of the Management, formed themselves into a labor organization.” While a company official writing in the Interborough Bulletin, the Family Magazine of this great Family Railroad, called it “the strongest labor organization in New York City to-day, and the members are quite capable of conducting their own affairs without the aid of outsiders and paid professional agitators.” Mind you, these agitators were none other than Messrs. Mahon, O’Brien, Fitzgerald, Shea, Reardon, Vahey and other good Irish brethren, the very pillars of the A.F. of L. It nearly breaks one’s heart to hear such eminent labor patriots called agitators and “alien highbinders” by these company union helots. They even went so far as to charge the Amalgamated with “preaching the Tyranny of Capitalism and the Oppression of Labor” and referred to these excessively “regular” labor men as “these strangers masquerading in the guise of brothers.”

There was nothing too servile for the private “Sisterhood” members to do. They wrote letters to the President of the company addressing him as “Honorable Sir” and assuring him what a big, solid, efficient no-strike organization they had to do his bidding. They called the A.F. of L. union “an outside organization” and said of it: “It can only undermine our discipline, can incite disloyalty among us, and the public will suffer.” Note their tears for the public. They are always promising the public no interruption of service. Which means it is a strike-proof union, a union in the Interborough’s vest pocket. And so it remained until 1 926.

On the tenth anniversary of the “Brotherhood” an eruption took place in what the unctuous editors of the New York Times call “self-government in subway transportation…where the workers have shared in managing industry.” Oh, how they have shared! For example they shared in July, 1921, when in order “to show their cooperation with the present management of the company in its efforts to preserve the solvency of the company” they accepted a 10 per cent slash in wages. And they always shared in the company’s agitation for a fare increase. Indeed, their only “strike” which lasted but a few hours in 1919 was said to have been the result of collusion between “Brotherhood” and boss on behalf of an increased fare. This abortive strike was called from the offices of the company, over company wires by the present President of the “Brotherhood,” Patrick J. Connolly, who, incidentally, was originally a strikebreaker imported from Chicago.

Into the midst of one of these scenes of sharing and tender affection broke the strikers of 1926, specifically the 700 members of Local No. 7 of the “Brotherhood” comprising the motormen and switchmen of the subways. These workers, among the highest skilled in the service, refused longer to endure the annual farce of wage agreements with the company under which wages stood “as is” for another year. After a thirty minutes “conference” between the “Brotherhood’s” General Committee and the company the latter was in the habit of announcing that wages would remain as they were for another twelve months. It had happened so in 1925. The motormen were determined it would not be repeated in 1926. Yet it was, and the motormen were one of thirty-three locals bound by the General Committee’s agreement. They could stand it no longer. They instructed their delegates to secede from the company union, form a new union and put in demands for wages and conditions.

What happened is familiar to readers of this story. Mr. Hedley, 72 hours before the strike began, was hiring strike breakers and guerillas in half a dozen cities while to the press he breathed hypocritical phrases about the sacredness of his obligations to his slaves. He announced that all strikers would be immediately fired. He pointed to the yellow dog contract. He placed his hand over his heart and talked about the sanctity of agreements and about “keeping faith with the Brotherhood” and how they would all strike if he recognized the new motormen’s organization!

But Ed Lavin, Harry Bark, Joe Phelan and their associates were sick of this “reptile company union stuff” as Lavin called it, “this choking thing” misnamed a “Brotherhood.” They made the break and 700 of their fellows followed them to Manhattan Casino and signed up in the Consolidated Railway Workers’ Union of Greater New York. Later they were followed by 150 men from the motive power department lead by Jim Walsh, as well as a scattering of workers from the “L” lines and the signal towers. Such an open defiance of a company union tyranny had never been witnessed since John D. instituted his model scheme in Colorado. Hedley’s big happy family stuff seemed to be leaking. It was an anxious hour for the transit monarchs.

They determined to crush these Spartici and all their followers regardless of cost. Ultimatums, refusals to arbitrate anything with anybody, damage suits, injunction threats, the Industrial Squad, spies, shooflies, beakies, finks, pluguglies, blacklisted, piled on each other’s heels as the I.R.T. drove one smashing blow after another at the workers’ new union. Mr. Hedley moved to take the strikers’ property, impound their unpaid wages, send them “up the river.” The local politicians contributed the Industrial Gangster Bomb Squad for thirty of the most brutal minutes ever witnessed in a civilized country since the Tsar of all the Russias toppled. Even the dirty tabloid sheets gasped in amazement and shouted “This is Not Passaic!” But the organized violence of the state had done its bit and the blackjack had contributed its part to the unseemly farce of company union strike-breaking.

Mr. Hedley and Mr. Quackenbush, always truculent, boastful and autocratic were using precisely the same forces, and even the very phrases, they had used in 1916. “Let me warn you that the course of the company ten years ago will be its course this year.” Again it was the old story: “I will not meet the men as an organization but only as individuals. Motorman Lavin, not President Lavin.” Hedley had remarked in the 1916 strike that he would spend money like a drunken sailor to smash a strike and prevent real trade union collective bargaining. Then he had sent spies as far west as San Francisco to frame up letters attempting to discredit Bill Mahon. He was just as lavish in 1 926. The criminals and “green men’* who tried to run the trains received the sum of $1 an hour 24 hours a day. During the weeks that preceded the strike, Quackenbush attended all the important meetings of the Brotherhood and practically dictated its policies, including the order suspending all meetings during the strike.

That union was not strong enough, those men were not experienced enough to stand up under such a fire. Those earnest and sweet-hearted liberals who like to tell us about the experience and training gained by workers under company unionism should have been close to this scene instead of at their summer homes. They would have seen as helpless a group of robots as were ever produced by welfare-paternalism in the machine age. A blind, stubborn, splendid, good-natured, unorganized, buoyant, blundering revolt of those who for ten years had been blinded and bankrupted by company unionism at its worst. A concrete lesson in the “industrial self-government” the personnel managers and experts have been preaching about. Here was a good opportunity to observe the “functional freedom and responsibility” extolled by the proponents of “employee representation.” The company propaganda and strike-wrecking machine hit on all cylinders as it drove upon the workers and made splinters of their solidarity. The workers in revolt simply had no machine. They halted and turned and groped and eagerly accepted advice from all and sundry. They fought with both hands tied behind them but they fought magnificently considering the psychological bonds that had bound them to “the company.” But the muscles of “freedom and responsibility” had not been exercised. They were flabby, unskilled, helpless, inept.

But the workers could tell their story to those who asked them about the company union peonage. They turned some light on the conditions out of which they had torn themselves if only for a moment. They told of the discharge and the blacklisting of workers who had dared to raise their voices against the company and the tools on the “Brotherhood” staff. They told of workers suppressed and hounded and spied upon for having ideas about more wages, shorter hours and human freedom.

The strike proved all that the strikers said about the company union officials. Connolly, the President, forbade the workers to hold meetings during the course of the conflict, ordered the police to break up meetings of the few who had the courage to meet, parroted the Words of Hedley and the I.R.T. publicity department, reported to 165 Broadway the names of workers caught distributing circulars, dispatched spies to watch all gatherings and to report to the company those who proved “disloyal”; he even checked off for discharge workers showing sympathy with the strikers. He diligently cultivated “company morale.”

And what a background of “cultivation” on which to build this strikebreaking machine. Consider some of the elements in the shaping of workers’ loyalty channels during the last decade. One gets the picture by glancing over the Interborough Bulletin, founded in 1910, circulation 18,000, free to every worker, distributed by company guards at the terminals. In the back issues of this journal one begins to understand the factors in the game of “selling” the company to the employees. We pick items at random:—“Evidence of the great work done by the I.R.T. Brotherhood may be seen in the various communications received by its President, Mr. P.J. Connolly.” One is a letter from a worker thanking the boss of the union for getting him a job in the 129th Street shops of the corporation. Such service, performed by a regular trade union, would be “all in the day’s work,” but Mr. Hedley, under those conditions, would call it “agitation by outsiders.”

On another page called “Brotherhood Notes,” written by a gent who signs himself “Jocund,” we find that Mr. Connolly is in receipt of a postal card of thanks from a widow, which is all very splendid and convincing “union activity,” and perhaps more useful than attending complimentary dinners for President Hedley at the Hotel Commodore—a company union delegate’s reluctant duty!

A letter from the delegates of Local 9 announcing that they are again running for office and warning their constituents:

“Do not be swayed by the opinion of some one who may have expressed a misconstrued idea of some delegate, for we must realize if God cannot satisfy everybody then, therefore, we as men who are only mortal beings surely cannot overcome the wisdom of our Supreme Ruler…Again thanking you for your past favors and trusting to be of service to you for another term, we remain.”

After certain delegates to the company union are thus permitted the pages of the Bulletin to blame their mistakes on God and to ask for another term they usually get elected and come back with a letter of thanks after the ballots are counted. One of them “desires to thank all his fellow workers for their hearty cooperation and support and for the vim and eagerness they showed in standing by him.”

In between the election notices, pictures by the hundreds. Of babies—the “finest on earth”—of brides and delegates and soldier boys and harmonica players. Every employee must at sometime have his picture appear in the company magazine under such happy titles as Girls Take Notice, A Ladies Man, Has Passed Away, Likes His Job, Loves the Interborough, Some Picture, Faithful Employees, They’re Married Now, Well, Well, Well, Enjoying a Pension, Oh Girls Look, Likes His Bulletin, Girls, He’s Out Agin, Subway Agent Draws Triplets, Anyone Love Me, Caught in the Act, All Smiles, Hey There We See You, and commonest of all A Beau Brummel. (God, what a lot of these there are in the Interborough service.) And if we can’t get your picture, boys, we’ll insert your name. “Before the year is over we should like to see the name of every employee appear in the Bulletin and are sure you would like it too.”

Headline: “Thank President Hedley for Santa Claus Contest Prizes,” with a picture of the handsomest infant prize winner and a personal letter to the child from Frank himself. (Hedley once remarked, “I’ll go the limit on this welfare work.”) Also a letter of approval from the New York Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution on the assistance given by the company in the celebration of Constitution Day, especially through the sentiments expressed in the Subway Sun, the “wall newspaper” of the I.R.T. management.

Editorial observations of the Bulletin are always penetrating. One of them on the occasion of the death of the late Harding:

“Surely this is a land of astonishing opportunity for the workingman.”

What? Even under the yellow dog? Then commenting on the careers of Messrs. Wilson, Harding and Coolidge:

“If there’s any reason why an intelligent, honest and hustling young conductor or motorman of the Interborough Rapid Transit Company shouldn’t live to become President of the United States it’s not obvious.”

One pride of the company is the Subway Band. The Bulletin informs us that this band has been also the official band of the Loyal Order of Moose of which “the Hon. James J. Davis is the head.” Secretary Davis once praised the band boys in a letter to the president of the company:

“I was especially impressed with that band of yours. You can well be proud of having fathered and fostered it to its present glorious efficiency.”

Ironically enough this band is said to have rendered with particular charm Prof. Goldman’s famous march, “Chimes of Liberty.”

Of course there are other departments in the Bulletin: Pleasing the Public, Music, Woman’s Sphere, Our Novelty Page, Sports, Bulletin Tots (baby pictures again) and the Subway Honor Roll, as well as generous interviews with those who have retired on pension after 50 years underground between the Bronx and the Battery.

There may also be just a word or two given in the Bulletin to the sordid matter of wages. This is usually introduced by Mr. Hedley with a few lines on the perennially bankrupt state of the company followed by about 100 words telling readers that Mr. Connolly and Mr. Hedley exchanged letters on the subject and that wages will remain “as is” for another twelve month. The real Brotherhood Notes in the same issue may be expansive on the Annual Outing and Picnic, the wonderful Colored Employees’ Ball or some other “Banner Night” or “Get-together Evening for Lonesome Hearts” at the company’s expense.

Articles in the Bulletin cover a wide range of interest but nothing concerning the working class or trade union organization is permitted. “Why the Organization of the Interborough Employees is Boosting a Six Cent Fare” was a piece by a former company union president. And at a later period “A Memorial on the Seven Cent Fare” was appropriate. Or an oration by Martin W. Littleton, Esq., on the glories of private ownership and the iniquities of the public ownership advocates who are accused of “polyglot radicalism.” Followed by an article on “Boosting Business for your Company,” Mr. Hedley on “Loyalty,” and Andrew Mellon, himself, on “Success.

***

This is the background against which the motormen and their followers revolted, the atmosphere into which they have been driven back. And this is the contract the “free agent” and untrammeled citizen who works for the welfare-cursed Interborough must sign when, in the exercise of his exalted free will and glorious personal liberty, he elects to work 84 hours a week as a stationman for 41 cents an hour, or for 69 cents an hour as a motorman, or for 58 cents an hour as a switchman. This is the symbol of the I.R.T. company union, the contract used under the sharing of management relationship hallowed by the New York Times. Step up to the employment desk, brother worker, and sign on the dotted line:

“In conformity with the policy adopted by the Brotherhood and consented to by the Company (the poor company just had to consent to what the Brotherhood adopted—RD) and as a condition of employment, I expressly agree that I will remain a member of the Brotherhood during the time l am employed by the Company and am eligible to membership therein;

“That I am not and will not become identified in any manner with the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employes of America, or with any other association of street railway or other employes with the exception of this Brotherhood and the Voluntary Relief Department of the Company while a member of the Brotherhood or in the employ of the Company.

“And that a violation of this agreement or the interference with any member of the Brotherhood in the discharge of his duties or disturbing him in any manner for the purpose of breaking up or interfering with the Brotherhood shall of itself constitute cause for dismissal from the employ of the Company.”

***

In 1916 the I.R.T. put over this contract and broke the strike of the A.F. of L. union against it. Since 1917 nothing has been done to win the workers away from company unionism and the welfare strangle hold. When the eruption came on Independence Day, 1926, the A.F. of L. union, the Amalgamated, put out feelers for the affiliation of the rebels. Everyone in the strikers* confidence, except a few cynical sectarians, advised them to link up with the American labor movement as represented in this union. But the men were hesitant and uncertain and preoccupied. Divided opinion among the leaders resulted in delay. Finally when they came into conference with the Amalgamated representatives the strike outlook was less hopeful and the men report they were handled like babies and given little encouragement. This attempt to get together was apparently half-hearted on both sides, but the blame rests chiefly with the older and more experienced men of the Amalgamated who failed to help the strikers with advice, counsel or leadership. The representatives of this international seem to have little of the flaming spirit that nearly brought a general strike on New York City in 1916. Like other A.F. of L. officials they appear afraid to come in contact with vital, fighting elements among the workers, even though, as in this case, most of them be Irish! However, we have no reason to believe that, had the strikers joined the A.F. of L., they would have been more tenderly handled by Mr. Hedley. Indeed, if we are to judge by the tactics of 1916, they would have been even more feared and probably as ruthlessly crushed by the anti-all-labor dictatorship on the I.R.T. The strike ended as usual with a wholesale discharge of the leaders, despite the company’s verbal agreement to take them back.

The failure of the revolt leaves the company union and the Quackenbush-Hedley-Connolly Triumvirate in control, with the “Brotherhood” boosting the company, knocking the five cent fare, printing the baby’s pictures and otherwise fooling, bulldozing and robbing the workers till the next revolt breaks out. When that will be depends on how much manhood and independence survives the next wave of welfare slush that sweeps through the subways and over the L’s.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s to early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway, Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and more journalistic in its tone.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1926/v01n05-sep-1926-New-Masses-2nd-rev.pdf