Tom Tippett, who spent years covering West Virginia miners, delivers us this stirring account of 1932’s Hunger March in that state led by legendary radical miners’ leader Frank Keeney and his West Virginia Mine Workers’ Union.

‘Hungry Miners March In Charleston’ by Tom Tippett from Labor Age, Vol. 21 No. 7. July, 1932.

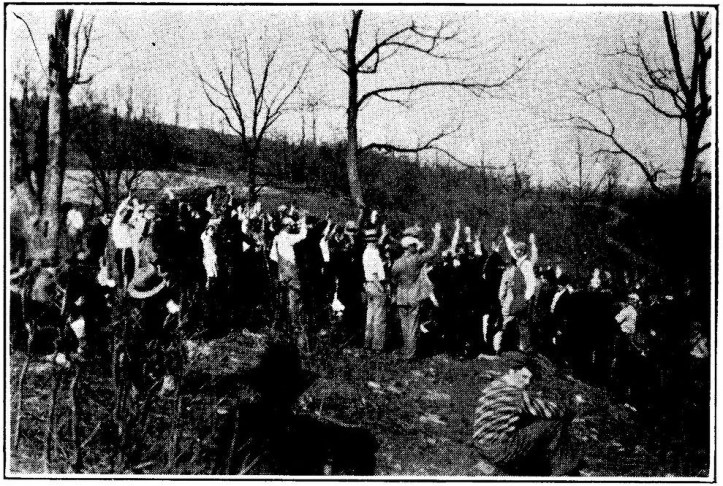

Kanawha Valley of West Virginia foiled the police to assemble and then defied them, to conduct an unemployment demonstration in the state capitol city of Charleston on June 4. The demonstration continued until the night of June 9. Each day its ranks were increased by additional hungry men and women and in the end they won. This does not mean that the hunger and unemployment problem is settled down here but it does mean that the demonstration opened up relief channels which had been closed to the miners and it halted the eviction of their families from their homes. Moreover, the hunger march caused the state of West Virginia to gather up the furniture of mine workers from a roadside tent colony and haul it back into the houses from which a coal company had evicted it the week before. The demonstrators belong to the West Virginia Mine Workers’ Union. Frank Keeney, president of the union, was spokesman for the hungry group. Last year the same group of miners marched in a hunger demonstration on Charleston, at the close of a strike conducted by the union. At that time, they were met at the city gates and prevented from crossing a bridge to the Capitol by armed members of the state police. This year the miners organized the demonstration secretly and entered the city in small numbers. They appeared en masse on the lawn of the State House before the police could organize against them. A hand bill had been distributed the night before the march throughout the valley. It was unsigned and read: “Notice: To the Miners and Other Starving Workers! Your Presence ts Expected in Charleston—State Capitol —on Saturday Morning—10 a.m. This Notice Means—You Be There! or Forever Stop Complaining of Hunger!” ‘The state police saw one of the bills and at dawn threw an armed guard around every entrance to the state house, and it remained through- out the week.

At the appointed hour, several hundred miners appeared suddenly at the capitol; along the routes to the coal camps other miners were trudging towards the city and the crowd increased by the hour. The police smuggled close to the doors of the building and increased their numbers as the mass grew in the yard. The city newspapers featured the story with a spread head: “Troopers Guard Capitol as Hungry Miners Gather.” This story penetrated the valley and more miners were thereby set on the march.

The state house is a new building scheduled to be dedicated this month. It is set in spacious grounds at the edge of the city on the banks of the Kanawha River; conspicuous for its exquisite design and expensive composition. It cost seven million dollars and intends to advertise that fact by a huge dome inlaid with gold leaf that added $23,000 to the price of its erection.

After the hunger demonstration at the city bridge last year there was so much complaint made of the golden dome, then under construction, and starving workers that the architect of the building came to town and said in the press that the gold leaf actually did not cost as much as it appeared. So the gold went on and thus it came about that this year the starving coal miners from whose labor West Virginia gets its wealth and power met to demand bread on the yard of their own capitol shaded from the heat by the golden dome which glimmered serene and beautiful in the sun.

The contrast was obvious and striking. These miners were hungry. They were ragged. The march had not been bolstered up or padded. For months and months they had waited in the camps, being put on and taken off various relief lists. Charity, as well as state and county funds were said to be exhausted. One mine after another had shut down; with them, the company stores had closed too. Hundreds of miners were living in tents, victimized workers from the mine strike last summer. Sickness was rampant in their families. They had appealed to this and that relief agency but their misery only grew: Then came a new batch of evictions in a camp called Gallagher. The Wacomah Fuel Company there caused the eviction of six families on June I. The heads of these families had refused to work, without wages, in the mine to cover their rent while their families ate as best they could from the intermittent relief furnished by the county welfare. Last January six other families had been thrown out of the same company’s houses and have lived ever since in tents furnished by the West Virginia Mine Workers’ Union. The new evictions raised the temper of the men. In still another camp at Whitesville, the mine closed, credit stopped at the store, and then a general announcement that the miners might have work for a flat rate of $2.00 a day—when the mine operated.

One wage cut after another was imposed throughout the valley and although miners were compelled to accept them, thousands of their number were unable to find work and those who were employed were so paid that their families starved before their eyes. All of them, naturally, were paid n company scrip and with it bought supplies at skyhigh prices in the “pluck-me” stores. It was no wonder then that when they saw a crude notice calling them to the capitol, they responded. Food was the topic of the hour. Miners’ women tramped into the demonstration with their children and many a coal digger there carried a baby in his arms. There were Negroes, too, and now and then an Italian or a Pole—a cross-section of the coal fields.

The miners elected a committee to carry their demands inside the marble building. At its head they placed Walter Seacrist, a young miner from Holley Grove who had just returned to his coal camp from Brookwood Labor College where he was a student since last year’s strike. The demands of the marchers were headed by one against the eviction business, another for food or work, another demanding that America as a whole recognize the principle that all workers are entitled to the right to earn a living, or unemployment relief without the tang of charity. The committee trudged up the steps of the State House, a Negro member among them, past the armed guard and into the office of Governor Conley. The Executive was absent, of course, but his secretary talked with the representatives of the mob for two hours. In the end he said, as the Governor had said last year, that West Virginia could do exactly nothing for its unemployed and he recommended that the marchers go home again and solicit aid from the employed miners. While the state was thus talking with its citizens within the palace the crowd swelled outside. It listened to speeches, bristling with fire. It blocked traffic of the most aristocratic street in town. It improvised banners which said a lot of things, the most unique of which were: “If we don’t get bread, we’ll take it”; “Starvation for coal miners—thousands of dollars for the dome”; “Millions for the Capitol while we Starve”; etc.

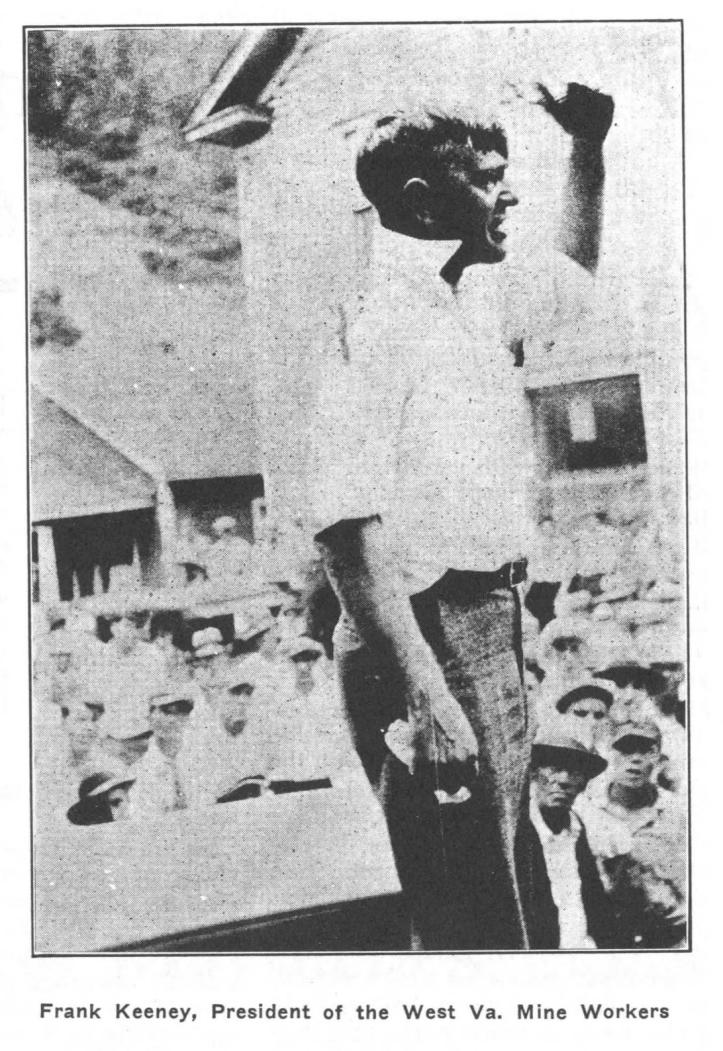

Keeney Speaks

The committee appeared, the crowd surged into the streets, Seacrist mounted the steps and told the story—“and I told him,” Seacrist concluded, “that if the state can’t help us, we are going to help ourselves!’ The crowd cheered and called for Frank Keeney. The president of the West Virginia Mine Workers pushed his way through the mob to the steps. In a speech that will live forever in the memory of coal diggers, Frank Keeney sketched the plight of workers in America. He has lived in the West Virginia coal belt all his life and all of that time he has been struggling with and for the coal diggers. It was an incredible story of human suffering on the part of the miners, of uncanny cruelty from the coal operators, of gross callousness on the part of governments. He reminded the starving people before him that Governor Conley was one of the state executives who had answered an inquiry about hunger from the United States Senate that there was no starvation in West Virginia and he urged the miners to hold their ground. “In the end we shall be fed or we shall go out and take food,” was Keeney’s parting words to his coal diggers. And the miners did hold their ground. All day long they remained at the Capitol. Newspaper reporters darted in and out of the demonstration. The townspeople came to see what all the shouting was about and more miners showed up from the camps. Long before nightfall they were the talk of the town. When it had started, no one thought the demonstration would last more than a few hours, but with a blank refusal of their demands, and their resolution to stay until fed, a dilemma presented itself. The miners had marched away from home expecting to return by nightfall. But when darkness came the demonstration was in full blast. Those who could remained; others went home to lock up the house and bring their families into Charleston.

This diminished the crowd and naturally enough the authorities then moved into action. Mayor DeVan appeared to persuade the committee to disband the crowd. The committee refused so to advise the mob but rather repeated the mayor’s request and recommended that they remain. Then the Mayor intervened and appealed to the hungry ones peacefully to go home because his own and the city’s sympathy was with them. But they hadn’t come for sympathy. They so told the Mayor and refused to budge. Then he ordered the state police to clear the streets, to escort the miners out of the north end of the city. This meant that they were to be driven a few blocks up stream and leave the streets of Charleston in the southern direction in peace. The State Police moved towards the demonstrators and at that moment Frank Keeney mounted the steps in the dark and called his men to hold the fort. They did—to a man. “I say,” shouted the Mayor, “they will march out of the North End of the city.” “And I say,” yelled Keeney, “they will march to the Southern part of the city.” Then he told the men that Splash Beach was open to them, that they could march there and encamp “until we get 10,000 miners in here.’ The police did not touch a man, the Mayor backed down, the crowd raised its banners and marched down Kanawha street to the southern end of town and camped. As the parade began the city clocks tolled the hour of midnight. Splash Beach is owned by a member of the State Legislature who offered the place to the miners for their demonstration.

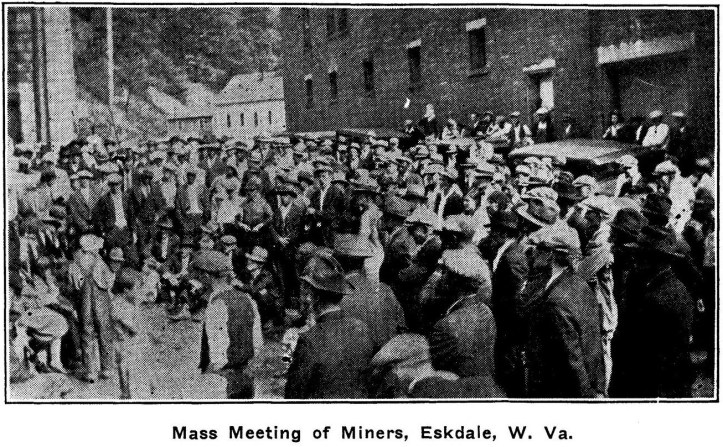

On Sunday, the following day, Splash Beach was full of hungry people. The place contained a water supply, toilets, and two small shelters used for bathers to change clothes. There was a place to swim and a lot of shady trees but that was all. Two miles up the river the Capitol rears its golden dome but the city of Charleston adjoins the beach and there the demonstration continued day after day. A thousand starving people were there coming from camps which lie back in the mountains from 20 to 80 miles. In the main they were Frank Keeney’s coal diggers but other unemployed men from Charleston proper and the valley added their numbers and their voices to the demonstration. Keeney was elected spokesman for the group. Brant Scott, vice-president of the West Virginia Mine Workers, was put on the committee to negotiate with the state. George Scherer, secretary of the union, remained in the camp. The group organized committees to manage its affairs, to solicit food in the city, to schedule mass meetings, to carry on in a situation for which there was no blue print, the end of which no one could foretell.

A Very Different Governor

Governor Conley was present on Monday when the committee returned to the Capitol. He was cordial and cooperative and a very different governor from what he was in the demonstration of last year. He had instructed his secretary to tell the miners to go home and beg food from other starving miners the day before, but he himself made no such proposition after the coal diggers had refused to disband and while their numbers were increasing. He remained in his office and kept the door constantly opened to the demonstrators. From his desk, machinery began to operate and county funds came to light that could be used for food. The Red Cross in one of the counties suddenly found that it had some supplies on its hands that unemployed men, not suffering exactly from an act of God, could eat. But there was still the eviction business. Up on Paint Creek the evicted families from Gallegher were still strewn on the water bank. Another conference with the governor and the Attorney General was held to look into that. Scott was there; also Seacrist who lives a mile from the evicted families. The committee had the facts and their souls were burning with indignation. And then for West Virginia a miracle happened.

The Attorney General said he would not only halt the scheduled evictions but he would see that the thrown-out families would be picked up and taken back into their former homes—owned by the coal company. The miracle appeared when on the following morning the state of West Virginia did send trucks up to Paint Creek and carry the evicted families and their furniture back into coal company property— the same houses from which they had been dumped a few days before the hunger march. Nothing like that has ever occurred before in West Virginia. The miners, and everybody else, were dumbfounded.

After the first conference with the state on Saturday night, nothing was said about driving the miners out of the town. The attorney general or the governor made no reference to the committees about “going home.” The city and state police hung round the camp but they said or did nothing. There was a camp police picked from the ranks of the hungry. Frank Keeney gave passes in and out of the beach. The attitude of the people of Charleston was obviously sympathetic to the miners. Business men and residents gave food to feed the camp every day; people brought blankets, coats and medicine over to the demonstrators. Women from the upper crust came to the camp in swanky automobiles, rubbed shoulders with much less fortunate women in rags there, only to drive their cars home to be loaded with supplies for the campers. In the City Council, quite unsolicited from the miners, a councilman introduced a resolution attacking the Mayor for attempting to drive the demonstrators off the Capitol grounds. Another resolution was similarly introduced asking that money be provided to feed the campers. These measures were tabled, but only after hours of debate, and at that they got six votes, and the news- Papers carried the full story the following day. But the greatest display of solidarity was in the camp itself.

Because of geographical barriers and coal operator control, it is almost impossible to assemble 1,000 miners in the Kanawha valley. The hunger demonstration brought them together and they met, many of them for the first time, since the famous “Armed March” of 1921. A lot of stories were passed around, a lot of new resolutions made. There were eighty men there from Logan County — a place where miners are locked up like prisoners and who never before felt the warm solidarity of men massed together in a common misery. A story told in a speech by a Negro from Logan in the camp cannot be recorded here, but it is burned into the blood of a thousand coal diggers; and the rest of us who heard it will be a long, long time forgetting. While the miners were encamped, they listened to union speeches, to men talking for the Independent Labor Party of West Virginia, they wrote and learned to sing new songs of labor; and their own instinctive solidarity grew as the eventful days passed.

All during the demonstration, the miners continued to win sympathizers to their cause. There was but one organized attack on them and that came from the United Mine Workers of America which only served further to disgrace that union in West Virginia. Officers of that organization caused a resolution to be presented to the governor and in the press attacking the demonstration, accusing Keeney and Scott of “stirring up trouble.” The resolution was signed by three local members of the union but engineered by a labor politician in the state house. The miners exposed the trick and condemned the politician. When the return of the evicted families took place, the same politician attempted to claim credit for that action to his union but this was too raw and was merely laughed away by the coal diggers.

On the evening of June 9, the demonstration was officially ended. Hundreds remained in camp until the following evening and on Saturday the demonstration which was then one week old was the main topic of conversation in the streets of Charleston. It had remained on page one of the local press every day and by and large it got a good break in the news. The reporters were obviously with the miners, and one editorial appeared in their behalf. There was no press condemnation.

Permanent Jobless Organization Formed

The success of the demonstration was unexpected. No one thought the miners could or would ‘stay in town for a week. No one thought the state would offer anyth{ng but promises. What did happen was because of the unknown element which lies hidden in every movement of organized action. And now that all of this did happen no one here believes that the unemployment problem has been solved; that there is no longer suffering and hunger in the coal camps. They all know better than that here. Foreseeing the same old conditions returning once the demonstrators had returned home, the hunger marchers set up committees to constitute a permanent organization to function in a collective manner with the starvation problem. A general committee will oversee separate county committees; these committees have already functioned in the demonstration and have heard all the pros and cons of relief agencies. They have met the personnel of the state and county authorities. They will act as a clearing house for all the different relief problems that otherwise get lost in the maze of red tape and evasive action of county and state agents. They will call the unemployed together in the separate counties; they will conduct demonstrations; and the general committee was authorized to reassemble the hunger marchers in Charleston again when necessary.

They won something and that they know, but they also suffered. There were no beds in camp. Every man, woman and child slept on the river bank under the trees and crude shelters they made themselves out of river grass. The nights were cold. Bonfires kept burning to warm numb bodies between naps. There were no dishes or cooking utensils except those improvised from tin cans. Many an old ex-mountaineer dug back into his memory and again whittled wooden dishes, forks and spoons from a distant past habit. He carried them home with him too to place beside the mementos of the “Armed March,” the “Bull Moose Death Train,” and other milestones that mark the history of his struggle for freedom. People got sick in the camp, of course, and in the end the strongest men among them were so changed from fatigue they appeared to have been through a war. But they stuck it out, they did not complain and they remained a solid mass until the end. They went home, as their own published statement said, “much wiser than when we came, realizing that not all of our trouble is over, but with a sure feeling that through organized action workers can get results—and we are resolved to stand by the West Virginia Mine Workers’ Union which led us in our hunger march.”

P.S. On June 13, the Monday following the demonstration, Kanawha County transferred forty thousand dollars from the county road fund to the poor relief fund to be used for unemployment relief. This action comes as a direct consequence of the hunger march and was one of the methods suggested by the committee from the hunger demonstration to Governor Conley whereby immediate relief could be provided. END.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v21n07-jul-1932-labor-age.pdf