Fascinating and valuable account of the background to Engels’ most important essay on the U.S. workers movement by Marxist historian Avrom Landy. Written as a preface to a newly translated edition of his ‘Condition of the Working Class in England’ by Florence Kelley Wischnewetzky in 1892, the text was influenced by Eleanor Marx’s trip to the United States. Landy provides the context to Engels’ thinking and his correspondence with Kelley as well as other Americans.

‘Engels on the American Labor Movement’ by Avrom Landy from The Communist. Vol. 7 No. 5. May, 1928.

IN HIS preface to the London, 1892, edition of “The Condition of the Working Class in England,” Engels tells us that this book “was first issued in Germany in 1845…” “It was translated into English,” he continues, “in 1885, by an American lady, Mrs. F. Kelley Wischnewetzky, and published in the following year in New York. The American edition being as good as exhausted, and having never been extensively circulated on this side of the Atlantic, the present English copyright edition is brought out with the full consent of all parties interested.

For the American edition, a new Preface and an Appendix were written in English by the author. The first had little to do with the book itself; it discussed the American Working Class Movement of the day, and is, therefore, here omitted as irrelevant, the second—the original preface—is largely made use of in the present introductory remarks.”

Nevertheless, irrelevant in an English edition, this preface was considered of sufficient importance in this country to be published separately as an eight-page pamphlet entitled “The Labor Movement in America.” This was done, the publishers tell us, “in order to make it accessible immediately, to the largest possible number of readers, since it bears directly upon the condition of the labor movement in America at the present time.”

Although Engels’ book and pamphlet were published in 1887, it was not long before they had both practically disappeared from the market. In 1892, Engels himself states that the American edition was as good as exhausted. Since then, only the English copyright edition of 1892 has been available to the general public. The American edition, together with the Preface reprinted in pamphlet form, have been completely forgotten and can now be found only in special libraries or private collections.”

In itself, the edition of 1887 is no different from that of 1892. But the preface, dealing with the labor movement in America, and the correspondence between Engels and his translator connected with the entire project, are of the utmost importance to present-day Marxists in America.

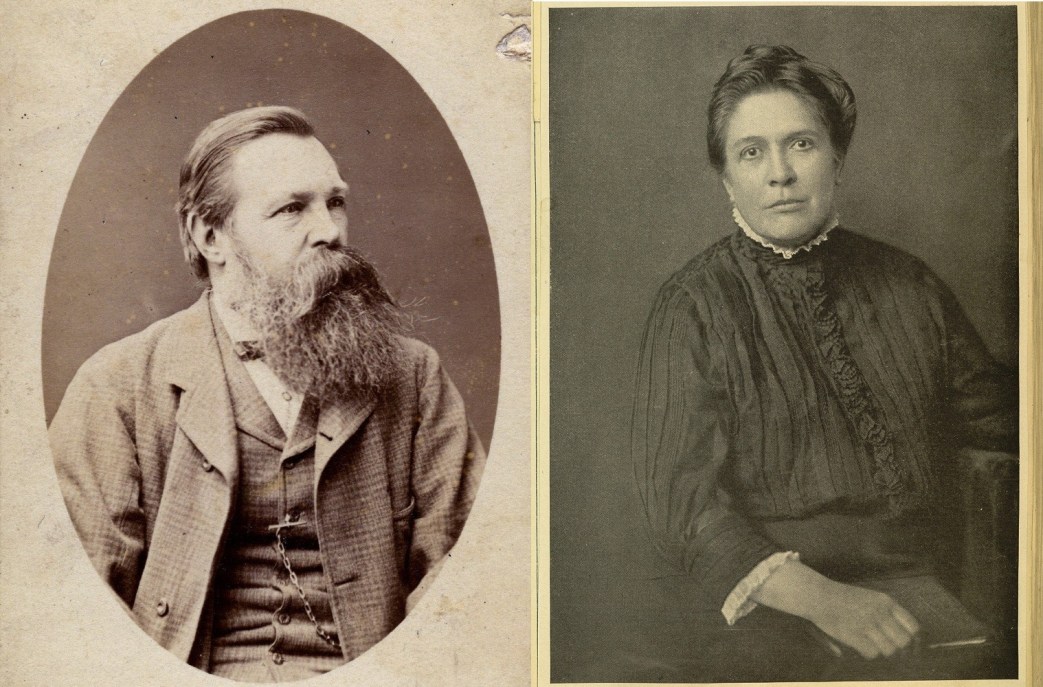

Although Mrs. Wischnewetzky had completed the translation of Engels’ book towards the end of 1884, having entered into negotiations with him by the beginning of 1885, it was not until 1887 that the book was finally published. Shortly before publication, however, in November, 1886, she wrote to Engels, requesting a special preface for the American edition. This, Engels was ready to furnish, especially since he felt that with the recent developments in the American labor movement a preface would be very much wanted. Furthermore, Edward and Eleanor Marx Aveling, together with Wilhelm Liebknecht, having been invited to make a tour through America under the auspices of the Socialist Labor Party, Engels expected a certain amount of reliable first hand information, which he intended to use in the composition of his preface. He therefore replied to Mrs. Wischnewetzky on December 28, 1886, offering to comply with her request. A month later, the Preface was on its way to America, having been forwarded to Mrs. Wischnewetzky the 27th of January, 1887.”

This is scarcely the place to raise the question of Engels’ sources of information. Nevertheless, the extent to which Engels was influenced by the Avelings in his estimation of the American situation may be touched upon briefly here. In his reply to Mrs. Wischnewetzky’s request for an American preface, Engels insisted that he would have to “await the return of the Avelings to have a full report of the state of things in America” before he could write the required prefatory remarks. A comparison of Engels’ preface with the articles on “The Labor Movement in America” which the Avelings published in the London Monthly Time and later republished in book form, shows clearly that the Avelings had been a source of information to Engels, Furthermore, Engels himself had admitted that he had learned much from the Avelings concerning the labor movement in America. Nevertheless, it must not be assumed that the Avelings were more than a source of information to Engels and that he did not have an independent view on the movement in the United States. One need only compare Engels’ preface with the Avelings’ book to realize who is the master and who the pupil.

Furthermore, as I have tried to show in an article on Marx, Engels and America, published in recent numbers of the Communist, Marx and Engels had always, from the early forties on, kept close touch with development in America, because of the latter’s peculiar position in the world economy of the time, and consequently, because of its important relation to the development of the revolution in Europe. Indeed, Engels’ preface and his views on the American labor movement at this time must be considered as a part of this far from accidental and fundamentally revolutionary interest in America—if their full significance is to be grasped. From first to last, Engels’ interest in America was the relation it bore to the Revolution in the different stages of its development. With Marx’s death, Engels had become the sole guardian of the world revolution, as it were, watching closely and carefully every new development, no matter where, registering every movement bearing upon the Revolution, whether in agrarian America or reactionary Russia Already in 1882, a year before Marx’s death, the old masters had recorded the momentous changes which had taken place in these two countries, expressing the opinion that a successful revolution in Russia might even become the signal for a revolutionary wave in the west.

What the Avelings brought Engels, therefore, was merely additional information which strengthened his own conviction in regard to the movement in America. Engels himself has pointed out that his interest in this country and his views on the labor movement here were continuous and independent. In reply to a fear expressed by Mrs. Wischnewetzky that he had been unduly influenced by Aveling, he stated: “Your fear as to my being unduly influenced by Aveling in my view of the American movement is groundless, as soon as there was a national American working class movement independent of the Germans, my standpoint was clearly indicated by the facts of the case. That great national movement, no matter what its form, is the real starting point of American working class development. If the Germans join it, in order to help it or to hasten its development in the right direction, they may do a deal of good and play a decisive part in it. If they stand aloof, they will dwindle down into a dogmatic sect, and will be brushed aside as people who do not understand their own principles. Mrs. Aveling who has seen her father at work, understood this quite as well from the beginning, and if Aveling saw it too, all the better. And all my letters to America, to Sorge, to yourself, to the Avelings, from the very beginning, have repeated this view over and over again. Still I was glad to see the Avelings, before writing my preface, because they gave me some new facts about the inner mysteries of the German party in New York…”

More than a year before the Avelings undertook their tour through America, Engels had consented to an American edition of his youthful work because, in his estimation, conditions in America at that time corresponded “almost exactly to the English conditions of the forties.” ‘To what an extent this is the case,” he said in a note to the German translation of his American Preface, “is testified to by the articles on “The Labor Movement in America’ by Edward and Eleanor Marx Aveling, in the London Monthly Time, for March, April, May and June.”

That the report of the Avelings merely strengthened Engels’ own conviction in regard to the American labor movement, is therefore made clear by the Avelings themselves when they write: “…He that will compare the picture drawn by F. Engels of the English Working Class in 1844 will see how absolutely parallel are the positions of the English workers in 1844 and the American in 1887. With this difference. “The American has the forty years’ experience of his European brethren to teach him, and as Engel says, in America it takes ten months to do what in Europe takes ten years to achieve. Every word of Engels’ Introduction, chapter after chapter, page after page of his book, by the simple substitution of ‘America’ for ‘England,’ and ‘American’ for ‘English,’ apply to the United States of today, and thanks to these forty years’ experience, thanks to the higher development of the capitalist system, the concluding words of Engels’ work are especially true of the America of our time. “The classes are divided more and more sharply, the spirit of resistance penetrates the workers, the bitterness intensifies, the guerilla skirmishes become concentrated in more important battles, and soon a slight impulse will suffice to set the avalanche in motion.’”

To Engels, the most important fact about the labor movement in America at that time was the circumstance that vast masses of working people, moving spontaneously and instinctively over a vast extent of the country, as he said, had become “conscious of the fact, that they formed a new and distinct class of American society; a class of—practically speaking—more or less hereditary wage-workers, proletarians. And with true American instinct this consciousness led them at once to take the next step towards their deliverance: the formation of a political workingmen’s party, with a platform of its own, and with the conquest of the Capitol and the White House for its goal.”

This is the recurrent theme of Engels’ letters to Mrs. Wischnewetzky, to Sorge, to Herman Schluter, and, as he says, to the Avelings during their American tour. A great national movement, no matter what its first form, class consciousness and a national labor party are the first conditions for the achievement of the proletarian dictatorship. In this movement the Communists may participate and play a decisive part, or they may stand aloof, and dwindle down into a dogmatic sect, only to be brushed aside as people who do not understand their own theory. It is forty years since Engels first gave this advice to American Marxists; it might just as well have been given to us today.

There are “Marxists” in America who will see in Engels’ preface a complete renunciation of armed insurrection and “the dictatorship of the proletariat.” What has a labor party, whose goal is the conquest of the Capitol and the White House, to do with dictatorship? Has not Engels made it plain that the American revolution will be achieved, not by armed insurrection, but by means of the voting power of the American working class? It is unnecessary to point out the unmarxian, undialectic approach to the question involved in this formulation. Nevertheless, it will not be out of place to repeat that at no time did Engels degrade his revolutionary Marxism to a social-democratic parliamentarism. In raising the slogan of a labor party for America, he was merely insisting upon a principle which he and Marx had followed consistently for more than forty years. An independent party of workers was definitely a Communist slogan and the ‘abc’ of Communist practice; it existed side by side with the principle of armed insurrection, leading to the dictatorship of the proletariat, and not in opposition to it. This, only the traitorous reformism of a Social Democracy could question.

In the same year that Engels raised the slogan of a labor party in America, he published the second edition of his “Housing Question” in which he unequivocally states: “Every real proletarian party, from the English Chartists on, has always set up class politics, the organization of the proletariat as an independent political party as its first condition, and the dictatorship of the proletariat as the immediate goal of the struggle.”

We see that Engels makes a clear and definite distinction between the first condition and the immediate goal of the struggle. Unless the condition is fulfilled, the goal cannot be achieved. It is a fundamental Marxian principle that the immediate goal of the class struggle is the dictatorship of the proletariat, but the first condition for the achievement of this goal is the organization of the proletariat into an independent political party. Not only is there no opposition here between the immediate goal and the first condition of the struggle; but Engels states expressly that the organization of a labor party is only the first condition of the struggle, not the exclusive means or the sole condition of the revolution. We are thus dealing, not with a reformist parliamentarism or even a diluted Marxism, but with a clear-cut policy as to the actual conditions for the achievement of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The organization of a labor party, however, did not, in Engels’ opinion, do away with the need for a Marxist, Communist Party. American Marxists, he insisted, can play a decisive part in the formation and leadership of the labor party—if they understand their own theory; if they realize that their theory “is not a dogma but the exposition of a process of evolution, and that process involves successive phases. ‘To expect that the Americans will start with the full consciousness of the theory worked out in older industrial countries is to expect the impossible. What the Germans ought to do is to act up to their own theory—if they understand it, as we did in 1845 and 1848—to go in for any real general working class movement, accept its actual starting point as such and work it gradually up to the theoretical level by pointing out, how every mistake made, every reverse suffered, was a necessary consequence of mistaken theoretical orders in the original programme: they ought, in the words of the Communist Manifesto “represent, in the present of the movement, the future of the movement.”

“I think all our practice has shown that it is impossible to work along with the general movement of the working class at every one of its stages without giving up or hiding our own distinct position and even organization, and I am afraid that if the German Americans choose a different line they will commit a great mistake…”

The national extent, the large influence, and the “democratic and even rebellious spirit” of the Knights of Labor, representing the movement of a “fermenting mass” within the working class, made it appear as if, in a very short time, the American workers were going to achieve the first steps towards their emancipation. To Engels, this was a mighty and glorious movement, full of promise for the future and the proletarian revolution, “the raw material out of which the future of the American working class movement, and along with it, the future of American society at large, has to be shaped.” He could not know, as we know today, that it was the newly organized American Federation of Labor and not the fermenting Knights with a membership running far beyond half a million, that was to become the main stream of the American labor movement. Engels did not live to see the vast, spontaneous movement of the eighties directed into the narrow, petrifying channel of present-day trade union politics. He did not know that, to a certain extent, the movement then would be in advance of the movement today; that today, we would still have the first two elementary steps towards proletarian emancipation to achieve—to be sure, on a more advanced technical plane and on a higher stage of capitalist development.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March ,1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v07n05-may-1928-communist.pdf