It is the practical, not theoretical, that is the focus of this intervention from Kamenev’s in the debate on the meaning and the practice of Marx’s old adage after the Bolshevik Revolution, and particularly after Kautsky’s book. What was, in its totality, an incredibly rich discussion.

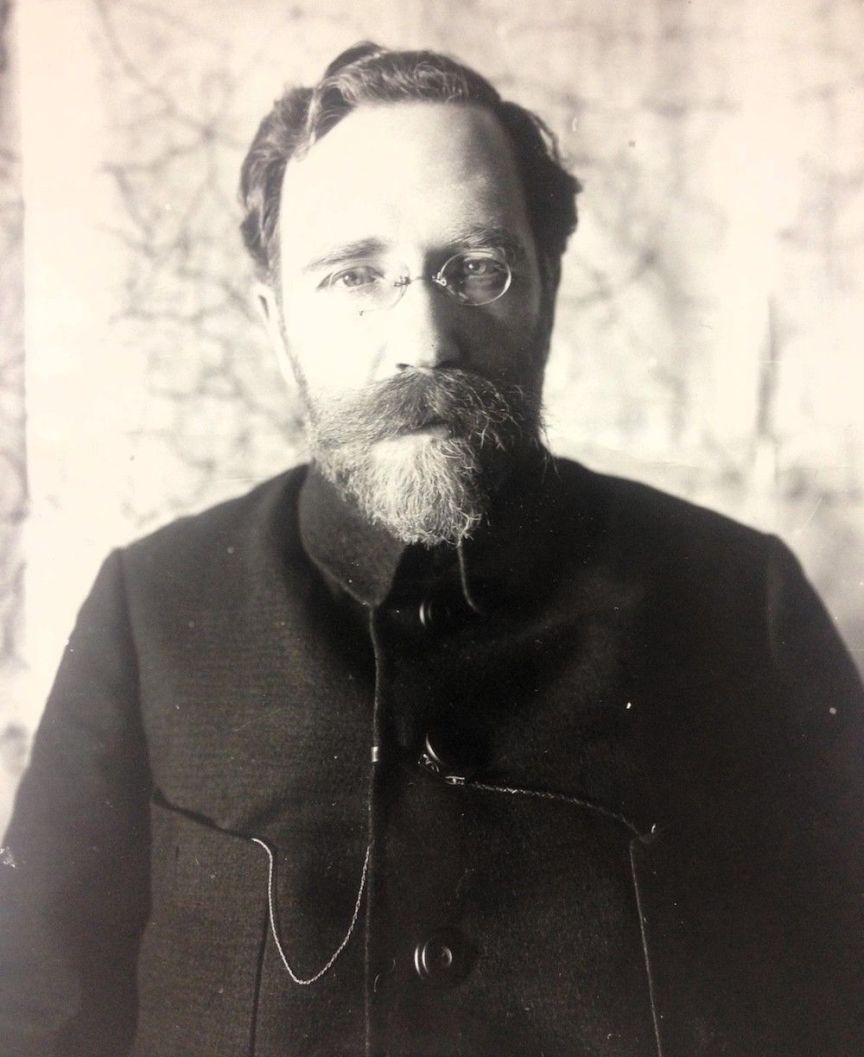

‘The Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ by Lev Kamenev from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 11-12. June-July, 1920.

The conservation of ideology, the theory of principles, the slowness of their adaptation to the rapidly onward coursing life, their constant looking behind the new recurring forms of the struggle—have frequently been noted by the Marxists. In our struggle for Communism we constantly meet with these facts, we constantly have to remark how great is the power of the old ideology even over the best men ot the present Labour movement—in so far as these men have grown up in the atmosphere of pre-war Europe.

This mental conservatism is most particularly observed in the question of dictatorship. Six years of war and revolution (1914-1920) it would seem, should have elucidated this finally, from all points of view by practice, by facts out of the everyday life of the masses, and yet, even among the comrades adhering to the Third International, it often occurs to us to hear the question: “What is the dictatorship of the proletariat?…Cannot the Labour movement attain its object without a dictatorship?…Why is dictatorship inevitable?” I have heard these questions not only from the members of the English Trade Union delegation, but even from some of the members of the delegation of Italian Socialists.

When one hears such questions, one thinks involuntarily that the persons uttering them must have slept through a whole historical period, and first of all they have slept through the world war of 1914-1918. These years have been samples of the epoch of dictatorship, and the methods of carrying on the war were models of the application of dictatorial methods of ruling a country.

From the point of view of the government of a country the imperialist war consisted in the assembling and placing under a single command of millions of men, in providing their equipment and transport, and in compelling these many-millioned masses to carry out certain tasks. These tasks were foreign to these millions of men and accompanied, for each of them separately, with unheard of sufferings, privations and the risk of death. How did the governments of Europe, America and Asia accomplish their task? By what methods did they guarantee the assembling, equipment, transport and command of these millions? By what methods did they attain that the whole administrative, economical and social life of state was adapted to carrying out of the tasks set by the government? Was this achieved by means of democracy? By the means of parliamentarism? By means of the realisation of the sovereignty of the “people”?

The sovereignty of the people, democracy, the state, parliamentarism, even from the point of view of their hypocritical bourgeois defenders cannot but mean the discussion and decision of the most important questions of the state and social life of the “free” citizens, although “sovereign” in the eyes of the law.

However, at present, even the most obscure unenlightened peasant of the most backward of all countries drawn into the war knows that the government of a country in 1914-1918 was in general and in particular a clear, simple, most elementary refutation of these regulations of bourgeois democracy. Democracy, parliaments, elections, freedom of the press remained—in so far as they did remain—a simple screen; in reality all the countries drawn into the war—the whole world—were governed by the methods of a dictatorship, which utilised, when it happened to be convenient and profitable, the elections, and the parliaments, and the press.

One must be a blind fool or a conscious deceiver of the masses, not to see or to conceal the fundamental fact at the most critical period of their history, at the moment of their struggle for existence the bourgeois States of Europe, Asia and America defended themselves not by means of democracy and parliamentarism, but by openly passing over to the methods of dictatorship.

It was the dictatorship of the general staffs of the officers’ corps and big industry, to whom belonged not only essentially but also formally all the power in the army and in the country, who commanded not only the lives, but also the property of the whole country and each citizen, not only living at the time, but yet to be born (the military debts of Messrs. Romanov, Hohenzollern, Clemenceau and Lloyd George will cover the lives and work of future generations).

During the course of several years, before the eyes of the whole human race, a picture of the practice of dictatorship is unrolled, a dictatorship ruling over the whole world determining everything, regulating everything and confirming its existence by 20,000,000 corpses on the fields of Europe and Asia. It is natural, therefore, that to the question, “What is dictatorship?” the Communists should answer: “Open your eyes and you will see before you a beautifully elaborated system of bourgeois dictatorship, which has achieved its object, because it has given such a concentration of power into the hands of a small group of world imperialists, which allowed them to conduct their war and attain their peace (of Versailles). Do not pretend that dictatorship, like a system of government, like a form of power can frighten any one except the old women of bourgeois pacifism. The dictatorship of the proletariat does not suppress ‘equality,’ ‘liberty’ and ‘democracy’; that is the function of the bourgeois dictatorship, which in 1914-1918 has shown itself to be the most bloody, most tyrannical, most pitiless, cynical and hypocritical of all forms of power that were ever practised.”

The theorists of Communism, beginning with Karl Marx, have proved, however, a long time ago, that the dictatorship of the proletariat does not consist in replacing the bourgeoisie by the proletariat at a given apparatus of government. The duty of the dictatorship of the proletariat is to break up the apparatus of government created by the bourgeoisie, and to replace it by a new one, created on a different basis and reposing on a new correlation of the classes.

The dictatorship of the proletariat appears in the programmes of Socialist Parties not earlier than the seventies of the nineteenth century. However, during the whole period of the Second International, it did not once become the practical duty of the day, and did not attract the attention either of the practicians or the theorists of the Labour movement; and only when in 19141918, through the veil of democracy, parliamentarism and political liberty the ambiguous features of the bourgeois dictatorship were clearly discernible, did the idea of a dictatorship of the proletariat become a real force. It became a force because, as Marx says, it took possession of the proletarian masses.

In the programme of the Russian Social Democratic Party in 1908, which aspired to be only a precise and improved wording of the programmes of the former Social Democratic Parties, and which at the time, in 1908, united both the Bolsheviki and the Mensheviki, the idea of a dictatorship of the proletariat was expressed as follows:

“The necessary condition for a social revolution is the dictatorship of the proletariat, that is, the proletariat must acquire a political power that will allow it to crush all resistance on the part of the exploiters.” This definition has entered fully into the programme of the Russian Communist Party.

The authors of the programme of 1903 could not foresee the real circumstances in which the proletariat of some country would have to seize the power into its hands. They certainly did not attempt at the time to define in what measure the dictatorship of the proletariat would be connected with the formation of the proletarian (Red) army, with the practice of Terror, with the limitation of political liberty. They had to underline and they did underline, not these changeable elements—varying in the: various countries—of the proletarian dictatorship, but its fundamental feature, unchangeable and obligatory for any country and any historical conditions under which the proletariat seizes the power.

The proletariat not only seizes the power; in grasping it, the proletariat gives to it such a character, such a degree of concentration, energy, determination, unlimitedness, which, according to the words of the programme, “will allow it to crush all resistance of the exploiters,” that is the fundamental feature of the dictatorship of the proletariat.

The dictatorship of the proletariat is thus such an organisation of the state and such a form of government of state affairs, which in the transitional stage from capitalism to Communism will allow the proletariat, as the ruling class, to crush all resistance by the exploiters to the business of Socialist reconstruction.

It is thus clear that the question itself of the necessity, the inevitability of a proletarian dictatorship for a capitalist country is connected with the question as to whether the resistance of the exploiters against their expropriation by Socialist society, or, more precisely, by society marching toward Socialism, is inevitable.

In the same way is the question regarding the degree of severity of the dictatorship, of the proportions and conditions of the limitation of the political rights of the bourgeoisie or of the limitation of political liberty in general, of the application of terroristic methods, and so on, is indissolubly linked with the question of the degree, forms, stubbornness and organisation of the exploiters.

Any one who expresses a doubt as to the inevitability of a dictatorship of the proletariat, as a necessary stage towards a Socialist society at the same time expresses a doubt of the bourgeoisie showing any resistance against the proletariat at the decisive hour of the expropriation of the exploiters.

The propaganda based on this may be dictated either by individual stupidity or the interestedness of a group of persons to conceal from the proletariat the circumstances of the forthcoming struggle and to prevent it from preparing for the same.

When persons, calling themselves Socialists, declare that the course of dictatorship, admissible and explainable for Russia, is in no wise obligatory or inevitable for any other capitalist country, then they proclaim something directly contrary to truth. It is true, the Russian bourgeoisie always was and up to the October Revolution remained the least organised, the least conscient in the sense of class, the least united of the bourgeoisies in the countries of the old capitalist culture. The Russian peasantry had not time to put forward a group of strong and politically united peasantry, which is the basis of a series of bourgeois parties in the West. The Russian small bourgeois of the towns, crushed and politically-unenlightened, never represented anything like such groups of the population, which in the West form and support the parties of “Christian Socialism” and anti-Semitism.

The first thunder claps of the proletarian revolution broke over this politically backward, inactive and unorganised class. “The resistance of the exploiters” against the blows of the Russian proletariat must therefore be considered as comparatively weak, naturally, weak only in comparison with the activity which the bourgeoisie of any European country will be able to develop. The actively resisting element, which extended the struggle for three years, were not the unorganised forces of the Russian bourgeoisie but first of all foreign interventionists, and after them the bourgeoisie of the frontier countries (Finland, Lithuania, Poland, Ukraina), which managed to unite under the flag of nationalism and by playing upon the century-old hatred against the Tsarist Russia certain organised groups for the resistance against the Russian proletariat. If it were not for these external circumstances the resistance of the Russian bourgeoisie would haye been broken not in three years, but in three months and the proletarian apparatus of state power would naturally have directed all its energy towards other matters.

In conformity with the nature of the resistance which was to be expected from the Russian rich classes and their organisations the dictatorship of the proletariat in Russia had its period of “rosy illusions” and “sentimental youth.”

There can be nothing more mistaken than to presume, that the Russian proletariat, or even its leader, the Communist Party, had come into power with recipes prepared in advance of practical measures for the realisation of the dictatorship. Only “Socialist” ignoramuses or charlatans could affirm that the Russian Communists came into power with a prepared plan for a permanent army, extraordinary commissions, and limitations of political liberty, to which the Russian proletariat was obliged to recur for self-defense after its bitter experience the cause of the proletariat was saved, because it soon profited by the acquired experience and with unfailing energy applied these methods of struggle when it became convinced of their inevitableness.

The transfer of power of the Soviets and the formation of the new workmen-peasant government took part November 7th, 1917. The discomfiture and unorganisation of the bourgeoisie were so great that it did not move out any serious forces against the workmen. The resistance of the government of Kerensky was broken after a few days. The elections to the Constituent Assembly still continued. All the political parties—up to Miliukov’s party—continued to exist openly. All the bourgeois newspapers continued to circulate. Capital punishment was abolished. The army was being demobilised. In the hands of the government there were no other forces than the volunteer detachments of armed workmen. The Ministers of Kérensky’s government, arrested during the first days, leaders of the Social Revolutionist Party, Avksentiev, Gotz, Zenzinov, Generals Boldarev, Krassnov and others—later on all of thein leaders of the armed struggle against the Soviet power and members of the mutinous governments of Siberia, the Don, and the South—are set free. Generals Denikin, Markov, Erdeli and others remain in the hands of the Soviet power up to November 20th ani leave its limits alive.

Yes, that was the period of “rosy illusions.” It continued for a few months.

The conditions began to change by April-May, 1918. In April, 1919, the decree regarding the formation of a permanent Red Army was published. Only in April the extraordinary commissions acquired the right to apply capital punishment by shooting at robbers caught in the act and to officers going off to Kornilov, according to his secret mobilisation. Only June 18th the Revolutionary Court passed its first sentence of death against the Admiral commanding the Baltic Fleet. Only in May measures were taken to stop the publication of the bourgeois papers (at the moment of this disclosure there were thirty bourgeois papers against three of the Soviets in Moscow alone). Only in June, 1918, were the Mensheviki driven out of the Soviets.

Thus over six months (November, 1917, April-May. 1918,) passed from the moment of the formation of the Soviet power till the proletariat practically applied any harsh dictatorial measures. This increased severity in the dictatorial régime was called forth by a series of very elementary facts: In April the Government of Skoropadsky was organised in Kiev, in May took place the uprising of the Tchecko-Slovaks, their seizure of the railway system and the formation of the Social Revolutionist government in the East; in May, too, the Cossack counter revolution on the Don—the Russian Vendée—acquires increased proportions under the command of General Krassnov.

In conformance with this all the attention and energy of the labour class are concentrated on the tasks of the war and the Soviet State is transformed into a camp of armed proletarians.

Such is the experience of the Russian proletariat. We have now before us the experience of the class struggle for the proletarian power in Finland, Hungary and Germany. The fundamental difference between the experience of Hungary, Finland and Germany and that of Russia consist therein that the bourgeoisie of those countries, proved, as was to be expected, to be much more organised, united and capable of fighting than the Russian bourgeoisie. Its period of disconcertion was much shorter; it organised a counter attack against the proletariat much more rapidly and energetically and shortened thus the period of illusions of the proletariat itself regarding the nature of its dictatorship.

The experience of the proletariats of Russia, Finland, Hungary and Germany allows us to establish an empiric law on the development of the dictatorship of the proletariat; it may be expressed approximately in the following words: The fact of the acquisition of the central political power by the proletariat does in no wise complete the struggle for the power, but only serves as the beginning of a new and more obdurate period of warfare between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat.

After the first blow of the proletarian revolution and the seizure of the central apparatus of the power by the proletariat, the bourgeoisie invariably needs a certain time for mobilisation of its forces, the drawing wp of reserves and their organisation. Its passage to a counterattack opens an epoch of undisguised warfare, and armed confrontation of the forces of both sides.

During this period the ruling power of the proletariat acquires the harsh features of a dictatorship: the Red Army, a terroristic suppression of the exploiters and their allies, the limitation of political liberty become inevitable if only the proletariat does not wish to give wp the acquired power without a fight for it.

The dictatorship of the proletariat is consequently a form of governing the state which is the most adapted to carrying on a war with the bourgeoisie and to guarantee the most rapidly the victory of the proletariat in such war.

Are there any grounds for presuming that such a war in Europe will be carried on in less acute forms? That the European bourgeoisie will submit with a lighter heart to the expropriation of its riches by the proletariat? Can any reasonable person build his tactics on the supposition that the European bourgeoisie will not show all the resistance that it is capable of against the proletariat. in power? Can one presume that on entering into the fight against the proletariat in power, the European bourgeoisie will prove to be less armed, less capable of fighting, less united and prudent than the bourgeoisies of Russia, Finland or Hungary? Can one think that it will stop at any means, beginning from the long-existing union with the betrayers of Socialism from the camp of the Second International up to the bombardment of the workmen’s quarters and the application of first rate technical methods for the destruction of the enemy in war?

What under these conditions can a doubt in the inevitableness of the methods of a proletarian dictatorship mean but a refusal to work daily for the preparation of the proletariat to utilise all the methods of dictatorship in the coming struggle?

To proceed towards a seizure of the power, not hoping and not preparing the conditions to hold it, is simply adventurousness; to recognise the necessity for the proletariat to acquire the power and to doubt the necessity of a dictatorship of the proletariat, to refuse to instruct the workmen in this direction—means to consciously prepare the betrayal of the cause of Socialism. Any one who does not recognise the necessity of the severest proletarian dictatorship during the transitional period from capitalism to Socialism; who does not prepare the conditions therefore, so that the proletariat, on acquiring the central apparatus of the power, should direct it to the suppression of the resistance of the exploiters; who does not ex plain to the proletariat at once, a8 a necessary condition of its victory, the inevitableness of an armed struggle and harsh measures against treason and fluctuations and does not arm the proletariat with the corresponding means, such a person is preparing the ruin of the proletariat and the victory of the bourgeoisie.

But if the dictatorship of the proletariat is such an organisation of the power, which is the most adapted to the carrying on of the war against the bourgeoisie and the suppression of its resistance, then we have an answer also to the question which is generally set to the Communists by the different syndicalists. The latter, which admitting the dictatorship of the proletariat, cannot desist from their old prejudices against the political party of the proletariat. The question, consequently, consists therein, what organisation is capable of realising the tasks of the dictatorship?

There can be no doubt that in the moment of the decisive class war the power of command and compulsion must lie in the hands of a definite organisation capable of bearing the responsibility for each step and of guaranteeing the consecutiveness of these steps.

The army of the proletariat moving in battle order must have its general staff. When leading its regiments to the attack his general staff must be capable of surveying the whole combination of the international, political and economic conditions of the struggle. It must possess equal authority over all kinds of arms, which are at the disposition of the working class. It must be in a position to carry out its revolutions through the Labour Unions, and the workmen’s cooperations, through the factory committees, and through the unions of young workmen, by means of written propaganda, and through the fighting militia of armed workmen.

At the moment when the old power is overthrown and the apparatus of government is seized by the revolted proletariat signifies the disorganisation of the old social life. The formation of a new army, the guaranteeing of provisions, the building up of the industry on new principles, the organisation of law courts, the establishment of relations with the peasants, the diplomatic relations with other countries—all these matters become at once the nearest tasks of the general staff of the victorious army of the proletariat. Any delay in the solution of one of these tasks or any hesitation in the decision is capable of bringing the greatest harm to the further victorious development of the proletarian revolution.

Consequently, this general staff must be an organised, responsible and centralised institution prepared to deal with and decide all political, economical, social and diplomatic problems. An organisation which would satisfy these condition and accomplish the tasks laid upon if may certainly be called by any name whatever, but as a matter of fact, such an organisation can only be the political part of the proletariat; i.e., an organisation of the most advanced revolutionary elements of the proletariat, united by their common political programme and an iron discipline.

Such an organisation cannot be formed within a day or even a week; it is the result of a lasting selection and assembling of their leaders, who have proved by their daily work to be capable of estimating rightly each form of the labour struggle and the interests of each separate group of the working class from the higher point of view of the general interests of the entire working class as a whole.

The greatest misfortune which could befall the proletarian army, Seizing the strongholds of capitalism, would be if the apparatus of leadership would prove to be in the hands of men, or groups or organisations whose preceding work had been carried on only in the sphere of the labour movement.

The suppression of the resistance of the exploiters—which is the fundamental task of the dictatorship—is not only a military, or only a political, or only an economical task, it is all of them, military, political and economical. The resistance of the exploiters requires its most acute form during the armed strife; but the rich peasantry, which does not give the bread for the famishing population; the engineers, refusing to work for the industry, and the bankers bringing confusion into the mutual accounts of the industrial enterprises by concealing their books—are not less important factors in the resistance of the bourgeoisie. The suppression of all these various forms of resistance can no less be the work of an organization formed in the narrow sphere of the industrial labour movement, as, say, an organisation in the sphere of a labour corporation. It can be successfully achieved only by a general organisation of all the workers, in the form of their Soviets, in which are represented all the forms of the labour movement and which are under the guidance of a political party concentrating in itself the whole experience of the preceding struggle of the working class.

In the epoch of the dictatorship of the proletariat the Communist Party is more necessary to the working class than in any other. It is the necessary condition for the victory. A refusal to work for its creation and strengthening means renunciation from the efficient leading of the class war; i.e., a renunciation from dictatorship, from a condition of the victory of Socialism and may engender, although even unconsciously, the most cruel betrayal of the labour cause. by depriving the proletariat at the most grave moment of its most important arm. Any one who doubts of the inevitableness of the dictatorship of the proletariat, as a necessary stage towards its victory over the bourgeoisie, facilitates the conditions of the latter’s victory; any one who doubts or renounces the political party of the proletariat, is preparing the weakening and disorganisation of the working masses.

June, 1920.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n11-n12-1920-CI-grn-goog-r3.pdf