U.S. Communists debate imperialism and the United States Empire as part of a larger exchange on the topic of colonialism at the Comintern’s Sixth World Congress in 1928. Sam Darcy speaks on specific youth and Young Communist aspects; the long, still valuable divide between Charles Phillips (Manuel Gomez) and Bertram Wolfe—the two leading U.S. comrades involved in ‘Latin American’ affairs at the time—over both practical policy and differences over the very nature of U.S. imperialism and it effects is engaged, mirroring the intractable Foster-Lovestone factional schism at home. Important also were the speeches of Black delegates James W. Ford, wearing his Profintern hat, and Otto Hall (‘Jones,’ older brother of Harry Haywood), relating the struggle against imperialism to the struggle for Black freedom in the United States, a signal of a real shift in orientation to Black liberation on the part of the U.S. Party. Lenin’s thesis on the National and Colonial Question at the Communist International’s Second Congress in 1921 was the cornerstone and most important anti-imperialist statement of the Comintern. These discussions around the Sixth World Congress in 1928 were the other outstanding moment, and one I hope to transcribe them entirely here. By the mid-1920s, the Comintern had ‘faced East’ out of both its genuine commitment to the growing liberation struggles of the East (broadly defined), and as a necessary act of survival after mid-1920’s retreats, defeats, and bloody routes; the calamity of a victorious fascism. As a result, 1928’s Congress for the first time heard voices of delegations from much of the colonial and neo-colonial world, representing most of humanity, and the majority of the world’s proletariat. As the most powerful, though still emerging, imperialist power, the interventions of U.S. delegates deserve attention, especially by current U.S. activists. They are, understandably, mainly concerned with Central and South America. The interventions recorded below are framed by the associated World Congress’ document and discussion: ‘Theses on the Revolutionary Movement in the Colonies and Semi-Colonies,’ the report ‘Questions of the Revolutionary Movement in Latin American Countries’ by Jules Humbert-Droz, with the substantial intervention from over a dozen, Central and South American delegates ‘Communism and Anti-Imperialism in Latin America’, and could well be read together.

‘U.S. Communists on Imperialism and the United States Empire’ from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 8 Nos. 74, 76, & 78. October 25, 30, & November 2, 1928.

Comrade DARCY (Young Communist International):

Comrades, in the main I agree with the theses; there are, however, a few remarks that I would like to make on some of the questions.

I believe the theses do not deal sufficiently concretely with the situation in Latin America. Prior to the war, Great Britain had investments in Latin America totaling about 5000 million dollars, while the United States had investments in Latin America totaling about 1000 million dollars. Now, however, while the investments of Great Britain have remained stagnant, United States investments have increased to five thousand, two hundred million dollars. The rivalry between the United States and Great Britain has been ever-increasing and becoming keener. It is in this connection that I think the theses have a shortcoming. They treat the role of the bourgeoisie, especially the industrial bourgeoisie in Latin America, just as the bourgeoisie in such colonies where the imperialist country has a monopoly on the exploitation of that colony. In some Latin American semi-colonies there is a tendency among the bourgeoisie to play a less revolutionary role, because the native industrial bourgeoisie is making alliances with one or the other of the imperialisms (England or America) in order to further its own ends. As a result it hampers the struggle of the masses and becomes dependent upon imperialism in order to obtain concessions from it.

In the four groups of colonies enumerated in the theses the Latin American countries are only mentioned in the first group. This gives a false impression. Both as regards the political and economic development Latin America is not a single unit in which all its countries have economically reached the same point of development. But on the contrary we have very many types of colonies represented, such as the so-called A.B.C. countries, Argentine, Brazil and Chile. We have a number of countries which have hardly any industrial development at all, in which there still exist semi-feudal relations. We have colonies where the landlords are the strongest factor. In Mexico we have what we can call a crystallising centre for all Latin American struggles against imperialism, and its role is therefore a much greater one than any of the other countries in Latin America.

This and other questions must be dealt with more in detail in the theses and the approach of the Comintern and of the Parties in the colonies and in the imperialist countries worked out.

A few words about the work of the Party and the League in the United States in relation to the colonial question. The theses do not deal at all with the tasks, nor do they estimate the work of the parties in the imperialist country in the colonial question. The American Party, thanks to the experiences of the other parties of the Comintern and having regard to the situation in Latin America, developed a number of general and concrete slogans with which it had carried on its work. One comrade, who spoke in the discussion, said that the American Party has neglected the struggle in Latin America. This is not true. It is true that considering the greatness of the task, the forces at the disposal of the American Party for this work are insufficient and must be strengthened if the proper amount of work is to be carried on. It is also true that errors have been made, that the best comrades were not charged with this work, and that the achievements are small compared with what is needed. However, on the other hand, we must say that the work of the American Party and League has been far in excess of what it has ever done before in this connection, and that both the American Party and the League have taken advantage of the situation in Latin America in order to carry on the struggle, by popularising the colonial struggle among the workers of the United States under such slogans as “Defeat the Nicaraguan Intervention”, “Desert to Sandino”, etc.; such slogans as “The abolition of Financial Supervision by America”, “Withdrawal Troops”, etc.

The campaign of the American Party was carried out largely by the following methods: 1. demonstrations, mass meetings, etc., of a general character; 2. demonstrations in front of the navy yards and soldiers barracks, etc., with slogans denouncing and calling for the defeat of the many attempts of American Imperialism in Latin America; 3. The distribution of leaflets to soldiers and marines just prior to their leaving for Latin America and China; 4. Of the establishing of contact with some of the colonies, through the sending of comrades into some of the colonies for organisational work for the league and Party, 5. of course, all our anti-militarist work was centered around support of the colonial struggles.

What are the present tasks of the American League and Party and also of the Y.C.I. in this connection? First, I think we must try and establish a Young Communist League in every colony in Latin America, as now there exist only a few. I think we must strengthen the connections between the revolutionary forces in the colonies and the proletariat at home. We must bring delegations from the colonies and tour them throughout the United States and every imperialist country in order to popularise the cause of the revolution in the colonial countries and to bring it more graphically before the eyes of the proletariat at home. I think we must strengthen our propaganda among the colonial troops. I think that both the Comintern and the Y.C.I. must devote more attention to the problem, especially to the Latin American countries than has been done hitherto.

In this connection I must support the statement of Comrade Banderas when he said that it is a mistake to have the Latin American question dealt with by the Latin Secretariat of the Comintern and the Y.C.I. This question belongs politically in an all-American Secretariat, and the only connection it has with the other Latin countries, such as Italy, are language connections and not political connections. The Y.C.I. has made a big step forward in this connection when it organised for the World Congress of the youth, a special all-American conference in order to deal with the problems of the common struggle of the American Party, the League and the colonial youth against American Imperialism.

In the theses there is no mention of the problems of the colonial youth. Still the work among the youth in the colonies, cannot be only the task of the revolutionary colonial youth movement, but is also a task of the Parties. Such organisations as the Y.M.C.A., the student organisations of a reactionary character, the religions organisations which exist in the colonies, point to the tremendous problems that face us, and to the importance of setting up in all colonies revolutionary mass Communist youth organisations which in most cases do not yet exist. Despite the importance of this problem, during the past year or two doubts have arisen as to the possibility of developing young Communist Leagues in the colonies into mass organisations.

I have no time to go into the merits of the question itself, but I must indicate that our experience in such colonies and semi-colonies as China, Mexico, have proven that it is possible to build up a mass Communist Youth League. In Mexico our Young Communist League is larger in membership even than our Party. But this problem does not only concern the youth but also the Parties. It is therefore incumbent upon the theses to deal with this problem and to give an answer to it.

There has developed in various countries, especially in China and the other colonies, both in the Party and in the Communist youth movement, tendencies which deviate from our course and have become and in the future can become dangerous. On the one hand proposals for the liquidation of the youth movement have come forth based on the conception that because the percentage of youth in the working class is very large, the problems of the youth become the problems of the whole working class and we therefore do not need a youth movement. And on the other hand, owing to the weakness of some Communist Parties, the youth have developed tendencies towards vanguardism. The Comintern and the Y.C.I. have dealt energetically with both the deviations as soon as they arose but I believe that now in the theses of the World Congress we must put this question clearly for the future, to make the road free for the development of Communist Youth Movements. Especially must we include it in the theses because these deviations are found also in the Parties.

In conclusion, I would like to say that the main tasks confronting us on the colonial question are not only in the colonies themselves, but also among the proletariat in the imperialist countries. The theses should set as one of the main tasks of the Communist International the close connection both organisationally and politically of the struggles of the colonial peoples with the struggles of the proletariat at home. It is true that we are already connected through the Comintern, but I think that apart from this we must also connect the Parties and masses directly, so that the struggles on specific issues and in specific situations can be carried out more effectively against imperialism.

Comrade MANUEL GOMEZ (U.S.A.):

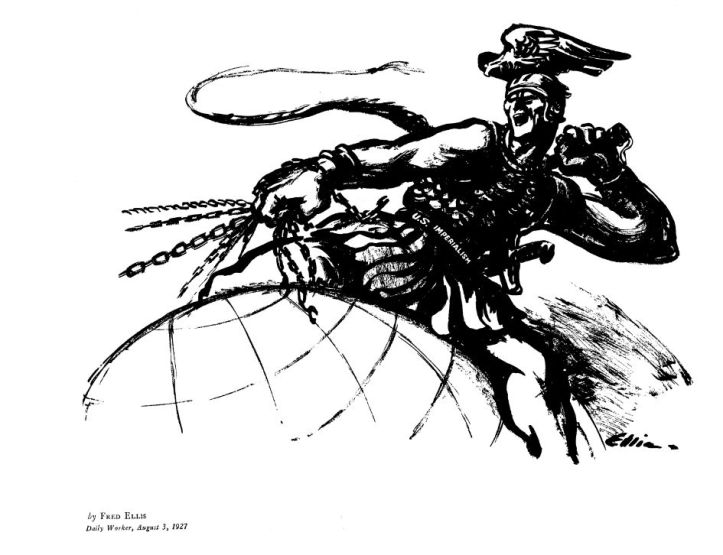

The guiding principle governing our approach to the colonial question is the essential unity between the revolutionary movements in the oppressed countries and the process of the proletarian world revolution. I wish to say a few words on the struggle against American Imperialism, from the standpoint of general strategy on an empire scale.

This requires first of all an understanding of the world role of American Imperialism, of its striving toward world hegemony and of the central feature of its policy, which is that it is a war policy. At the time of the Nanking Massacre the majority of our Party’s political committee based its activities on the theory that the United States was Great Britain’s “catspaw” in China; and only a few months ago (in its statements on the Tsinan incident) it declared that the United States was the tail-end to Japanese imperialism! These comrades picture American imperialism in the Far East as playing no independent aggressive role, being used now by British, now by Japanese imperialism, for their own brutal ends. Comrade Wolfe defended the “catspaw theory” before our Party plenum on the ground that the United States is still guided primarily by the old democratic-pacifist Open Door policy in China. He quoted statistics to show that American capitalism had very little capital invested in China and was interested in China only as a market for commodities. Comrade Wolfe and Comrade Lovestone refuse to see that in the present period even the question of markets is bound up with monopoly policy and domination of market areas.

British and American imperialism are the outstanding antagonists of the capitalist world. Antagonism between American and Japanese imperialism is no less sharp. Under these circumstances to indulge in such burlesque explanations of U.S. policy as our Polcom majority has done means not only to confuse the workers, not only to shirk the direct campaign against American imperialism, but might even help to create a receptive attitude among some workers for chauvinist ideas.

Within a few hundred miles from Canton are the Philippine Islands, America’s largest colony. The dominant party in the Philippines is the so-called Nationalist Party which represents the thoroughly corrupted national bourgeoisie. It disguises its betrayal of the struggle for Philippine independence by empty appeals for favours from Washington. The task in the Philippines is to build a new, revolutionary, movement based upon the masses of workers and poor peasants; to orientate it away from appeals to Washington and towards contact with the revolutionary movement in China, as well as with the Indonesian movement. The first task, however, is the formation of a Communist cadre. The American Party must send representatives to the Philippine Islands for this work without further loss of time. Absolutely no effort has been made by our Political Committee to do this, despite specific instructions from the Comintern.

The strategy of the struggle against American imperialism is obliged to concern itself most particularly with the problem of destroying the primary base of American imperialism, Latin America, and of converting it into a base against imperialism.

The anti-imperialist struggle in Latin America will go forward under the slogan of the United Latin-American anti-imperialist front. It would be ridiculous to believe that Latin-American unity is possible in the sense of a federation of the existing states. Nevertheless, we must issue the slogan of a union of Latin-American countries against imperialism, and we must denounce bourgeois opposition to unity as sabotage of the anti-imperialist united front.

Comrade Banderas does not like all this “Latin-Americanism”. He is afraid: 1. that the petty bourgeoisie may make use of it to dominate the movement; 2. that it may make the Latin-American masses turn away from the idea of unity with the workers in the United States. Well, I have no such fears. Comrade Banderas will not find the Latin-American petty bourgeoisie so willing to fight for the union of the Latin-American countries and neither will he find the revolutionary elements in Latin America so antagonistic to alliance with the class-conscious workers in the United States. They will, and do, look with hostility upon the bureaucracy of the American Federation of Labour, but that is quite another matter. By all means unity between the Latin American movement and the revolutionary proletariat in the U.S. Nevertheless it was correct for the Profintern to approve the launching of a Latin-American Federation of Labour.

Comrade Humbert Droz has indicated the general relation of class forces in the revolutionary movements throughout Latin America. We must be able to find the point of intersection of all these diverse movements, which differ widely from country to country, and unite them in a common movement under our leadership, together with the revolutionary proletarian movement in the United States. The form of the All-America Anti-Imperialist League is well suited to this purpose. Other subsidiary unifying forms for the struggle on a continental scale must also be developed.

Considering further the question of strategy in Latin America we must bear in mind the special position of the Caribbean area. We should send special forces into this region. Above all we should make it possible for the Mexican comrades to directly assist the development of Communist cadres there.

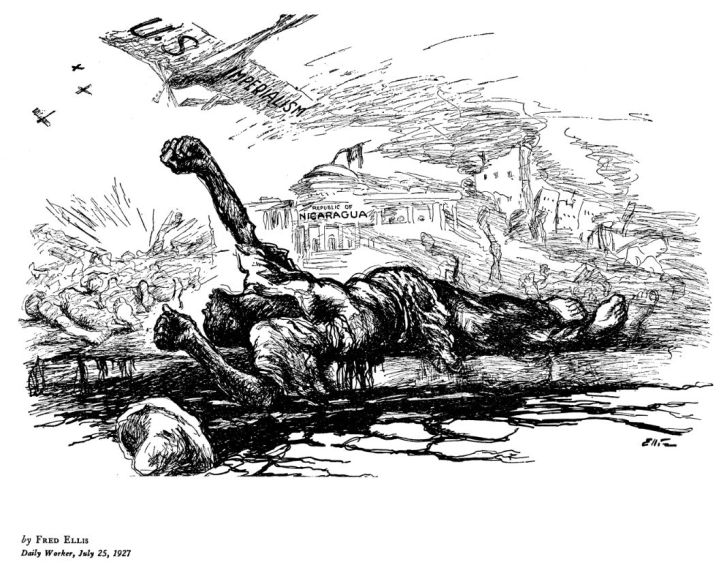

The war of American imperialism in Nicaragua is expressive of the whole aggressive drive of American imperialism against Latin America. In all Latin American countries support to the Nicaraguan struggle must be the focus of our anti-imperialist campaign. In the five countries making up the historical Central American nation (whose unity has been repeatedly thwarted by the manoeuvres of American imperialism) the war against Nicaragua must be denounced as a final blow at Central American national unity.

Speaking of Mexico I agree with Comrade Banderas that the Mexican Revolution cannot be regarded as having ended, notwithstanding the desertion of the bourgeoisie, so long as the agrarian revolution is incomplete, and large numbers of peasants are armed. Comrade Humbert Droz stated that our Mexican comrades made mistakes in the past with regard to their attitude towards the Mexican government. I wish to point out that since the murder of Obregon there are signs of a recurrence of the these mistakes, in a totally changed situation which would make them far more dangerous.

Many reasons combine to make Mexico the traditional territorial centre of Latin American resistance to American imperialism, and it is in Mexico that the centre of our anti-imperialist movement throughout the Americas must be established. The present centre should be strengthened with the help of the Comintern along the lines of a proposal which is being submitted.

Before concluding I wish to set down the points of strategy for the work of our own Party in the United States, as follows:

1. Draw American workers into the general anti-imperialist struggle through, and in connection with, the struggle against the War Danger.

2. Win the semi-awakened masses away from pacifist leadership through pitiless exposure of pacifism and the Pacifists and Socialists as a prop of capitalist state power and war preparations.

3. Lead American workers along the line of active cooperation with the colonial and semi-colonial masses on the basis of the international ramifications of trustified American capitalism and the day-to-day requirements of the proletarian class struggle against it.

4. Link up the struggle of the Negroes as an oppressed minority in the United States with anti-imperialist struggles in Haiti, Santo Domingo, etc. This includes propagation of the right of self-determination for the Negroes in the United States.

5. Combine work in the military and naval forces with the activities among the broad masses.

6. Draw in non-proletarian elements (farmers and urban petty bourgeoisie) as allies in the workers’ anti-imperialist movement under our influence.

7. Establish close contact with the Latin-Americans, Filipinos, Chinese, etc., in the United States, on the basis of their interests as especially oppressed workers in the U.S. as well as on the basis of the struggle in their home countries.

Our Party has been criticised here for inactivity with regard to the Nicaraguan war and for insufficient anti-imperialist work generally. This criticism is fully justified. The roots of this lie very deep and are connected with the same circumstances as those responsible for the Party’s failure to do any serious work among Negroes. Everything accomplished has been without the support and against the resistance of the majority of the Political Committee. The Lovestone Group has attempted to maintain here that the Party would have done excellent anti-imperialist work if it were only not for the head of the anti-imperialist department. And yet they do not cite one wrong policy of ours. All they are able to find is a single isolated slogan, out of the hundreds of wrong slogans that our Party has put forward in its various fields of activity. Comrade Wolfe has repeated here the charge that there was created a special petty-bourgeois Red Cross organisation in the Nicaraguan campaign. This is an absolute lie, as every member of our Political Committee knows.

The truth is that the majority of our Political Committee underestimates anti-imperialist work, underestimates Negro work, underestimates our responsibility to the colonial and semi-colonial movements, underestimates the War Danger. The Lovestone group members do not attend meetings of the anti-imperialist committee. Anti-imperialist work has not even been made a point on the agenda at a single Party convention or Party plenum since the Lovestone Group came to power. Comrade Lovestone has had the nerve to boast of anti-militarist work, when the Party did not send a single man to work among the troops in Nicaragua, or in China either.

Can we organise an empire-wide strategy for the struggle against American imperialism? Only if our Party in the United States understands that it must show the way.

Comrade FORD (Negro Comrade from the U.S.A.) in name of the Communist Fraction of the R.I.L.U.:

Comrades, permit me to speak first on the attitude of the Socialist Party, the II. International, to Negro and colonial peoples in general; secondly, on some theoretical points in connection with the Negro question in America; and thirdly, on some practical steps towards carrying out our general programme.

First, a protest was recently made by colonial guests at the Congress of the II. International at Brussels, the essence of which characterises the attitude of the II. International to oppressed peoples in general and also to the Negro peoples in particular. This protest reads as follows:

“Having examined the decisions of the colonial commission of the Socialist Labour International, we have arrived at the conclusion that these decisions, in their present form, are inconsistent with the equality of nations and with the principle of self-determination, and equality of peoples should be applied to all oppressed nations and subject races without any distinction whatever.”

This protest brings out the basic principles of the II. International with regard to the oppressed peoples, and particularly to Negro peoples which is characterised by the following quotation:

“This point of view is held by such renegades as Kautsky, who maintains that the whole racial question amounts exclusively to the class struggle between the proletariat and

the bourgeoisie, and that there is no need for any struggle for the social equality of the oppressed races and that such a struggle is even harmful since it interferes with the fundamental struggle. Let the Negroes wait until the advent of socialism, then the emancipated proletariat will proceed to emancipate all the oppressed peoples including the Negro race in America.”

Let me now examine the attitude of the II. International in regard to the Negroes in America. In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, a progressive Labour League made up of Negro workers recently called a conference to participate in the elections in Milwaukee. This conference, which included fraternal organisations, working class organisations, sent also an invitation to the Socialist Party of Milwaukee. The Socialist Party refused to participate in this conference upon the ground that the movement was essentially a race movement, and not a working class movement. In an article appearing in the “Ford”, an organ of the Socialist Party. of America, Mr. Bruce, in analysing the Negro situation in America, states the following:

“But it is true as the years pass, as more and more Negroes come to the North and become decent, self-respecting men and women, doing their work, exercising their citizenship like their fellow Americans, the Negro problem will tend more and more to be solved.”

This also characterises the attitude of the Socialist Party in regard to the Negroes in America, which is entirely an un-socialist point of view.

The election platform of the Socialist Party in America at present says in regard to the Negro question:

“The Convention records its sympathy and support of the Negro workers to wipe out the discrimination against which they have unremittingly laboured since the end of the civil war. The Socialist Party favours the Federal Anti-Lynching Bill, and is against the continuance of Negro lynching in some of the States and the heartless policy of Jim Crowism’.”

This policy represents the same standpoint as adopted by the two bourgeois parties of America, the Republican Party and the Democratic Party. It also supports, as it says in its platform, the Negro porters who have been organised to the extent of 12,000. But again in reference to the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a Negro trade union organisation which is entirely under the influence of the Socialist Party, this organisation has been allowed to slip into the hands of the reactionary A.F. of L. and at the last moment of their strike, Mr. Green of the A.F. of L., was allowed to call this strike off in the name of “seeking justice before the American Public for this strike.” In this case there is a complete betrayal of the interests of 12,000 Negro workers who are labouring under the worst conditions of exploitation by one of the richest corporations in America.

Recently in the United States, in the name of “fair play”, “freedom of speech” and “freedom of the air”, the Socialist Party of America allowed an agent of the American imperialists to broadcast over their radio station (a station which has been built in the memory of Eugene V. Debs) a defence of American imperialism’s encroachment upon the defenceless Nicaraguan people.

The II. International has divided the colonial peoples into four categories according to their degree of development. It says in reference to the first group, while we will stand for a partial principle of self-determination, we will not stand for complete freedom. To the other three groups, well, we will not agree to any separation from the mother country, you are not quite fully developed and so forth, and so on. Finally, this characterisation of the attitude of this bunch of social imperialists towards oppressed peoples can be summarised in the following point of view of Kautsky:

“This problem of social inequality is reduced to the national and colonial peoples.”

In this sense he speaks in his “Judaism and Race” when he refers to the great gulf between the civilised and backward races and that the only road for the workers is to go on driving for independence and to assimilate the achievements of civilisation of the white peoples.

However, comrades, in pointing out this fundamentally incorrect principle on the part of the II. International, and the Socialist Party, of downright collaboration with the imperialists, we must not overlook in our own ranks, certain deviations in regard to our attitude toward Negro peoples. In Milwaukee there was a slight deviation on the part of certain elements in our Party not to co-operate with the movement of the Negroes there. But this deviation will be eliminated.

But the attitude of the II. International is a matter of principle. The Negro peoples and colonial peoples cannot accept the policies of the II. International. The colonial peoples and Negro peoples can and must accept only the leadership of the Communist, the III. International as its leader against imperialism. There is a considerable discussion going on in the Negro Commission regarding the slogan for a republic of the Negro peoples in America. The Congress must give this question very serious attention indeed. It is necessary to examine thoroughly some of the following points of view. 1. What are the economic roots of international antagonisms? 2. What are the class contradictions within the dominating nations? 3. What are the sources and character of national chauvinism? 4. What is the basis of the national ideology of an oppressed nation or group and the effect of class differentiations, as well as what is the course of national emancipation movements?

The economic roots of national antagonisms as applied to the Negroes in the United States rise from the following propositions: that the Negro is an economically backward national minority which has no territory.

Here the question is the extraction of not only colonial super-profits, but the extraction of super-profits of the colonial peoples outside the confines of the imperialist nations. In the budding or emerging stage of capitalism we can conceive that the interests of the proletariat and the bourgeoisie for self-determination are coinciding or moving along the same lines for political and economic independence and even for a time, further, for cultural and language freedom, etc. Yet there is the ever-growing antagonism between the oppressed proletariat and the bourgeoisie which causes the collapse of nationalist unity.

At this point of development of the proletariat the bourgeoisie begins first the disintegration of the proletariat by arousing national chauvinism and secondly, by bribing the upper strata of the proletariat and petty bourgeoisie. Therefore, there can be no common national ideology of the oppressed proletariat and the bourgeoisie.

The ideology of nationalism on the part of an oppressed group is based upon the national ideology of the oppressed nation as the ideology of all its classes. This ideology is developed by the fact that they constitute a nation, or that they are living in one territory, under the same conditions and the same economic development, using the same language, etc., and 2. by the fact that they are oppressed and exploited by another nation which is technically more developed and through which their economic development is artificially retarded, that they cannot attain political independence, etc. In all cases of national antagonism the basis is the difference of technical and economic development.

In the United States we find no economic system separating the two races. The interests of the Negro and white workers are the same. The Negro peasant and the white peasant interests are the same. But the bourgeoisie has set up a racial barrier, playing upon the differences of colour, of skin and so forth, in order to super-exploit the coloured workers, which has its effect, to a great extent, upon the white workers.

It seems that any nationalist movement on the part of the Negroes does nothing but play into the hands of the bourgeoisie by arresting the revolutionary class movement of the Negro masses and further widening the gulf between the white and similar oppressed groups.

The revolutionary movement of the Negroes can take three forms: 1. the Negro movement may manifest itself as a reformist movement, of the opportunistic, conciliatory upper strata of the Negro bourgeoisie: 2. the chauvinistic racial movement of those elements of the black bourgeoisie who are interested in the isolation of the Negro population in order to secure for themselves the unhindered exploitation of Negro labour: 3. the racial movement of the Negroes can be a movement of the Negro workers and urban poor of the North, who are considerably more exploited than the white workers and also of the Negro agricultural labourers and Negro peasants of the South who are exploited by capitalist landlords. They are struggling for equal conditions of labour with the white brothers of their class, for full political and social equality between white and Negro workers. The class struggle is an attack upon imperialist super-profits. The racial movement is therefore a revolutionary anti-imperialist struggle, a struggle insolubly tied up with the revolutionary struggle of the poor peasantry and workers against capitalist exploitation.

This question is related to the general question of the Negroes throughout the world. In South Africa we have the question of a nationalist movement, the development of class contradictions between the middle and petty-bourgeois elements. In South Africa we have the question of whether we can lead the peasant revolution. In Haiti there is national aspiration. This question of nationalism needs the full attention of the Comintern in order that we can lay down a thorough theoretical basis for our future work in regard to the oppressed peoples and the Negro peoples in general.

Finally, we come to the third point and that is in reference to our practical programme in connection with our Negro work and our colonial work. I want to touch upon some aspects of the Negro question in regard to the approaching world war.

In the last war 2,290,000 Negroes were registered for military service by the United States, of whom 458,000 were examined for military service. Of this number 380,000 were inducted into full military service of the United States army. Of this number 200,000 served in France. At the present time the United States, in her feverish preparation for war, is not overlooking the Negro as a combatant troop as well as non-combatant soldiers. Two regiments of state militia have been federalised into the regular army and are being constantly trained. The National Defence Act of 1920 provided for the organisation of the Military Guards to train Negroes in peace times. This organisation is similar to The Minute Men, provided for by the same Act, an anti-labour organisation headed by General Dawes. Under the pressure of petty-bourgeois intellectual Negroes, Negro students are being sent to West Point, the military academy of the United States army.

France controls a colonial population of 60 million colonials in Africa. 845,000 colonials served in France in the last war; 535,000 were soldiers and 310,000 were labour contingents. The peace footing of the French army at the present time is 660,000, of whom 189,000 are colonial troops. In ten years time (estimated from 1924), France plans to have 400,000 trained colonial troops and 450,000 more ready to be trained.

England did not have as many colonial troops in the last war as France, but the troops of West Africa conquered German West Africa for England and held the Turks in check. At the present time England offers her greatest object lesson in the field of black labour.

Anglo-American rivalry throws up the possibility of black troops of these two nations being thrown against each other in the defence of “their” country. But more than this; it is not unlikely that in the event of the next war the scene of battle will shift to different parts of the world and even centre in Africa.

There is another grouping: the imperialist world against the U.S.S.R. In this alignment the imperialists intend to use if, possible, the Negro colonial troops as was done during the civil war in Russia in 1920, 21 and 22, in which France and England used black troops against the Red Army.

We must turn our faces to the colonies and prepare the colonial troops to turn their guns upon their oppressor, to fight for their liberation from imperialist exploitation and oppression. The various Parties, the French, British, American, Belgian, South African should now begin plans to turn the resentment of the Negro troops against their oppressors.

Now in regard to our practical work, we must begin to organise trade unions among the Negro peoples of the world. There has been set up at the Profintern an International Labour Bureau of Negro workers for the purpose of unifying the Negro workers and the white workers throughout the world. Where possible, to organise trade unions of white and coloured workers, and to organise coloured unions separately where this is not possible. This bureau will also issue bulletins, pamphlets and literature with the idea of centralising and consolidating and. bringing together the proletariat of the whole world, against the imperialist oppression and against a world war against the U.S.S.R.

Comrade JONES (U.S.A.):

Comrades, the draft theses on the colonial question are by far the most thorough theses in point of detail that we have had up to now on this question.

We see from the discussion so far that there is a considerable amount of disagreement with some of the points in the theses, particularly on India and China.

From the point of view of revolutionary activity at present China and India are the most important colonies to be considered. But we must not overlook the world significance of the Negro question, which in the past has not been given sufficient attention by the Comintern.

At the Fourth and Fifth Congresses of the Comintern, there was some discussion on the necessity of the creation of a Western Colonial Bureau, dealing with the Negro question. It seems that as far as actual work is concerned, the Bureau has done very little, and nobody knows what became of this Bureau afterwards. We also find in the archives much dusty material on this question that has never been read by anybody.

Comrade Kuusinen remarked that at present there is very little revolutionary activity in the continent of Africa among

the Negroes. This is true, but here can be much more revolutionary activity on this continent provided we paid a little more attention to the various movements that are in existence on this continent. I have in mind Portuguese East Africa. There is a revolutionary movement under the leadership of Communists and they wrote to the American Negro Labour Congress asking to be put in touch with the Comintern, and when this was mentioned to the Comintern, we understand that they had never heard anything of this movement and had no connections at all with these comrades. And I think it is necessary to get more contact with these various revolutionary movements that exist on that continent.

We organised here at the Congress, a small sub-committee of the Anglo-American Secretariat which dealt with the Negro question in America. This Commission has done a considerable amount of work, which of course is by no means complete, but the first steps were made for a real investigation of this question. In this commission there arose some sharp differences as to the character of the Negro movement in the United States. One point of view is that these Negroes are a racial minority but are developing some characteristics of a national minority and that in the future they will have to be considered as a national minority. The other point of view is that these Negroes are a racial minority and are not developing any characteristics of a national minority and that the basis that would develop these characteristics is rapidly dis- appearing, that there exists no national entity as such among the American Negroes.

We have a sharp differentiation in classes among the American Negroes, particularly after the world war and this class differentiation tends to prevent a development of any national characteristics as such. We find the Negro bourgeoisie are becoming more and more an integral part of the whole of the American bourgeoisie and are completely separated as far as class interests are concerned from the majority of the Negro toilers. The historical development of the American Negro has tended to create in him the desire to be considered a part of the American nation. There are no tendencies to become a separate national minority within the American nation. I have material on this which will be submitted to the Colonial Commission, in support of our disagreement, together with the theses drawn up by the Negro Commission.

This is a very important question and deserves careful study before any definite steps are taken in drawing up a programme or advancing slogans for our work among the American Negroes. Some comrades consider it necessary at this moment to launch the slogan of self-determination for the American Negroes; to advocate an independent Soviet Socialist Republic in America for Negroes. There is no objection on our part on the principle of a Soviet Republic for Negroes in America. The point we are concerned with here is how to organise these Negroes at present on the basis of their everyday needs for the revolution. The question before the Negroes today is not what will be done with them after the revolution, but what measures are we going to take to alleviate their present condition in America.

We have to adopt a programme that will take care of their immediate needs, of course keeping in mind the necessity for organising the revolution.

A comrade remarked that it was necessary for us to establish a new line of work among the Negroes, to adopt a new programme. It is not so much the question of a new programme but of carrying out the programme that was adopted by the IV. and V. Congresses on this question. Up till now nothing has been done. The central slogan around which we can rally the Negro masses is the slogan of social equality. And the reason why we have not organised the Negroes in America and why we have such a small number of Negroes in our Party, is because we have not fought consistently for this principle. And this is due to the fact that we have white chauvinism in our Party. Therefore, before we should attempt to launch a slogan of self-determination for the American Negroes as a central slogan, we should give more study to this question. A Bureau should be set up in the Comintern dealing specifically with the Negro problem to analyse and study the objective situation in the various countries where there are Negroes and from this study formulate our programme.

Comrade WOLFE (U.S.A.):

Comrades, I want to say a word about the thesis in general. I have seen in it certain formulations which need alteration or correction, amendments, and so on. I want to say that those who reject them fundamentally have a fundamentally wrong approach to the colonial question. I consider the theses unquestionably a most valuable contribution to the work of the Communist International.

The primary merit of this thesis is its effort, and in general its success, in picturing the complicated variety in the process of colonial development and colonial revolutionary movements in the various portions of the world. The theses represent a passing over from the general formula with which the Communist International has largely had to content itself since the basic work of Lenin at the Second Congress, to its application in detail to the concrete and the greatly complicated phenomenon of the colonial picture. In addition the theses utilise the rich experiences of some eight years of struggles in the various colonial and semi-colonial fields.

Other merits of the theses are the attempts to define the colonial regime as to its economic and political characteristics, classification of the colonies according to the degree of development of class relationship. The distinction is made clear between the driving forces of the various revolutions and their political content.

Comrades, in confusion of the distinction between the class driving forces of a revolution and the political content of a revolution, in confusion between bourgeois democratic and Socialist revolution, in confusion on the question of phases in a colonial revolution, in confusion on these three fundamental lines lies the basis for the Trotskyist conception of the colonial question. The theses greatly clarify these important points.

I turn now to the question of “decolonisation”…

1. There exists a general tendency of capitalism to draw the entire world into the train of capitalist production, to destroy the earlier forms of economy and to introduce capitalist conditions throughout the world.

2. This tendency is undoubtedly strengthened by the export of capital.

3. To bring the whole world into the orbit of the capitalist system, however, does not necessarily mean that all sections of it need be industrialised. Capitalist market relations, plus imperialist rule, plus capitalist agricultural relations would also satisfy this tendency. The basic in industrialisation in a country is the development of those industries which produce means of production.

4. In addition to this basic general tendency towards the development of capitalism throughout the world, imperialism expresses a direct counter-tendency, namely, to intensify the parasitic exploitation and the restrictions upon the development of the backward portions of the world.

5. There have been two periods in the development of modern economy when this restrictive tendency was dominant. These periods were the period of early monopoly out of which modern capitalism grew, the period of “mercantilist” policy in regard to the colonies; and then the period of monopoly on the basis of finance capital, the export of capital and trustification.

6. While the industrialisation and the production of capita- list conditions in the backward nations is growing in an absolute sense of quantity, the parasitic restrictive aspect of imperialism is the dominant one.

7. The so-called decolonisation tendency of capitalism is to such an extent counter-acted by the parasitic restrictive tendency of imperialism that we even witness a tendency towards recolonisation or better, towards colonisation in the sense of reducing previously independent regions of the world to the status of semi-colonies. We have had in the post-war period, the growth of a whole series of such new semi-colonies where there was no question of colonial status before.

8. Of the two tendencies, that is, of the tendency to further the industrial development of the backward portions of the world and the counter-tendency to hinder, restrict, and prevent this industrial development, the latter is undoubtedly dominant. The fundamental in this period of finance capital and capital export, is not as Comrades Rothstein, Bennet and some of the other speakers said, the industrialisation tendency but the parasitic exploitation tendency of the countries which export capital. To miss this, comrades, is to miss the fundamentally parasitic role of imperialism. To hold the theory that the dominant tendency of imperialism is to develop modern production in the backward portions of the world, would lead objectively towards an underestimation of the oppressive reactionary role of imperialism, of the necessity of and the sharp explosive force of the struggle against it. Carried to its logical conclusion, it leads objectively to an opportunist and even an unconscious apologetic line in the question of the role and character of imperialism.

9. The contradiction between these two tendencies is one expression of the antagonism between metropolis and colony.

10. This antagonism, together with the class struggle within the various countries, together with the antagonisms between the imperialist powers and the Soviet Union, will lead to the destruction of imperialism long before this ideally conceived industrialisation of the world is completed or has progressed basically far. Only Socialism will complete the task but on a new basis of division of labour and planned economy on a world scale.

I want to turn now to Latin America. Certainly here also both tendencies are observable. But, again there can be no question as to which is dominant.

It is perfectly true that the United States, in certain countries of Latin America has found it necessary to overthrow certain reactionary forces. The reason is a historical one, namely, that Great Britain was in those countries first, picked in advance the best natural allies for imperialism in those countries, namely, the land owners and reactionary Catholic church. When the United States came upon the field to challenge Britain’s privileged position the U.S. was faced with the accomplished fact of the union between landowners and Catholic reactionaries with British imperialism, and in order to break ground for the forward march of the dollar it was necessary to further certain revolutionary forces in those countries.

However, just as soon as Britain’s puppet governments were overthrown, then the United States tried to stem the tide of the revolutionary development which it had helped to set loose. In those countries in Latin America, where the United States can take its pick, it links up with the semi-feudal, catholic landowning reaction and all the most backward class forces in the country. Thus, we find that the United States sets up a Fascist dictatorship, autocracies of the most brutal sort, in such countries as Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Colombia, Peru, Bolivia, and Chile.

So far as Liberia is concerned this “progressive” American imperialism is attempting to go back to a system of chain-gang, chattel slavery.

The situation in Latin America presents us with a whole series of new forms of semi-colonies of various grades and kinds, most of them maintaining their formal independence while the power of the United States grows greater and greater.

American imperialism has developed many forms of intervention. We can distinguish the following:

1. Military intervention, primarily in Mexico and the Caribbean countries. In those countries we have witnessed no less than 30 military interventions in a period of a quarter of a century.

2. Customs control. The Orient is not the only portion of the world where the customs of so-called sovereign countries are controlled by imperialism.

3. Direct fiscal control of bank appointees who are nominated by the President of the United States and formally approved by the puppet governments.

4. Military advisers.

5. The financing of “revolutions” and financing of reactionary dictatorships.

The general progress of American domination is from North to South, from near to far, from the Canal to the Straits of Magellan. Of course, it is not a regular march; certain countries were temporarily overlooked in order to make the jump into Chile for the copper and other mineral wealth there.

This march involves not only a struggle with the peoples of Latin America but also a struggle with British imperialism. The United States has invested in Latin America at the present time something like 5,200,000,000 dollars. If we add Canada we find that the United States has invested in the New World something over 8000 millions, out of a total of 13,000 millions which is invested in the world as a whole, exclusive of the war debts.

To date the United States has invested in Latin America almost an identically equal amount to Great Britain. You can calculate both of them in round figures at about 5000 million dollars, but before the war Great Britain already had 5000 million dollars invested in Latin America, and has today only 5,200,000,000 dollars, whereas the United States before the war had only 2,200,000,000 dollars and has equalised with Great-Britain now.

I want to underscore the importance of Latin America in the scheme of economy of the United States, and also its importance in the coming war period. Venezuela today with its oil resources scarcely touched is the third biggest producer of oil in the whole world; the first being the home territory of the United States. The Soviet Union is the second. Mexico is the fourth. Colombia and Peru have scarcely been opened up and are rich in reserves of oil. North Argentine and a section of Bolivia also show oil deposits. Metals are found in rich abundance and in the forms easy to extract. Raw materials of importance in making munitions are potassium and nitrates. There is rubber and, of course, agricultural products.

The Latin American revolutions belong to the bourgeois democratic revolutions. They represent a close fusion of revolutionary movements, primarily agrarian, with the struggles against American imperialism. However, the basic driving force in these revolutions is not the bourgeoisie, but the workers and peasants. This explains the vague socialistic aspirations which are in the hands of foreign capital, as are the banks, means of explains the Socialist phraseology, the radical gestures of the petty bourgeois governments that take advantage of these revolutionary forces for their own purposes.

During the electoral campaign of Calles and Angel Flores, for the Presidency of Mexico, Flores who represented the land-owning catholic reaction with the support of British capital, posted all over the country a placard with his picture and the words, “I am a Socialist and Revolutionary”. You can imagine what revolutionary phrases the “Socialist” Calles used if that was the character of the propaganda of the reaction.

We have in Latin America, for example, such dangerous careerists as Haya de la Torre of Peru who came to Moscow, who attended the Fifth Congress of the Comintern as a fraternal delegate, who came to the Third Congress of the Profintern as a regular delegate, and who has attempted to cover with the mantle of Communism an essentially non-Communist movement.

A few remarks as to class forces in Latin America:

a) We must not, in the first place, forget the great weakness of the national bourgeoisie in most of the Latin American countries. All important industries in most of these countries are in the hands of foreign capital, as are the banks, means of communication, etc. Thus, in Mexico, in the field of petroleum, the investment of native Mexican capital comes ninth on the list and even Cuban capital has more money invested in Mexican petroleum than have native Mexicans. This weakness of the native bourgeoisie helps to account for the greater role played by the petty bourgeoisie in Latin American revolutionary movements.

b) We must note the peculiar character of certain sections of the Latin American petty bourgeoisie. Intellectuals who are partially declassed, play an important role out of all proportion to their numbers in the movements of Latin America.

There are two basic reasons for the existence of discontent among the intelligentsia of Latin America. One is that foreign imperialism in general, and American in particular, tends to maintain in power for indefinite periods autocratic governments, until these degenerate into cliques of superannuated bureaucrats who leave no room for the young intellectuals being turned out by the universities to find a career in the important sphere of government. This was one of the driving forces which made the student body and the young intellectuals of Mexico virtually unanimous in their opposition to Diaz and his group after they had been in power for thirty years. A similar situation exists in countries like Venezuela, Peru, etc. Secondly, there is the tendency of American capitalist enterprises to employ as technicians, engineers, overseers, etc., Americans so that the only other field that night be open to intellectuals is thereby closed to them by imperialism. They have only one field of activity, namely, opposition politics and anti-imperialist politics. and into this they tend to enter. They represent, however, a dangerous force combining with the usual vacillating characteristics of the petty bourgeoisie and intelligentsia, a peculiar susceptibility to both open and indirect bribery, being readily satisfied by a “share” in the government.

c) The proletariat in the Latin American countries, with the exception of the most developed of them, is extremely weak. This is a reflection of the weakness of the industrial development in general. Also, even where there is a proletariat developing it is still lacking in experience, organisations, technique and discipline, due to the newness of the proletariat as a class. It is closely linked up with the peasantry, often made up of only recently “deruralised” peasants. This infiltrates the proletariat with peasant ideology and makes popular a sort of “narodnikism”.

d) As to the peasantry, it presents some peculiar features in many of the Latin American countries which makes it necessary to distinguish sharply between it and the European peasantry. The peasant in many Latin American countries is not a landowner of even the smallest parcel of land, he is a former joint owner of communal lands. The process of creating large estates, of dispossessing the peasant Indian communes, the process of enclosures has removed him from the land, pauperised him and made him into an agrarian worker. However, he retains the traditions of having been a possessor of land and the ambition of recovering the lands taken from him, or his immediate forefathers. Often he does not even demand private property in land, but demands that the communal lands be restored to the entire village unit or tribal unit that formerly possessed them.

e) There are whole sections of inland countries in Latin America where Spanish is not the language of the people, where there are still vast Indian tribes with strong survivals of tribal organisation. These Indian tribes speak their own language, retain strong vestiges of primitive Communism in their tradition and their economy and in some cases have a powerful tradition of former tribal glory. (Incas, Aztecs, Mayas, etc.) They view Europeans and even mixed white and Indian natives of the coastal and more industrialised regions of the country with suspicion and even aversion and can rarely be led by those who cannot speak their own tribal language. The Parties of Latin America in those countries must work out a whole series of special measures to meet these problems, measures involving such matters as self-determination for the indigenous races, special propaganda in their own languages, special efforts to win leading elements among them, special educational activities for those Communists who are of Indian origin and who speak the Indian dialect so that they can go back into the inner regions of the country and organise the indigenous elements.

The history of the last generation in these Latin American countries where compact indigenous tribes exist, is characterised by a whole series of Indian uprisings, sometimes against foreign imperialist oppressors, sometimes against the landowners, sometimes against the native state bureaucracy generally a fusion of these three revolutionary moments. These uprisings constitute the greatest reserve of revolutionary energy that exists in Latin America which reserve is only very imperfectly connected with the proletarian and agrarian peasant movements of the rest of the countries.

f) Emphasis must be laid on the lack of bourgeois democratic and parliamentary traditions in Latin American political life and lack of such traditions and illusions among the masses. The weakness and often times virtual non-existence of the native bourgeoisie is of course the basic explanation of this. The petty bourgeoisie makes up the state apparatus and often times the officer ship of the armies. A struggle for control of the treasury is quite literally an important force in the conflicts between the different so-called parties in Latin American life.

g) As to the rival imperialisms the conflicts between them often result in liberating revolutionary forces in a country where they are about equally balanced. Each of them supports contrary elements, and if one of them is tied up with the reaction, the other one has to tie up with the progressive elements. The result is a continuous see-saw manifested in Mexico since the discovery of oil there. This has tended to liberate revolutionary forces in the country. We may look for a similar situation now in a country like Venezuela where oil has been discovered in such quantities and where British and American capital are in pretty even balance.

h) The leaders of the American Federation of Labour, Green and Woll and their henchmen, Morones, Iglesias, Cariato Vargas, etc., with their Monroe Doctrine of Labour and their Pan-American Federation of Labour seek to paralyse the fighting will of the Latin American masses, and pave the way for the new conquest of the continent. The American and Latin American parties must set up the closest union of the working class organisations of Latin America with each other, with the Left wing of the American labour movement and with the R.I.L.U.) I think the Congress must categorically reject the proposal for the founding of Workers’ and Peasants’ Parties in the Latin American countries.

Our primary task in Latin America is to establish Communist Parties, build them strong and make their lines of demarcation clear. They must penetrate the mass movements of the workers and peasants and lead these movements. Particularly in view of the weakness of the parties, the political backwardness of the masses, the lack of parliamentary tradition and the excessively big role played by the petty bourgeoisie state bureaucracy and the petty bourgeois professional politicians in Latin America, there is the danger that such elements will get control of the workers’ and peasants’ party. The correct form for Latin America today is the worker-peasant bloc with leadership by a steadily developing Communist Party.

j) In the various struggles against imperialism and against internal reaction in the various countries, the workers and peasants must enter as a separate force. The Communist Party must make clear its own programme at every stage, must criticise at every stage the elements with which at times it must cooperate; must struggle consistently for the hegemony in those movements. At the same time we must pay special attention to the organisational form that the struggle manifests. For example, when elements of a still revolutionary character seek the support of the peasants and workers of Latin America, we must put down as one of the minimum organisational conditions the right of those workers and peasants to separate armed detachments under their own leadership, with their own programme, and maintaining the status of guerilla forces in the general struggles that take place. This tactic has been applied with some success in Mexico, and as a result, whole sections of the peasantry are armed today, and in spite of the repeated efforts to disarm them, they retain their arms. There is a new wave of resistance against American imperialism; a new development of revolutionary forces in the agrarian revolution, and all the chases of the revolutionary movement in Latin America. I mention only a few instances: the long struggle in Mexico, the revolutionary struggle in Ecuador, uprisings in Brazil, in Colombia, in Peru, in Venezuela, in Bolivia, in Paraguay, in Northern Argentina; the sharpening struggle in Chile, which has only temporarily been defeated by the establishment of a brutal military Fascist dictatorship. And above all, the heroic resistance that has been manifested by such little countries as San Domingo, Haiti and Nicaragua and the other Central American countries to the aggression of the United States. Costa Rica has been quiet for a while, but we find here in an issue of a Costa Rican paper of May 18, 1928 that a motion of interpellation to the Secretary of Foreign relations as to why they are not recognising the Soviet Union, and a demand that the United States blockade be broken in this respect, was carried by the Chamber of Deputies. This means that there are stirrings among the masses, or these petty-bourgeois politicians would never attempt to frame such a demand.

The outstanding example of the new strength of the resistance of Latin America to American imperialism is the struggle in Nicaragua. This is the first time that Nicaragua, or any of the small Central American countries, has. been able to put up so brave a resistance for so long a period. For a year and a half, in one form or another, the forces of national liberation in that diminutive country have been holding at bay the marines of the United States and carrying on, with more or less success, incredibly heroic guerilla warfare. The United States has still not succeeded in winning this war in Nicaragua. Never before has such a struggle awakened so much echo in the rest of Latin America and gone so far towards unifying the revolutionary and anti-imperialist forces in Latin America for a common struggle.

In the face of the dominant power of American imperialism in the world today, Latin America assumes more importance than ever; in fact, it moves up to the first rank among the vital questions concerning the entire Communist International. The United States and the Soviet Union represent the two poles of the earth today. The whole Comintern must turn its attention to this natural enemy of American imperialism, this natural ally of the proletariat of the world. the revolutionary movements of the Latin American peoples. At the 5th Congress Latin America was represented by one Party and two League delegates for all of these numerous countries put together. The large representation at the 6th Congress is an evidence that the Comintern has already turned its eyes in that direction, and an evidence also of the rapid development of class relationships in Latin America. But the entire Comintern, and particularly the American section of the Comintern, must multiply by many times its attention and its aid to the Communist Parties and the revolutionary movements of Latin America.

The Latin American countries are still in the so-called Latin Secretariat. Because our apparatus unfortunately is built on a basis of language, in place of common political problems. I think that some reorganisation must come after this Congress in which common political problems become the basis of grouping, and not common language.

Finally, I want to say that as far as the question of “Latin-Americanism”, which has been raised in the discussion here, is concerned, we cannot slavishly accept the general proposals for Latin American unity which are made by the petty bourgeois intellectuals of Latin America. The proposal for a union of all the existing governments and countries as at present constituted in Latin America is a fundamentally false and reactionary proposal, because they include whole series of puppet governments of American imperialism, and some governments which are still puppets of British imperialism. We must raise the slogan of the union of the revolutionary forces, the workers and peasants movements, of Latin American with the revolutionary workers of the United States; and we must add to that the slogan of the Union of Soviet Workers and Peasant Republics of Latin America for a common defence against American imperialism, and for a common federation in a Soviet Union.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecorr” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecorr’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecorr, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n74-oct-25-1928-inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n76-oct-30-1928-inprecor-op.pdf

PDF of issue 3: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1928/v08n78-nov-08-1928-inprecor-op.pdf