A valuable, detailed, and perceptive analysis from Droz on the complicated conditions of Belgium’s Communist movement of the 1920s. Humbert-Droz, the veteran Swiss Marxist was a founder of the Third International imprisoned in Switzerland during the War for his anti-war activities despite that country’s professed neutrality. That neutrality meant the country was a refuge for many exiles during the First World War, giving Droz connections from across the continent. After the Russian Revolution, Droz relocated to Moscow where his contacts made him a Comintern representative to Western Europe where he would be involved in stabilizing the Belgium Communist movement. Specific issues confronting the C.P. in that country included its relatively small numbers; the country’s national linguistic, religious, and national divide; Belgium’s very unfortunate, and dangerous, geography between Europe’s most destructive rivalry; the strength of a conservative Socialist Democracy within the workers’ movement and national politics; Belgium’s almost total financial dependence on exploitation of its colonial possessions; and the formidable strength of the Left Opposition, perhaps a majority, in the Party and its leadership. A supporter of Bukharin’s, Droz would eventually be, with finality, expelled from the Communist in 1943, to find his way back to the Belgium Social Democracy which he would serve as Party Secretary until 1958.

‘The Communist Party of Belgium’ by Jules Humbert-Droz from Communist International. Vol. 3 No. 4. October 15. 1926.

BELGIUM is one of the most formidable strongholds of Social Democracy. The Belgian Labour Party (P.O.B.) with its trade unions, Co-operatives, mutual aid societies and “Palaces of Labour,” very powerful organisation not only because of its numerical strength–650,000–but especially because of its close contact with the proletarian masses. In the whole Second International there is no Party more steeped in the ideas of reformism. The policy of the “sacred union” (Union Sacrée) which it followed during the world war has been maintained since the war ended.

A few small advantages, ephemeral and frequently illusory, which the P.O.B. has been able to secure for the workers by participation in the government and which its vast bureaucratic apparatus has cleverly exploited in order to dope the workers, has made possible a cynical betrayal of the interests of the proletariat which has not as yet resulted in the alienation of the masses.

In face of this colossus the small Communist Party of Belgium–800 members–seems feeble indeed; and the development of Communism in Belgium would appear to be an arduous and difficult task. The Communist Party of Belgium is confronted not only by the formidable trade union, co-operative and political organisation of the P.O.B.; it has also to contend with a feeling of unity firmly embedded in the mentality of the Belgian youth.

The small group which emerged from the P.O.B. to form the Communist Party seemed to be disrupters, secessionists from the Labour movement. For many years the feeling for unity which permeates the toiling masses, strengthened in Belgium by the organisational tradition of the P.O.B., has been one of the greatest obstacles to the development of our Party. Even today the P.O.B. is carrying on a bitter struggle against the Communist Party on this ground.

The Communist Party of Belgium has not escaped the perils of errors which arise from its position of extreme numerical weakness. For a long time it was imbued with the sectarian spirit, concentrating its attention and main efforts on the education of its few hundred members, on propaganda and agitation, without making an attempt to organise the influence gained, to recruit new members or even to utilising all its members for its work and campaigns.

However, in spite of its numerical weakness and its errors, which it is trying to make good, the Communist Party of Belgium exercises an influence which is out of all proportion to its small numbers, an influence which is steadily growing. This small Party of 800 members polled 34,000 votes during the parliamentary elections, on April 5, 1925, in those districts where it put up candidates. In the municipal elections on October 10, 1926, it polled 70,000 votes in the 64 districts where it put up a fight, a smaller area than that of the parliamentary elections.

Municipal elections offer a much less favourable ground for a Communist campaign than parliamentary elections, because local and often personal questions play a preponderating role; these figures therefore show that the Communist Party of Belgium has succeeded in gaining an influence which is rapidly spreading. Moreover the fact that the P.O.B. went in for polemics against the Communists during these last elections shows that the P.O.B. is fully aware of the effect of Communist propaganda and is beginning to think that its own influence over the masses may be impaired by it.

Expelling Communists

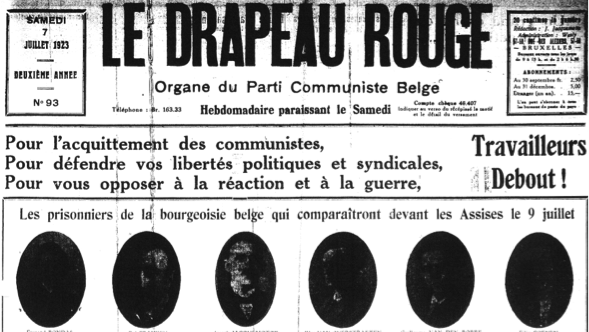

The growing influence of the Communist Party of Belgium is not limited to election times. It finds expression in the 6,000 readers of the “Drapeau Rouge,” the daily organ of the Party, and its growing influence within the trade union movement, the effect of which is to develop a Left Wing which stands for trade union unity.

The reformist leaders have done their utmost to isolate the Communists from the workers organised in the trade unions. The “Mertens” motion to expel Communists from the unions, adopted by the Trade Union Congress, introduced into Belgium the Amsterdam splitting tactics. But although the Party is numerically weak, the reformist leaders who are trying to put into force the “Mertens” resolution are meeting with considerable hostility on the part of trade unionists to whom the unity of their organisation is sacred. This devotion to unity, which used to be an obstacle to the development of the Communist Party, is today telling against the reformists and to the advantage of the Communists who defend trade union unity.

Only recently, on October 2nd, 1926, the National Congress of the Union of Clerks rejected by 3,912 votes against 1,272 the proposal to expel our comrade Jacquemotte.

The “Unity” Left Wing is not a Communist movement. On certain questions there are serious differences of opinion between our Party and the “Unité” group, as well as between our Party and the “Left Wingers of the P.O.B. But the development of a trade union Left Wing and the existence of a Left Wing within the P.O.B. weaken considerably the reformist offensive against our Party, and are instrumental in making important sections of workers veer to the Left. It is now the duty of our Party to get these Left elements under our influence and to attach them to our Party.

Our Party has been able to gain in influence because of the political situation, which is very favourable to the development of Communism among the Belgian workers.

Belgian proletarians “have been enjoying” for more than ten years all the beauties and benefits of reformism and of class collaboration. Every day they can see its effects–bread is black and very dear, wages are less and less able to keep pace with rising prices, strikes and movements to enforce the workers’ demands are inevitably betrayed by the trade union bureaucrats.

Vandervelde in Power

The Social Democrats have been in power since the April 1925 elections, the main characteristic of which was the veering to the Left of large sections of workers, petty bourgeois elements and peasants, who were dissatisfied with the inflationist and anti-Labour policy of the Catholic Conservative Government. The P.O.B., which is allied to the Christian Democrats in the Government, has shown itself unable to resist the policy of the financiers and industrialists. After pursuing a policy of inflation and depreciation of the franc (which resulted in high prices, a reduction in the real wage of the workers and a pauperisation of the petty bourgeoisie) and failing in their first attempt to stabilise the franc at the expense of the workers, the Social Democrats reestablished “for the defence of the franc” the sacred union with the Catholic Conservatives and Liberals whom they had defeated in 1925; this they did at the bidding of the bankers against whom they had promised to fight.

They approved and defended before the masses the measures which the bourgeoisie is endeavouring to use in order to place the burden of the stabilisation of the franc on to the shoulders of the workers; the heavy indirect taxes, the handing over of the State railways and other public services to private capital, etc. All the efforts of the workers to get a rise in wages meet with resistance on the part of the industrialists and are sabotaged by their lackeys, the reformist leaders.

Although the Social Democrats have used all their skill to make their treacheries to the workers look like successes for the working class, the masses are beginning to see and to feel that they are the victims of a colossal fraud and that the P.O.B. has allied itself with their enemies. Thus the political situation is propitious for the propaganda and agitation of our Party.

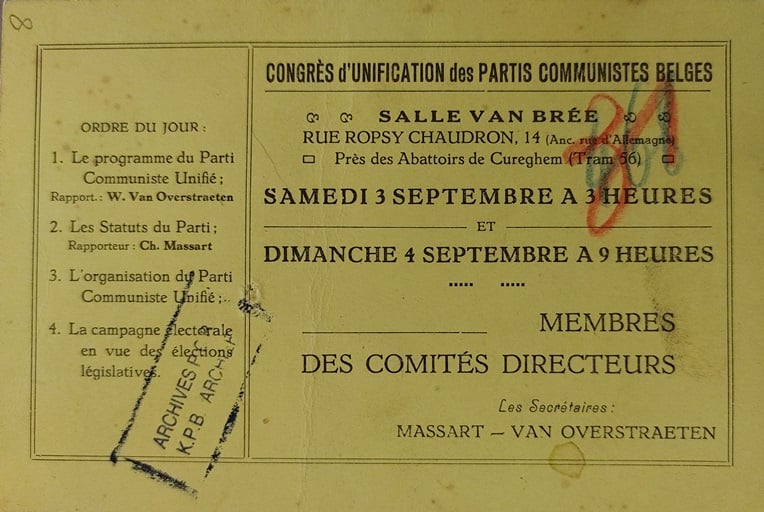

These are the circumstances under which the Fourth Congress of the Communist Party of Belgium was held at the beginning of September.

The Party Congress

In its political report the Executive Committee of the Party, after an analysis of the political and economic situation of the country, submitted the entire activity of the Party to a fair and thorough searching self-criticism, exposing its weaknesses and errors, its inadequate political leadership in the face of everyday tasks and the growing influence of the Party, the absence of any organisation capable of establishing contact between sympathisers and Communist electors and the Party, the perilous disproportion between the numerical strength of the Party and its influence on the masses and the failure to utilise all the forces of the Party for political and trade union activity.

Apart from these serious questions of organisation, on which the development of the Party depends, the Congress had to elucidate various important questions, first and foremost that of trade union tactics–its relations with the “Unité” group, its attitude towards expulsions, towards the “Knights of Labour” (“Chevaliers du Travail”) and its attitude to Fascism and to the anti-Fascist defence corps of the P.O.B., its tactics in the national question with regard to the Flemish movement, and its attitude towards the “Left Wing” of the P.O.B., etc.

Did the Congress give a clear answer to these questions, and clear directions to the Party? Did it approach these tasks in a concrete and practical manner?

The answer must be an emphatic “No!”

In spite of the fact that the political report pointed out the weaknesses of the Party and that the letter addressed by the Presidium to the International very forcibly indicated which problems ought to be the centres of attention at the Congress, two days were spent in petty criticisms of a purely negative character without any effort being made to find practical solutions for the tasks before the Party.

Nothing Done!

The political report with its excellent self-criticism was adopted, but not a single measure was taken to remedy the errors ! The trade union report was not even discussed; organisational questions, so important in the present situation, were postponed until a later conference. The balance-sheet of this Congress is decidedly unsatisfactory.

Moreover a number of speakers proved that sectarianism was not dead in the Party. The only remedy advocated by them was to educate the 800 members of the Party; a very necessary task at any time, but one which at the present juncture is certainly not the most essential task, not the task on which all the efforts and all the work of the Party should be concentrated.

While the result of the municipal elections is another important victory for the Party, it at the same time points to the risk the Party is running if the questions raised at the Congress, and left unsolved by it are not tackled energetically and in a practical manner without further delay. The Party has 70,000 followers who voted for it in 64 constituencies. These electors are workers disillusioned with the Social Democrats, and influenced by our widespread and efficient agitation. But the Party does not know who these thousands of sympathisers are!

Our campaigns have detached them from the formidable Social Democratic tradition, but only one per cent. of them are organised in our Party; 10 per cent. are occasional readers of our press; the Party has no contact whatever with the other 90 per cent. It does not know where to find them except at election time, and cannot therefore utilise them for its mass movements, its trade union work, and its campaigns for the capture of new and important sections of the working class.

If for demagogic purposes the P.O.B. were to come out again in the role of the Opposition in Parliament, the masses, over which we have no control whatever and with which we have no organic links, will probably go back to the Social Democrats. During the election campaign Vandervelde made it perfectly clear that the P.O.B. did not intend to uphold the coalition Government after the franc had been stabilised, and this is being hurriedly put through. The result of these municipal elections will no doubt finally convince the reformist leaders that it is essential for them to be in opposition unless they want to give up their influence over the masses to Communism.

Recruits Needed

Therefore we must be prepared for a change of front by the P.O.B, and for a big demagogic campaign when it dissociates itself from the coalition Government after the stabilisation of the franc. What will then be left of our whole agitation, if the Communist Party does not consolidate the breach which it has just made in the stronghold of the Social Democrats, it if does not organise its influence over the electors?

The essential task today is not the education of the 800 members of the Communist Party, it is rather a big recruiting campaign to secure new members for the Party, a big effort to double and treble the number of subscribers and readers of the “Drapeau Rouge” by improving it and converting it into a real daily organ of the workers.

We are aware that the organisational tradition of the Belgian proletariat is not favourable to individual recruitment. The workers are affiliated to the P.O.B. through the collective affiliation of their trade union, their co-operative, or their mutual aid society. But to make this an argument against an effort to recruit and organise new members is to lull to sleep the activity of the Party, to shield the relics of sectarianism and the slackness of the apparatus of the Party. Agitation and propaganda become a peril whenever their success is not followed by efforts to carry on methodical organisation.

What the Party Wants

On the other hand it goes without saying that although the tradition of collective organisation that exists in the P.O.B. is an obstacle to individual recruiting, it is certainly not an obstacle to the distribution of Party publications. The Party must try to find means to get in contact with the masses, which are meeting it half way. This very important question, which the Congress left unsolved, is becoming every day more important and more imperative; it gives rise to a series of other questions just as urgent–the need for a real collective leadership of the Party, making possible a more methodical and consistent political activity, for a complete reconstruction of the inadequate organisational apparatus and the formation of an organisational commission or section, for the improvement of the editorial part of the Party’s newspaper and closer contact between it and the Party lead, for close collaboration between agitational and organisational activities, for the utilization of all forces of the Party and the enlistment of new members for political and trade union work, and finally the need for a solution of our trade union questions and of the question of how to use Communist electors in trade union work.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-3/v03-n04-nov-30-1926-CI-grn-riaz.pdf