Staying in China for three months during the tumultuous year of 1927, Nearing gives a precise, valuable summary of British imperialism’s history in China, including the role of its rivalries with the U.S. and Japan among others.

‘British Imperialism in China’ by Scott Nearing from The Daily Worker. Vol. 4 No. 175. August 6, 1927.

1. British Economic Interests in China.

BRITAIN’S early economic interests in China centred about the opium trade. The opium was produced in India and imported into China by the British East India Company, which had secured a monopoly of Chinese trade. The trade was not direct, however. It was carried on through a guild of Chinese merchants at Canton.

Opium imports increased rapidly. They were 200 chests in 1729. Between 1820 and 1828 opium imports doubled. Between 1828 and 1835 they doubled again. Again they doubled between 1835 and 1839. In the latter year British merchants imported 3,323,000 pounds of opium into China—about one hundred times the quantity that had been imported in 1729.

Meanwhile Chinese officials were doing what they could to stop a traffic that threatened to debauch the entire Chinese nation. In 1800 a series of imperial edicts were passed, prohibiting the importation of opium into China and also prohibiting its production in China. Despite these efforts, the trade grew.

In 1839 the Chinese government made a determined effort to stop the opium trade. A large quantity of opium was seized as contraband and destroyed, and British ships were forbidden to enter Cantonese waters. The result was the First Opium War (1840-1842). A good description of these episodes will be found in a book “China and the Nations,” by Wong Chin-wai, published in 1927 (Stokes, New York).

Another Chinaman, J.C. Yu, writes of the First Opium War: “China refused to allow England’s importation of opium. England imposed that importation on China by force. The right and the wrong are clear. No explanation is necessary.”

As a result of the First Opium War, China was forced to turn over Hongkong to Britain. This port was then used as a base for opium smuggling until, at the end of the Second Opium War, which began in the opium trade was legalized at the insistence of the British.

The First Opium War had another result that was of great consequence to the future of British economic relations with China. Four Chinese ports were “opened” to British traders.

The “opening” of Chinese ports meant that the Chinese merchant guilds no longer held the monopoly of trade. Instead they were forced to share the trading business with foreign merchants. The plan gave the British merchants an entrance into the Chinese market. It also laid the basis for an economic conflict that eventually brought on the Chinese Revolution of 1911.

British trade with China grew rapidly through the middle years of the last century. The yearly average was 10.4 million pounds sterling from 1851-1855; 16.8 million pounds from 1861-65, and 22.5 millions from 1871-75. There was a change in the balance and in the character of the trade, however. In the early years, British exports to China greatly exceeded British imports from China. By the end of the century, the situation had been reversed. The character of the trade had also changed. In the early years, the British merchants sold finished goods, ready for use, to the Chinese market. In the later year, the British manufacturer sold machinery to China, with which the goods for the Chinese market might be produced in China. This point is well made in a recent book “British Imperialism in China,” written by Elinor Burns, and published in London by the Labor Research Department. The value of British machinery exports to China was 8235,000 in 1875; $1,475,000 in 1895, and $2,630,000 in 1910.

In order to enable the Chinese to pay for these large amounts of capital goods, British bankers loaned money to China. The British share of loans made to the old Chinese governments is placed at $200,000,000. This, added to the private British capital investments, brings the total of British economic interests in China to about $1,500 million.

Here, in brief, is the economic basis of British interest in China. It is founded on trade and investments. Its object is economic profit to the British trader and investor.

2. The Flag Follows the Investor

Building this vast economic interest in China has been anything but a simple matter. It has taxed British Imperialism in China British diplomacy, and on numerous occasions has led to the use of British gun-boats, before solutions could be found for all of the knotty problems that arose out of the exploitation of China by British imperialists.

This intimate connection between the investor and the flag showed itself in:

1840-42–The First Opium War. Britain took Hongkong. Opened five Chinese ports to British trade.

1857-60–Second Opium War. Caused by Chinese seizure of an opium smuggler flying the British flag. Coast cities bombarded. Anglo-French troops took and looted Peking. More open ports and unequal treaties.

1862–Britain annexed lower Burma, a former tributary to China.

1886–Britain annexed upper Burma.

1890–Chefoo Convention. Britain secured control of the Yangtse Valley as a sphere of influence.

1899-1901–Boxer Rebellion. British, and other troops pillaged Peking and imposed a heavy indemnity on China.

A very good summary of these historic episodes will be found in “An Outline History of China,” by H.H. Gleason and Josef Hall, published by Appleton in 1926. In the aggregate they constitute the political subjugation of China by the imperialists, with the British well in the lead until 1914.

3. Japanese and American Rivalry.

Previous to the War of 1914, Britain found her economic position in China sharply challenged by the rival empires: Germany, Japan, United States. German hopes were blasted by the outcome of the war, but Japan and the United States remained. In 1913 16.5 per cent of the imports into China came from Britain, 20.3 per cent from Japan, and 6 per cent from the United States. When the war was over, and the costs counted, Britain had 9.6 per cent of the imports (1925); Japan 31 per cent and the United States 14.7 per cent. Meanwhile the Shanghai massacre, the killings by the British at Chameen and the bombardment of Wahnsien had aroused a storm of anti-British sentiment in China that was expressing itself in the Boycott of 1925. Thus the British imperialists in China found themselves face to face with a Japanese rival that must have the raw materials and markets of China in order to survive economically, and an American rival, with swollen coffers and immense surpluses that were seeking an outlet in China, as in every other available nook and cranny of the world.

British subjects had made extensive investments in China, and the British government had spent blood and treasure to safeguard and further those investments, only to find themselves face to face with the menace of imperial rivals who were just as ready to steal British ships and colonies in 1927 as British interests had been to steal German property in the preceding decade.

This was not the only menace to British imperial interests in China. British imperialism found itself face to face with the Chinese themselves: first, with the Chinese business men and later with the Chinese workers and farmers.

4. The Chinese Bourgeois Revolution.

Trade monopolies are very old in China. When the British first tries to sell goods in China they found that they must operate through Chinese merchant guilds which held a monopoly of trading. But this could not last. Beginning with the Treaty of Tientsin (1842) the British opened up one centre after another, set up their own shops and did their own trading in defiance of the Chinese merchants and their traditional monopoly.

The British went further. They not only took control of the Chinese customs, in conjunction with the other “Powers,” but they limited the amount of customs duties that the Chinese could charge to 5 per cent. Under these circumstances, the British manufacturer could make and dump goods on the Chinese market below the cost of hand-made native Chinese goods.

This line of action, on the part of British imperialists, placed the Chinese merchants and manufacturers in direct economic competition with the British interests. Add the fact that the British business men refused to pay taxes to the Chinese government, and that the British bankers dominated the world of credit, and a picture is painted of a Chinese business class quite at the mercy of the imperialists.

“But,” urges some objector, “did not the other imperialists do the same thing?”

Of course. The British were no more inherently imperialistic than the others. They merely got to the scene earlier and had more at stake. The practices were those of imperialists the world over. The leaders, in this instance, happened to be British.

For years Chinese businessmen were forced to put up with this position of inferiority. In the meantime, they were adapting themselves to the new business system. Many went to foreign countries, such as Britain and the United States, and established prosperous businesses. The Chinese businessmen continued to exercise great influence in centres like Singapore, Manila and other Asiatic ports. And in China itself they were accepting the new methods of trade and industry, investing their own capital and competing actively with their western rivals.

The textile industry had been put on a factory basis faster than any other in China. The Chinese control 73 modern cotton mills, with 2,112,154 spindles, as against 5 British mills with 250,516 spindles, and 46 Japanese mils with 1,218,544 spindles. In other industrial lines, the Chinese do not occupy so strong a position, but it is evident enough that the Chinese business classes like those of Japan, can operate under the western methods.

Here is a new rivalry for British imperialism in China. Chinese businessmen desire to exploit the Chinese workers and the Chinese markets and resources. On every hand, however, they find themselves surrounded by the special privileges and monopolies of the foreign imperialists. It was this group in China that financed and in the main pushed through the Chinese Revolution of 1911.

To be sure, there were other elements in the situation than the opposition to the foreign economic interests. The new Chinese business classes wanted to free themselves from the semi-feudalism of the Manchu dynasty. But the slogan around which they most easily united was a common opposition to foreign domination of economic opportunities in China.

5. Facing the Chinese Workers.

British imperialism in China had another bill to meet–a bill presented by the workers of China. Chinese coolies had sweated on the docks while Chinese women and children had toiled in the mills, working for less than a bare living, and helping to swell the dividend roll of British investors. The conditions under which they labored had been intolerable. Many of the foremen were foreigners. They neither sympathized with the Chinese, nor did they spare them.

Pay was pitifully low. Colonel Malone has recently written a report for the British Independent Labor Party which is published under the title: “The New China.” Part II of this study was devoted largely to a very plain statement about wages, hours and working conditions. Here are some typical daily wage rates, expressed in terms of American money:

Cotton industry (men) 15 to 25 cents.

Railway workers, 25 cents.

Coal miners, 12 to 25 cents.

Match factories, (women) 5 to 25 cents; (children) 5 to 10 cents.

Silk factories (women) 20 cents; (children) 10 cts.

Hours are long. The twelve hour day and the seven day week are common. Many strikes have been called to reduce the working day to twelve hours. Sometimes it is as high as 16 hours. Little time is allowed for meals. Men, women and children as young as eight years work these hours.

Working conditions are bad. There is dust. Machinery is unprotected. Sanitation is inadequate. The worst conditions of exploitation in Britain in the early years of the nineteenth century are exceeded in China.

Foreign capital has exploited the workers of China under such conditions. Beginning with the Hongkong Seamen’s Strike of 1922 (Hongkong is British), the movement to organize the workers has spread rapidly over China.

Here is another menace facing the British imperialists in China–the mass movement of the Chinese workers. They have been aroused by the terrible conditions of work and life that have been enforced upon them. They have begun to use the strike and the boycott–with deadly effect. These masses have grown anti-foreign through years of suffering and hardship and humiliation suffered at the hands of the British-led imperialists.

6.The Soviet Menace.

British imperialists face still another menace in China: the menace of Sovietism. Until 1917 this menace was nonexistent. Since the Russian Revolution of 1917 it is one of the most serious of the forces that confront British imperialism in China. There are a number of reasons for this:

1. The Soviet system presents a view of social life that is very close to the experiences of the Chinese villagers. They understand the meaning of “committee government” because they have practiced something very like it.

2. Sovietism offers the Chinese masses a possible means of escape from the worst phases of private capitalist exploitation. What they have known of this system has convinced them of undesirability.

3. Sovietism is an appeal from a system of society that rewarded parasitism, to a system that emphasizes the desirability of productive and useful effort. The great mass of the Chinese are workers, and again this idea comes very close to their experience.

4. The Soviets have been emphasizing and practicing self-determination. In sharp contrast with the imperialists they have been demanding freedom in the cultural life of dependent peoples. The Chinese Nationalist movement is striving for just that freedom.

Thus the Soviet system, both because of the time when it is offered to the Chinese and because its character, appeals to the experience of the Chinese, has already had a great influence in shaping the thinking of the new Chinese Nationalist movement. The imperialists have been appealing with gunboats. The Soviets have been appealing with offers of co-operation and suggestions that Russia and China make a common stand against imperial aggression.

7. China As A Battle Ground.

With the entrance of the Soviet Union on the scene, China become a battle ground across which some of the most important non-military engagements in modern history were fought. Military battles were fought, but they were incidental. The major struggle was waged between different levels of social development.

Three principal interests were contending for supremacy in China:

1. The imperialists, led by Great Britain. Their watchword was “law and order,” which, in this instance, meant the continuance of the unequal treaties, of imperial control of the Chinese customs, of the consular courts, of the exploitation of China by foreign business interests. This era was ushered in officially by the First Opium War of 1840-42. It continued until the beginnings of the modern Chinese Nationalist movement in the Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

2. Chinese Nationalism found vigorous expression in 1900. It broke out again in rebellious protest in the Revolution of 1911. It developed its most widespread expression in the mass demonstrations against imperialism that occurred in 1925-27. The rallying cry of the Nationalist movement was: “China for the Chinese; abolish inequality and privileges; put China in her rightful place among the nations.”

3. The Soviet Union influence crystallized about the Russo-Chinese Treaty of May 31, 1924. Encouragement, advice and assistance were given by the Soviet Union to aid China in her struggle for independence. Great stress was laid upon the organization of the Chinese labor movement. Hope was held out for the establishment of a Pan-Asiatic bloc with a united front against imperialism. Soviet spokesmen suggested: “China for the masses of Chinese wage-earners and farmers; China as a link in the chain of the new social order.”

Summarized in three words, Imperialism, Nationalism and Sovietism were struggling for control in China. After the First Opium War, imperialism had things pretty much its own way. Between 1900 and 1920 Chinese nationalism asserted itself more and more positively, with the needs and the demands of the Chinese business class as a basis. After 1920 the workers and farmers of China, organizing under the Three Principles of Sun Yat Sen, and with the help and encouragement of the Soviet Union, made a strong drive for the control of the country.

8. What Shall the Imperialists Do?

Imperialism came to China armed with machine technology and with a science of economic, social and military organization which far surpassed’ anything known to the Chinese. The imperialists came with a different culture, and had China been as small and as easily unified as Japan, it is probable that within a generation or two China, like Japan, would have become a modem empire. But China was neither small nor united. Unlike Japan, and like India, and other portions of Asia, China was grabbed piecemeal by the imperialists who, for generations, did with China practically what they pleased.

During the years that followed the Chinese Revolution of 1911, imperialism, which had already made its mark in China, was, in a sense, on trial. Had the imperialists been able to adjust themselves to these trial conditions, they might have still remained for a comparatively long period, because of the weakness of China and the lack of centralization in the Chinese government, but the imperialists were unable to play the role. They were in China to exploit China and the Chinese. They knew no other method of procedure.

The Japanese led off by seizing Shantung. The other empires followed suit by validating the seizure in the Treaty of 1919. Then came the episodes with British imperialism than culminated in the Shanghai massacre and the bombardment of Wahnsien. The British at Hongkong outlawed the labor unions and suppressed meetings among the Chinese. British police arrested active members of the Kuomintang Party and turned them over to the Northerners to be executed. British imperialism became a rallying point for the reactionary forces in China.

That, in essence, is the role that British imperialism is playing in China at the present time. It upholds special privilege and inequality. It opposes the movement for Chinese Nationalism. With all of its energies and resources it is combatting the influence of the Soviets. It is doing its best to prevent the organization of Chinese workers and farmers.

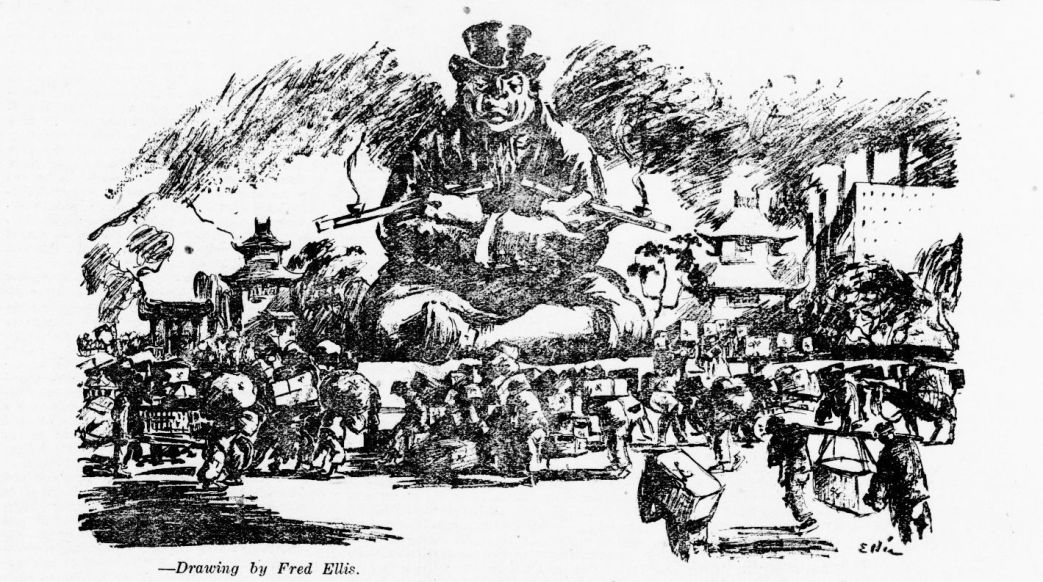

The British imperialist in China, like his fellow-imperialist in Inda, wants to keep China in leading strings in order that she may be more readily exploited by trader, manufacturer, contractor and banker. British imperialism, supported, to a degree by the American and the Japanese empires, is the arch enemy of the Chinese masses in their efforts to establish a free China under the control of an organized working class.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1927/1927-ny/v04-n175-NY-aug-06-1927-DW-LOC.pdf