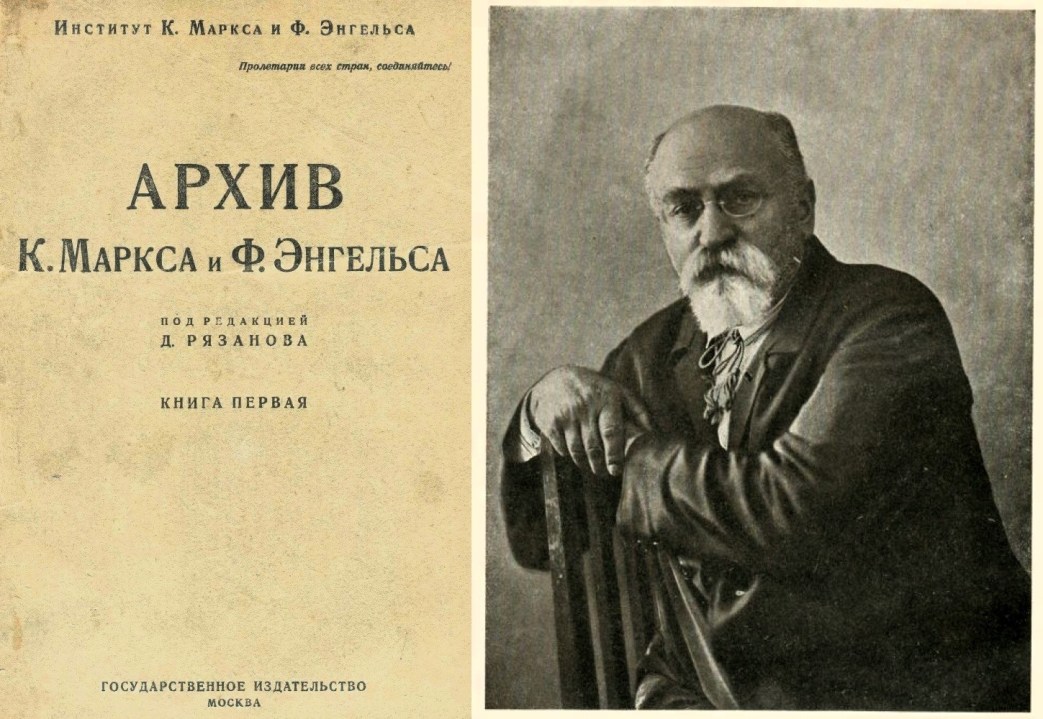

David Riazanov, head of the Marx-Engels Institute which sought to collect, contextualize, and publish the extant workers of Marx and Engels, on the riches between the covers of the inaugural issue of the Institute’s journal, ‘Archive’. A link to the original 500-page magazine, in Russian, here. As the below makes clear, Riazanov’s many introductions and notes in the magazine would make for a worthy translation project.

‘The Marx-Engels Archive’ by David Riazanov from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 8. January, 1925.

In the land of the dictatorship of the proletariat, life pulsates with creative effort; a new society is being constructed; inquiring minds, with fresh cultural powers are zealously ahead to create a new civilisation. The intellectual instrument of the proletariat in the land where it defeated the bourgeoisie on the battlefield with physical weapons, had to find an intellectual workshop worthy of its victory. Marxism, the science of the proletariat, found its most favourable environment in Soviet Russia. Not in Germany, where our great teachers, Marx and Engels, were born and brought up; not in France and England where they lived, fought and studied almost all their lives, was it possible to establish that worthy intellectual workshop for fashioning the intellectual heirloom of our great teachers, but here in Moscow, in the heart of proletarian Russia. The Marx and Engels Institute is a powerful instrument in this work. Not in German, the native language of Marx and Engels, but in Russian, the language of the first victorious proletariat, are the hitherto unpublished manuscripts of Marx and Engels published and the commentaries on the works of Marx and Engels being written. The international proletariat will have to wait until the great idea intended for the proletariat of the whole world are re-fashioned into the native language of Marx and Engels.

The first number of the Archive, published by the Marx and Engels Institute now lying before us is a most valuable contribution to Communist scientific literature. We do not undertake, in this brief review, to deal exhaustively with its rich contents. Principally we desire to draw the attention of the reader to what is new in this number, of the unpublished manuscripts of Marx and Engels, namely, “German Ideology,” by Karl Marx, and “Correspondence with Bernstein,” by Engels. We repeat that the contents of this issue is extraordinarily rich and a series of articles would be required to bring them fully to the notice of the reader. Our modest task, however, is merely to draw the reader’s attention to the enormous value of the material and arouse in him the desire to study for himself this intellectual treasure—mainly consisting of the works of Marx and Engels.

“German Ideology” published for the first time in this Archive, throws a brilliant light upon the development of Marx’s idea in the realm of philosophy. In this manuscript written in Marx’s earliest years we have, as Riazanoff observes, The first exposition of the materialist conception of history. One of the principal ideas in the purely philosophical part of this manuscript which should be observed, is Marx’s view on the place of philosophy in the ranks of the sciences. Riazanoff is quite right when he says:

“The manuscript published enables us to establish another important fact for the scientific investigation of the philosophical evolution of Marxism. The conclusion with which we met in ‘Anti-Deuring’ had been formulated already in the manuscript on Feuerbach, Philosophy as a special science of the universal connection between things and knowledge as a summa summarium of the whole of human knowledge, becomes superfluous. Of all previous philosophies there remains only the science of the laws of thinking, formal logic and dialectics.”

Here we find further a formulation of the relation between consciousness and environment, recalling a famous passage in “Critique of Political Economy.” Pointing out that ideology is not independent and cannot have an independent history, because history in a scientific sense deals only with human beings developing their material production, Marx says:

“Thus ethics, religion, metaphysics and other forms of ideology and the forms of consciousness corresponding with them, lose their apparent independence. They have no history, no development: only human beings developing their material production and their material intercourse in this process also change their thinking and the product of their thoughts. Consciousness docs not determine life, but life determines consciousness. The first method of investigation regards consciousness as a living individual; the second which corresponds with real life starts out from the real live individuals themselves, and regards consciousness only as their consciousness.”

Marx’s view on philosophy as a special science, or as he describes it, as a “summa summarium” of all sciences, in my opinion, is a fundamental idea of Marx and Engels which abolishes once and for all the traditional role of philosophy and recognises only formal logic and dialectics, and much more attention should be paid to it than is done at present by our Marxians. The Marxian method should be applied in a greater degree than hitherto in fields to which up till now Marxists have devoted relatively little attention, such as ethnography, history of civilisation, art, religion, psychophysiology, etc. It should be applied as a fundamental method for scientific understanding of psychical phenomena, and less attention should be devoted to pure philosophy, i.e., philosophy isolated from living science.

In a wonderfully apt and profound criticism of passivity in Feuerbach’s Materialism, Marx in this manuscript gives another rendering of his famous thesis against Feuerbach, viz., “Philosophers in different ways merely explained the world, but, the task is to transform it.” He puts it this way:

For a practical materialist, i.e., for a Communist, 1it is a question of revolutionising the existing world to turn practically against things as he finds them and change them. Although such views are sometimes expressed by Feuerbach, nevertheless, they are always in the stage of disjointed guesses which have so little influence on his general philosophy that they can be regarded here only as means to facilitate the development of embryo. Feuerbach’s conception of the physical world is limited by bare sensations. (There is a note in Marx’s handwriting as follows: ‘taking “humanity as a whole” instead of “the real historical man.” This “man” is realiter a “German.”’) in the first case an investigating the physical world he inevitably comes up against things which for his consciousness and his senses disturb the harmony which he assumes exists between all parts of the physical world, and particularly between man and nature.”1

In order to remove this, he is compelled to seek salvation in a kind of dual conception by making distinction between a common, everyday conception which sees only that which “is under one’s very nose” and a higher philosophical conception which sees the “true essence of things.” He does not observe that the physical world surrounding him is not a thing eternal and unchangeable, but a product of industry and social state, a product in the sense that in every historical epoch it is the result of the activities of a number of generations, each of which stands on the shoulders of the generations preceding it, developing its industry and its means of intercourse, and in accordance with the changes in its requirements, changes its social structure. Even the simplest things of “palpable authenticity” exist because of social development, because of industry and commercial intercourse.

What attracts one’s attention in this is Marx’s deeply though out activity. Marx demands activity of a philosopher, that he fight against things. Only by action does man understand the world, and all thought isolated from action must suffer from a fatal defect. Man when acting, changes nature, i.e., changes the physical world which surrounds us, and this Feuerbach failed to understand. Further analysing the function of consciousness and its apparent independence, Marx points out that only by dividing labour into physical and mental is consciousness enabled falsely to expound its own significance, Marx says:

“Division of labour really becomes such only when a division into physical and mental labour takes place. From that moment consciousness may really imagine itself to be something different from the consciousness of existing practice. From the moment that consciousness begins really to represent something, without representing something real, it is able to liberate itself from the world and proceed to form “pure theory,” theology, philosophy, ethics, etc., but when this theory, theology, philosophy, ethics, etc., comes into conflict with existing relations it is due only to the fact that the existing social relations have cone into conflict with the existing forces of production. Among certain nations this may also be a result of these antagonisms revealing themselves not within their own national frontiers, but between national consciousness and the practice of other nations, i.e., between the national and the universal consciousness of a nation (as for example in Germany to-day). If these antagonisms appear to a certain nation in the form of antagonisms within the national consciousness, then the struggle apparently is also limited by this national trash (Scheise); because that nation in itself is nothing but trash.”

One would like to quote much more, in fact all, for at every step one meets profound thoughts. Unfortunately, we cannot do this here and in leaving, for the time being, this great work of Marx, we quote the following passage dealing with the function of tradition, dragging at the individual and retarding the process of creating a new ideology corresponding with the change that has taken place on the economic basis.

“From this it follows that even within the precincts of a single nation certain individuals—even abandoning their property relations—go through completely different processes of development and that the preceding interest—a special form of relations which has been substituted by a form of relations corresponding with newer interests—long continues by tradition to predominate in the illusory collectivity (state, law), which objectively us opposed to the individual, a predominance which in the last resort can be destroyed only by revolution.”

We heartily recommend this work of the genius Marx, to all those who are interested in the burning questions of the theory and practice of Marxism.

We will now turn to the correspondence between Engels and Bernstein. This correspondence served as a collection of historical documents of first class importance, Engels—statesman, profound tactician and Marx’s best friend—stands out before us in remarkable relief. No matter whether he is dealing with the internal history of German social democracy, with the most complex questions of tactics and programme—like the national question in the Balkans, in connection with the complications arising in the relations between Austria and Russia in the ’eighties—whether he is dealing with the history of the French Socialist Party, the gradual development of the revolutionary struggle and the tactics of that struggle, or even with the question of what importance a given political system under capitalism has for the proletariat, Engels always reveals that wonderful aptitude and clearness, his youthful enthusiasm, his firm, unhesitating, consistent revolutionary line of thought, his great versatility, conscientiousness even in petty things, and a surprising diligence that is characteristic of him. To this should be added a brilliant wit, and a sense of humour which runs throughout the whole of this correspondence and makes the reading of it a real joy. Engels stands before us full of life and energy, an irresistible, full-blooded, revolutionary fighter. Here, too, we would like to quote without end, but alas, this is impossible. Nevertheless, we cannot refrain from quoting the following passages. Here is an excellent passage from a letter dated 18th of January, 1883:

“We were very pleased with the replies of Grillenberger and S.D. to the hypocrisy of Putskamer. That is the proper way to deal with them. One must not squirm under the blows of the enemy and howl and sob and plead excuses that no harm was meant, as some do. For every blow of the enemy we must return two and three; this has been our practice for ages, and I think that up till now we have fairly well beaten the enemy. ‘The spirit of our troops rises in attack, and this is as it should be,’ says old Fritz in his instructions to his generals, and the same thing can be said of our workers in Germany. But what if Kaiser, for example, during the debates on all the exceptional laws (assuming Ferick’s extracts to be correct) retreats and whines that we are revolutionaries only in the Pickwickian sense? What he should have said was that the whole Reichstag and the Allied Council exists only as a result of revolution, that when old Wilhelm gobbled up three thrones and a free town, he was also a revolutionary ; that all this legitimacy, all this so-called foundation of the law, is nothing more or less than the product of innumerable revolutions carried out against the will of the people and directed against the people. Oh! This damned German flabbiness of will and thought which was with such difficulty introduced into the Party simultaneously with the ‘intellectuals’! Oh, if we could but get rid of it once and for all.”

This is how the fighter Engels argues. Reading these lines unconsciously the figure of another genius and fighter of the same type rises up in one’s mind—Lenin.

How apt and full of wit is the commenting on Rodbertus in the letter dated 8th of February, 1883.

“We shall be very grateful to you for the book by Rodbertus—Meyer. This man once nearly discovered surplus value, but his Pomeranian estate prevented him from so doing.”

And now another very characteristic passage from the letter dated 20th of October, 1881:

“The ‘Proletaire’ people are those who say that Guesdes and Lafargue are merely the echoes of Marx which, expressed in ordinary, everyday language, means ‘Ils veulent vendre les ouvriers Francais aus Prussiens et a Bismarck’ (They desire to sell the French workers to the Prussians and to Bismarck) and M. Malone very clearly reveals this attitude in all his works, and it must be said, in a very unworthy manner. Malone strives to ascribe the discoveries of Marx to other persons (Lasalle, Schéffle and even to De Pape). Of course it is quite in the order of things that there should be differences of opinion with party people, whoever they may be, with regard to their conduct under given circumstances or to disagree and argue with them concerning some theoretical point. But to argue in this fashion against the most original achievements of a man like Marx reveals a pettiness of mind possessed only by printers’ compositors, whose conceit you know very well from your own experience. I cannot understand in the least how one can envy genius; this is something so peculiar that we who do not possess it know beforehand that it is inaccessible to us; but one must be very petty indeed to be envious of it.”

The friendship that existed between Marx and Engels has not yet been properly estimated, and yet this friendship is on a par with those remarkable examples of friendship between individuals that have occurred in history. The fascinating personality of Engels stands out in this friendship with remarkable clearness, for it was Engels who gave and sacrificed most. He devotedly sacrificed everything. Not only did he daily save Marx from death from starvation by his untiring aid, not only did he write articles for and on behalf of Marx, not only did he, all his life, zealously defend his great friend and colleague at every step, but more than that he devoted the whole of his genius to the service of his friend. Himself a great thinker, for many years he voluntarily refrained from scientific labours and toiled at dull and tiring office work in Manchester, merely to be in a position to provide for Marx’s material wants, and he did this in the most simple and modest manner. He always desired to keep in the background and always regarded Marx as being immeasurably superior to him in intellect. Engels made the sacrifices not out of personal sentiment, but for the sake of the cause which both he and Marx served, and which Engels describes to us in all its beauty. And this is evidenced by the correspondence now published.

The first number of the “Archive” is dedicated to Lenin. It is worthy of this great name. We wait with impatience for the publication of future numbers of this most valuable magazine.

1. Feuerbach’s mistake was not that he subordinated sentient Perception lying under his very nose to sentient reality established by a more or less precise study of palpable facts, but that in the last resort, he cannot approach perception without the “eyes,” i.e., the “spectacles” of a philosopher.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n08-feb-1925-new-series-CI-grn-riaz.pdf