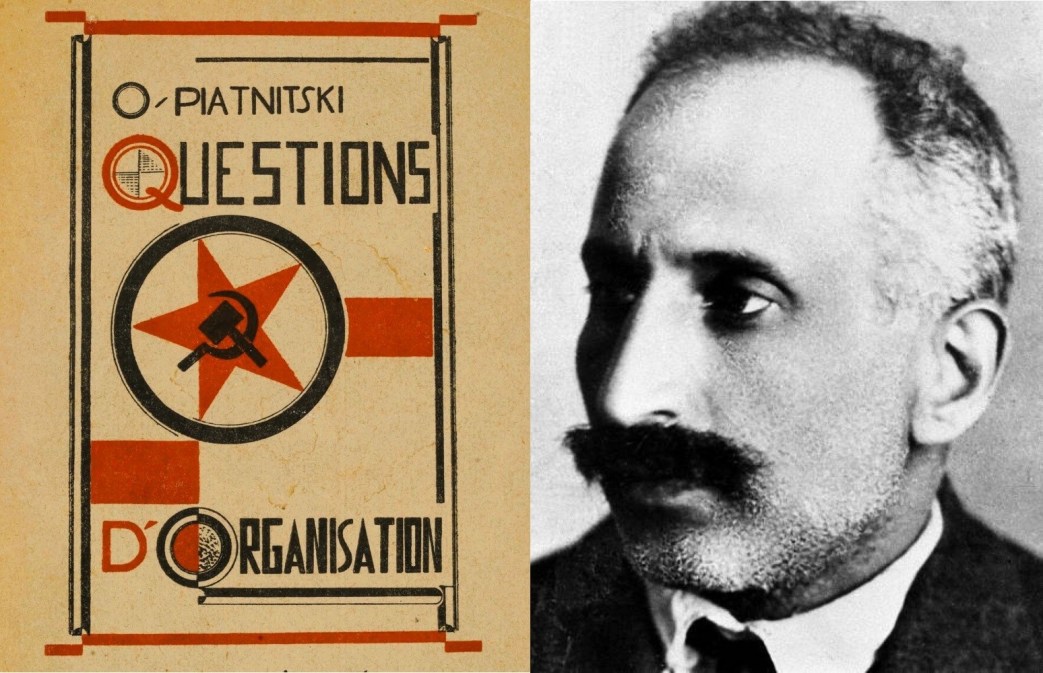

Central to the process of reorganization, ‘Bolshevization,’ in the mid-1920s, Piatnitsky looks at the exemplary difficulties in the German, Italian, and Czecho-Slovak parties. Osip Aaronovitch Piatnitsky was born Iosif Aronovich Tarshis in today’s Lithuania in 1882. The son of a Jewish carpenter, Osip followed in the trade and became a member of illegal unions and the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party at 16. In Vilnius he became a leading activist in the ladies’ garment workers union and took “Piatnitsa” (“Friday”) as his underground name. In 1901 he joined Lenin’s Iskra group and moved to Germany where he sided with the Bolsheviks during the 1903 split. Returning to the Russian Empire, he was active in the 1905 Revolution, leading the Odessa general strike. Jailed until 1908, Piatnitsky returned to Party work in Germany and France, where he also trained to become an electrician. Back again in Russia by 1913, he was arrested and exiled to Siberia shortly before the outbreak of World War One. Released in the February Revolution of 1917, Piatnitsky moved to Moscow where he joined the Party’s Moscow Committee helping to lead the October Revolution in that city. In 1920 he was first elected as alternate to the Communist Party’s Central Committee and began his long work on the leadership of Communist International in 1921. Replacing Zinoviev’s Comintern leadership in 1926, he sat on the four-person Secretariat in 1926 until 1935. Elected as a full member of the CC in 1927, he was at first loyal to the leadership group around Stalin though fell from power with the rise of Dimitrov and the Popular Front at the Seventh World Congress in 1935. Refusing to support the Purges and openly rejecting the veracity of the NKVD’s claims at a CC Plenum to endorse the Purges. Arrested, he refused to recant, even after torture. Comrade Osip Piatnitsky was executed a year later on October 30, 1938 at 56 years old.

‘Organisational Problems of Comintern Sections’ by Osip Piatnitsky from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 4, July-August, 1924.

Influence of Communist Parties on the Working Class.

WHILE the influence of the various Comintern sections on the working class of their respective countries is very great, they have failed so far to establish strong organisational connection with the masses of workers. In Rumania and Yugo-Slavia, in spite of the persecution of the Communist Party by the regular and secret police, while they protect the social democracy, the Communists have the support of the Trade Unions and yet neither the Yugo-Slavian nor the Rumanian Communist Party has well-organised Communist factions in the unions, nor party nuclei in the factories and shops.

The above mentioned applies to a greater degree to the Czecho-Slovakian and German parties. In the last municipal elections in Czecho-Slovakia (exclusive of trans-Carpathian Ruthenia) the Czech Party came out second to the government party in the number of votes received, and in the recent elections in trans-Carpathian Ruthenia the Czech Party received 40 per cent. of the votes cast. But it is doubtful whether the party has the organisation to consolidate its influence over the proletariat and poor peasants of Czecho-Slovakia.

As regards Germany, the October retreat, in my opinion, was mainly due to the fact that the German Communist Party has not effected a close organisational alliance between the local party organisations and the masses of the workers in the factories, shops and mines, etc., and was therefore unable to gauge the mood of the masses correctly. At the present time the influence of the German Communist Party on the masses has not decreased, in spite of the fact that the factory and shop owners have remained absolute masters of their enterprises, and in spite of the fact that there is great unemployment and that practically all the active Communists have been driven from the factories and shops, where party nuclei are practically non-existent. At the elections of the factory committees the German Communist Party received no less than 50 per cent. of all the votes, while the Social-Democrats, the Christian Socialists (Catholics), the Hirsch Dunker trade unions (Liberal), the non-party and the Fascisti tickets received all together not more than 50 per cent. of all the votes cast. (Information on the exact results of the factory committee elections is still lacking, but in the Ruhr and in the large factories and shops the Communist candidates received the majority.) And in the elections in Thuringia (to the Landtag), in Saxony (in the urban and rural council elections), and in Bavaria (to the Landtag), the Communist Party received about a million votes (in Bavaria, thanks to the Fascist terror, there was practically no party organisation, but the Communist Party nevertheless, received four times as many votes as it had in the last elections in 1920—200,000 as against 50,000 votes).

To my mind it is doubtful whether the German Communist Party will be able to consolidate organisationally its influence on the working class of Germany for future combats, if it retains its presents form of organisation.

Forms of Organisation in Comintern Sections.

The Comintern sections all over the world, excluding those countries which were formerly a part of the Russian Empire (Poland, Finland, Esthonia, Latvia, and Lithuania), do not differ in respect to form of organisation from the social-democratic parties and organisations existing side by side with them, notwithstanding the fact that the aims of the Social-Democrats and the Communists are profoundly different.

The Social-Democrats need an electoral machine, therefore their party is built up on the basis of residential electoral constituencies. For the Communists the important question is to draw the whole working class into the active struggle against capitalism and its leaders, and to seize control of the apparatus of production and the state. Therefore, the basis of the party organisation must be party nuclei in the factories, mines, workshops, offices, stores—in a word, wherever workers by hand and by brain are employed. Elections for parliament, municipalities, etc., serve the Communists mainly as a means for propagating the ideas of Communism, and for testing their influence on the masses. Because the Communists have adopted the social democratic form of organisation rather than shift the centre of gravity of all party work to the factories, the Communist Parties are unable to cement organisationally their enormous influence on the working class, they are unable to judge the mood of the masses correctly and to lead them into the struggle at the decisive moment.

In order not to confine myself to generalities, I will give specific examples of the forms of organisation in several countries: Italy, Czecho-Slovakia and Germany.

Italy. Let us take the industrial city of Turin. The form of organisation there is as follows. The city is divided into sectors, the sectors are divided into zones, the zones are divided into groups to which belong the members of the party living in the given zone. These groups are the basis of the organisation. They consider all questions of Party life, they elect the delegates to the city and gubernia conferences, etc. The city committee appoints organisers in the sectors (one organiser to a sector). The latter appoint organisers in the zones (one to a zone). The functions of the organisers of the sectors (and zones) are merely to maintain connections between the city party committee and the groups, and to keep the addresses of the zone organisers. The latter keep the addresses of the secretaries or delegates of the groups. Party nuclei still exist in the factories of Turin, but they neither discuss nor decide Party questions. Their entire work consists in the distribution of literature and recruiting new members for the Party. The members of the nuclei belong to the groups according to their place of residence, and only in the group do they decide party questions. Under this form of organisation it very rarely happens that members working in the same factory and belonging to the same factory nuclei, belong also the same district group. Is it possible with such an organisation for the Turin Party Committee to organise properly, to expend and distribute its work, to keep correctly informed on the mood of the workers, and intervene in economic conflicts in the factories? Certainly not. It is not surprising that the members of the party nuclei in Turin have begun to talk of uniting all the factory nuclei of Turin into a special party organisation, parallel to the one already existing. The Italian comrades seized eagerly upon the January instructions of the Executive Committee of the Comintern regarding the organisation of nuclei in the factories and offices, and their rights. If it had not been for this there might have been a conflict between the factory nuclei and the groups in Turin.

Czecho-Slovakia. The entire party organisation over all of Czecho-Slovakia is built up at the present according to electoral districts. There are neither party nuclei in the factories, nor Communist fractions in the trade unions, in spite of the fact that since the Fourth Congress, the Executive Committee of the Comintern has held several conferences with delegations from the Czech Communist Party on the question of the organisation of nuclei, and that several letters of instruction have been sent them on the same question. This is explained by the fact that the local party organisations in Czecho-Slovakia are so conservative on this question that they regard with great suspicion the transition to a new form of organisation, the formation of nuclei in the factories and shops. The comrades on the committee of the Prague organisation declare that they have directed the local party organisations very well for thirty years, and that they have combated the enemies of the working class very successfully, and, therefore, there is no need to change the form of organisation. We quite understand that it is very difficult for the Prague comrades to part with their old form of organisation, but it is necessary to reckon with facts. No sooner had the Young Communist League built up its organisation on the basis of nuclei in the factories, than they enrolled in a very short period of time 400 new members from the factories and shops, and in 1920, when the Czech proletariat were waging their heroic struggle with the bourgeoisie under the direction of the Czech Communist Party, the latter had its main support in the factories. In spite of the splendid results of the direct union of the Communist Party with the factories and shops in 1920, the old traditions gained the upper hand and the Czech party as a whole reverted to the idea of organising the party according to electoral divisions, based on the place of residence of the voter. Recently, since receiving the regulations of the Executive Committee of the Comintern in regard to the formation of nuclei, a discussion has commenced in the party press and in party conferences on the question of re-organising the party.

Germany. In Germany the discussion of the question of organising nuclei in industrial enterprises has been going on for more than a year both in the periodical literature and at meetings. In some places the factory nuclei already exist, but there is not a single city entirely organised in this way. In those places where the nuclei exist, they have no party rights whatever, and along with them exist geographically organised party groups. Practically all the active workers of the German Communist Party recognise the necessity of re-organising the party, but they are hampered on the one hand by conservatism or predilection for the old form of party organisation and on the other by the disagreements which have recently taken place in the German Communist Party. We take only the Berlin organisation, because it is typical of all the other local organisations of the German Communist Party. In Berlin there are two parallel organisations to which the Berlin Committee of the party is responsible. The Berlin organisation is divided into districts, and in each district there are groups organised according to the place of residence of the party members. These groups consider (and unfortunately all too rarely and not in sufficient detail) and decide party questions. These groups elect delegates to the Berlin party conferences. Parallel with these groups and the district conferences in Berlin there exists “functionaries” (active workers). These include the active workers in the party, in the trade unions, the co-operatives, the factory committee movement, etc. The meetings of active workers consider and make decisions on all party questions. This institution of functionaries plays a harmful role in the German Communist Party, for the following reasons:

First, the functionaries consider and decide all party questions without having been delegated to do so by the members of the party;

Secondly, the party has created “priests” castes which take an active part in party affairs, while the remaining members of the party are entirely passive, and

Thirdly, a considerable section of the functionaries are entirely isolated from the masses, and their decisions do not always coincide with the opinion of the organisations as a whole.

Let us take for example the question which is a burning one for the German Communist Party, viz., the trade unions question. The Berlin Party conference, to which the party groups sent their representatives, decided by 95 to 15 votes against the splitting of and the withdrawal from the unions, but a few days after the party conference a large meeting of all the functionaries of Berlin—several thousand people—took place at which the resolution regarding the withdrawal of the Communists from the unions and organising a split within them received about half of the votes, and that after a series of concessions had been made on the point of the Berlin Party committee. The party can only formulate its general policy correctly, so that is corresponds to the interests of the working class, when all members of the party, and chiefly party members in the factories and offices, participate in the affairs of the party directly, and not through the functionaries.

Another example is to be found in the construction of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party (which is by no means the worst in the Comintern). Since November of last year the German Communist Party has been declared illegal and therefore the Central Committee was cut down to 11 members. The latter was divided into a political bureau and an organising bureau. From these two organs is composed the small plenum of the Central Committee (the Kopf as it is called).

The political bureau and the organising bureau meet twice a week, and the Kopf meet once a week. The latter actually considered precisely the same questions which had already been decided by the political and organising bureaus separately. If a constant connection had been established between the two bureaus by including a few members of the political bureau in the organisation bureau, then the Kopf would only have had to meet once a month for the consideration of the most important questions. In view of the construction of the Central Committee which we have described above, nothing can happen except general confusion and innumerable meetings. The apparatus of the Central Committee was no better organised. The Trade Union Department consisted of 36 people of whom more than half were responsible workers. They thought out beautiful formula, drew up theses and resolutions, and meanwhile the members of the Party withdrew from the unions.

Instead of organising Communist fractions in the unions and carrying on their work through them, the comrades in the trade union department of the Central Committee busied themselves with cabinet work. The work in the factory committees was entirely separated from the trade union work, while they dealt with essentially the same problems. The Central Committee has a department of work among civil servants, the function of which might easily have been transferred to the trade union department. Many more examples could be given of the defects in the organisational apparatus of the Central Committee of the German Communist Party, but those already given should suffice. It is to be hoped that the new Central Committee of the German Communist Party will re-organise the apparatus of the Central Committee and put into effect the scheme of organisation which the Executive Committee of the Comintern has worked out.

Tasks in the Sections in the Sphere of Organising Nuclei in the Factories and Offices.

At the Fourth Congress, Comrade Lenin pointed out in his report that the resolutions of the Third Congress on organisation had not been carried out, although they were accepted unanimously. We may state that not one of the resolutions of the Comintern Congresses on the question of organisation has been carried into effect evidently because certain sections have not considered them important, and others have not understood them.

At the meetings and conferences in Czecho-Slovakia, Germany and France, where the resolutions of the Executive Committee of the Comintern on the organisation of nuclei in the factories and shops were considered, the discussion for the most part was concerned with how to begin to put the resolution into effect, and what party rights should be conferred on the nuclei. Not one of the aforementioned meetings or conferences approached the consideration of this question from the right angle.

According to the resolution of the Executive Committee of the Comintern all members of the Communist Party must form themselves into Communist nuclei in their place of work. The nuclei consider and decide all party questions. The nuclei take in new members, and collect membership dues from members of the nuclei. The nuclei elect delegates to the district conferences, and so on. In a word, the nuclei constitute district and city organisations, because the conferences, to which the nuclei send their delegates elect the ward, district and city committees, which in their turn carry on all the party work between the ward, district and the city conferences.

The above-mentioned conferences did not understand this simple scheme. In Germany they began the re-organisation by distributing questionaries and the registration of party members in the factories and offices.

In Czecho-Slovakia, they decided to organise nuclei in the factories and offices, but the existing organisations are retained until such time as the nuclei prove their vitality. And in Paris although they have gone a little further in the sense of allowing to the nuclei of the factories and offices a large representation on the party committees, the old organisation is still retained and the nuclei have not been given the right of taking in new party members nor of collecting membership dues from their members.

Under such conditions the nuclei in the factories and shops will not take root, because all party and political questions will be considered in the parallel geographical organisations and inasmuch as in the great industrial cities of Europe and America the workers live very far from their place of work, the members of the factory and shop nuclei will try to transfer their party work to their place of residence, and everything will remain as before. However, it is more incumbent now on the Communist Parties than ever before to commence the arduous work of drawing the workers of the factories and the shops into the fight against the bourgeoisie, because the Amsterdam unions openly and cynically support the capitalists against the workers. And this work only the party nuclei can accomplish.

In our opinion, the re-organisation of the party structure must be commenced in the following manner. We will take Berlin as an example.

The Berlin committee of the Communist Party charges one of its districts to begin the organisation of factory nuclei. The latter divides the district into wards composed of all the factories in each ward. The district committee determines in which ward the work of organising nuclei will be started. One or several comrades who are familiar with the party organisation in the ward in question, are commissioned with the task of organising the nuclei. As soon as all party members who work in this particular ward are organised into nuclei, all the power which hitherto has been enjoyed by party group fractions in the ward, and which will now be disbanded, will be transferred to them. As soon as the nuclei have begun to function in one ward of a district, the organisation of nuclei in other wards of the same district must be undertaken, until the organisation of the whole district is complete. The nuclei will then elect delegates to a district conference, and the latter will elect a district committee. When the nuclei have been organised in all the districts, and the district conferences have begun to function, the latter will convene a Berlin conference, which, in its turn will elect the Berlin Party Committee.

Only by carrying out the re-organisation in this manner can there be any assurance that the nuclei will function effectively and that there will be no interruption in the work of the organisations. As soon as the ward, district and city conferences begin to function the institution of functionaries must be dissolved in all the local organisations. Certain active workers in the German Communist Party who, it seems, are not in agreement with the resolution of the Executive Committee of the Comintern on nuclei in the factories and offices, base their disagreement on the fact that “the party organisation of the Russian Communist Party is built up according to the place of residence of its members” and that “the recent party discussion in the Russian Communist Party was the clearest evidence of this, because it was conducted in the place of residence of the party members.” These comrades evidently have been misled by the fact that in the course of the discussion big meetings of secretaries of nuclei bureau considered party questions with the active workers of the district of the city. Who took part in these meetings? Mainly the members of the nuclei committees or the secretaries of the nuclei, that is to say, the meetings were convened according not to geographical, but occupational divisions; furthermore, none of the big meetings referred to above had in fact any deciding votes. All the nuclei organised on occupational lines in all the districts of, let us say, Moscow, considered and made decisions on the questions of the party discussion, and they alone elected delegates to the district conferences. The latter elected delegates to the Moscow conference, which determined the final opinion of the entire Moscow organisation on the question of the party discussion.

Organisational Problems of the Fifth Congress.

The influence of the Comintern on all its sections is enormous, but in matters of organisation its influence is negligible.

The Fifth Congress must examine the resolutions adopted by the Executive Committee of the Comintern on the organisation of factory nuclei and Communist fractions, and use its authority to bind all sections of the Comintern to execute them without fail.

Only by shifting of the centre of gravity of party work to factories and workshops and by the correct organisation of the work of the party nuclei will it be possible to draw the masses of the workers in the factories and shops into active, class conscious and organised struggle with the bourgeoisie. Only through the medium of party nuclei in the factories and shops can we organise resistance to the fascisti demagogues, who are trying to strengthen their position in the factories (in Italy, and recently in Germany, the Fascisti are organising their nuclei in the factory and shops). At the last elections of the factory committees in Germany, independent Fascist tickets were put up. The Fascisti say openly that the power of the trade unions in Germany has been destroyed, and that, therefore, the Fascisti must fortify themselves in the factories. Unfortunately, there are some active workers in the German Communist Party who still fail to understand the great importance of the organisation of nuclei in the factories and shops.

The organisation commission at the Congress must work out a uniform system of organisation of both the central and the local party organs to the Comintern sections.

Immediately after the Congress the Organisation Department of the Executive Committee of the Comintern should be reinforced by the addition of workers from the strongest Comintern sections.

The organisation department must receive full power from the Executive Committee to control the execution of all the resolutions on organisation passed by the Congress and the Executive Committee.

The Organisation Department should be given the right to send organisers to the different sections, both to the central and the local organisations (local organisations of national sections) to give instructions on the execution of the decisions of the Comintern, and to check up the extent to which these decisions are practically adaptable.

Both the Congress and the Executive Committee should apply themselves to the organisational problems of the sections with the greatest energy and determination.

Only after the Comintern sections have reconstructed their party organisation in accordance with the resolutions of the congress and the Executive Committee will the Communist Party be able to bring the party organisation into closer contact with the working masses, and to attract all the members of the party into active participation in party work and in decisions on all questions of party life.

And only when the whole party from top to bottom joins in the active execution of all the decisions of the party in all institutions, factories and offices, and in all organisations where workers are to be found, will the Comintern sections be able organisationally to consolidate the enormous influence they wield over the working class and over the poor peasants.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n04-jul-aug-1924-new-series-CI-grn-riaz-orig-cov-r2.pdf