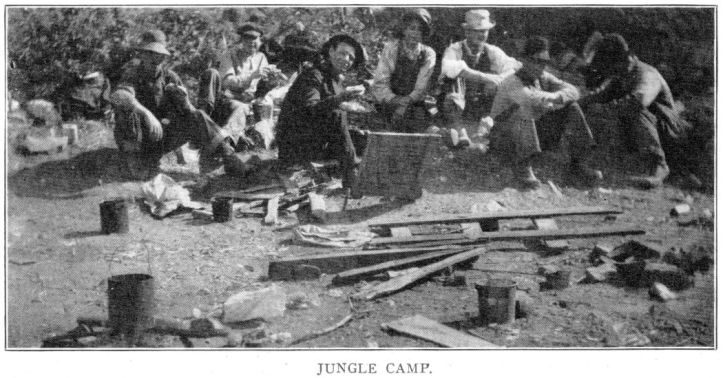

A wonderful, evocative article by long-time I.W.W. activist E.F. Doree on the now lost world of mass, migratory grain harvesters; riding the rails, the Agricultural Workers’ Organization, their ‘jungle camps,’ and traveling wobbly proselytizers of the One Big Union.

‘Gathering the Grain’ by E.F. Doree from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 15 No. 12. June, 1915.

THE great, rich wheat belt runs from Northern Texas, through the states of Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska, South and North Dakotas, into Canada, and not a few will point with pride to the fact that last year WE (?) had the largest wheat crop in the history of this country. But few are the people who know the conditions under which they work who gather in these gigantic crops. It is the object of this article to bring out some of these vital facts.

About the middle of June the real harvest commences in Northern Oklahoma and Southern Kansas. This section is known as the “headed wheat country,” that is to say, just the heads of grain are cut off and the straw is left standing in the fields, while in the “bundle country” the grain is cut close to the ground and bound into sheaves or bundles.

In the headed grain country the average wage paid is $2.50 and board per day, but in the very end of the season $3 is sometimes paid, the increase due to the drift northward of the harvest workers, who leave the farmers without sufficient help. This is not a chronic condition, as there are usually from two to five men to every job.

The board is average, although fresh meat is very scarce, salt meat being more popular with the farmer because it is cheaper. Most of the men sleep in barns, but it is not uncommon to have workers entering the sacred portals of the house. Bedding of some kind is furnished, although it is often nothing more than a buggy robe.

The exceedingly long work day is the worst feature of the harvesting so far as the worker is concerned. The men are expected to be in the fields at half past five or six o’clock in the morning until seven or half past seven o’clock at night, with from an hour to an hour and a half for dinner. It is a common slang expression of the workers that they have an “eight-hour work day” — eight in the morning and eight in the afternoon.

Most of the foreign-born farmers serve a light lunch in the fields about nine o’clock in the morning and four o’clock in the afternoon, but the American farmers who do are indeed rare.

In this section the workers are sometimes paid so much per hundred bushels, and the more they thresh the more they get. On this basis they generally make more than “goin’ wages,” but they work themselves almost to death doing it. No worker, no matter how strong, can stand the pace long; the extremely hot weather in Kansas proves unendurable. Twenty- five men died from the heat in one day last year in a single county in Kansas.

The workers threshing “by the hundred” must pay their board while the machine is idle, due to breakdown, rain, etc.

About the time that the headed grain is reaped the bundle grain in Central and Northern Kansas and Southern Nebraska is ready for the floating army of harvesters.

Here the wages range from $2 to $2.50 and board per day. They have never gone over the $2.50 mark. Small wages are paid and accepted because thousands of workers are then drifting up from the headed wheat country and because of the general influx of men from all over the United States, who come to make their “winter’s stake.” This is about the poorest section of the entire harvest season for the worker. The following little story is told of the farmers of Central Nebraska:

“What the farmers raise they sell. What they can’t sell they feed to the cattle. What the cattle won’t eat they feed to the hogs. What the hogs won’t eat they eat themselves, and what they can’t eat they feed to the hired hands.”

In Nebraska proper the farms are smaller, as a rule, than elsewhere in the harvest country and grow more diversified crops. Almost every farmer has one or more “hired men,” and for that reason does not need so many extra men in the harvest, but in spite of this, the whole floating army marches up to get stung annually. Most of the “Army From Nowhere” cannot get jobs and have a pretty hungry time waiting for the harvest farther north to be ready. ‘The farmers in South Dakota do not believe in “burning daylight,” so they start the worker to his task a little before daybreak and keep him at it till a little after dark. If the farmer in South Dakota had the power of Joshua, he would inaugurate the twenty-four-hour workday.

The wages here range from $2.25 to $2.50 and board per day, while in isolated districts better wages are sometimes paid. A small part of the workers are permitted to spend the night in the houses, but most of them sleep in the barns. Sometimes they have only the canopy of the heavens for a blanket.

As soon as the harvest strikes North Dakota wages rise to $2.75 or $3.50 and board per day, the length of the workday being determined by the amount of daylight.

The improved wages are due to the fact that thousands of harvesters begin leaving the country because of the cold weather, and the fact that the farmers insist on the workers furnishing their own bedding. At the extreme end of the season wages often go up to as high as $4.00 and board, per day.

The board in North Dakota is the best in the harvest country, which is not saying much.

In North and South Dakota no worker is sure of drawing his wages, even after earning them. Some farmers do not figure on paying their “help” at all and work the same game year after year. The new threshing machine outfits are the worst on this score, as the bosses very seldom own the machines themselves and, at the end of the season, often leave the country without paying either worker or machine owner.

This, however, is not the only method used by the farmers to beat the tenderfoot. In some cases the worker is told that he can make more money by taking a steady job at about $35.00 a month and staying three or four months, the farmer always assuring him that the work will last. The average tenderfoot eagerly grabs this proposition, only to find that thirty days later, or as soon as the heavy work is done, the farmer “can no longer use him.” There have been many instances where the worker has kicked at the procedure and been paid off by the farmer with a pickhandle.

The best paying occupation in the harvest country is “the harvesting of the harvester,” which is heavily indulged in by train crews, railroad “bulls,” gamblers and hold-up men.

Gamblers are in evidence everywhere. No one has to gamble, yet it is almost needless to say that the card sharks make a good haul. Quite different is it, though, with the hold-up man, for before him the worker has to dig up and no argument goes. This “stick-up” game is not a small one, and hundreds of workers lose their “stake” annually at the point of a gun.

As is the rule with a migratory army, the harvesters move almost entirely by “freight,” and here is where the train crews get theirs. With them it is sim- ply a matter of “shell up a dollar or hit the dirt.” Quite often union cards are recognized and no dollar charged, and the worker is permitted to ride unmolested.

It is safe to say that nine workers out of every ten leave the harvest fields as poor as when they entered them. Few, indeed, are those who clear $50.00 or more in the entire season.

These are, briefly, the conditions that have existed for many years, up to and including 1914, but the 1915 harvest is likely to be more interesting if the present indications materialize.

The last six months has seen the birth of two new organizations that will operate during the coming summer. The National Farm Labor Exchange, a subsidiary movement to the “jobless man to the manless job” movement, and the Agricultural Workers’ Organization of the Industrial Workers of the World.

The ostensible purpose of the National Farm Labor Exchange is to handle the men necessary for the harvest systematically, but its real purpose is to flood the country with unnecessary men, thus making it possible to reduce the wages, which the farmer really believes are too high. If the Exchange can have its way, there will be thousands of men brought into the harvest belt from the east, and particularly from the southeast. It is needless to say that these workers will be offered at least twice as much in wages as they will actually draw.

News has come in to the effect that the farmers are already organizing their “vigilance committees,” which are composed of farmers, business men, small town bums, college students and Y.M.C.A. scabs. The duty of the vigilance committee is to stop free speech, eliminate union agitation, and to drive out of the country all workers who demand more than “goin’ wage.”

Arrayed against the organized farmers is the Agricultural Workers’ Organization, which is made up of members of the I.W.W. who work in the harvest fields. It is the object of this organization to systematically organize the workers into One Big Union, making it possible to secure the much needed shorter workday and more wages, as well as to mutually protect the men from the wiles of those who harvest the harvester.

The Agricultural Workers’ Organization expects to place a large number of delegates and organizers in the fields, all of whom will work directly under a field secretary. It is hoped this will accomplish what has never been done before, the systematization of organization and the strike during the harvest, as well as the work of general agitation.

Both of these organizations intend to function so that the workers in the fields will have to choose quickly between the two. If the farmers win the men to their cause, smaller wages will be paid and the general working conditions will become poorer; if the workers swing into the I.W.W. and stand together, then more wages will be paid for fewer hours of labor. Both sides can’t win. Moral: Join the I.W.W. and fight for better conditions.

Mr. Worker, don’t do this year what you did last, harvest the wheat in the summer and starve in breadlines in the winter. Let us close with a few “Don’t’s.”

Don’t scab.

Don’t accept piece work.

Don’t work by the month during harvest.

Don’t travel a long distance to take in the harvest; it is not worth it.

Don’t believe everything that you read in the papers, because it is usually only the Durham.

Don’t fail to join the I.W.W. and help win this battle.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v15n12-jun-1915-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf