The impact of the automobile and associated industries on all of our lives has been just that. It is about our lives. It has always been known that leaded gasoline is a poison to workers, consumers, and the general public. How the profits of the fuel companies have trumped all of our lives. It was not until 1996, seventy years after this article, that the U.S. banned leaded gasoline.

‘Ethyl Gas: Why Is She Back and What Does It Mean?’ by N. Sparks from The Daily Worker. Vol. 3 No. 204. September 11, 1926.

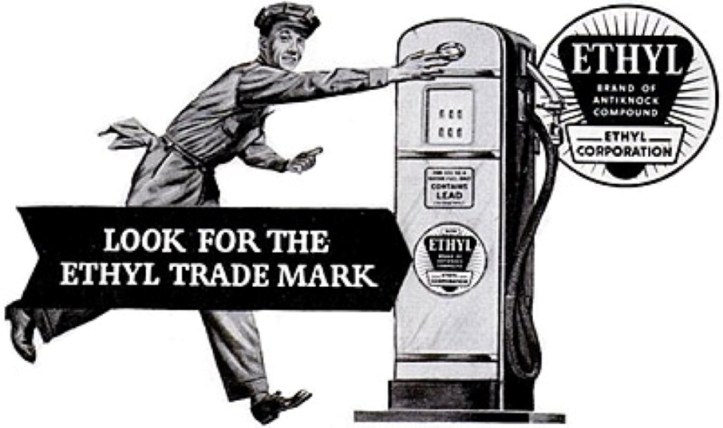

“LET’S all heave a sigh of relief. Ethyl is back!” There are big signs up around the Standard Oil filling stations telling us so. It looked pretty bad at one time with the newspapers kicking up all that fuss and calling it “looney gas.” But now, thank goodness, the trouble’s all over! They had an investigation and now everything is sitting pretty. Ethyl is back.

“Of course, if you’re a garage worker, maybe it isn’t so good. And if you work in one of the stations where they mix that stuff into the gasoline you may have to be pretty careful. And if you work in one of the plants where they actually make the tetraethyl lead—but there’s only a bunch of bohunks work there, and they don’t matter. What does matter is the great automobile-owning public that you get the profits out of. Ethyl gasoline gives them more miles for their dollar, and that’s what counts.”

Being rather scantily represented in the great automobile-owning public (to the tune of a few second-hand Fords here or there) we fail to burst into cheers at this information. In fact we are still inclined to ask: “What is the necessity for inflicting a new and deadly poison upon society—a poison to which thousands of workers will be particularly exposed?

Why can’t people go on using ordinary gasoline to drive their cars? Well, the answer is: Tetraethyl lead (which is the substance that is mixed into ordinary gasoline to make ethyl gasoline) is an anti-knock. Unfortunately most of us don’t even know what a knock is—let alone an antiknock.

So let us go back to the beginning and find out just to what extent tetraethyl lead is indispensable to the advance of industry and civilization. Let us assume that you know some member of the great automobile-owning public—know him well enough to get him to take you for a ride. Notice the sound of his engine as you travel at medium speed. And now notice it as you travel fast, especially when climbing a hill. Besides the ordinary sound of the engine you will hear a distinct “Ping!” in every cylinder.

Now we have it! That is the knock! That “Ping!” sounds just as though something were knocking Inside the cylinders, and if your friend cares much for his car he will slow down and maybe shift gears. Now, of course, the next thing we want to know is: What causes the knock and what harm does it do? An automobile is driven by the combustion of a mixture of gasoline vapor and air in each of the cylinders. This combustion is very rapid, so that it is often called an explosion. But this is not really correct. The flame takes a small but distinctly appreciable amount of time to travel the length of the cylinder. An explosion, however, is practically instantaneous.

And right here is where the knock comes in. When the machine is going at high speed, the mixture no longer burns quietly, the flame no longer travels uniformly thru the length of the cylinder. Instead, the mixture starts to burn, but then the rest of it explodes, making that “Ping!” or knock that we heard. So we see that the knock is caused by the fact that part of the fuel explodes instead of burning. And an anti-knock is something we can add to the fuel which will have the property of preventing that explosion, slowing it down into a uniform combustion.

Now what harm does the knock do? First, it causes excessive wear on the engine. Second, it reduces the efficiency (i.e., makes necessary more fuel for a given distance), for the sudden impact of the explosion on the piston and cylinder walls is not nearly as effective as the steady push on the piston caused by a proper combustion.

These things are bad, but we must find something worse yet if we are to explain the common statement that the knock stands in the way of progress. Even the best automobile is not a very efficient machine—that is, only a small percentage of the energy contained in the fuel used is actually transmitted to the wheels. Increasing efficiency means saving fuel, and the conservation of oil fuel is becoming a problem of tremendous importance.

There is a tendency among automobile engineers today to believe that the first great step towards increasing efficiency is to increase the compression in the cylinders. And, true enough, when very much higher compression is used in the motor much more power is obtained from the same quantity of fuel. But the knock! Alas! with increased compression the knock also increases. So much so that all talk of higher compression becomes useless unless the knock can be eliminated. And so the automobile engineer’s dream of conserving oil by producing only high-compression motors has to wait for the production of an effective anti-knock compound. So now we can see the setting of the scene into which tetraethyl lead, this standard-bearer of progress, burst in the years 1924 and 1925, poisoning, paralyzing and killing workers, driving them into convulsions and frightful insanity.

Tetraethyl lead, as an antiknock, was discovered by Thomas Midgely. Jr., a chemist on the staff of the Standard Oil. A new concern was created, the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation, half of the stock owned by the General Motors and the other half by Standard Oil. The Ethyl Gasoline Corporation was thus a child of both Morgan and Rockefeller. To the vice-presidency of this million-dollar corporation, Thomas Midgeley, Jr., a young man well under thirty, was elevated. Thomas Midgeley, Jr., could congratulate himself that his position for a young man of his age was absolutely unique, and his fortune was made. Standard Oil could congratulate itself that it would soon drive all competing gasolines off the market. General Motors could congratulate itself that it would soon introduce high-compression motors and all other makes of cars would become utter back numbers.

Into these happy dreams, however, burst from time to time a rude interruption; the report of a death here and there in the Du Pont plant at Deepwater, N.J., where the tetraethyl was being manufactured, or in the Ohio district where it was being unostentatiously distributed, a couple of cases of insanity, a few paralyses. It was not the accidents that mattered so much (the company was fully aware of the deadliness of the substance it was handling), but the fact that despite all precautions, rumors would leak out and get into the papers.

The company began a halfhearted, uneasy investigation into the accidents. It approached prominent experts on physiological chemistry and then drew back again. If the thing ever got into the papers it would be all up, with a vengeance. Suddenly came the Bayway tragedy. A dozen or so men working in the Bayway refinery of the Standard Oil suddenly went into hideous convulsions and violent insanity and had to be removed to the hospital. The whole affair burst into publicity. The doctors were forced to admit that the victims were suffering from acute lead poisoning due to inhalation of tetraethyl lead fumes. The New York World scented a good thing, took np the name “looney gas,” which the workers had christened it, spread it all over the front page and announced that it was beginning a campaign against it. Other papers were forced to come along. Thomas Midgeley, Jr., and his staff made heroic efforts to stem the tide. Time and again they announced that the only hazard was in manufacture, that it was only workers who would go insane; but the great automobile-owning public saw themselves going into convulsions and dying from using this gasoline in their cars and grew hysterical with fear, in vain Thomas Midgeley, Jr., gave an impressive demonstration to the reporters. To show its harmlessness to the user he called for a can of his beautiful red ethyl gasoline and washed his hands in it (carefully drying them off at once). All to no avail. Maybe it was only red ink he had washed his hands in. Maybe getting it on your hands didn’t matter. The hysteria mounted. Ethyl gasoline was barred in New York. Thomas Midgeley, Jr., Standard Oil, General Motors, saw their dreams vanishing. To forestall complete prohibition, the Ethyl Gasoline Corporation announced that they would voluntarily discontinue the sale of their product pending the result of an investigation. On all sides the cry of “investigation!” was taken up. The surgeon-general of the United States was instructed to call a preparatory conference. The Ethyl Gasoline Corporation breathed freely again. At last they were on safe and familiar ground.

Before adjournment to the surgeon-general’s conference, let us consider the different varieties of lead poisoning offered to its makers, distributers and users by tetraethyl lead. Until the advent of tetraethyl only the chronic form of lead poisoning had been known. This is the form to which painters, typesetters and others who work with ordinary compounds of lead are exposed. Lead is what is known as a “cumulative poison.” That is, a small amount of lead taken once does not act as a poison; but if even a tiny amount is taken into the body day by day, it accumulates in the tissues and gradually in the course of months or years, produces “lead drop,” “lead colic,” paralysis and sterility. With the tetraethyl, however, one exposure is plenty. Tetraethyl lead is a liquid and is readily absorbed by the skin. Furthermore, tetraethyl lead presents lead in a highly volatile form, i.e., it easily turns into vapor. In this form it can be inhaled in large quantities. Whether absorbed thru the skin or the lungs, it distributes itself almost immediately throughout ‘the body. The lead reaches the brain, and convulsions, insanity and death are the result. This is acute lead poisoning.

The workers in the factory whore the tetraethyl lead is made have a chance both at the acute poisoning from the product and chronic poisoning from the other lead compounds and lead dust lying abound. The workers in the blending stations where the tetraethyl is mixed with gasoline to make the ethyl gasoline have a good chance at both acute and chronic poisoning. The great automobile-owning public has a fair chance at chronic poisoning. And should the use of ethyl become general even those who walk the streets and have to breathe the sweet air of innumerable automobile exhausts would stand a fair chance of chronic lead poisoning.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1926/1926-ny/v03-n204-supplement-sep-11-1926-DW-LOC.pdf