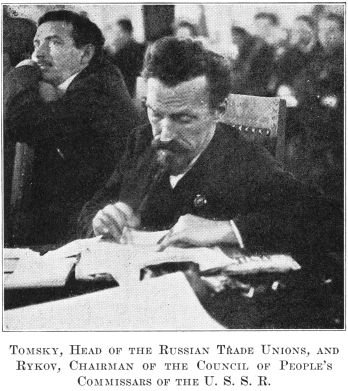

A major speech by Rykov detailing the state of the soviet economy to the Sixth Trade Union Congress of the U.S.S.R as the debate over the future of the N.E.P. begins in earnest.

‘The Economic Situation in the Soviet Union’ by Alexei Rykov from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 4 No. 85. December 16, 1924.

The Economic Situation in the Country.

In order to gain an accurate idea of the present economic situation in the Soviet Union, with its population of 130 million inhabitants, we must first of all describe the economic position of the majority of the population of our Union, that is, of the 100 million human beings comprising the peasantry.

This is necessary for the reason that these 100 millions human beings out in the country represent the basis of the whole of the economic life of our republic, the foundation upon which our industry and the working class have worked and are still working. Industry receives a considerable part of its raw materials from the peasantry, and industry provides the peasantry with its products. The further growth of our industry, especially of our lesser industries, depends upon the quantities of our goods purchased by the peasantry, for the most important market, the only market based upon the masses and possessing unlimited possibilities, for the workers and for the factories, is the village.

The Area under Cultivation.

During the last two years the area cultivated has been increased by almost 30%. Its extent is already 88% of the pre-war area.

It must be observed that the extension of the area cultivated is not proceeding regularly over the whole area of the Union. In some districts the area cultivated is greater than before the war. The consuming regions are to be classified under this category. Here the area under cultivation already exceeds that of the year 1916 (the 1916 area being approximately to that before the war). In the consuming areas the area cultivated has increased as follows, compared to the standard of the year 1920: in the year 1921 by 13%, in 1922 by 28%, in 1923 by 35%, and in the year 1924 by 47. The area under cultivation in that part of our producing districts which did not suffer from the failure of crops in 1921 has increased in the same, or a slightly lesser degree.

This goes to show that if we had not encountered the elementary catastrophe of the famine in 1921, our industry would now, at the beginning of the economic year 1924/25. have almost reached the pre-war level: The whole productive region in the South West and on the Volga, which suffered severely from the famine in 1921, has remained behind the other regions in the restoration of its cultivated area.

The present year is a year of bad crops. This year the peasantry have brought in 9 to 10% less grain than last year. But we can already make a calculation of the results of the winter corn for the year 1923. This calculation shows an increase of winter sown area, the average for the whole Union being 5% in the districts where the crops have failed, and even 10% in the districts suffering from this year’s failure. This is a result of the policy pursued by our government of its struggle against the failure of crops, a most important factor of which is the maintenance of the economic significance of this region, furthered by grants of seed, by public works, etc. Thanks to these aids, it has been possible for the area sown in these regions to be not only maintained at the level of the year before the failure of crops, but to be increased by 10%.

Changes in Kinds of Crops.

The increase of the area cultivated is accompanied by a considerable change in the nature of the crops grown. The so called consumers’ crops of corn, millet, etc. play a part of ever decreasing importance. A larger proportion of the more valuable descriptions of grain is being grown. Thus for instance the area under cultivation for wheat, as compared with that for rye, has increased from 15% in 1922 to 20% in 1924.

On the other hand, the cultivation of technical plants is gaining steadily in importance. These are naturally consumed entirely or chiefly by industry.

A few figures will give an idea of this: Area cultivated (in thousand desjatines)

1922: 52—818–169

1923: 165–844–266

1924: 419—1056–320

1924 as compared with 1922: 804%–130%–189%

Cattle Rearing.

With respect to the rearing of live stock, there is still a very great shortage of horses, the most important agricultural draught animals. The total number of horses does not exceed half of the number existing before the war. The number of farms working without horses reaches the figure of 40% in many places, especially in districts where the crops have failed. At the present time it is the first task of our agriculturalists to increase the number of horses, and to decrease the number of farms working without them. During the last two years the number of our horses has only increased by 10%. On the other hand, our stock of large cattle has increased by 32% since 1922, that is, it has increased by one third. The number of sheep has reached pre-war level. Other branches of animal rearing (pigs etc.) are able to record an increase of 300% in comparison with 1922. Cattle rearing is beginning to play a role of ever increasing importance in the budget of the farmer, and a great part of the agricultural single tax” is today not being paid from the proceeds of corn growing, but from the proceeds gained by the products of cattle rearing or by the sale of cattle, especially of the smaller animals.

The Significance of the Revival in Agriculture.

This is the present situation of our agriculture, which can be summed up by the statement that despite the famine year of 1921 great advances have been made during the last few years, the upward tendency being well maintained in spite of this year’s bad crops, which are a slight set back, but by no means interrupt the favourable development. The importance of this revival in agriculture, and of the resultant enhanced purchasing powers of the peasantry, is extraordinarily great. The following gives an idea how great: Last year we were plunged into a crisis for lack of markets; our industry languished, and could find no purchasers. In the course of this one year the revival in agriculture has so changed the markets that there is a shortage of goods. Industry cannot supply the amount of goods required to meet the requirements of the peasantry and agriculture.

Improved conditions in agriculture have been the basis for the restoration of our industry, for the recovery of our budget, and for the progress made in every branch of our economic life. They have proved the chief prerequisite for the development of the cities, for the development of industry, and for the development of the working class.

But this revival in agriculture does not by any means entitle us to jump to the conclusion that the peasantry now wants for nothing, that there is no more poverty in the villages, and that the peasantry have no longer to suffer want and privation. In many districts the peasants are still living in the direst need, but during the last few years we have made rapid strides towards a permanent and comparatively rapid uplift in agriculture and towards an improvement in the situation of the peasantry.

The Growth of our Industry.

The increased prosperity of the peasantry has enabled our industry to develop, especially those branches of industry which provide for the needs of the peasant and the farm, that is, light industry. The recovery of light industry has been followed by that of heavy industry. When we passed from war communism to the new economic policy, our total industrial production did not amount to more than 18 to 20% of pre-war production. In the course of the last few years industrial production has increased by about 30 to 40%, and reached 50% at the beginning of the present economic year. If we take into consideration that at the time of transition to the new economic policy we have only attained 20% of pre-war production, and have now risen to 50%, this is a very great advance; but in spite of this very rapid progress we are not yet producing more than half as much as was produced before the war. Up to very recently the progress which we were able to record for our industry has referred chiefly to our light industry.

We are not able to record a certain degree of progress for our heavy industry. We have been especially successful in the production of mineral fuels. Thus we have been able to increase our output of petroleum, amounting to 233 million poods in 1920/21, to 360 million poods, or 55% of pre-war production, in 1923/24.

Coal.

In 1921 our coal output did not amount to more than 27% of pre-war production, and we passed from one fuel crisis into another. Last year our coal production reached 53% of pre-war production. But here our coal industry advanced too rapidly. It is almost the only branch of industry which has increased its production to such an extent that it cannot find markets at the present time. It has advanced too rapidly in comparison with other branches of industry, and must now slow down for the time being. Some 10 millions poods of coal are lying in the Donetz basin, dead capital, unable to find a market. The growth of fuel production must be brought more into line with the development of its chief consumer, the other branches of industry.

Naphtha.

Our naphtha production is in a different position, and has much scope for increased development. Our naphtha works are working to a great extent for the foreign market. Last year our naphtha export reached 85% of pre-war export. The circumstance that the balance of our naphtha industry is now covered to a considerable extent by export is not only of very great importance from the economic standpoint, but our naphtha export represents, so to speak, an international victory of Russian industry.

Metal.

The position is not so favourable in the metal industry. The recuperation of basic capital, the equipment of our factories, the restoration of agricultural stock and implements, all depend on the development of the metal industry. The development of the metal industry is the standard by which we can judge the degree in which the industrial frame work of our whole economics, industrial and agricultural alike, have been restored. The metal industry is far behind the other branches of industry in its development, and the same must be said of ore mining, which borders on the metal industry and is dependent on it for its development.

In the year 1921/22 the amount of cast iron manufactured did not exceed 10 million poods. I am not in a position to state exactly what percentage of pre-war production this is, but in no case is it more than 5%. By 1923 our cast iron production had increased to 40 million poods, that is, it had increased fourfold in two years. Our output of Martin steel increased from 36 million poods in 1922/23 to 60 million poods in 1923/24. This means an increase of 66% in the course of a single year. The same development is shown by our rolled iron output.

With regard to this year’s prospects, an increase in cast iron production from 40 to 50 million poods is provided for. As compared with the pre-war output, this is still but little more than 20%.

With regard to Martin steel, the production for next year is expected to be 81 million poods, that is, 38% more than in this year. As compared with pre-war years this is about 30 to 33%. Our output of rolled iron will be 35% of the pre-war production. This is the situation in the metal industry.

Difficulties in the Restoration of Heavy Industry.

The chief stumbling block in the way of the restoration of our heavy industry lies in the fact that it is impossible to restore it with the aid of the open markets only. Our industry was developed, during the old regime, by the aid of gigantic state orders railways, bridges, etc. The production of current goods for the market was a very secondary matter for most of our great metal manufactories.

Our budget at the present time places no means at our disposal for setting about any kind of work in the least comparing with the construction of the old Siberian railway. Thus the recovery of our industry depends much more than formerly from the agricultural market. At the present time agriculture is requiring agricultural machinery and implements to a degree utterly unknown hitherto. Additional working capital and reequipment of our factories are of equally urgent necessity for our industry. The speed at which working capital recovers in industry and agriculture, upon which the speed of development of the metal industry depends to a very considerable extent, is contingent on the extent of the accumulation taking extent is contingent on the extent of the accumulation taking the form of net profit in our industry or of taxes in our budget. We have no other means and ways at our disposal for the restoration of basic capital.

Manufacturing Industry.

The manufacturing (light) industry working for the great market of consumers, being able to make a rapid turnover, is able to recover much more quickly. I need not touch upon every branch of light industry. It is only necessary to refer to the cotton industry, as this plays the leading part. In the economic year 1923/24 the production of the cotton industry Increased sixfold as compared with 1920. A further extension, of about 60%, is expected for the economic year 1924/25. The output of cotton goods is already 60% of pre-war production. Should we have sufficient raw material, we shall have reached pre-war level in this branch of industry within the next two or three years.

Goods Traffic and Export.

The revival of industry and of its basis, agriculture, determines the whole of the other factors of our economics, thus the development of goods traffic, increased railway travelling, the development of our commercial system, and of private trade as a part of this system.

The growth of agriculture and industry as further led to the development of our foreign trade. If we take our foreign trade returns in the economic year 1922/23 at 100, then our comparative returns for the economic year 1923/24 have already reached the figure of 214, or more than double. The grain which we exported last year, to the amount of 200 million poods, played a considerable part in increasing export. According to preliminary estimate, for the economic year 1924/25 our total ex ports will exceed those of last year, although grain will be lacking among the articles exported. We fully realise that we shall not be able to export grain, and shall not export any. The gap thus produced in our export will be filled by an extensive increase in the export of naphtha, manganese ores, and wood.

Price Policy.

The main questions which we had to solve last year, in order to secure the possibility of uninterrupted progressive development for our economics, were in my opinion the two following: in the first place the tasks imposed by our price policy, and in the second place the question of stable currency. It is known to you that we replied to the crisis caused by lack of markets by reducing the prices, by a policy making it possible for industry to sell to the peasantry. For it was perfectly clear to us that unless a reduction of prices took place the peasantry could not buy. Thanks to our policy the following results were obtained: in the autumn of 1923, when the crisis was at its highest point, and we had a superfluity of goods and a shortage of purchasers, the angle of the scissors” (disparity between prices of agricultural and industrial products) was 3. 10. This means that industrial products were three times as dear as agricultural, compared by pre-war standards. The result was a state of affairs which may be designated as a boycott of industry on the part of the peasantry. In the sphere of politics this might have led to a breach of the alliance between the peasantry and the working class.

The policy of price reduction had the effects of closing the blade of the scissors” to an angle of 1. 46, so that at the present time the price of industrial products is no longer three times as high as that of industrial products, but one and a half times. You see that a very considerable success has been attained. The demand for industrial goods has greatly increased, and the crisis is reversed into a goods famine. Industry is no longer able to supply the wants of the peasantry. Thanks to our price policy, we have secured the absolute necessity of increasing production in the coming year.

The Stable Currency.

This success would not have been permanent, however, if we had not been able to combine it with another mighty achievement: the introduction of a stable currency. The commercial intercourse consequent on the new economic policy is carried on in the terms of money traffic.

Without a stable currency there is no trustworthy way of carrying out the exchange of goods between factory and village; where the currency is constantly depreciating, we are plunged into such an abyss of insecurity that all traffic in goods is not only thrown into disorder, but frequently made entirely impossible. The introduction of a stable currency has enabled us to bring about firmly established connections; by way of exchange of goods, between town and country, factory and agriculture. This colossal reform, representing one of the most important prerequisites for the restoration of our whole economics, has been accomplished and consolidated within a very brief space of time.

At one time the danger existed that our budge world require expenditure for which we had no revenues or sources of income, so that we should have to resort to a fresh issue of paper money. But in the current year we have succeeded for the first time, in balancing our finances without the aid of paper money.

The Budget and the Growth of our Economics.

Our budget cannot be called good, for it does not meet the needs of the Union, not even the most urgent needs. It does not satisfy the requirements of the broad masses of the population, whether in regard to the extension of our network of schools, or of our network of cultural institutions. Thus it cannot by any means be regarded as an ideal budget. We can only be content with it if we regard it as a starting point for the more rapid reconstruction of our economics. We can manage with such a budget for a year, or at longest two years, but it is needless to say that it is impossible to go on for any length of time without satisfying very essential needs.

We must however accept this year’s budget as it is, for it is the only possible budget, enabling us to guarantee the stability of our whole money system and currency, making it possible for our economics to make further favorable progress and permitting us to enlarge our next year’s budget rapidly on the basis of this progress.

We are Paying Fewer Taxes than Formerly.

In the Soviet Union the burden of taxation has not increased; it has lessened. The calculations made by the People’s Commissariat for Finance show that when we add together the whole of the direct and indirect taxes intended to be raised this year, the sum per head of the population will be seven roubles. Before the war the taxation per head of the population was eleven roubles. At the same time the purchasing power of our present gold rouble is less than that of the pre-war rouble.

With reference to agricultural taxation, we may say that for the current year this amounts to about 4% of the proceeds of agriculture.

The weak offers in grain are not to be explained by the assumption that the peasantry are not paying taxes (they are paying, but not from the proceeds of the sale of corn; other sources of income are employed), but by the fact that the peasantry is in a position to retain their corn. This means that the burden of taxation is comparatively light. We were of the opinion that the taxation was severe enough to throw large quantities of grain upon the market, but we were mistaken. In a large number of districts, for instance in North Caucasia and a part of the Ukraine, the peasants have paid the agricultural taxes from the proceeds of the sale of cattle rearing products (milk, cream, butter, etc.) and of the sale of melons. In North Caucasia further by the sale of sunflower seeds, etc. The second source of income enabling the farmers to pay their taxes is the rearing of smaller animals, a branch of agricultural activity now being carried on in some places even more intensely than before the war. This is the cause of the considerable fall in the price of meat. The peasant is however very cautious about selling his corn, although the grain prices are three times as high as last year.

The High Grain Prices.

Last year the chief factors of our political economy were the “scissors”, the price policy, the stable currency, and the budget. Apart from a few partial failures, we have been successful in solving these questions in all essentials, or have at least advanced far towards their solution. Today our difficulties consist of the high grain prices, the shortage of circulating media, and in the goods famine.

Last year in September rye cost 27 copeks loco farm. This year in September it cost 62 copeks. Wheat cost 53 copeks, today 96 copeks. This is the most important economic factor of the moment. It includes the most important essentials of our economics and our policy: the question of the alliance between workers and peasantry, and the question of the relations between the peasantry and the Soviet power. The question of the grain prices expresses the whole complexity of the politics required from us in an agrarian country.

This year’s grain yield is 9 to 10% less than last year’s. But the whole of the statistical returns go to show that our grain will suffice for the whole population of the Union, without the least shortage. We have worked out a plan for the purchase of corn for the requirements of the cities, of the working class, the army, etc. Our various organisations were to have purchased 170 million poods by the 1. October. We have only purchased 117 poods, that is, 53 million poods less. Our program formerly included the export of grain, but this year this is completely excluded. The purchase price has reached 1.20 roubles in some places. The party and the working class are confronted by the question of what policy they intend to pursue in view of the high and steadily rising grain prices. We have replied to this question by fixing the highest permissible prices for state purchase, these being 57 copeks for rye, 84.4 copeks for wheat. (Average figure for the whole Soviet Union.) The Question must be Settled by an Agreement Between the

Working Class and the Peasantry.

The price of grain represents a problem which in a certain sense demands an agreement between the working class and the peasantry. It need not be said that the workers are anxious for cheap bread, whilst the farmers prefer it to be dear. Under present conditions in Soviet Russia it is absolutely imperative, not merely desirable, that the working class and the peasantry co-operate. It is necessary to find a solution satisfactory to both parties. We cannot accept the offer made by the peasantry, that is, we cannot pay more than a rouble for their rye in the year 1924. Why? Because the price of corn determines to a great extent the wage of the workers. And the wage of the workers again determines the price of industrial products in a considerable degree. The price of corn must be taken into consideration when our budget is drawn up. An unlimited increase in the price of corn would overturn our budget, for it would involve a rise in wages, a rise in the price of goods, and the breakdown of our whole price policy and our struggle against the “scissors”.

The maximum grain price decided upon by us for this year is very high in comparison with last year’s price, but it is one which does not frustrate either our planning economics nor our price and wages policy, and it enables us to continue our policy of price reduction in our industry, although our maximum prices are lower than those originating spontaneously in the market. At the present time the question of maximum prices is being discussed everywhere among the peasantry, and it need not be emphasised that the members of trade unions will not be able to avoid very detailed debates on this subject under the present circumstances. Every worker must be ready with his reply to the question of why grain prices cannot be permitted to rise unlimited and spontaneously: the reply is that this is not to the advantage of the peasantry in the long run.

The Methods of Fighting the High Grain Prices.

The chief methods to be employed against excessive grain prices are: increase of cultivated area, increased production of grain, the intensification and revival of agriculture. The fixing of maximum prices must be regarded solely as a temporary measure for this year. The increased production of grain is the chief measure enabling us to prevent repetition of this year’s experience with regard to grain prices. Despite the high price of grain, we have contributed not inconsiderable quantities of seed corn in aid of agriculture, as these supplies of seed enable the area under cultivation to be extended, and the grain yield increased.

The Shortage of Goods.

The second question occupying our politcal economists is the shortage of goods. Lenin once said that the working class must show the peasantry that they are as well off under the dictatorship of the working class as under the dictatorship of the landowners and noblemen, that the nationalised industry can satisfy their wants as satisfactorily as a capitalist system. Today we are suffering from a shortage of goods felt most acutely by the peasantry a shortage of goods which prevents us from satisfying the most elementary needs of the peasantry The sole possibility of relieving this shortage of goods consists in increased industrial production. As already mentioned in the report on the textile industry, this has already been taken in hand. I fear, however, that this increased production may prove inadequate, as the extension of our industry does not depend solely on the requirements of the market, but at the same time on the extent of the means at the disposal of industry, and the means which we can give as credits. At the present time these means are still insignificant.

Our Trade Policy.

The circulating means at the disposal of industry are still very insufficient every member of a trade union realises this at once from the fact that his wages are frequently paid unpunctually. The demand for unlimited credit for the co-operatives would not only hamper the increase of industrial production, but would result in further irregularities in the payment of wages, etc. Should we grant such credits or not? I am not of the opinion that we should. The difference between wholesale and retail prices is still extraordinarily great, especially among the private tradesmen. Were industry to grant unlimited goods credit to the co-operatives, and especially such credit as would not always be punctually redeemed, then industry would be deprived of considerable resources which could be employed for trade, and the extension of production would be hindered.

Co-operatives and Private Trade.

The granting of unlimited credits to the co-operatives, and the suppression of private trade, have frequently been carried out wrongly in actual practice. The consequence is that we may presently experience a crisis among the subordinate co-organisations, in which the resources of industry often lie unutilised for long periods. We must exert our utmost endeavours to defeat the private tradesman, but with economic and not administrative means. Such detrimental factors as the purely administrative pressure put upon the private tradesman must cease; the unlimited credits granted to the co-operatives at the expense of industry must be revised; at times we must utilise private capital, when it proposes to furnish means advantageous to the development of trade.

In our present situation we suffer from a shortage of means enabling us to develop our factories and increase our circulating capital, and we cannot yet entirely dispense with the services of private capital for trading purposes, where this is of advantage to industry.

We shall of course continue to do our utmost, to the farthest extent of the powers possessed by the Party, the government, and our finances, to develop the co-operatives, but in such manner that our factories and industries are not damaged by it.

The Question of the Productivity of Labour.

The question of the productivity of labour is closely bound up with the collective organisation of our industry, and with the organisation of a new form of society. The chief task set us during the transition stage from capitalism to socialism is the organisation of industry in such manner that it produces as much as possible with the least expenditure of labour. We must raise technics, and the organisation of work, to a higher level.

As soon as the working class proves that, under the conditions imposed by the workers’ dictatorship, it can organise labour and the workers better than Ford and the other capitalists, then it has solved the knottiest problem of the October revolution, then it can demonstrate in a manner visible to everyone, by the proofs offered by actual economic practice, the advantages of our system as compared with the capitalist system in this most difficult of questions.

In our present position it is scarcely possible for us to tackle the question of the productivity of labour as it should be tackled, for it is a task involving the reconstruction of our industry, the perfecting of our technical equipment, the solution of the question of removing the factories to the vicinity of the sources of fuel and raw materials, the question of electrification, etc. It further involves the restoration of the basic capital of industry. The degree to which we can increase the productivity of labour at the present time, the number of improvements which we are able to introduce, are limited by the means at our disposition. Of the series of tasks confronting us, the one most possible of accomplishment for us at the present juncture, with our present means, is the increase of the productivity of labour on the given level of productive powers. This is the question of the moment, or we have the means for its immediate solution at hand, whilst the other possibilities–electrification, complete re-equipment of our whole industry with the newest machines and tools are dependent upon the possibility of raising extensive means, that is, from the accumulation of our capital. In order to come into possession of this capital, we must build upon that basis of production already at the disposal of the workers and peasants. The accumulation of surpluses and the gradual growth of the wealth of the country will enable us to cope with all the other tasks.

It is only by means of a rapid increase in the productivity of labour that we can hope to solve all the other cardinal questions. The fate of the dictatorship of the working class depends greatly upon this. For if the workers’ dictatorship does not give the people, the peasantry, the whole 130 millions of the population of the Soviet Union, an object lesson that the work done in the factories improves under the dictatorship of the working class, that the products become cheaper, and that life becomes easier from year to year under Soviet rule then it will naturally be impossible for the dictatorship to be maintained.

How is the Alliance between Town and Country to be Realised?

The alliance between the working class and the peasantry is spoken of everywhere today. Whatever may be the question under discussion, whether it be a question touching the development of industry, of the price of cotton, or anything else in the sphere of economics, it is invariably viewed from the standpoint of the alliance between the workers and the peasants.

Why it this inevitable precisely now? The workers accomplished the October revolution with the aid of the peasants. Peasants and workers together fought the civil war and defeated the landowners and the bourgeoisie. At this time a certain political contact existed between the two classes, a political alliance. But if we observe economic life during the period of war communism, we see that during this period the peasantry lived independently, that it had practically no connection with the working class in the towns, either in respect to goods traffic or cultural relations.

Torday this is completely changed. Town and country are connected by a thousand ties. The restoration of agriculture of which I have spoken signifies that the peasantry begins to make enormous demands for the products of the towns, cultural values and economic values alike. Tractors, ploughs, etc. are in great demand. This revival of agriculture, striven for eagerly by the peasantry, is only imaginable if town and country combine.

The Working Class must Lead the Peasantry.

The peasant follows the happenings in the cities with the greatest attention. He knows how much the working man has to work and how he lives, he knows that the workers have convalescent homes, children’s nurseries, etc. The working class in the towns knows much less about the life of the peasantry. The interests of the alliance demand that the workers regard it as one of their duties to learn more of the life and needs of the peasants. The working class, the trade unions, the workers organisations, and the Party, must prove themselves to be the leaders of the peasantry in actual reality, and lend economic and cultural support alike. If this is not done, then the various links of the ever lengthening chain connecting town and country will lead to very unsound results. Thus the chief slogan of working class policy towards the peasantry is expressed in the words: “Look to the country”! The observance of this slogan has never been so important as it is now. The mutual bounds between the interests of town and country have already become very strong. But it is necessary that the working class learn to comprehend the peasantry and their needs to a wider extent than has hitherto been the case. (Enthusiastic applause).

After an animated discussion on comrade Rykov’s speech, in which the debaters dealt chiefly with the punctual payment of wages, the situation in the metal industry, the production programme, the distribution of state orders among industrial undertakings, the co-operatives, and transport questions, and in which almost every speaker made some mention of the productivity of labour, comrade Rykov replied with a closing speech, dealing in detail with all questions raised by the debaters.

After this comrade Vladimirov gave a report on the details of the tariff and economic policy of the trade Unions. The intense interest roused by comrade Rykov’s speech was shown by several hundred written questions sent up to him before he made his closing speech.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly. Inprecorr is an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1924/v04n85-dec-16-1924-Inprecor-loc.pdf